Squadron Leader Wallace Ivor Lashbrook - 102 Ceylon Squadron - 4 Group

Squadron Leader Wallace Ivor Lashbrook - 102 Ceylon Squadron - 4 Group .

. .

.

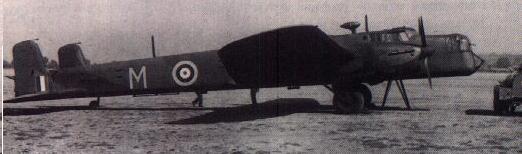

Motto - Attempt & Achieve - The MarkIII Version of the Halifax - Squadron Leader Lashbrook

work in progress

Contact was made some months ago with Wally Lashbrook, born on January 3rd 1913 in Chilsworthy, Holsworthy, Devon he currently resides in Scotland and has given his permission to publish the story of his evasion from capture as well as some facts on his career. He was shot down on the return leg of a mission to Pilsen in Czechslovakia on April 16th 1943. That operation saw his rear gunner killed and two others captured, Wally evaded capture and made his way to Spain via the Comet escape route. The story will focus on this evasion as provided to David Clark of the Remembering Project by Tom Burnard a childhood friend of Wally's. Tom wrote down Wally's story in 1980, that write up (THE INTREPID AIRMAN) with a few letters exchanged between Wally and myself will be the basis for most of what you will read here.

work in progress

Contact was made some months ago with Wally Lashbrook, born on January 3rd 1913 in Chilsworthy, Holsworthy, Devon he currently resides in Scotland and has given his permission to publish the story of his evasion from capture as well as some facts on his career. He was shot down on the return leg of a mission to Pilsen in Czechslovakia on April 16th 1943. That operation saw his rear gunner killed and two others captured, Wally evaded capture and made his way to Spain via the Comet escape route. The story will focus on this evasion as provided to David Clark of the Remembering Project by Tom Burnard a childhood friend of Wally's. Tom wrote down Wally's story in 1980, that write up (THE INTREPID AIRMAN) with a few letters exchanged between Wally and myself will be the basis for most of what you will read here.

At 16 Wallace Lashbrook, "Wally" entered the RAF as a Halton apprentice on January 15th 1929. The RAF took in young boys to train them as career mechanics and fitters at this very young age. This practice was still in effect in the 1950's. Acceptance into these programs was not an easy thing to obtain. He excelled at Halton and graduated as L.A.C. Fitter (aircraft engines) on the 24th of December 1931. He was awarded the First Fitters Prize.

To learn about the Apprentice program, Halton House plus some photos -Click on the Apprentice Badge

He was first stationed at RAF station Mountbatten in January 1932 employed as E.R.S. Fitter aero engines. While on station he represented the base in hockey and cross country inter unit sporting events. Here he worked with Aircraft man Shaw also known to many as T.E. Lawrence and Lawrence of Arabia

Both Wally and Aircraft man Shaw shared a love of motorcycles. Wally had a Rudge-Whitworth and Lawrence had his Brough Superior SS100.

..

..

Lawrence did not buy his SS100. It was a gift from his close friends, George Bernard Shaw and his wife Charlotte. Shaw later lamented that his present "was like handing a pistol to a would-be suicide". The SS100 is the bike Lawrence was riding when he crashed near his home in Dorset on May 13, 1935. He died six days later from severe head injuries. He wasn't wearing a helmet, and his head apparently struck the road or a tree. The motorcycle had only superficial damage. It recently sold at auction where the price was expected to top $3 million dollars(from article by John Carey)

In 1933 Wally volunteered for overseas duty and was assigned to 100 TE Squadron. He moved with the Squadron and from 1934 - 1936 was based in Selatar, Singapore as a fitter. Here he continued his athletic pursuits and was awarded the Station Colors for boxing and athletics. Tom Burnard describes Wally as "Wally was a pretty 'scrappy'

determined fellow even as a child.

In November 1936 he was selected for pilot training and returned to the UK initial training with Scottish Avaition, Prestwick on Tiger Moth aircraft. From here in January of 1937 he graduated to No. 2 Flying Training School at Digby for advanced training on the Hawker Hart and Hawker Audax.

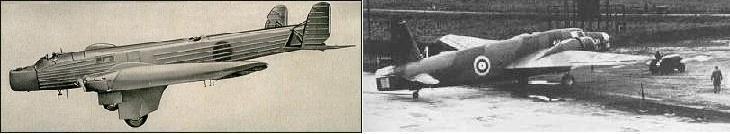

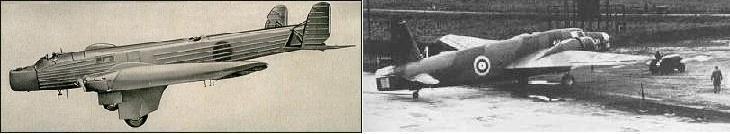

In August of 1937 he completed his pilots training and was promoted to Sergeant Pilot posted to No. 3 Group Bomber Command, 38 Squadron at Marham which was equiped with the Fairey Hendon twin engined aircraft. In March of 1939 with war clouds looming 38 Squadron was equiped with the Vickers Wellington. There were a several missions including a few leaflet raids but the unit did not see heavy action and had few causalties before being posted to the Middle East in November of 1940.

In August of 1937 he completed his pilots training and was promoted to Sergeant Pilot posted to No. 3 Group Bomber Command, 38 Squadron at Marham which was equiped with the Fairey Hendon twin engined aircraft. In March of 1939 with war clouds looming 38 Squadron was equiped with the Vickers Wellington. There were a several missions including a few leaflet raids but the unit did not see heavy action and had few causalties before being posted to the Middle East in November of 1940.

38 Squadron Crest MOTTO - BEFORE THE DAWN

MOTTO - BEFORE THE DAWN

With the conversion to the more modern aircraft Wally had already been posted to No. 2 Ferry pool at Filton. By this time he had acquired 369 flying hours. He stayed in this pool until mid 1940 ferrying 36 different types of aircraft and 375 in total including replacement Hurricane fighter aircraft to France just before the fall of that country.

..

.. It was in a Bristol Blenheim marked with the Finnish Rosen Cross (Straight Swastika) that Wally was first "blooded" by antiaircraft fire. Not by the enemys but by his own. He was ferrying the aircraft straight fromt he factory in Bristol to Liverpool for shipment to the Finnish airforce. The aircraft had been painted with the Finnish national insignia on the wings and rudder. This symbol was mistaken by the gunners at Cheltenham for Nazi symbols and there were several near misses. The gunners thought they were firing at a German JU88.

It was in a Bristol Blenheim marked with the Finnish Rosen Cross (Straight Swastika) that Wally was first "blooded" by antiaircraft fire. Not by the enemys but by his own. He was ferrying the aircraft straight fromt he factory in Bristol to Liverpool for shipment to the Finnish airforce. The aircraft had been painted with the Finnish national insignia on the wings and rudder. This symbol was mistaken by the gunners at Cheltenham for Nazi symbols and there were several near misses. The gunners thought they were firing at a German JU88.  His hours had grown to 1040 at this time and shortly after this the RAF Ferry Pools were disbanded. The duties were then handed over to civilian pilots known as the Air Transport Auxiliary.

His hours had grown to 1040 at this time and shortly after this the RAF Ferry Pools were disbanded. The duties were then handed over to civilian pilots known as the Air Transport Auxiliary.

September 1, 1940 at the height of the Battle of Britan, Wally is posted to 51 Squadron 4 Group flying Whitleys V's out of Dishforth, Yorkshire.

Here he completes a tour of 25 missions by January 1941. Targets include Berlin, Essen, Hamburg, Pilsen, Stettin, Keil, the Ruhr, Turin, Milan, and attacks on the channel ports. On incident in particluar was the attack on the Pirelli works in Milan Italy on October 20th 1940. The Whitlye aircraft di not have a heating system for the crews; they were swathed in bulky and cumbersome flight suits consisting of thick furlined leather trousers and jacket. In addition they wore a flying helmet and gauntlets inside of which were silk lined gloves as the Whitley crews (particularly the navigators) often received frostbite of the fingers. On this occasion, when they were over the target the aircraft was subjected to a withering heavy ack-ack fire which at times was all too close. As they left the target area after bomb release, Wally felt a warm wet area around the top of is thighs accompanied by severe pain. he suspected that he had been hit by shrapnel in a very private part of his anatomy. As soon as it was convienent he handed over the controls to his second pilot and left the cockpit. In order to carry out a through investigation he had to stand up in the narrow walkway and remove the bulky flight gear as well as his battle dress, this took some time. Finally removing all his gear he discovered that he had a nasty skin rash but that there was no blood. he redressed and took his position in the pilots seat. Four hours later when they landed he discovered that the petrol capsule he had been carrying for his cigarette lighter had burst causing the rash and unnecessary consern. For service above and beyond the call of duty Sgt. Pilot Lashbrook is awarded the DFM Distinguished Flying medal from the hands of King George VI.

