John Henderson, owner of the Feel Good All Over record label in Chicago, heard the girlysound tapes and was intrigued. Soon Phair moved into his apartment

John Henderson: "Typically, she'd write a song and play it for me and it would be there, entirely. She had such a weird way of playing guitar, because she was trying to incorporate everything that one would hear in a fully produced record. It was percussive and melodic at the same time."

Henderson would bring in producer Brad Wood to assist in fleshing out the 4-track demos into fully formed ideas. But when Henderson and Phair tried to re-create that feel in the studio with Wood, they floundered. Henderson and Phair soon began quarreling about what direction to take: He wanted a stripped-down but precise sound, possibly with outside musicians; she wanted to rock, on her own idiosyncratic terms. "We both wanted something for me," Phair says. "He was projecting onto me what he wanted my music to come out like, which was wrong. So I blew him off."

Henderson was the first member of the music community to find out how tough and stubborn Phair could be. He became so disgusted by what he saw as the musical compromises she was making that he stopped showing up at the studio; Phair moved out of his apartment and began working with Wood exclusively on the music that would become "Exile in Guyville."

John Henderson: "I'm reminded of the famous Greil Marcus quote about Rod Stewart, something about how he wanted to be a rock star and all that entailed-sitting by the pool, having sex with groupies and snorting coke-and if he had to write great songs to do it, he was perfectly willing to write them. I think she betrayed her talent in much the same way. The relationship between Liz and me had become so strained that I realized it wouldn't last long enough for the album to be any good. So I figured why not let somebody else do it."

Chris Brokaw: ---initially i wasn't really crazy about Guyville. i loved the starkness of the girlysound tapes, and thought that that was the best and strongest vehicle for those songs. i also didn;t have much taste for pop music, at the time, and so the popification of many of those songs left me cold. i also was bummed that several tunes, such as "girlsgirlsgirls", had been these long, almost dylan-esque epics on the girlysound tapes, and then cut down to more sort of bite-sized tunes on Guyville. i really did think that liz was selling herself short. i understood what she was trying to do, i just didn't necessarily agree with it. fortunately for her, everyone else did, so... i listened to Guyville recently and really enjoyed it. it's an amazingly well-crafted album.

Henderson nonetheless tipped off Brad Wood that Matador was interested in Phair's music based on the "Girly Sound" tapes.

Super Producer Brad Wood

Brad Wood was born in Rockford Illinois into a surburban, upper middle class family. The Wood family business would be in Funeral Homes, a business passed down from Wood's great-grandfather to his grandfather to his own father.

Brad Wood: "For a while, it was extremely lucrative. But for most of my adolescence I've seen his money slowly vanish. Demographics control where you're buried, and Rockford's shrinking pool of Waspy Presbyterians means a shortage of stiffs."

Brad Wood founded Idful Music in 1988. Its location on Damen Avenue in Wicker Park played a huge role in that neighborhood's well-publicized transformation from immigrant launching pad to hipster terrarium. Working a hundred hours most weeks, Wood earned a reputation as a team player, and the fact that he looked just like his Ramen-eating clients helped. His going rate was whatever the band could afford and he learned the art of recording as he went. He mostly recorded the kind of tough-guy, wallet-on-chain, one-word-name bands for which Chicago isn't famous -- Tar, Table, Tool.

Brad Wood: "I own 2/3 of Idful and a partner owns the rest. I bought out a third partner, Brian Deck (drummer for subtly named Chicago grunge band Red Red Meat). We built Idful for less than $60,000 in 1988. Another $10,000 or so invested through 1993, then I plowed another 70 grand into it. We deliberately built Idful to be a facility that worked well for whoever was using it. So the irony's not lost on Wood that his commercial breakthrough came via a shy, decidedly non-Wicker-Park female singer-songwriter. Wood produced, played drums and bass, wrote and sang most of the harmonies on Liz Phair's debut album, "Exile in Guyville."

