Many of the world's early civilizations had an interest in global navigation. There are stories of ancient Egyptian attempts to sail around Africa; Chinese voyagers explored much of the coastline of Asia, India, and eastern Africa; most impressive, perhaps, in terms of results obtained from limited resources was the colonization of the Pacific by Polynesian sailors. However, it was the great European seafarers of the 15th to 18th centuries who began a systematic discovery of the earth's geographical secrets. Names such as Columbus, Magellan, Tasman and Drake are as well known today as they were in the lifetimes of the people who carried them.

If the maritime nations of Europe had pooled the knowledge gained by their navigators, the 18th century map of the world would have been much more complete than it was. But since "knowledge itself is power", much of what each nation had discovered through its voyages of discovery remained hidden from its political and economic rivals. In time, exploration became a kind of arms race, with each new land, or each new navigational technique, the equivalent of a secret weapon.

By the 18th century, many of the areas of influence had already been drawn. South and Central America was largely a Spanish domain. North America belonged to the British and French. European supremacy in southern and south-east Asia was a contentious issue, with the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, French and British all vying for supremacy.

The attention of British and French explorers had also begun turning to the Pacific. The British, in fact, had sent a number of missions into the Pacific as early as Drake's voyage around the world in 1578-80; but most of those had been raids on Spanish outposts and treasure ships. By the second half of the 18th century, the hunger for knowledge was beginning to outweigh greed as a motive for exploration, and the "Golden Age" of Pacific exploration had begun.

The British were first (in 1764) with the ships Dolphin and Tamar under the command of Commodore John Byron (grandfather of the poet Lord Byron). This voyage was not particularly successful, but it was followed in August 1766 by a second expedition, led by Captain Samuel Wallis aboard Byron's ship Dolphin and Lieutenant Philip Carteret aboard the Swallow. The two vessels became separated while navigating Magellan Strait and never regained contact; each ship made its own way home. Dolphin returned to England in May 1768; Swallow, the slower vessel, made it back exactly one year later.

Wallis had been instructed to search for Terra Australis Incognita, the theoretical continent that was supposed to exist south of the equator in order to "balance" the large land masses in the northern hemisphere.

(Incidentally, Australia was not the great southern continent they had in mind. Geographers knew that "New Holland", as Australia was then called, existed, but it was considered too small to be the continent in question.)

Neither Wallis nor Carteret saw anything remotely like that fabled continent. They did, however, discover or rediscover a number of islands. For example, Wallis was the first European to discover Tahiti, a tropical paradise rich in food and populated by friendly inhabitants; and Carteret discovered Pitcairn Island, which was later made famous as a result of the Bounty mutiny.

The French were slower off the mark than the British, but, when their first expedition to the Pacific set out, it did so with most thorough preparation.

The first French expedition to the Pacific, comprising the vessels Boudeuse

and Etoile, set out in November 1766, very soon after Wallis left

Plymouth. It was commanded by Louis-Antoine de Bougainville and among

its members were a number of experts: the astronomer Véron, the botanist

Commerson, and the cartographer Romainville among them.

Bougainville's voyage was an outstanding success. The expedition discovered a wide variety of new botanical species, conducted a number of astronomical experiments, and made several important geographical discoveries. Bougainville also "discovered" Tahiti (less than a year after Wallis) and was even more impressed by that land and its people than Wallis had been.

After leaving Tahiti, Bougainville sailed west, encountering first Samoa, then Vanuatu. In fact, Bougainville came close to being the first European known to have explored the eastern coast of Australia, but about 150 kilometres east of the Australian mainland (and in latitude close to where Cooktown is today) he was blocked by the reef that now bears his name. Rather than risk the safety of his vessels in what we now know as the Great Barrier Reef, Bougainville turned north. He passed through the Solomon Islands, one of which also bears his name, and ultimately returned to France by way of Batavia and the Cape of Good Hope, arriving home in March 1769 to a hero's welcome.

In 1768 came the Endeavour expedition of Lieutenant James Cook.