In mid January 1941 he was sent to a special paratroop dropping course at Ringway, Manchester. On February 7th he took off from Mildenhall Suffolk in a Whitley V, number T4I65 for the Island of Malta along with seven other selected aircrews drawn from 51 (4) and 78 (4) Squadrons. Each aircraft were equiped with overland petrol tanks and carried six fully trained paratroopers. On February 11th they carried out the first paratroop raid of the war. Wally's aircraft was first on the target. The Calitri Aqueduct in Italy mission was the first use of paratroops by British forces in WWII. The raid itself was only partially successful. The drop made inland from Naples near Mt. Vulture. After the mission all 36 of the paratroopers and one Whitley crew whose plane was forced down were eventually captured. While still on the ground in Malta Wallys aircraft was damaged in a bombing raid by the Italian airforce. The main body of the group left Malta on Feb 15th but Wally was stuck until his aircraft could be repaired. Parts were scavenged from the remains of the famous Gladiator aircraft that defended MAlta in the early days, Faith, Hope and Charity.  On the return to Dishforth by the main party, Wallys wife Betty, who was living in the nearby village, on hearing the drone of aircraft naturally expected to see her hsband within an hour or so after their debeiefing. Instead, however, of being greeted by her husband, there appeared two of his fellow pilots carrying Wallys kitbag. Bettys anxiety was soon allayed on finding thet the kit-bag contained oranges, lemons and other goodies that were very hard to find in wartime England and not Wallys personal effects. The two pilots were able to assure her the her husband was merely delayed, and would be on her doorstep in a few days time.

On the return to Dishforth by the main party, Wallys wife Betty, who was living in the nearby village, on hearing the drone of aircraft naturally expected to see her hsband within an hour or so after their debeiefing. Instead, however, of being greeted by her husband, there appeared two of his fellow pilots carrying Wallys kitbag. Bettys anxiety was soon allayed on finding thet the kit-bag contained oranges, lemons and other goodies that were very hard to find in wartime England and not Wallys personal effects. The two pilots were able to assure her the her husband was merely delayed, and would be on her doorstep in a few days time.

Upon the return trip he was posted to 35 Squadron in March at Linton-on-Ouse, Yorkshire. There the squadron was in the process of re-equiping with mulit-engined aircraft in the group, the Handley page Halifax Mk.1. The flight commander was Flight Lieutenant Cheshire who would late be awarded the Victoria Cross.

On April 15th 1941 the first raids by Halifaxes over Germany were flown to Kiel Harbor Germany. Wally's Aircraft L9493 was hit by flak (anti aircraft fire)  over the target resulting in the wheels and flaps lowering under accumulator pressures. The resistance and impact on stability can be imagined. The early Halifax was not equiped with undercarrige "up locks" The result was a six hour return trip across the North Sea under these conditions which ran the fuel dry. Due to the fact that a JU-88 had been in the area the airfield lights had been doused and L9493 had been given up for lost as its slow pace had put if far behind the rest of the squadron. In the airfield circuit at 1500 feet the starboard engines spluttered out. The flight engineer was ordered aft to switch to another tank that hopefully still contained a few gallons necessary to land. In the stress of the moment the engineer forgot to turn off the empty starboard tank before selecting the new tank. This caused an airlock in the entire fuel system and the port engines died as well. At 1500 feet there was insufficient air space to do anything but prepare for the inevitible crash landing. The crew assumed their positions while Wally crossed his fingers and unable to see the ground could only go through the landing motions. Happily there turned out to be a small field below close to the base. With the flaps and landing gear down he brough the aircraft in at 100-110 mph. In pitch darkness the aircraft struck a tree at the root of the port wing just after touchdown and broke up into 4 sections. The cockpit containing the two pilots, the starboard wing with its engines still attached to the main part of the fuselage contained the flight engineer. The wireless operator, navigator, mid-upper gunner and the port wing with its engines was some distance from the rest of the wreck with the tail section containing the rear gunner even farther away. Remarkably there was no fire after the initial pandemonium but there was a disconcerting hissing sound. Wally called to his co-pilot, whose seat behind him had collapsed, to get out as fast as he could, and he himself tried unsuccessfully to open the overhead cockpit canopy to make his exit that way. His efforts were to no avail as the canopy had jammed. He therefore started to make his way in the pitch darkness to the rear of the aircraft. After two strides he fell out on to the ground, fortunately making a soft landing.

over the target resulting in the wheels and flaps lowering under accumulator pressures. The resistance and impact on stability can be imagined. The early Halifax was not equiped with undercarrige "up locks" The result was a six hour return trip across the North Sea under these conditions which ran the fuel dry. Due to the fact that a JU-88 had been in the area the airfield lights had been doused and L9493 had been given up for lost as its slow pace had put if far behind the rest of the squadron. In the airfield circuit at 1500 feet the starboard engines spluttered out. The flight engineer was ordered aft to switch to another tank that hopefully still contained a few gallons necessary to land. In the stress of the moment the engineer forgot to turn off the empty starboard tank before selecting the new tank. This caused an airlock in the entire fuel system and the port engines died as well. At 1500 feet there was insufficient air space to do anything but prepare for the inevitible crash landing. The crew assumed their positions while Wally crossed his fingers and unable to see the ground could only go through the landing motions. Happily there turned out to be a small field below close to the base. With the flaps and landing gear down he brough the aircraft in at 100-110 mph. In pitch darkness the aircraft struck a tree at the root of the port wing just after touchdown and broke up into 4 sections. The cockpit containing the two pilots, the starboard wing with its engines still attached to the main part of the fuselage contained the flight engineer. The wireless operator, navigator, mid-upper gunner and the port wing with its engines was some distance from the rest of the wreck with the tail section containing the rear gunner even farther away. Remarkably there was no fire after the initial pandemonium but there was a disconcerting hissing sound. Wally called to his co-pilot, whose seat behind him had collapsed, to get out as fast as he could, and he himself tried unsuccessfully to open the overhead cockpit canopy to make his exit that way. His efforts were to no avail as the canopy had jammed. He therefore started to make his way in the pitch darkness to the rear of the aircraft. After two strides he fell out on to the ground, fortunately making a soft landing.

There was just sufficient light outside the aircraft for him to call the crew together and take stock of their injuries which, in the circumstances, were, unbelievably, of a minor character. One member, however, was missing - the rear gunner. His name was called and, in very strong language, a reply came from an area 10 or so yards down the hedgerow. The gunner was trapped in his turret, and he was rescued with the aid of a fire-axe retrieved from the main wreckage. he was only mildly concussed and for a while after his released he reeled like a drunken sailor. The hissing noise comming from the aircraft had now subsided and in the dawn light, it was seen to be due to the automatic inflation of the dingy which was now perched on the wing fully inflated.

As the wireless operator, Sgt. Somerville, was uninjured he was left in charge of the crew whilst Wally also uninjured, went off to seek some help. Some two hundred yards from the scene of the crash he came to the River Swale across which, in the half light, he could see a cotage. He decided to wade the river which turned out to be muddier, deeper and colder than he anticipated. However, he ploughed on his murky way until finally he reached the far bank and thence to the cottage. He banged on the door repeatedly, until at last the upstairs window opened and a man's voice told him to "bugger off". It appeared that he thought the stranger at his door was a German as his sleep had been disturbed by the air-raid siren and gunfire.

Wally persuaded him otherwise. The home owner dressed and rode off on his bicycle to telephone for assistance. Before the man left Wally told him he would wait in the riad to lead the ambulance to the crash. Wally waited a miserable 45 minutes, wet and muddy as he was, and without a dry cigarette. He was a heavy smoker in those days. The ambulance appeared with the Squadron Commander, Squadron leader Willie Tait, aboard who explained the delay. The first ambulance called out had overturned on the way to the scene. Two fo the crew subsequently did not perform any further flying duties and were posted elsewhere.

Following this crash landing all Halifax aircraft were withdrawn from operations in order to be fitted with mechanical "up-locks" to the undercarrige, and off-cocks placed in the hydraulic pipelines to the flaps accumulator. Operations were resumed as modified aircraft became available.

Monty Burton was a navigator in the RAFVR (Royal Airforce Volunteer Reserve)in 1939 and was in 35 Squadron in those days. He provides a bit more on the consequences of the problems with the early Halifax and the temporary fix.