Brad Wood: "A lot of the four-track stuff is an extremely frank assessment of men and relationships. I had never heard anybody say those words, let alone sing them. Until I heard her music, I had wondered if there was anyone who really thought that way. I wished I had a girlfriend who was that cool -- though that would be kind of scary."

Brad Wood: "John Henderson introduced us. He runs a label in Chicago called Feel Good All Over. Originally her recordings were supposed to come out on that label and he was co-producing it with Liz and me. We started recording, and things didn't work out so well with John in that capacity, so it fizzled out and we did nothing for while.

Stylistically, the early sessions seemed unfocused and more traditional sounding (to my ears). John had a notion of how he wanted things to sound &, frankly, I didn't like it. As far as "working relationships", I recall not liking the chemistry between Liz, John & myself. Its no coincidence that I haven't spoken to John in ages. Working with Casey was a big improvement: he is a musician, for starters & we were pretty much on the same wavelength when it came to getting sounds.

Later, I called her up and we started recording again, just she and I. We did two or three evenings of recording just for fun where we tried to discover something. We recorded "Fuck and Run," and that's when I realized we were on to something. This really spare beat: just guitar, drums and vocals. It was right: simple, driving, direct & blunt. It had so much exuberance. I love that song. That particular recording is the epitome of what I was trying to capture. That was recorded so simply, just one microphone on the drums. It was the night that Liz & I finally got something recorded that made us both dance around & sweat. It happened quickly & pretty effortlessly, in between PBS shows on channel 11. I was glad that the new version was so different from the Girlysound tapes- such dark lyrics tied to such a happy beat. I liked the contrast..."

Brad Wood: Making Exile was a breeze, once the logistics were simplified. Liz had moved to her parent's house, making for a long commute to the studio. It was slow going, since recording had to be squeezed in around my work schedule at the studio and as a janitor. When Matador signed Liz, she sublet an apartment close to the studio & we established a good work pace. There was no thought given to sales at the time.

Brad Wood: The early sessions were mostly misfires, with only one song, Johnny Sunshine making the record (I think). Since most of the songs were built from the guitar and vocal, anything that didn't sound right was discarded. Mesmerizing took a few tries to get the percussion right, but most of the songs had a long time to develop, due to the time constraints in 1992 (see above). We would do a lot of thinking in between sessions...

Casey Rice: We basically all sat around and thought about how to make the guitar and vocals versions of the songs into what we thought would be better ones. Listen to her four track versions of the tunes, and try to come up with ways of doing them as a 'band'. I do recall there being no lack of candor and if someone wanted to do something, we tried it. If it sucked, no one would hesitate to say so if they believed it.

Narrator: It was during this time that Liz ingratiated herself in the vintage Wicker Park scene, becoming friendly with producer Brad Wood, Tortoise drummer John Herndon, comic artist and guitarist Archer Prewitt, Rainbo Club manager Jim Gerbe, Jesus Lizard front man David Yow, and engineer Casey Rice as well as various members of Urge Overkill and Material Issue. Days were spent in Idful and nights on the town were spent in Wicker Parker staples like The Double Door, The Lounge Ax, and especially the Rainbo Club.

Liz Phair: I was racing around, it was like this point in my life when I was trying hardest to be like the Shirley MacLaine of the Rat Pack. Y'know what I mean? I was working pretty hard on that. I wanted to know all the coolest people in the neighborhood and I wanted to be someone at the bar that people would want to talk to. My imagination was running overtime at that point so I was really into the whole "scene."

Liz Phair: Then, when I called Matador, they had already heard of it and were like, "Sure, go ahead and record an album for us. Great.�

Gerard Cosloy, Co-President of Matador Records: "I think it was sometime late last spring or early last summer (of 92). Liz called on the phone and asked if we'd put out her record. I get a lot of silly, audacious calls. But the day before, I'd read a review of a Girly Sound cassette in Chemical Imbalance(a punk fanzine). The review was very funny. It was just weird because Liz called that very day and wanted to know if we would put out a single and that was a little presumptuous 'cause we had never even heard anything of hers before." (Phair sent a six-song tape.) "The songs were amazing. It was a fairly primitive recording, especially compared to the resulting album. The songs were really smart, really funny, and really harrowing, sometimes all at the same time. I liked it a lot and played it for everybody else. We usually don't sign people we haven't met, or heard other records by, or seen as performers. But I had a hunch, and I called her back and said O.K."