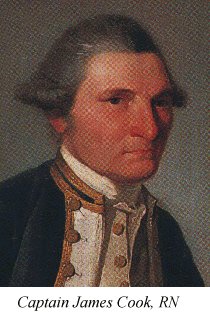

James Cook was born in 1728 at Marton (now Marton-in-Cleveland), in the North Riding of Yorkshire, with what we would call limited career options. Being the son of a farmer, he had no real prospect of advancement in the rigidly class-dominated culture that was British society in the 18th century. At the age of 17, he began work as a shopkeeper's apprentice.

But Cook had ambitions for a naval career. In 1746 he left his shopkeeper's position for sea-going employment with John Walker, a coal-shipping merchant of Whitby. He gained experience in coastal shipping, and then spent two years in the Baltic trade. In 1752 he was appointed mate of Walker's vessel Friendship, and in 1755 was offered command of the same vessel.

He turned down this offer, opting instead to enlist in the Royal Navy with the lowly rank of able seaman. Whatever Cook's reason for doing so – a sense of adventure, the hope of advancement, or even the promptings of patriotism – the change happened at a good time for both Cook and the Royal Navy. Cook's first posting, in June 1755, was to HMS Eagle, and within a month he was promoted to the rank of master's mate.

In 1756, the Seven Years' War broke out in Europe between

Prussia, Hanover and Great Britain on one side and France, Austria, Saxony,

Sweden and Russia on the other. While the other powers contended mainly

in Europe, the British and French used the opportunity to fight for control

of North America and India, which the British finally gained.

In 1756, the Seven Years' War broke out in Europe between

Prussia, Hanover and Great Britain on one side and France, Austria, Saxony,

Sweden and Russia on the other. While the other powers contended mainly

in Europe, the British and French used the opportunity to fight for control

of North America and India, which the British finally gained.

Cook attained the rank of master in 1757, and in 1758 sailed for Canada aboard HMS Pembroke to take part in naval operations in the St Lawrence River and in the British capture of Quebec.

It was in the St Lawrence that Cook undertook his initial training in surveying. In 1759 he transferred to HMS Northumberland. On that ship's return to England in 1762, Cook was commended so strongly for his work in pilotage and surveying that the new British Governor of Newfoundland asked that he once again be sent out to chart the waters around that colony. This was done, and Cook ended his tour of duty in late 1767 as commander of the schooner Grenville. (The Seven Years' war had officially ended in 1763.)

Among the skills that Cook developed during his tour of duty in the New World was that of astronomical observer, so much so that his description of an eclipse of the sun in 1766 brought him to the notice of the Royal Society.

The "Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge" was founded by King Charles II in 1660, with the aim of giving men interested in science the chance of meeting to discuss matters of mutual interest. Its membership over the centuries has included many eminent people, some of the more famous of them being Isaac Newton, Benjamin Franklin, Charles Darwin and Michael Faraday.

In the mid-18th century, two of the major topics of discussion within the Society were the possible existence of an undiscovered continent in the Earth's southern hemisphere and an impending astronomical event, the crossing (or transit) of Venus across the face of the sun. From a scientific point of view, the second of these was more significant. After all, no-one knew if a Great Southern Land actually existed or what it might contain; on the other hand, the transit of Venus would be a measurable physical event.

Only the two inner planets of the solar system – Mercury and Venus – can pass between the Earth and the sun. Transits of Mercury are relatively common, but quite difficult to observe without skill and the proper equipment: Mercury is a small planet, and far away. Observing a transit of Venus is easier, since Venus is larger and (during transits) closer to the Earth. However, transits of Venus are very rare, since Venus orbits the sun in a slightly different plane to the Earth; only five transits of Venus have so far been observed – in 1639, 1761, 1769, 1874, and 1882.

In November 1639, Jeremiah Horrocks, a British clergyman and astronomer, became the first recorded observer of a transit of Venus. Before 1761, he was still the only recorded observer of such a transit. Astronomers were adamant that he wouldn't be the only one after 1761.

It was in 1663 that James Gregory, a Scottish mathematician, suggested that a transit of Venus could be used to measure the distance from the Earth to the sun. The astronomer Edmund Halley went one better: in a paper published in 1716, he showed that parallax would cause observers in different parts of the world to obtain different measurements for the duration of the transit – differences that then could be used to measure the distance from the Earth to the sun.