Monty:

"I served as a Navigator on 35 Squadron at the same time as

Wally Lashbrook and was grounded with the rest of the squadron directly after

his crash. As a result of the crash, and the delay of our activity

Winston Churchill became so incensed that he had our squadron commander

and all the rest involved (including Lord Beaverbrook) to Whitehall and

threatened all concerned that if the matter was not fixed post haste

heads would roll and Air Marshalls would be busted to airmen.

The temporary fix was in place in three weeks. As navigator it was

my job to push a lever in the cabin to put a rod out under the wheels to

prevent them from coming down in event of an engine failure to operate

the hydraulic pump." Monty served originally on #10 Squadron(Whitleys) before transferring to #35. His

second tour was on Wellingtons and he later became a pilot. Monty trained

on Tiger Moths and Oxfords but the war ended before becoming

operational.

and he later became a pilot. Monty trained

on Tiger Moths and Oxfords but the war ended before becoming

operational.

*************************

On May 26th 1941 under Kings Regulations ACI paragraph 652 Flight Sargent Wallace Ivor Lashbrook is granted a commission as an Officer. June 18th two more raids are flown after Halifax aircraft have modification made to hydraulic systems. By this time his flying hours had grown to 1484. On June 17th 1941 Wally carried out a air test on his modified aircraft in preparation for a daylight raid on Hamburg for the following day. He missed the raid as on his way to the airfield from his off base home, his motorcycle was involved in a collision with a three ton lorry. He sustained a compound fracture of the right leg, was concussed, and woke up in the ambulance on the way to the hospital. Later he considered himself to be lucky as the Hamburg day light raid proved to be a costly affair for the squadron. He was five months recupperating from the accident and returned to operations in November 1941.

BR>

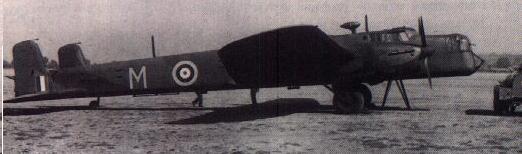

Upon rejoing the group he was assigned to No. 28 Conversion unit for the conversion of Whitley pilots to Halifax aircraft at Leconfield, Yorkshire. In December 1941 he is finally attached to 102 Squadron as a conversion instructor at Topcliffe and various airfields. Tom Burnard the writer of this profile was trained by Wally Lashbrook and can vouch for the quality of the conversion training he recieved. Wally participated in the second 1000 plane raid on Essen while engaged in this role.

The thousand plane raids were as much a propaganda ploy as they were devstating strikes and morale boosters. To manage a thousand planes Bomber Harris had to scrape together every aircraft from Bomber command as well as Coastal and training units.

102 Squadron Conversion Flight. Wally is Acting Squadron commander and sitting in the center.

In 1942 he is appointed to Flight Commander of 102 Squadron Conversion Flight. At this time he is promoted to acting Squadron Leader. Following the final conversion of 102 Squadron in March of 1943 Wally is posted to 1664 Conversion Unit as Flight COmmander. For his work in converting 137 pilots in 4 Group during this time he recieves in March 1943 a MENTION IN DISPATCHES. April 10th 1943, joining 102 Ceylon Squadron based out of Pocklington Yorkshire as its operational Flight Commander he is tasked to take a selected crew to orbit the target taking photographs at the end of the bombing run by the other aircraft. A decidedly dangerous assignment as they could be well silhouetted against the smoke, clouds and searchlights for the German 88 Flak, not to mention the Luftwaffe nightfighters surrounding Stuttgart that April 14th night. After his run in to drop his bombs on the target he re-entered the target zone, this time to take aerial photos which would be timed to include the results of the attacks by the main-stream bombers. He selected his crew for this mission on April 11th 1943. All were experienced men, one of whom, the flight engineer, was his room mate at Halton as a teenager. They had not seen eachother since December of 1931. When they returned the crew was debriefed and a light plane came for Waly to take him to London. He had the additional task of relating the experience for the BBC broadcast The BBC 9 O'Clock News "On the Stuttgart Raid". He was introduced to the listeners by Alva Liddell, the well known news-reader of the day. When the broadcast was finished he was flown directly bask to Pocklington and then to bed to be ready for the next nights operation.

not to mention the Luftwaffe nightfighters surrounding Stuttgart that April 14th night. After his run in to drop his bombs on the target he re-entered the target zone, this time to take aerial photos which would be timed to include the results of the attacks by the main-stream bombers. He selected his crew for this mission on April 11th 1943. All were experienced men, one of whom, the flight engineer, was his room mate at Halton as a teenager. They had not seen eachother since December of 1931. When they returned the crew was debriefed and a light plane came for Waly to take him to London. He had the additional task of relating the experience for the BBC broadcast The BBC 9 O'Clock News "On the Stuttgart Raid". He was introduced to the listeners by Alva Liddell, the well known news-reader of the day. When the broadcast was finished he was flown directly bask to Pocklington and then to bed to be ready for the next nights operation.

The squadron had its own song, one of the refrains being.

And when you come to 102And think that you will get right throughThere's many a ------ who thought like youIt's foolish but its fun

Strangely enough, though Wally Lashbrook could not have known it 102 would be his last operational squadron, and one of which he was destined to be a member of for only 7 days.

Shot Down April 16th 1943 - Target Pilsens Skoda Munitions Works in Czechslovakia.

The target for the night of April 16th was at the limit of operations mounted from the United Kingdom, the Skoda Works at Pilsen in Czechoslovakia. The routine was as before - identify the target, bomb it, and photograph the results of the main wave attack. The target was located and successfully bombed but the taking of the photographs proved to be more hazardous. The Lancaster bombers, who normally flew at a higher altitude than the Halifaxes, had now arrived over the target. Although evasive action could be taken with regard to enemy ack-ack fire, there was nothing that could be done to avoid being bombed from above. Wally wasted no time, took his photographs, and hastily set a course for home. There were no further incidents on the flight home until the aircraft reached the Belgian/French border.

It was a clear night - too clear - and they had been flying over a layer of stratus clouds at 9000 feet. As this broke up Wally realized that they were extremely vunerable to night fighter attack. He had already seen some of our aircraft shot down near by and called on the intercom, "watch out for the fighters; there's a Lanc going down on the port, keep your eyes -------" No sooner had he said this that the aircraft has hit by a single long cannon burst from an unseen night fighter just below them. They never had a chance to take evasive action or fire in their own defense.

[note: This was the favored tactic of the nightfighters. The approach was from below with the Schrage Musik (Jazz Music) cannon firing obliquely into the wings near the fuselage and between the engines to flame the fuel tanks. They also took out the rear gunner to prevent him from hitting them first. The Halifax and Lancaster did not have a ball (belly) turrett like the American B-17. Most of the RAF bomber losses were like this, they never knew what hit them.]

Halifax HR663 DT-Y was shot down by an Lt. Rudolf Altendorf of NJG 4 2nd Squadron flying an ME-110 .  There are some Belgian historians who are in posession of Herr Altendorf's radio transmission logs. It may be possible to include the record of this victory at some time. Herr Altendorf survived the war, Wally's Halifax was his 17th confirmed victory. The Halifax crashed near Mez close to Givry and La Fagne in Belgium at the French border at around 4 am. The fuselage and port wing were riddled and set aflame, the rear gunner pilot officer Williams

There are some Belgian historians who are in posession of Herr Altendorf's radio transmission logs. It may be possible to include the record of this victory at some time. Herr Altendorf survived the war, Wally's Halifax was his 17th confirmed victory. The Halifax crashed near Mez close to Givry and La Fagne in Belgium at the French border at around 4 am. The fuselage and port wing were riddled and set aflame, the rear gunner pilot officer Williams  was killed out right and the upper gunner Sgt. Neil was wounded. The port wing reminded Wally of a welding torch and the aircraft started to spiral to the left. Wally could not control the spiral with full rudder and aileron so he gave the order to abandon the aircraft. The upper gunner was helped from his turrett, a parachute pack was clipped on the front of his harness and he was then bundled out of the rear door. The bomb aimer,Flying Officer Martin

was killed out right and the upper gunner Sgt. Neil was wounded. The port wing reminded Wally of a welding torch and the aircraft started to spiral to the left. Wally could not control the spiral with full rudder and aileron so he gave the order to abandon the aircraft. The upper gunner was helped from his turrett, a parachute pack was clipped on the front of his harness and he was then bundled out of the rear door. The bomb aimer,Flying Officer Martin  and the navigator Flying Officer Bolton, and the Wireless operator,Sgt Laws went out through the foreward hatch. Wally was in the cockpit trying to hold the aircraft in trim until everyone could get out was down to 3000 feet. Flight Sgt Knight clipped a parachute pack on Wallys harness and then dived through the front hatch opening. Wally remembers thinking at the time "doesn't he look like a frog?" as his arms and legs spread-eagled in the rush of the air. He then let go of the controls and the spiral became a spin. He was caught by the centrifugal force of the spinning aircraft. His parachute harness caught on the trim indicator and had to be unhooked. He still had his helmet on with the intercom leads becomming entangled around the control column. He tore off the helmet thinking "I don't need this now and I won't have to sign for it when I reach the ground". He made two unsuccessful attempts to get through the hatch but kept being thrown about by the spin. By pulling himself to hatch and popping his parachute while leaning partially out of the aircraft, the parachute pulled him free like a champagne cork out of a bottle barely 500 feet from the ground. He landed 100 yards from the crashed of the aircraft in a matter of seconds after its impact! As he hit the ground he though "I'm alive" and then his bottom connected with the earth, followed by a sharp crack to the head. His next thought was "that killed you anyway". While laying on his back in the lane he saw his flight engineer drifting down in his parachute a half-a- mile away. They would not see each other again until wars end.