Cosloy offered a $3,000 advance, and Phair began working on a single, which turned into the 18 songs of Exile in Guyville.

Liz's coming out party would come at the Lounge Ax in Chicago in January of 1993. this would be the first time many in the press and larger Chicago media and society would here the name which would become so ubiqitous over the next few years.

Greg Kot of the Chicago Tribune describes the night: She was virtually unknown outside of Wicker Park, her music still a private affair. But when advance tapes of "Exile in Guyville" began snaking down the local rock grapevine, the buzz brought a big crowd to Lounge Ax on Lincoln Avenue one Saturday in January 1993. At the bar next door that night, Phair was sipping tea at a table in back. Stuffed into an oversized coat, a red scarf around her neck, she looked even more waifish than her 5-foot-2-inch frame would suggest. At one point she shivered and leaned forward, gripping her stomach. "It's nerves," Phair explained. "I hate going up there." "Up there" is the modest stage at Lounge Ax. A half-hour later, she was singing and playing guitar before an audience of paying customers for maybe the sixth time in her life, and it would be an ordeal. She refused to make eye contact with anyone or anything except the "exit" sign, and her amplifier kept breaking down in the middle of songs. Then a string snapped, and Phair looked at her damaged guitar the same way a child might size up a three-legged dog. Finally, she glanced pleadingly at the sound board, and the technician behind it snaked through the crowd to perform equipment surgery. Phair soldiered on, and after 25 minutes, the set-much to everyone's relief-ended. The songs that night at Lounge Ax were even more riveting as heard on "Exile in Guyville," released a few months later on the New York-based independant label Matador.

Liz Phair: An opportunity just came along -- someone said I could make an album, and would pay for it, so hell, yes. When I made the album, everyone that I needed to prove something to was within a mile radius of my apartment. Not that many people were supposed to see it. I expected to sell about 3,000 records, and it would be in the indie crowd already, so what would it matter? It's already a self-selecting group of people who were not so prurient to begin with.

When I made that album, I had in mind, literally, like a handful of people that I thought would hear it and that mattered to me. And if you can imagine this, I was out of school and thinking I was going to be a visual artist and the whole music thing was kind of like a social setting for me. I knew about indie-labels and stuff and I kept saying, "This is going to do very well. People are going to really catch hold of this." In my mind I was thinking a thousand, twelve-hundred people. So it was definitely more about trying to be cool and ballsy and up to the boys than it was about trying to shock anybody.

The people who had known me my whole life were really shocked, because they didn't know about this post-collegiate stint that I was doing downtown, trying to be like, "rock girl." And that was probably the biggest shock to people who had known me through school and stuff. The reinvention of myself. And then people in the music scene -- that's what the whole point of Guyville was -- were shocked that I could make songs, or have intelligent lyrics. I wanted them to be embarrassed for all the nights they sat around, lording over the conversation, talking about music, never including me, and never really asking my opinion.

Liz Phair: The term 'Guyville' comes from a song of the same name by Urge Overkill. For me, Guyville is a concept that combines the smalltown mentality of a 500-person Knawbone, Ky.-type town with the Wicker Park indie music scene in Chicago, plus the isolation of every place I've lived in, from Cincinnati to Winnetka. In Oberlin there was a Guyville. In New York there's a Guyville. In San Francisco, there's a Guyville. I didn't happen to live in it there.

All the guys have short, cropped hair, John Lennon glasses, flannel shirts, unpretentiously worn, not as a grunge statement. Work boots. It was a state of mind and / or neighborhood that I was living in. Guyville, because it was definitely their sensibilities that held the aesthetic, you know what I mean? It was sort of guy things - comic books with really disfigured, screwed-up people in them, this sort of like constant love of social aberration. You know what I mean? This kind of guy mentality, you know, where men are men and women are learning.