A number of expeditions, mainly from France and Britain, viewed the 1761 transit (visible from Asia, northern Europe, the Indian Ocean and the East Indies), but with limited success. Of the two expeditions sent by the British Government at the request of the Royal Society, the one to Sumatra was attacked by the French and the second, to St Helena in the South Atlantic, was defeated by cloudy weather.

Undaunted, the astronomers intended to try again. As with the transit of 1761, British plans for viewing the transit of 1769 were mediated by the Royal Society, which asked King George III to authorize three more expeditions, including one aboard a Royal Navy vessel to Tahiti in the South Pacific.

The Royal Society's choice to command this expedition was Alexander Dalrymple, geographer and former employee of the English East India Company. Dalrymple was also a prominent believer in the existence of Terra Australis Incognita. Dalrymple wanted to take advantage of the South Pacific expedition to undertake further exploration, including another search for Terra Australis. This was a desire shared by the British Government; but unfortunately for Dalrymple, the Royal Navy refused to let anyone but a Navy officer command a Navy ship. Though the expedition would go ahead, Dalrymple would not be on it.

The Admiralty lost no time in organizing the expedition. (Indeed, there was little time to lose.) Its first request, in February 1768, was to the Navy Board, asking for a vessel suitable for a voyage of discovery in the South Seas. The Navy Board did not opt for a fast and graceful warship, but suggested instead a cat-built bark similar to the kind James Cook had sailed in as a civilian. On 29 March 1769 the Navy purchased the Earl of Pembroke, a cat-built Whitby collier built in 1764 and weighing 368 tons. The ship was immediately renamed His Majesty's Bark Endeavour and outfitted for her voyage of discovery. The outfitting was quite extensive, and included the addition of a lower deck and a number of cabins. The hulls of some earlier vessels used for exploration, notably the Dolphin that had taken Wallis to Tahiti, had been sheathed in copper to deter attack by shipworm. The Endeavour instead was covered with a false skin of light planking, and this sheathing was then filled with nails.

The ship was being fitted out. But who would command her? As we have seen, Alexander Dalrymple, the Royal Society's choice, had been rejected by the Admiralty. The commander of the expedition had to be a competent astronomer, a master navigator and surveyor, a naval officer, and preferably someone familiar with handling a Whitby collier.

Who else but James Cook?

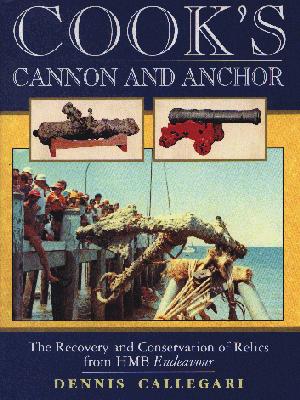

Cook was promoted to Lieutenant and appointed to command the Endeavour in May 1768. Under his command, the ship was fitted out with 10 cast iron cannon, 12 swivel guns, five anchors, three boats (longboat, pinnace and yawl), a number of scientific instruments, ammunition, and provisions and livestock. In short, enough food and supplies to last a complement of 94 men for 18 months.

Those who were to sail aboard the Endeavour numbered not only the officers, crew, servants and a squad of marines, but also several specialist passengers.

The passenger we know best was Joseph Banks, a very wealthy young man (born 1743) whose enthusiasm for natural science had already gained him a fellowship of the Royal Society. Banks was so keen to go along on the Endeavour voyage that he'd volunteered to pay for a staff of eight scientists and assistants to accompany him on the expedition. It was an expensive gesture, costing about 10 000 pounds, a considerable fortune in those days. Banks' retinue consisted of the botanist Dr Daniel Carl Solander, his assistant Herman Sporing, two artists (Sydney Parkinson and Alexander Buchan), and four servants.

The most important passenger (as far as the Admiralty and the Royal Society were concerned) was Charles Green, who would be the senior observer of the transit of Venus at Tahiti. Green was an experienced astronomer, having been an assistant to the astronomer-royal. He had just returned from a voyage to the West Indies, where he'd helped to test one of the new Harrison chronometers. (These chronometers would prove invaluable in Cook's later voyages, facilitating the calculation of longitudes. However, no chronometers were available for the Endeavour expedition; on this voyage, Green would have to make do with calculating longitudes by means of lunar differences, a still relatively new skill that he would soon impart to Cook and several of his crew.)