and the navigator Flying Officer Bolton, and the Wireless operator,Sgt Laws went out through the foreward hatch. Wally was in the cockpit trying to hold the aircraft in trim until everyone could get out was down to 3000 feet. Flight Sgt Knight clipped a parachute pack on Wallys harness and then dived through the front hatch opening. Wally remembers thinking at the time "doesn't he look like a frog?" as his arms and legs spread-eagled in the rush of the air. He then let go of the controls and the spiral became a spin. He was caught by the centrifugal force of the spinning aircraft. His parachute harness caught on the trim indicator and had to be unhooked. He still had his helmet on with the intercom leads becomming entangled around the control column. He tore off the helmet thinking "I don't need this now and I won't have to sign for it when I reach the ground". He made two unsuccessful attempts to get through the hatch but kept being thrown about by the spin. By pulling himself to hatch and popping his parachute while leaning partially out of the aircraft, the parachute pulled him free like a champagne cork out of a bottle barely 500 feet from the ground. He landed 100 yards from the crashed of the aircraft in a matter of seconds after its impact! As he hit the ground he though "I'm alive" and then his bottom connected with the earth, followed by a sharp crack to the head. His next thought was "that killed you anyway". While laying on his back in the lane he saw his flight engineer drifting down in his parachute a half-a- mile away. They would not see each other again until wars end.

THE EVASION AND TRIP DOWN THE COMET LINE

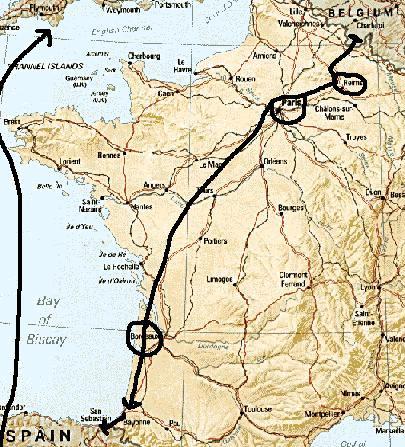

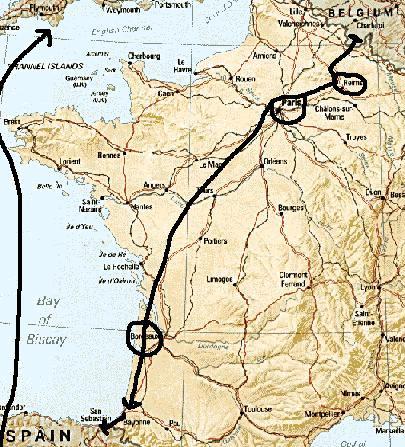

Wally managed to evade capture by slipping through France to Spain arriving back in the UK on June 22nd 1943.

Quickly gathering up his parachute he quickly made off across the fields, and came to a suitable spot where he could dispose of it by treading it into the marshy ground. He his his life jacket in a hedgerow. He then followed a forrest track for a few hundred yards, until he heard voices which caused him to lay flat on the ground, hiding his face. Not five yards away from him he could hear two men talking, but he could not understand their language. (Wally learned later that it was Flemish). To his relief the men hurried past towards the burning aircraft without noticing him.

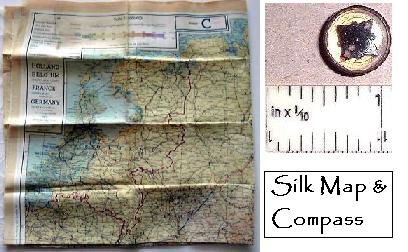

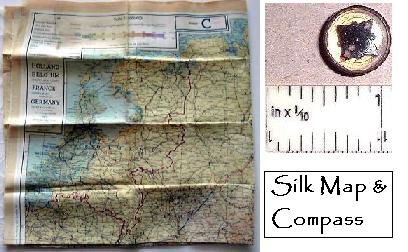

He quickly got up and continued along the forrest track until he notices from a sight of Polaris (the north star), that he was walking in a easterly direction. As he knew that his approximate location was either Northern France or Southern Belgiul, he changed his direction of travel to the south-west. As he walked on he tried to ensure that he left no obvious trail in the dew dampened grass by jumping to one side and then to another. After following a stream he came to a large wood and decided to hide there for a while, the time being about 6 a.m. The wood was partially cleared and he made himself a den from nearby branches. He checked the contents of his pockets to dispose of any compromising documents, and to examine his escape kit. The map in his escape kit confirmed his approxmiate location.

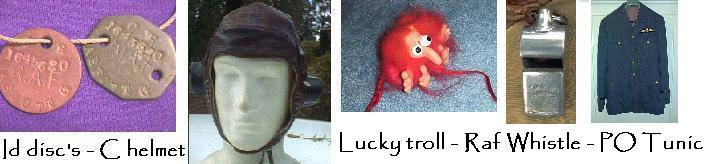

He lay in his hideout all that day and although he heard voices of beaters (searchers looking to flush him out), he remained undisturbed. For food he took a few Horlicks tablets (malted milk balls) and a bar of chocolate. He also indulged in one cigarette. At 10 p.m. he decided that it was dark enough to get going, and off he set in a south westerly direction, now making use of his escape kit compass.

WW2 RAF & British Forces standard half inch escape compass. Brass base (black painted) with star shaped magnetised pointer with luminous dots marked to show "North". Glass topped. Carried by allied aircrews & also formed part of ration packs, escape packs etc. The same compass was also hiddden in such items as shaving brushes, lighters, collar studs & uniform buttons etc.

Whilst following a minor road he came across a signpost, which confirmed his approximate position as being just south-east of Bois de Chimey and north-east of Hirson. He then came to a farm house where he noticed a milk churn. He quietly removed its lid and began to help himself to the milk, making use of a rubber bottle which was part of his escape kit. He was disturbed by a barking dog and quickly retreated to the nearby forrest. As dawn broke he was still making his way through the forrest, and about 9 a.m. he heard voices and hid behind a tree. There then appeared two old people, a man and a woman, both possibly over 70 years old, gathering small plants and leaves into a basket. Wally came out from behind the tree and in his best schoolboy French, explained who he was, and that he was very hungry. After they had recovered from their surprise at seeing him, they told him to hide in the nearby undergrowth until they returned. About two hours later they appeared gathering plants and as they past his hiding place they dropped a bottle of beer and half a loaf of bread. With their fingers to their lips they contiued their walk. As they disappeared Wally left his cover to collect the presents which he was glad to devour, the French loaf unexpectedly containing a slice of meat.

He continued to travel, now in a southerly direction, and eventually crossed the French-Belgian border. This was marked by a number of partially camoflaged dummy field guns. On reaching a small farmstead he tried to snatch a few hours of sleep in a disused outhouse which contained some straw. It proved, however, to be too cold and uncomfortable so he decided continue his journey. Just before dawn broke he discovered a disused cowshed with a small loft containing some bales of hay. Sleep still eluded him, so he took the opportunity to remove his wet socks and try to dry them by following the sunbeams piercing the holes in the roof.

About mid-afternoon he decided to resume his journey, keeping out of view by staying close to the hedgerows. A cowman he met who was milking his cows in a field, told him to "beat it". He kept shouting Les Boches - allez - allez - allez. After wading a river near St. Mickel, east of Hirson, as the night fell, he continued plodding on. It was now apparent to him that he would soon need to seek help of some sort or, at the very least have a good square meal.