(Guyville guys) always dominated the stereo like it was their music. They'd talk about it, and I would just sit on the sidelines. Until finally, I just thought, '[screw] it. I'm gonna record my songs and kick their [butt].' (Listen to a .wav clip of Liz discussing what guville is here)

I grew up as a girl unheard by the boys -- at dinner tables the men would speak mostly, and their opinions were taken seriously. I felt the patriarchy through that. I felt it at school as I got to a certain age. The guys would be like, "You don't know anything, you're a stupid girl," because my interests were different. When I got to college, then it was all, "You don't know anything about music." I made that whole album [Guyville] because they thought I knew nothing about music, and I was like, "You don't have to fucking know the genealogy of a band to know something about music."

I shouldn't say this -- my managers told me not to say this -- but a lot of Guyville is bullshit, total made-up fantasy crap. That stuff didn't happen to me, and that's what made writing it interesting. I wasn't connecting with my friends. I wasn't connecting with relationships. I was in love with people who couldn't care less about me. I was yearning to be part of a scene. I was in a posing kind of mode, yearning to have things happen for me that weren't happening. So I wanted to make it seem real and convincing. I wrote the whole album for a couple people to see and know me.

What I think made that album (Exile) so special is that I came out of nowhere and that I went insane writing that. I had all this passion, which was the sole focus in my life. Plus, I was getting stoned all the time, living a bohemian life. It was like a real madness and it's kind of psychotic, but because I couldn't talk to this man anymore, I decided that Mick's voice would be his voice and I could explain my side of the relationship to him. So I always wonder if I could make that big of a splash now because I'm not willing to sacrifice my life for a piece of art that way -- and that bothers me. That will keep me up at night because I know that I won't go to the edge like that anymore. And sometimes going to the edge like that is what makes those really powerful punches to music.

It created this whole bedroom environment, this fantasy world that no one knew a girl like me would have.... it was (shocking) because the girl next door... was suddenly pretty much showing her pussy."

Liz: The Stones were always the band for me -- forget art, forget quality, forget the whole thing -- they just do it for me. I get a pleasurable feeling between the ribs and the knees -- and I'm not speaking sexually -- when I listen to them. You get that stomach crunch.

I was sitting with a boyfriend talking about how I wanted to use a template, because I didn't know how to make a rock album. A friend told me that he said I should put out a second album concurrent with my first. But I thought he meant I should do a double album. And I was like, 'Hey, that's a good idea.' But then I was sitting around my apartment thinking like, 'What's a good double album?' because I don't really buy records. I was sifting through tapes that a friend had left in the apartment, and I picked up Exile On Main Street, and I didn't even know it. I was like, 'Is this a good one? Was this a commercial success? Did people like this one?' It was sheer luck, that I picked Exile On Main Street out of the box. It could have been, like... Neil Diamond. And there was Exile and I'm like, 'That's the one'. It was just kind of honestly like a lightning bolt. It gripped me. It was one of those things you couldn't really explain in any rational sense. And the more I listened to it, the more it was perfectly appropriate. I really just spent a month or so listening to it nonstop everywhere I went, and I began to organize my songs in a correspondence with themes I'd seen in Exile. (Listen to a .wav clip of Liz confirming the link beteen Exile on Mainstreet and Exile in Guyville here)

I thought of Exile on Main Street as a big, long love letter -- a good love letter. Not just, 'Oh, Lord, I need you,' but living with your wants, desires, limitations, self-destructive habits and whatever other elements are sparked when you feel connected to a person. I wanted Guyville to be my equivalent of the Rolling Stones' Exile on Main Street -- something classic.

| Exile on Main Street | Exile in Guyville |

| 1. Rocks Off 2. Rip This Joint 3. Shake Your Hips 4. Casino Boogie 5. Tumbling Dice 6. Sweet Virginia 7. Torn And Frayed 8. Sweet Black Angel 9. Loving Cup 10. Happy 11. Turd On The Run 12. Ventilator Blues 13. I Just Want To See His Face 14. Let It Loose 15. All Down The Line 16. Stop Breaking Down 17. Shine A Light 18. Soul Survivor |