We know a lot about the voyage of the Endeavour. We have the ship's log, of course, and Cook's own journal of the expedition. Both Joseph Banks and his illustrator Sydney Parkinson kept journals, as did the astronomer Charles Green. We also have copies of full or partial journals from no less than 11 members of the crew.

From those records, we know that His Majesty's Bark Endeavour, with her crew of 94, sailed from Plymouth in the south of England at 2.00 p.m. on 25 August 1768. Along with her complement of men, equipment and supplies, she carried two sets of instructions.

The first set – for general consumption – instructed Cook to sail to Tahiti in order to observe the transit of Venus. The second, secret, set of instructions instructed him to sail south from Tahiti in search of Terra Australis. Cook was to take his vessel as far as 40 degrees south latitude and then proceed in a westerly direction, searching for the unknown continent, until he met the eastern coast of New Zealand, which had been discovered by Abel Tasman in 1642. If Cook failed to discover the supposed continent, he was then to explore as much of New Zealand as he could, and to observe with accuracy any other islands he might discover. Nowhere in his orders was Cook specifically instructed to explore the land of New Holland.

(In fact, the secrecy of Cook's instructions was compromised even before the Endeavour set sail. The London Gazette of Friday 19 August 1768 carried an article headed "Secret Voyage" and subtitled "Search for unknown continent south of the Equator", in which the contents of Cook's secret orders were revealed. The wording of the article leaves little doubt that its author had already seen a copy of the orders.)

If one purpose of the voyage was secret, the Endeavour's first few ports of call were not. Madeira was first, and then Rio de Janeiro, where Cook had difficulty in convincing the authorities that his vessel was a ship of the Royal Navy and not an illegal merchant vessel. After Rio, the Endeavour anchored off the eastern coast of Tierra del Fuego, where Joseph Banks and his naturalists went ashore to collect plant specimens, and at the same time ran foul of the local weather, which took the lives of two of Banks' servants.

The Endeavour reached Tahiti on 13 April 1769, giving Cook seven weeks in which to prepare for the transit of Venus. It also gave him time to explore Tahiti further, and gave the naturalists ample time to collect more botanical specimens. Despite the minor set-back of having its astronomical quadrant temporarily stolen by Tahitians, the expedition's astronomical observations went as planned, and Cook, Green and Solander duly observed the transit on 3 June 1769. (Because of observational difficulties, the data obtained by Cook – and by other observers around the world – did not in the end produce a value for the distance between the Earth and the Sun as exact as had been hoped; but this was not to be known until the data were compiled in Europe in 1771.)

While in Tahiti, the members of the Endeavour expedition also carried out with diligence the other aspects of their mission to Tahiti: to cultivate a friendship with the Tahitian natives, to trade with them, and to survey the island thoroughly.

By mid-July, with the Tahitian leg of the expedition completed, the Endeavour was ready for the next part of her voyage: to search for the unknown southern continent. This Cook did, pausing only to survey a number of islands north-west of Tahiti, which he named the Society Islands. On one of these islands, "Ulietea" (Raiatea), the Endeavour took on some stone ballast.

The course that Cook had been instructed to take should have intersected the coastline of Dalrymple's supposed southern continent at some point. It did not. Instead, on 7 October 1769, the crew of the Endeavour sighted the east coast of New Zealand. The Endeavour spent nearly six months circumnavigating the North and South Islands of New Zealand. During that time, Cook produced a detailed map of their coastlines, Banks and Solander collected 400 species of plants, and the crew of the Endeavour had a number of encounters with the local Maoris – some friendly, some decidedly not.

Cook's survey of New Zealand completed the last of the tasks the Admiralty had set him. He had observed the transit of Venus; he had searched for (though not found) a great southern continent; he had explored the coast of New Zealand. The Endeavour, however, was still half a world from home, and Cook had to decide what to do next. The extent of what he could do depended on the condition of his ship and of his men. He had a ship that was beginning to show the strain of a two-year voyage; and, though he had lost few men to disease or accident, the living conditions aboard the Endeavour were beginning to deteriorate and food was getting short.