Just as dawn broke on that Monday morning, the 20th of April 1943 he came across a small isolates cottage and waited nearby until the first light came on. His knock at the door brought a response from the other side of the door: 'Qi est la?' To which Wally cautiously replies: 'Avaiteur anglais.' The door was then unlocked and he was beckoned inside. The man, who proved to be a game keeper, called his wife who was upstairs, to come down. They were both aged about 25-30 years old, and she was holding their baby in her arms. (Many years later in 1967 Wally again met the "baby" this time sh had her own baby as she was then grown up and married.) After a hearty breakfast of eggs, bread and butter was provided, which was washed down with plenty of ersatz coffee. The game-keeper's name was Henri Michel and he offered Wally the use of his shaving brush and open razor. Lacking the dexterity to use this unaccustomed instrument Wally was soon in difficulties. Henri came to his rescue, and gave him a quick shave while Wally reclined in a chair. As his moustache would be out of place on a Frenchmans face Henri soon removed that, as well as the whiskers.

After the shave henri showed him a bed upstairs where he could get some much needed sleep, whilst Henri slipped off to buy some rations with the French currency Wally gave him from his escape kit. When he returned he indicated that Wally must discard his uniform and get into a old suit of Henri's. Wally is far from being a large person, but the suit provided by Henri was several sizes too small. The sleeves seemed to be almost up to Wallys elbows and the trouser legs half-way up to his calves. He was further concerned as he had forgotten to wera his RAF identy discs, which he would now be very much in need of, should he unfortunately be captured. His uniform was buried in the wood inside a milk churn to be recovered said Henri: "Apres la guerre".

Henri informed Wally of the arrangements for the following day. Then at 5 a.m. on Tuesday morning they set off on bicycles for the nearest village, Yviers. On the first descent Wally became aware that his bycycle had no brakes, which Henri was unaware of, for he registered a frown of disapproval as Wally careered past him. On arrival at the village they joined a party of workmen aboard an open truck to head for Montcornet, the nearest town to the railway. At the station Henri bought tickets for Rheims. As the train departure was not due for some time, they left the station and made for the nearest estaminet (resturuant/pub). There were half a dozen customers inside and Henri gave his order to the barman. Somewhat to Wally's consternation Henri then turned to him and asked him what he would like. Waly managed to mumble 'biere' and the barman obliged without further ado.

Shortly afterward they left for the railway station, Wally following behind Henri, and at the station the bicycles were put in the guard's van. Wally boarded the train, all the time keeping a watchful eye on Henri who just entered the full compartment. Wally remained nearby in the corridor. Just before the train departed a squad of German soldiers arrived and boarded the train. Wally's heart sank at the though that they were looking for him and that 'the game was up'. His initial fears were allayed as the train being full, some of the solders took up positions on either side of him in the corridor. One actually asked him in French: 'Quelle heur est il?' Wally wisely decided not to air his schoolboy French and held up his wrist for the German soldier to read his watch. Fortunately the soldier was unaware that the watch had anything but a French look to it.

Henri and Wally dismounted the train at the station before Loan, collected the bicycles and made off up a small road to some cottages. There they were welcomed by a friend of Henri's named Albert who was also a game keeper. A substantial meal was already being prepared, and Wally was made very welcome. In the short period that he was enjoying their hospitality, about two or three hours, Albert persuaded Wally that when he reached the U.K. he should ask the B.B.C. he should ask them to transmit a coded message. The message was to be 'Albert est bien arrive.' It was duly broadcast by the B.B.C. some eight weeks later, and when Wally visited them in 1967, his helpers were able to confirm that most of them had heard the transmission.

Following a long discussion between Henri and Albetrt, Henri left to catch a train to Rheims via Laon where it was known that the Germans had set up a check point. he took with him a basket full of fruit and vegatables. In order to avoid the checkpoint at Laon it was decided that Wally should ride pillion on Alberts motorcycle, and pick up the train at a station beyong Laon. Albert made a lightening dash through the woodlands, following small tracks. Wally would give him full marks as a dirt track or rally rider. They arrived in time to meet the train and Henri could be seen at a window. Wally boarded at that point and remained in the corridor. On arrival at Rheims  Henri slipped the basket of fruit and vegatables to Wally in order to smooth his way through the ticket-barrier. The ruse was successful. He trailed Henri through the crowded streets of Rheims until they came to a detached house in the residential area. The house belonged to Mme. Lechanteur, a very brave woman who, after the war, was decorated by the British, French and U.S. authorities for the very great assistance that she rendered to the Allied Forces at great peril to herself. Wally remained hidden upstairs for six days. He did not know until the war was over, that Mme. Lechanteur's husband was a doctor, and carried on his practice in the house in the normal way.

Henri slipped the basket of fruit and vegatables to Wally in order to smooth his way through the ticket-barrier. The ruse was successful. He trailed Henri through the crowded streets of Rheims until they came to a detached house in the residential area. The house belonged to Mme. Lechanteur, a very brave woman who, after the war, was decorated by the British, French and U.S. authorities for the very great assistance that she rendered to the Allied Forces at great peril to herself. Wally remained hidden upstairs for six days. He did not know until the war was over, that Mme. Lechanteur's husband was a doctor, and carried on his practice in the house in the normal way.

During his enforced stay Wally was interrogated by a young man, Christian Hecht, who was the leader of the local French Resistance organisation. He needed to be assurred that their ward was authentic and not a German plant. He was reassured by the mention of the B.B.C broadcast of the Stuttgart raid. M. Hecht had in fact listened to the broadcast and now recalled Wallys voice. Hecht said that he could get a letter through to England for him, so that Wallys wife would know that so far at least, he was very much alive. Withing a few days a mesage was delivered to his wife, Betty, then living with her parents at Prestwick. Unfortunately, shortly afterwards, a second telegram came from the same source stating that the news was not confirmed.

On April 26th, 1943 Wally was informed that he must move as the Germans were carrying out random searches. He was to go to Mailly Champagne, about 12 km. south of Rheims. He was to stay with the local butchers named De Kegal. To get there Wally was to travel in the back of a butchers van driven by M. Hecht. As there might be an unexpected road block to negotiate, Hecht handed Wally a loaded revolver. He explained that should Wally's true identity become known or even guessd at, the M. Hecht's life would be at immediate risk. Should this happen, therefore they would both have to shoot their way out of danger. Fortunately, no such event occured and they arrived at the De Kegal's house. The De Kegal family occupied a detached house with its own court yard entered through a archway from the village main street. Their household consisted of M. and Mme. De Kegal, their five children and a Flemish speaking aunt from Belgium. The eldest child, Madeleine, was 11 years old and the only child who knew Wallys true identity. For the benefit of the other children he assumed the title of Uncle Albert from Belgium visiting their auntie.

Madeleine was the sole of discretion. One day, while the family and Wally were sitting down to a meal, there was the tramp of boots in the courtyard, followed by a banging on the door. Madeleine straight away got up and help the stairway door open for Wally t make a bolt for the loft. She then quickly swept up the place setting and put all the evidence in the kitchen sink, with the rest of the dirty dishes, before her mother had answered the door. Luckily it proved to be a false alarm. Wally's language difficulty was not lost on the 9 year old child who niavely asked: 'How is it that Uncle Albert can't understand us?' After seven days in the casre of the De Kegal's it became evident that Wally's presence was becomming known. M. Hecht decided that it was time to move him elsewhere and arrived pushing a tanden bicycle. It is perhaps appropriate perhaps to mention at this point that M. De Kegal was later executed by a German firing squad in 1944 for his Resistance activities.

M. Christian Hecht took the front seat of the tandem bicycle, and after a little initial wobbling, the pair of them made their way along the woodland paths and miinor roads to the champagne vineyard of M. Cheminon in Villers Marmey. Whilst there a few days Wally volunteered to give hand in the cellars sorting potatoes and bottling the wine. He much enjoyed the latter chore though M. Cheminon's stocks suffered accordingly. He must have been forgiven as they have, since the end of the war, exchanged Christmas cards continuously. While spending a busy 5 days with the Cheminon's family, Christian Hecht found another house in the village of Beine. Wally's room was at the back of the house on the ground floor. His window faced the yard in which there was always a bicycle ready. The yard at the back opened on to a small road, his intended escape route in any emergency. The house belonged to M. Georges Lundy who lived with his mother and a house keeper. Wally was well looked after here for some 10 days when he was visited by another helper form the Resistance, M. Joseph Berthet. He had a flat in Rheims, and arrangements we made for Wally to go there. It was paerticularly gratifying for the two Messers. Lundy and Berthet when some tow months later the B.B.C. message 'Albert est bien arrive' was briadcast and heard by them. It was greatly regretted that both these brave patriots were arrested by the Gestapo the following year and sent to the concentration camp at Dachau, never to return. A commerative plaque has been installed in Beine in memory of the villages greatest patriot.