1. 6 foot 1in. 2. Help Me Mary 3. Glory 4. Dance Of The Seven Veils 5. Never Said 6. Soap Star Joe 7. Explain It To Me 8. Canary 9. Mesmerizing 10. Fuck And Run 11. Girls! Girls! Girls! 12. Divorce Song 13. Shatter 14. Flower 15. Johnny Sunshine 16. Gunshy 17. Stratford-On-Guy 18. Strange Loop |

I fixed on the Rolling Stones' Exile on Main Street and treated it like a thesis, compiling the songs I'd written years before I ever heard that Stones album, which worked best as coincident parallels. I thought it was a cool structural device, and I wanted to give myself something extra to think about. I come from an academic background, and I got off on going through my little warehouse of songs to find the ones that I thought had the same feel, were of the same type. The more I listened to [Exile On Main Street], the more it was perfectly appropriate. I began to organize my songs into a correspondence with themes I'd seen in Exile (including sequencing her 18 songs in five-four-five-four thematic chunks just as the Stones did on their 1972 double album). I made lists and lists of what Exile's songs were -- three words or less, what kind of song is this? -- and made tons of sequence lists, different orders of the songs I wanted to do. It was like writing a thesis, talking a song of mine and somehow putting it in a dialogue with a song on Exile, both sonically and lyrically. You can hear what '6'1"' is about if you listen to 'Rocks Off' and then you listen to '6'1"' and then you think about it. Just as the lyrics and then the guitar parts on Exile On Main Street lead you to an impression rather than an actual image, in my songs -- and in the juxtaposition and sequencing -- I tried to do the same thing."

What I did was go through [the Stones' album] song by song. I took the same situation, placed myself in the question, and answered the question. 'Rocks Off' -- my answer to that is 'Six Foot One'. It's taking the part of the woman that Mick's run into on the street. 'Let It Loose' -- okay, that's about this woman who comes into the bar, she's got some new guy on her arm, Mick was in love with her. He's watching this guy, 'eh, just wait, she's gonna knock you down.' He's talking, 'let it loose,' as if to be like, babe, what the hell happened, talk to me. So my answer was, 'I want to be you...' (Phair sings the opening to "Flower"). I put a song in there that lets it loose.

I absolutely took it dead seriously. I sat around with stacks, like hundreds of pieces of paper -- you have to remember, I was stoned a lot. I was a twentysomething no-job. I hung out playing guitar all day. I had all this education, I thought analytically and someone had made a dare. I think an ex-boyfriend was like, "Well, why don't you do a double album? Why don't you do Exile On Main Street?" And it fit perfectly with what I was pissed about at that time: that no one thought that I could do anything of any value in the musical sense. So I just thought the bigger the mountain, the more motivation I had to climb it. I still have that problem. I had little symbols, each song would be listed, and I would do the songs on Exile, the one with the little symbols next to them, there was one with a kind of asterik, I can't remember. That was a pop song, and then a long, wavy line meant a slow song, a cross was another kind of song, a rocker was diagonal lines sort of like on Charlie Brown's shirt. The symbols went so far as to be both in terms of musical style and also content, like if it was a depressing song about sorrow or angst or something, there was an arrow pointing from the top-left down to the bottom-right.

Yeah, I went nuts with it. I can't tell you. We would go into the studio, and I'd be like, "You have to have this big guitar solo three-quarters of the way through because that's what Exile On Main Street has." And the lyrics had to be an answer or my equivalent. It had to either be putting him in his place, like if he was talking about walking down the street, and he's talking about he's mister footloose and fancy free, doesn't meet anybody who gives a damn. I had to write a song about how much pain you could cause someone with that kind of attitude. Or I'd write my own song about walking down the street, being footloose and fancy free and not giving a damn. It either had to be the equivalent from a female point of view or it had to be an answer kind of admonishment, to let me tell you my side of the story. No wonder it's such a good album -- I put so much into it and uninterrupted attention, it was like a doctoral thesis