Ideally, Cook would have preferred to go home eastwards, retracing his path around Cape Horn but at a higher latitude, thereby establishing conclusively whether a great southern continent existed or not; but let's hear him in his own words, from his own journal. The date is Saturday, 31 March 1770.

". . . being now resolved to quit this country [New Zealand] altogether and to bend my thoughts towards returning home by such a rout as might conduce most to the advantage of the service I am upon, I consulted with the officers upon the most eligible way of puting this in execution. To return by the way of Cape Horn [South America] was what I most wish'd because by this rout we should have been able to prove the existence or non existence of a Southern Continent which yet remains doubtfull; but in order to ascertain this we must have kept in a high latitude in the very depth of winter but the condition of the ship in every respect was not thought sufficient for such an undertaking. For the same reason the thoughts of proceeding directly to the Cape of Good Hope [South Africa] was laid a side especialy as no discovery of any moment could be hoped for in that rout. It was therefore resolved to return by way of the East Indies by the following rout: upon leaving this coast to steer to the westward untill we fall in with the East Coast of New Holland and than to follow the deriction of that Coast to the northward or what other direction it may take untill we arrive at its northern extremity, and if this should be found impractical than to endeavour to fall in with the lands or Islands discover'd by Quiros. "

(The Portuguese navigator Pedro Fernández de Quirós, employed by the Spanish, discovered the islands we call Vanuatu in 1606.)

Cook was not satisfied with merely obeying the orders laid out in his instructions. The Admiralty had gone to considerable expense to outfit the Endeavour expedition, and Cook was not about to be accused of doing less than he was able to. He judged that a survey of the hitherto unknown east coast of New Holland (whose northern, western and southern coasts had already been visited by sailors such as Jansz, Hartog, Tasman and Dampier) was within the capabilities of his vessel. The Endeavour set sail for Van Diemen's Land (which Cook hoped was the south-eastern tip of New Holland) but southerly gales drove the vessel north. Lieutenant Hicks, Cook's second-in-command, was the first aboard the Endeavour to sight the mainland of New Holland on 19 April 1770.

The Endeavour did not make landfall there, but turned north instead. Cook made his first landing in "New Holland" ten days later at Kurnell in Botany Bay. The Endeavour remained at Botany Bay for a week before once again sailing northwards along the continent and making two more landings, at Bustard Bay and Thirsty Sound on the coast of what is now Queensland.

By then, Cook had already begun to encounter the greatest hazard that the Endeavour would face on its three-year voyage – the Great Barrier Reef.

Growing mainly in shallow waters, coral reefs harbour a complex ecosystem that comprises not only the coral polyps themselves (which create the reef in the first place) but also algae, fish, molluscs and many other marine animals and plants.

The Great Barrier Reef, situated off the eastern coast of Australia, is the world's largest coral reef system, nearly 2000 kilometres in length. It stretches from the Tropic of Capricorn in the south to Torres Strait in the north, and consists of numerous islands, reefs and channels. The Reef is a fascinating place for the marine biologist; but to Cook it was to prove a source of anxiety: he would have to keep the Endeavour from running aground on one of the Reef's innumerable shoals.

As we have seen earlier in this chapter, it was the outer fringes of the Reef that had prevented Bougainville's expedition from sighting the eastern coast of New Holland only two years before. Cook had been luckier. In approaching the Reef from the south, he had by accident entered the Capricorn Channel between the Reef and the Australian mainland. Though no-one aboard the ship had realized the fact, by June 1770 the Endeavour was well within the Great Barrier Reef.

Cook ordered two more landings in early June – one on the mainland south of Rockingham Bay and one on Green Island – before he realized the hazard posed by the Reef. The date was June 11, 1770 (ship's time). The hazard took the form of several coral shoals and low islands (probably the Agincourt Reefs and Hope Islands); and it persuaded Cook to change course east-north-east away from the coast in order to avoid the danger of running aground.

But Cook's precautions were not enough, and, at 11 p.m. on that day, the Endeavour ran aground on an unseen reef.