At dawn on the following day Wally set off on a bicycle escorted by Chriatian hecht heading for M. Berthets flat in Rheims. After nearly a week he was moved to another flat, that of a middle-aged spinster, Mlle. Germaine Geoffroy. She was contemptuous of the Germans and utterly fearless. After he left there, Wally heard that she even had concealed weapons in her flat. All those whom she helped will be pleased to know that the Germans never found her out. During the six days in Mlle. Geoffroy's flat Wally was informed of the plan for his further movements. On the day he left the flat he caught a train for Paris, a young lady named Madeleine, about 19 or 20 years old, acted as his guide. On arrival in Paris they took the Metro underground to a station near Notre dame.  From the station Wally followed Madeleine to the home of the Waeles family who occupied a flat on the sixth floor of an apartment block. The apartments were built round a central court, each with a steel railed veranda overlooking the courtyard. Should the Germans carry out a search, the method of escape was to leap from the veranda rail to the one opposite, but at the next level, a jump estimated to be at least 12 feet. As the sixth floor flats were some 60 feet above ground level, Wally was thankful that he was never required to test the escape plan, though he was assured by a French student that he had successfully made the leap.

From the station Wally followed Madeleine to the home of the Waeles family who occupied a flat on the sixth floor of an apartment block. The apartments were built round a central court, each with a steel railed veranda overlooking the courtyard. Should the Germans carry out a search, the method of escape was to leap from the veranda rail to the one opposite, but at the next level, a jump estimated to be at least 12 feet. As the sixth floor flats were some 60 feet above ground level, Wally was thankful that he was never required to test the escape plan, though he was assured by a French student that he had successfully made the leap.![]()

Whilst in the care of the Waeles family, various helpers tool Wally on shopping expidetions for a better suit of clothes and to be photographed for a false identy card. Mme. Waeles was later imprisioned for 12 months on suspiscion of helping escapers. To while away her time in prision she embroidered a table-mat from the threads pulled from her clothes, her sheets, and blankets, using a chicken bone for a needle. The table-mat is now in Wally Lashbrooks proud posession, having been given to him after the war by Mme. Waeles. Having been warned of the possibility of her mothers arrest, her daughter, Mart-marie, found sanctuary in Vichy France. She later married a padre of the British Army.

In early June 1943 the final stages of Wally's German evasion began. He had initially two guides, Madeleine, as before, and a Belgian whose code name was Franco. They went by Metro to the Gare du Sud. Madeleine bought tickets for their destination, Bordeaux, but omitted unintentionally to give Wally his ticket. Whilst waiting with the guides for the train to pull in, Wally noticed another group of travelers a few yards away. To his utter amazement he saw that the tallest member of the party was none other than one of his aircrew, his bombadier, Alf Martin. Simultaneously they noticed eachother but, in the circumstances, the only form of recognition that was possible was a knowing smirk by each of them. As the train pulled in Madeleine indicated Wally's corner seat which had been reserved, she was taking her seat in another compartment. There were three other passengers in Walys compartment as the train pulled out of the station. He adopted a casual manner, pretending to read a French magazine, turning the pages at appropriate intervals of time. In due course the ticket inspector appeared: 'Billets, s'il cous plait'. His three companions produced their tickets whilst Wlly, in a cold sweat, could only offer a shrug of the shpoulders and : 'Mon billet est avec mademoiselle', waving his hand nonchalantly up the carriage. The inspector gave a knowing grin and moved on. Wally's sigh of relief was no doubt distinctly audible; at all events all three of his fellow travelers got out at the next stop. It seems quite probable that they were changing compartments so as to not become involved in any incident. Like the rail-traveler in 'Three Men in a Boat' transporting his cheese, Wally now had the compartment to himself. Sometime later the compartment door slid open and there stood a lovely girl. She started to chatter hurridly, none of which Wally understood. Perhaps she was enquiring abou empty seats. Wally's stock phrase 'Je ne sais pas, mademoiselle' brough the response; Aviateur anglais, eh?' to which he replied: Oui mademoiselle'. She gave a friendly smile and a 'bon voyage' and gracefully retreated, closing the corridor quietly behind her. The remainder of the jpourney to Bordeaux passed without further incident, a warning of the trains arrival being indicated by Madeleine from the corridor.

As she left the train Wally followed at a discreet distance. Once they were clear of the railway station they joined up with the other party comsisting of his bombardier, Alf Martin, A U.S.A.F. aircrew member, Doug, and their guide.  Mme Witton, Doug Hoehn and Alfred Martin. Doug was shot down during a daylight raid by Flying Fortresses.

Mme Witton, Doug Hoehn and Alfred Martin. Doug was shot down during a daylight raid by Flying Fortresses.  he had a harrowing tale of his fellow crew members being machine gunned as they floated down to earth by parachute. He himself did a free fall from 25000 feet to about 2000 feet before releasing his parachute and landing safely. A few minutes later his other guide, Franco, joined them and they all made for a nearby cafe for drinks and relaxation. They occupied a pavement table and discussed future plans. Franco told them that shortly they must return to the station to catch a train for Dax, a journey which would be of about two hours duration. The party then left the cafe for a restruant for the mid-day meal..At the next table there sat a party of German soldiers which included an officer. Wally was understandably fearful lest some untoward incident should, at this late hour of their evasion, give their game away. Fortunately, nothing occured and the evaders were thankful for that, and glad to once more make their way to the station. here they boarded the train to Dax, guided by Franco, and leaving Madeleine and the other guide in Bordeaux. Madeleine was later betrayed to the Gestapo in 1944 and sent to a concentration camp. The camp was liberated by the American troops and Madeleine was returned home to her mother. She had suffered so terribly at the hands of her captors, and was so emaciated, that she survived only a few days after reaching home.

he had a harrowing tale of his fellow crew members being machine gunned as they floated down to earth by parachute. He himself did a free fall from 25000 feet to about 2000 feet before releasing his parachute and landing safely. A few minutes later his other guide, Franco, joined them and they all made for a nearby cafe for drinks and relaxation. They occupied a pavement table and discussed future plans. Franco told them that shortly they must return to the station to catch a train for Dax, a journey which would be of about two hours duration. The party then left the cafe for a restruant for the mid-day meal..At the next table there sat a party of German soldiers which included an officer. Wally was understandably fearful lest some untoward incident should, at this late hour of their evasion, give their game away. Fortunately, nothing occured and the evaders were thankful for that, and glad to once more make their way to the station. here they boarded the train to Dax, guided by Franco, and leaving Madeleine and the other guide in Bordeaux. Madeleine was later betrayed to the Gestapo in 1944 and sent to a concentration camp. The camp was liberated by the American troops and Madeleine was returned home to her mother. She had suffered so terribly at the hands of her captors, and was so emaciated, that she survived only a few days after reaching home.

On arrival at Dax their party of four tool a road going south and on the outskirts of town each of them was given a bicycle to make their way to Bayonne. Wartime bicycles were not of the highest quality, and it was not long before Wally had a punctured tire adn Alf's chain broke.

The Puncture was repaired at the roadside, but Franco was obliged to return to Dax to obtain a new chain.

Following the chain replacement they set off once again for Bayonne, keeping to minor roads and thus covering a distance of about 45 miles. During the journey a German military vehicle pulled up alongside Wally as he pushed his bicycle up a hill. Out got two NCO's who it later transpired, enquired in German the way to some nearby village. Wally was fortunate thet his repeated 'Je ne sais pas' was sufficient to allay suspecion as to his real identity. At about 10 p.m. they reached the outskirts of Bayonne where they hid their bicycles in an old garage, and then waited until it was really dark. They then followed Franco through the streets to a riverside cafe  owned by an incredibly fat and jovial Frenchman. He soon prepared an enormous meal for them, with plenty of wine, followed by coffee. They all slept in an upstairs room until about mid-day.

They left the cafe in the early evening. Wally and Franco collected the bicyclkes and they set off for St. Jean de Luz in Navarre. Again they cycled along side tracks, and cart-tracks even, to avoid any checkpoints on the main roads. The journey lasted a greuling three and a half hours, and then about 9:30 p.m. because it was still light, they reamined on the outskirts of town. They whiled away the time as best they could, showing particular interest in a fisherman on the riverbank unsuccessfully casting his line. While they were so engrossed a German Soldier, armed with a rifle, came and joined them. he turned to Wally and in bad French asked if the fisherman had caught anything. Wally rapidly decided that as his French for 'He hasn't caught anything' was beyond his present linguistic capabilities, he decided to compromise with a loud 'un grand poisson'. The German soldier seemed well satisfied with this, and with a 'Bonjour monsieur', he was on his way.

owned by an incredibly fat and jovial Frenchman. He soon prepared an enormous meal for them, with plenty of wine, followed by coffee. They all slept in an upstairs room until about mid-day.