When I made Guyville, I was extremely frustrated, extremely... there was so much that I needed. The album was designed to say to this man what it had been like for me. It was like a real madness and it's kind of psychotic, but because I couldn't talk to this man anymore, I decided that Mick's voice would be his voice and I could explain my side of the relationship to him. (Listen to a .wav clip of Liz comparing 'Rip this Joint' from Mainstreet to 'Glory' from Guyvillehere)

Of course [the Stones'] positions were different. That album is about them dealing with their identities through the new eyes of their fame. Their album is far more musically expansive, intricate than mine. But I had to be true to my circumstances, when I'm a female singer-songwriter and I take a far more singer-songwriter approach to the structure."

It really isn't important to me to have done it, so I could learn what goes into a really great album. The structure gave me limitations. It gave me a universe within which to be as creative as possible because there were laws."

Brad Wood seemed intrigued when Liz suggested Main Street as a blue print and exile as a female answer to it.

Brad Wood: When she first brought it up, I was like 'Oh, really? You mean you can't get into that album like I do?'. Because it is a real guy thing. Her logic started to make sense. We didn't want it to sound like a retro record, and we didn't want it to sound real '90s. I wanted it to sound really personal, trademarked like the Stones record sounded, so that as soon as you heard a note off it, you said, 'That's the Rolling Stones.'

Narrator: Primary recording for Exile In Guyville took place in the summer of 1992 at Brad Wood's Idful Studio's in Chicago. Idful Studios was located on Damen Avenue in Wicker Park. The studio was a rented space in the strip mall. The studio itself was basically shoehorned into the location and was not the ideal set up for a studio; at Idful you had to walk through the live room to get to the john, and if someone was tracking, you just had to wait. The interior was a bit dour with nary a window in the place. Wood had, however, made a name for himself in the Chicago music scene by recording such artists as Tar, Tortoise, Table, and Tool at Idful. Idful's success was partfully responsible for the Wicker Park neighborhood's eventually becoming a hipster mecca. Brad was the majority owner of the studio. Through a mutual friend in the band Red Red Meat, Brad offered Casey Rice, local artist and musician, an engineering position at the studio.

Casey Rice moved to Chicago in the summer of 1988. "I came here to do visual art, not music," he says. "I sold all of my records." He'd studied political science and art off and on for several years at Ohio State University, while there playing guitar in a punk-rock band called Control and the art-punk outfit IDF. During his first year in Chicago, Rice mounted a show of paintings and several performance pieces. The following year he would returned to music, with a punk band called Dog.

Dog became the opening band of choice for other loud indie-rock acts. Rice befriended the movers and shakers of the early Wicker Park rock scene, including Precious Wax Drippings (with future Tortoise drummer John Herndon) and Friends of Betty (some of whom would go on to start Red Red Meat). When Red Red Meat drummer Brian Deck, who cofounded Idful studios with Brad Wood, pulled out of the business in 1992, Rice was offered an engineering position -- even though his resum� at the time consisted of one album for IDF and the first EP by Chicago punks Burnout. But he proved a quick study. "I was really interested in the physics of it," he says. "It was a chance to get paid doing something related to music instead of banging nails or painting houses. I had an interest in the job as a career for a while -- until I realized what it meant."

As it happened, when Rice took the job at Idful, Liz Phair was recording Exile in Guyville there. She had no band of her own, and since Rice could play guitar, he was drafted into service.

Brad, Casey, and Liz would provide the core musicians who performed on Exile in Guyville and Whipsmart. Along with bassist Leroy Bach they would also comprise Liz's touring band for much of 1993-94.

Most albums are built from the ground up, with the rhythm section recorded first and then the guitars and vocals layered on top. Wood worked backward, with the help of guitarist and engineer Casey Rice, structuring the drum patterns and bass lines around Phair's vocal phrases and guitar riffs.