Some experts find it surprising that Cook, rather than anchoring for the night, elected instead to keep the Endeavour sailing in what we know now to be treacherous waters. When he learned later of the grounding, Alexander Dalrymple, the man whom the Admiralty had rejected as leader of the Endeavour expedition, went so far as to accuse Cook of rash navigation. But hindsight often creates an illusion of clarity where none exists. Cook didn't know that the Endeavour had sailed into such an extensive reef system, and his journal for June 11 tells us that he was not unduly worried about reefs since he had "the advantage of a fine breeze of wind and a clear moonlight night". Moreover, the Endeavour seemed to be sailing into deeper, safer, waters.

Avoidable or not, the grounding of the Endeavour threatened imminent destruction for the ship and all her crew, and figures prominently in the journals of all involved. The most informative of these accounts are those of Cook, Joseph Banks, and the artist Sydney Parkinson.

Parkinson had been originally hired by Joseph Banks to

be the Endeavour's botanical artist, but after the death in Tahiti

of Alexander Buchan (the Endeavour's lanscape artist and portrait

painter) he took on all the burden of illustration for the expedition.

Parkinson was not a brilliant artist, but he was capable and hard-working,

and also a keen observer of the people and places visited by the Endeavour.

His journal contains perhaps the most personal eyewitness account of the

grounding.

Parkinson had been originally hired by Joseph Banks to

be the Endeavour's botanical artist, but after the death in Tahiti

of Alexander Buchan (the Endeavour's lanscape artist and portrait

painter) he took on all the burden of illustration for the expedition.

Parkinson was not a brilliant artist, but he was capable and hard-working,

and also a keen observer of the people and places visited by the Endeavour.

His journal contains perhaps the most personal eyewitness account of the

grounding.

The most informative technical account of the grounding comes from Cook's journal, though the captain understandably ignores matters not absolutely vital to the survival of the ship and her crew. This "local colour" was amply supplied by Joseph Banks.

Let's begin a description of the events of that night with an excerpt from Banks' journal.

"While we were at supper she went over a bank of 7 or 8 fathom water which she came upon very suddenly; this we concluded to be the tail of the Sholes we had seen at sunset and therefore went to bed in perfect security, but scarce were we warm in our beds when we were calld up with the alarming news of the ship being fast ashore upon a rock, which she in a few moments convinced us of by beating very violently against the rocks. "According to an account published later, the shock of contact brought Cook above deck clad only in his drawers, but giving orders coolly and precisely. Sydney Parkinson gives a good account of his own frame of mind during the grounding.

"About eleven, the ship struck upon the rocks, and remained immoveable. We were, at this period, many thousand leagues from our native land, (which we had left upwards of two years,) and on a barbarous coast, where, if the ship had been wrecked, and we had escaped the perils of the sea, we should have fallen into the rapacious hands of savages. Agitated and surprised as we were, we attempted every apparent eligible method to escape, if possible, from the brink of destruction. "Cook himself, as expected, gives most details of what steps were taken next.

"Emmidiately upon this we took in all our sails hoisted out the boats and sounded round the Ship, and found that we had got upon the SE edge of a reef of Coral rocks having in some places round the Ship 3 and 4 fathom water and in other places not quite as many feet, and about a Ships length from us on our starboard side (the ship laying with her head to the NE) were 8, 10 and 12 fathom."Cook ordered the yards and topmasts struck. The long boat was launched and anchors deployed in deep water to help drag the ship off the reef. But the Endeavour was stuck fast. The situation was made worse by the fact that the accident had happened nearly at high tide, so that, unless the ship could be refloated immediately, it would be stranded on the reef at least until the next high tide twelve hours later.

The crew's efforts were in vain: they were unable to refloat the ship, and so had to wait. Banks for one did not find it an easy wait, especially since there was a real chance that the grounding had started a serious leak. At first the ship heaved and shifted on the reef. . . .