They left the cafe in the early evening. Wally and Franco collected the bicyclkes and they set off for St. Jean de Luz in Navarre. Again they cycled along side tracks, and cart-tracks even, to avoid any checkpoints on the main roads. The journey lasted a greuling three and a half hours, and then about 9:30 p.m. because it was still light, they reamined on the outskirts of town. They whiled away the time as best they could, showing particular interest in a fisherman on the riverbank unsuccessfully casting his line. While they were so engrossed a German Soldier, armed with a rifle, came and joined them. he turned to Wally and in bad French asked if the fisherman had caught anything. Wally rapidly decided that as his French for 'He hasn't caught anything' was beyond his present linguistic capabilities, he decided to compromise with a loud 'un grand poisson'. The German soldier seemed well satisfied with this, and with a 'Bonjour monsieur', he was on his way.

About 10:30 p.m. Franco rejoined them, and they were shortly joined by abother guide who was to lead them across the fields to the next rendevous, a farm house in the foothills. Before starting, each was given a pair of rope sandals to prevent slipping during the forth comming rock climbing in the mountains. They were given cotton trousers for rapid movement, and to enable them to change into their own dry ones after crossing the river, and befor entering San Sebastian. Their own trousers were bundled into a backpack carried by the guide. At about midnight they arrived at the farmhouse where a light meal was already prepared. At the farmhouse they were passed onto a Basque named Florantino who was to guide them across the frontier. He looked astonishingly fit and agile, although he was at least 45 years old. They learned later that he was a professional smuggler, wanted equally by both the French and the Spanish police. His assistance to the Allied aircrews undoubtedly would have added his name to the Germans 'Wanted' list as well. Refreshed by their meal they once more moved into the darkness wiht Florantino setting a cracking pace. They followed a rough mountain trail with prickly plants like gorse lining the edges. As their legs brushed the plants the prickles penetrated their thin trousers and scored their shins. Wally considered the terrain suitable only for the wildest of Scottish Highlanders. Later examination of his shins made him think what an inverted porcupine might do.

The first mountain pass on the French side was less steep than he expected and after following the mountain paths and sheep runs, through woods, they came to some flat ground at about 3:30 a.m. On the far side was the river which marked the fronrier. Caution was still a key-word, while Florantino carried out a reconnaissance. All was clear and he led the way to a shallow but fast flowing part of the river, about 30 yards across, which they successfully waded. Florantino held the arms of Doug, the American, and Alf, whilst Wally found a six foot pole a useful aid. he steadied himself with it by placing the end in the rived bed on his down stream side as he waded across. Their elation on reaching the far side was naturally boundless, but was tempered still with caution. The Spanish patrols were not noted for their friendliness, and there was always the danger fo being betrayed and returned to the French side of the frontier. Wally calculated that it was exactly 50 days, almost to the hour, since he and hsi crew bailed out of their Halifax aircraft.

The Spanish Evasion

They quickly left the river bank and climbed up a hillside through dense undergrowth to a railway line. Here they turned left, following in Indian file, using the faces of their luminous watches as a guide in the pitch darkness. Suddenly there was a crashing sound, followed by the breaking of bushes. The bombardier Alf, had missed his footing in the dark on the uneven track and fell some ten feet down the slope. They helped him back onto the track and carried on walking hoping that the noise had not aroused any untoward attention. The southside of the railroad track appeared to be flanked by a sheer wall. They lost touch with their basque guide Florantino, but a whisper comming several feet above them revealed his presence. He was standing on a ledge and they climbed up to join him. After a further short climb they came to a road which they crossed over. They then made a direct climb up the steep mountainside, which was extremely arduous and lasted until daybreak. High up amongst the mountains they came to a plateau on which was a road made by general Franco's prisioners of war. They continued on until the landscape gradually eased into the more welcome sight of farmland, and Wally spotted some inviting cherry trees. The fruit was ripe, and he was unable to resist the temptation of stripping a few handfuls, which he thought were the finest he had ever tasted. Little did he realize that four years later he would be flying plane-loads of the same fruit to London markets.

They reached a small farm house where Florantino announced that they had arrived at the end of his 'safety zone', so they decided to split up. Doug and Alf would rest awhile with Florantino in the farmhouse, whilst Wally would continue his journey with Franco as his guide. They hurried on as Franco was anxious to reach San Sebastian during the workers rush hour, which would give them adequate cover. They came into the town of Irun and eventually to a tram terminus. Franco told Wally to board the tram and stay in the rear and keep quiet, while he would be in the front. He bought two tickets, handing one to Wally. It was a hazardous ride, jolting their way, mile upon mile to San Sebastian. At length Franco got off the tram, followed by ally, and they walked separately until they arrived at a house near the sea-front. They recieved a very warm welcome; Wally stepped himself in a hot bath and then sat down for a fantastic meal. The Spanish housewife was a marvellous cook. The meal was preceeded by a couple of glasses of Anis, the local liquer, a most enjoyable and warming aperitif. After the meal Wally was ready for some much needed sleep.

That evening Franco returned to Irun to contact Alf and Doug and bring them by the same route to the house. On the fourth day of their stay they received a message that they were to be taken to Madrid in a limousine. This was sent to a rendvous by the British Counsel and it arrived at 10 p.m. that evening. They had already made their farewells to their host and hostess and their guide, Franco. Wally learned later that Franco was now living in the U.S.A and had become a priest.

The journey by limousine was a long one; they arived in Madrid at breakfast time on the 10th of June 1943. At the British Embassy they could really relax at last, whilst documents were prepared for their return to the U.K. via Gilbraltar. Meantime the Air Ministry informed Wallys wife Betty, that he had arrived safely in a neutral; country. The information was strictly confidential and should not be divulged. Much as she wanted to, Betty did not even tell her parents with whom she was staying at the tim, until some ten days later, when Wally's letter arrived from the Embassy in madrid. They recognized his handwriting on the envelope. At the Embassy Wally joined up with sic other evaders - American, Canadian as well as British. Three of them had unfortunately spent a few unpleasent weeks in a Barcelona jail. Whilst staying in the British Embassy Wally suffered from the delayed effects of a back injury, a slipped disc, which was later attributed to his landing following his parachute descent. He was thankful that the pain which was now becomming intense had not occured earlier. The train journey to Gilbralter, which took nearly 24 hours played 'merry hell' with his back injury. The U.S.A.F. officer Doug, was nearly caught by the Spanish customs. It appears that all evaders of what ever nationality, going through Gibralter had to be 'British'. When Doug was asked by the Spanish custoims officer to name his place of birth he replied: 'Canterbury'. Teh next question was 'What country?' Doug replied Yorkshire!. His exit document was thus solemnly completed.

While at Gibralter Wally was able to obtain the services at the sick quareters of a excellent masseur who relieved much of his back pain. Unfortunately the pain caused by this type of injury seems to recur, and Wally is now in the receipt of a disability pension in compensation. Wally was also the victim of a pay analomy which was notified to him on his return to the U.K. At the time his aircraft was shot down he help the rank of Acting Squadron leader, and was paid accordingly. The pay continued at that rate until he crossed into British territory at Gibralter. He found that he was now demoted to his substantive rank of flight Lieutenant, and paid as such, on the grounds that he was no longer 'filling a squadron leader vacancy'. His former rank of Squadron Leader was not restored until his return to flying duties, following on from his survivors leave. At Gilbralter he was delighted to hear that two additional members of his crew, his navigator - F.Off Osborne and his wireless operator Sgt Laws, had already passed through there for the U.K. he himself arrived by Dakota  on June 22nd 1943. Following a "debriefing" in London and the issue of travel warrants, he 'escaped' to Yorkshire for 'survivors leave' where he was able to meet his wife Betty (summoned by telegram), and many friends from 102 Squadron at Pocklington and from Dishforth where they had previously lived. It was in Yorkshire, at Topcliffe, that Wally was informed that he had been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

on June 22nd 1943. Following a "debriefing" in London and the issue of travel warrants, he 'escaped' to Yorkshire for 'survivors leave' where he was able to meet his wife Betty (summoned by telegram), and many friends from 102 Squadron at Pocklington and from Dishforth where they had previously lived. It was in Yorkshire, at Topcliffe, that Wally was informed that he had been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Wally's wife had expected an emaciated near-corpse for a husband. She was agreeably surprised to greet him looking so bronzed from his temporary sojurn in the Mediterranean sun.

From Christopher Longs Web page on the Pat Line

The Escape & Evasion lines – which grew spontaneously to assist Allied servicemen and agents who had escaped from German arrest, prisons and camps or who were evading capture. These lines were usually founded by civilians in France (les passeurs) and then adopted and supported by MI9. They included: 'Pat', 'Comet', 'Shelburne', 'Burgundy', etc. and were normally led by trained MI9 officers, couriers, radio operators, etc. Their instructions from London, often came via coded messages in BBC radio transmissions and in the BBC's 'personal messages' – e.g. the 'Alphonse doit rester' message indicating to Pat O'Leary that he should stay to develop the Acropolis line. The first officer sent to develop such freelance lines was Donald Darling, an MI6 officer 'loaned' to MI9 and based in Portugal (a ploy by MI6 which regarded the later as a threat to its own operations.) An Escaper was a person who had been captured vs the Evader who was on the run trying to avoid capture. Sherri Ottis who has written a thesis on this subject provided the AAF airman Doug's last name of Hoehn. I'll try to locate him for this profile as well. In addition it turns out that Wally and his group were amoung the last to escape from this route as it was betrayed soon after their escape.

Upon returning to England he was awarded the DFC, Distinguished Flying Cross again at the hands of King George V The DFC is the companion medal to the DFM won as a sargent pilot. [ note: NCO pilots like sergeants could win a DFM but not a DFC. Officer Pilots could win a DFC but not a DFM. Wally won both in his career. A second award of either would have resulted in a "Bar" to either award similar to a U.S. Oakleaf cluster]

Evaders as escapees were called could no longer go on operation over the continent for fear that if shot down again they especially may be targets for tough interogation to reveal the escape route and individuals who helped them in occupied territories. Wally was assigned to the Empire Flying School in August of 1943 at Hullavington as Flight Commander "handling Squadron" In this capacity he tested and assisted in testing all types of aircraft then in use. Compiling flight characteristics, amending "notes" as needed, eventually he took over the squadron with his rank of Squadron Leader being restored. In 1945 he was awarded the Airforce Cross for work carried out as a test pilot. The award was presented by the Air Vice Marshall. With the end of the war and reduction in RAF compliment Wall retired in November of 1946. His formal end to a military career had seen him accumulate 3169 hours of flight time in 128 different aircraft.

His civilian career was that of Airline pilot as his experience as a test pilot, large number of hours and four engined experience prepared him well for the role. He worked for Scottish Avaition and later with Lancashire Aircraft Corporation (later Skyways Limited) as Chief Pilot. During his tenure there he was recalled to participate in the Berlin Airlift where we had the responsibility to operate 24 aircraft for the company. For his work during the Airlift he was granted a Coronation Medal. From 1949-50 he participated in the National Air races. Winner of the "Air League Challenge Cup " and fourth place in the Kings Cup. His civilian career took him from Bermuda to Buenos Aries to Iceland and India.

His daughter Sylvia remembers some of her fathers trips. Sylvia: "I wasn't born till after the war, so I have no memories of it, although I do remember rationing as it continued in Britain until the early 50's. Sugar and some other staples were rationed, and we had ration cards. Fruit was scarce, and my father would occasionally bring us oranges and grapefruit from the middle-east when he had flights there."

Whilst on an Airfield in Jamaica his Avro York Airliner  was sabotaged. Someone had stuffed grass in the pitot tube of his aircraft rendering the airspeed indicators inoperative and altimiters. The evidence of this would not become apparent until airborne. Wally took off into the night and without the use of these essential instruments, he never the less flew the aircraft to Bermuda some 1450 airmiles, where he landed safely. His civilian career added a further 3000 hours to his log. Due to family illness he was forced to retire in 1953 from Civilian Avaition. His final total flying hours stood at 6255.

was sabotaged. Someone had stuffed grass in the pitot tube of his aircraft rendering the airspeed indicators inoperative and altimiters. The evidence of this would not become apparent until airborne. Wally took off into the night and without the use of these essential instruments, he never the less flew the aircraft to Bermuda some 1450 airmiles, where he landed safely. His civilian career added a further 3000 hours to his log. Due to family illness he was forced to retire in 1953 from Civilian Avaition. His final total flying hours stood at 6255.

In 1963 he joined the Territorial Association as captain Administrative Officer. As Acting Major he was transferred as Assistant Secretary to the Ayrshire Territorial Association HQ.

In April of 1975 Wally was awarded the CADET FORCES MEDAL. for his service with Ayrshire Army cadet force from April 1963 to April 1978. During this time he was the Sports Convener for the Lowlands and helped promote sports generally throughout the Army Cadet Force in Scotland.

In order of Priority the medals are MBE, DFC, AFC, DFM. Squadron Leader Lashbrook was awarded the DFC the DFM and the AFC for wartime service and The MBE in 1978 presented by Queen Elizabeth II. as well as several other campaign decorations.

The Order of the Decorations Above

Distinguished Flying Cross Awarded to officers and Warrant Officers for an act or acts of valour, courage, or devotion to duty performed whilst flying in active operations against the enemy.

Distinguished Flying Medal Awarded to non-commissioned officers and men for an act or acts of valour, courage or devotion to duty performed whilst flying in active operations against the enemy.

Air Force Cross Awarded to officers and Warrant Officers for an act or acts of valour, courage, or devotion to duty performed whilst flying, but not while in active operations against the enemy.

British Empire Medal Awarded for meritorious service which warranted such a mark of royal appreciation.

Wally retired in 1978 from what he refers to as active work. He assists with the local Youth Organizations in the meantime and recieves letters from people around the world. At least two of his crew are still with us and I will try to include more about them in this profile.

Links

BACK to MAIN PAGEBack To Main Page

RAF Knights Another site dedicated to individuals with P.O Prune references through out.

RAF Knights Another site dedicated to individuals with P.O Prune references through out.

Larry Wright's RAF Bomber Command - Outstanding site source of crests/photos source.

Larry Wright's RAF Bomber Command - Outstanding site source of crests/photos source.

Chris Longs Pat Line.Site on WWII Evasion routes

Chris Longs Pat Line.Site on WWII Evasion routes

A Belgian Family's Story helping Evaders and the heavy price they paid

A Belgian Family's Story helping Evaders and the heavy price they paid

Daniel Greens WWII Airpower Page

Daniel Greens WWII Airpower Page

Canadian AirAces Home Page

Canadian AirAces Home Page

Society of Bomber Command Historians

Society of Bomber Command Historians

Halifax Appreciation Society

Halifax Appreciation Society

Canadians Veterans Affairs Site (Decorations Source)

Canadians Veterans Affairs Site (Decorations Source)

RAF Station Marham site

RAF Station Marham site

SOME BOOKS ON BOMBER COMMAND

This page hosted by

Get your own Free Home Page

.

. .

.

work in progress

work in progress

..

..

MOTTO - BEFORE THE DAWN

MOTTO - BEFORE THE DAWN

..

.. It was in a Bristol Blenheim marked with the Finnish Rosen Cross (Straight Swastika) that Wally was first "blooded" by antiaircraft fire. Not by the enemys but by his own. He was ferrying the aircraft straight fromt he factory in Bristol to Liverpool for shipment to the Finnish airforce. The aircraft had been painted with the Finnish national insignia on the wings and rudder. This symbol was mistaken by the gunners at Cheltenham for Nazi symbols and there were several near misses. The gunners thought they were firing at a German JU88.

It was in a Bristol Blenheim marked with the Finnish Rosen Cross (Straight Swastika) that Wally was first "blooded" by antiaircraft fire. Not by the enemys but by his own. He was ferrying the aircraft straight fromt he factory in Bristol to Liverpool for shipment to the Finnish airforce. The aircraft had been painted with the Finnish national insignia on the wings and rudder. This symbol was mistaken by the gunners at Cheltenham for Nazi symbols and there were several near misses. The gunners thought they were firing at a German JU88.  His hours had grown to 1040 at this time and shortly after this the RAF Ferry Pools were disbanded. The duties were then handed over to civilian pilots known as the Air Transport Auxiliary.

His hours had grown to 1040 at this time and shortly after this the RAF Ferry Pools were disbanded. The duties were then handed over to civilian pilots known as the Air Transport Auxiliary.

On the return to Dishforth by the main party, Wallys wife Betty, who was living in the nearby village, on hearing the drone of aircraft naturally expected to see her hsband within an hour or so after their debeiefing. Instead, however, of being greeted by her husband, there appeared two of his fellow pilots carrying Wallys kitbag. Bettys anxiety was soon allayed on finding thet the kit-bag contained oranges, lemons and other goodies that were very hard to find in wartime England and not Wallys personal effects. The two pilots were able to assure her the her husband was merely delayed, and would be on her doorstep in a few days time.