"At this point she continued to beat very much so that we could hardly keep our legs upon the Quarter deck; by the light of the moon we could see her sheathing boards &c. floating thick round her; about 12 her false keel came away. "Cook realized that, since the ship had run aground at or near high tide, the only reliable way to refloat the Endeavour was to lighten the ship as much as possible before the next high tide. Parkinson tells us:

"On the 11th, early in the morning, we lightened the ship, by throwing overboard our ballast, fire-wood, some of our stores, our water casks, all our water, and six of our great guns; and set the pumps at work, at which every man on board assisted, the Captain, Mr. Banks, and all the officers, not excepted; relieving one another every quarter hour. "

Again the crew's efforts proved futile, as Cook testifies.

"At a 11 oClock in the AM being high-water as we thought we try'd to heave her off without success, she not being a float by a foot or more notwithstanding by this time we had thrown over board 40 or 50 Tun weight; as this was not found sufficient we continued to lighten her by every method we could think off. As the Tide fell the Ship began to make water as much as two Pumps could free. At Noon she lay with 3 or 4 Strakes heel to Starboard. "The first high tide had not given them the chance to refloat the vessel, and the Endeavour had begun to leak badly. As Cook admitted later in a letter to the president of the Royal Society:

"We had now no hope, but from the tide at Midnight, and this only founded on the generally received opinion amongst Seamen, that the night tide rises higher than the day tide . . . . "As it happens, this "old seaman's tale" is not generally true. It did however prove to be correct for that particular time and place. The crew of the Endeavour waited for the night tide. Cook tells us:

"At 9 oClock the Ship righted and the leak gaind upon the Pumps considerably. This was an alarming and I may say terrible Circumstance and threatend immidiate destruction to us as soon as the Ship was afloat. "Things were getting desperate, and Banks agreed with Cook's concerns.

"At night the tide almost floated her but she made water so fast that three pumps hard workd could but just keep her clear and the 4th absolutely refusd to deliver a drop of water. Now in my own opinion I intirely gave up the ship and packing up what I thought I might save prepard myself for the worst. . . . "Cook decided it was best to try to save the Endeavour rather than abandon ship.

"However I resolved to resk all and heave her off in case it was practical and accordingly turnd as many hands to the Capstan & windlass as could be spared from the Pumps and about 20' past 10 oClock the Ship floated and we hove her off into deep water having at this time about 3 feet 9 inches water in the hold. "Though the ship was still in a desperate state, battered by the reef and leaking badly, there was now some hope for saving the expedition. Banks:

"We now began again to have some hopes and to talk of getting the ship into some harbour as we could spare hands from the pumps to get up our anchors; one Bower however we cut away but got up the other and three small anchors far more valuable to us than the Bowers, as we were obligd immediately to warp her to windward that we might take advantage of the sea breeze to run in shore. "Both Cook and Banks mention the loss of the small bower anchor (the port bow anchor, which, despite its name, was the same size and weight as the best bower). In the circumstances, it was probably only a minor irritant for Cook. Parkinson says nothing about losing the anchor, but gives a parting comment about the cannon that had been thrown overboard.

"When we threw the guns overboard, we fixed buoys to them, intending, if we escaped, to have heaved them up again; but on attempting it, we found it was impracticable. "Cook was understandably much more worried about saving the ship itself; and his main problem was the expedition-threatening leak in the Endeavour's hull. Jonathan Monkhouse, one of Cook's midshipmen, suggested a way to at least control the leak – a technique called "fothering". Monkhouse had once seen it used on a voyage from Virginia to London, and Cook promptly put him in charge of applying his knowledge to the Endeavour. Cook reports:

"He took a lower studding sail, and having mixed together a large quantity of oakham and wool, chopped pretty small, he stitched it down in handfuls upon the sail, as lightly as possible, and over this he spread the dung of our sheep and other filth . . . . When the sail was thus prepared, it was hauled under the ship's bottom by ropes, which kept it extended, and when it came under the leak, the suction which carried in the water, carried in with it the oakham and wool from the surface of the sail, which in other parts the water was not sufficiently agitated to wash off. "The operation was a success, and the dangerous leak was much reduced. (Incidentally, oakum – Cook's "oakham" – is loosely twisted rope fibre that has been impregnated with tar and is used for caulking seams in wooden hulls.)

Saved from immediate destruction, the Endeavour now limped towards the coast. Cook wanted to find a convenient harbour in which to beach his ship and repair the damage. What he found, a few days later, was what we call the Endeavour River, where the town of Cooktown stands today. Cook sailed into Endeavour River on Sunday 17 June and beached his ship on the evening of the following Thursday. The next morning he inspected the damage done to his vessel, only then realizing how lucky he and the crew of the Endeavour had been, because

"one of the holes, which was big enough to have sunk us . . . was in great measure plugged up by a fragment of the rock, which . . . was left sticking in it. . . . "

Cook stayed at Endeavour

River for seven weeks, until repairs were completed and the weather turned

favourable. Typically, he used the enforced landing to best effect: he

and Green obtained the longitude of the Endeavour's position by

observing a satellite of Jupiter; Banks and Solander collected botanical

samples; the crew saw their first kangaroo (and Sydney Parkinson sketched

it).

Cook stayed at Endeavour

River for seven weeks, until repairs were completed and the weather turned

favourable. Typically, he used the enforced landing to best effect: he

and Green obtained the longitude of the Endeavour's position by

observing a satellite of Jupiter; Banks and Solander collected botanical

samples; the crew saw their first kangaroo (and Sydney Parkinson sketched

it).

On 4 August, Cook set sail again, once more trying to negotiate what he now knew to be a treacherous Great Barrier Reef. The Endeavour continued up the eastern coast of the continent (being nearly wrecked at least once more) and rounded Cape York on 21 August 1770.

Batavia (modern-day Jakarta), on the north-west coast of Java, was Cook's next port of call, a stop that was forced on him by the poor state of his ship. More than two years of exploration, hardship, and near-shipwreck meant that Endeavour needed extensive repairs in an established shipyard, which only Batavia was close enough to supply.

Until the Endeavour left Australian shores, the crew had had an unexpectedly easy time – at least as far as shipboard illness goes. None of the crew had died of scurvy or dysentery or one of the many other diseases that were common at the time. A couple of sailors had drowned early in the voyage. One had died after drinking an excess of rum. One had died of tuberculosis contracted before the voyage. One of the Endeavour's marines had committed suicide by jumping overboard.

In fact, the party worst hit by tragedy in the early part of the Endeavour voyage had been that of Joseph Banks. Two black servants he had brought with him had died of exposure during an ill-fated expedition in Tierra del Fuego. Alexander Buchan, one of his artists, had died at Tahiti, probably after an epileptic attack.

Ironically, the most dangerous part of the voyage took place when the Endeavour limped into Batavia, that far-flung outpost of the Dutch trading empire.

Unfortunately Batavia, as well as being an important trading post, also had a well deserved reputation as a pest-hole. The Dutch had captured and razed the town in 1619, and had re-built it in the likeness of towns back home, complete with canals. These canals soon became breeding grounds for mosquitoes and other carriers of disease; by the 18th century, Batavia had become one of the deadliest environments on earth: fifty thousand people were said to die there every year.

The Endeavour arrived at Batavia on 11 October 1770, and left on 26 December, repaired and re-provisioned. In the meantime, Cook had lost several men to disease – presumably malaria – including two Polynesians who had joined the ship at Tahiti.

The Endeavour sailed from Batavia with a crew of sick men. Her next destination was Cape Town in South Africa; but before she reached it on 15 March 1771, 23 more men would die, including Sydney Parkinson, the astronomer Charles Green, and the midshipman Jonathan Monkhouse.

After rounding the Cape of Good Hope, the Endeavour was well on her way home. She left Cape Town on 15 April and stopped only once more, two weeks later, at the island of St Helena. The last man to die aboard the Endeavour was Lt Hicks, Cook's second-in-command, who had come aboard the Endeavour already infected with tuberculosis. He died on 25 May, only weeks from home.

The Endeavour finally anchored in the Downs on 12 July 1771. Oddly enough, it was not Cook who got most accolades, but Banks and Solander. Banks in particular was feted, quickly becoming an accepted authority on all matters scientific, and finally President of Royal Society from 1778 until his death in 1820.

Many books tell about Cook's further exploits. There were more than a few of them; as indeed there were of many in his crew. But they have no bearing on the story we'll be following: that of the cannon and anchor that Cook abandoned off the Queensland coast in June 1770.