Liz Phair: It was fun. Actually we just played our parts separately. I layed down the guitar, and then I would just tell them what kind of song it would be and what kinds of instruments we needed to do. And then they would go in there and figure out a part and then do it. It was more like collage work than really playing with a band. It was like... you know when you do those drawings and you do the first half and then... a collaborative effort!

Bassist Leroy Bach: People never talk about her guitar playing. But she's brilliant on guitar. The work that she puts into this shit is not discussed like someone else's work method might be discussed. She does a lot of normal things that famous guy musicians do, but that's not part of the Liz Phair conception.

Narrator: While Liz has tended to sway back and forth during her career over the influence that Brad Wood has had on her career, it is obvious from seeing how Exile and Whipsmart were put together that Brad Wood and Casey Rice were highly influential and instrumental in crafting the Liz Phair sound. Both EIG and WS were created sonically for the most part in the studio. The sound of these two albums were not fleshed out until they started working on them in the studio. Liz ran into problems with WCSE when she recorded with Scott Litt. Litt was a producer that was used to dealing with artistis that pretty much came to the table with their songs fully fleshed out and ready to go. Much of her lackluster work with scott litt can be attributed to her lack a producer that was able to help craft that songs in to a full scale song.

Wood: Nobody has ever really asked for that particular sound. The sound of that record was something that I'd been working on already. The drums were recorded with two microphones, sometimes three. I'd been reading magazine articles from years ago and checking out pictures from Zeppelin and from Beatles sessions, and trying to find microphones that might accomplish that sound. I had been working on some Seam stuff before Liz came in and that gave me some encouragement to try her record that way, especially when she came in with the idea of it as a response to the Stones.

Liz: I can't listen to Guyville, although I feel like I really got what I aimed for. It's just my voice, it's like, 'Oh, c'mon, hit that note! A little higher, higher!' When you're sitting in the studio with all your friends and your vocals are turned up way beyond the music, you try to smile blithely till your voice does some terribly hideous act.

Liz also took time during July of 92 to collaborate with local Chicago band Ashtray Boy. Liz performed on two tracks, "Shirley McLaine" and "Infidel", off of their album The Honeymoon Suite.

The cover that we have come to know for EIG wasn't the original design. In an inter with Lewis Largent on MTV's 120 minutes, Liz said that the original artwork was largley collaged based and involved a fat lady in a pool. After many statements from the record label that something like that wouldn't sell, the concept was rejected and may have inspired Liz to go for a more attention getting cover shot.

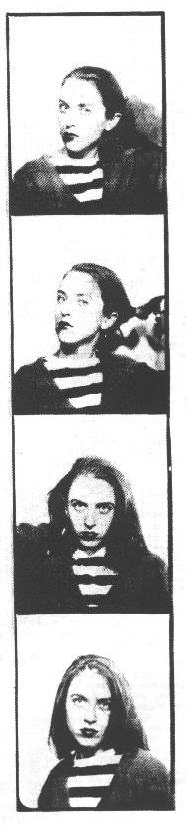

Liz Phair: (The album cover) was Nate Kato's (of Urge Overkill) idea. Put it this way, we were at the Rainbow taking pictures because I'm doing some sequences for my video of me singing into photo booth pictures mouthing various parts of the sentence, which we were going to like flip in. It sort of fully didn't come off so I'm going to probably do it in the next video. We're just going to stick in some now. But I've been doing this for months, going to the Rainbow and doing some more photo essays as I like to call them. And he got me to take my shirt off while I was doing this and I went back into the booth and I had my big coat on and stuff, and then I brought out the product and we were all just sitting around and he was like, "This is the album cover! This is the cover!" I don't know if you know him, but he has this brilliant sort of way of just being like, "This is absolutely...and this is so '90's! And we, Urge! If anyone knows what '90's are, Urge are!" I mean I don't think that is particularly true, but he cropped it, he said, "You have to crop it exactly like this!" He has an eye which I think is damn near genius, and he was showing me how to crop it and he cropped it all up for me and I thought that was really cool. But it was an after the fact thing. I had taken the picture, and he just decided that it would make a great album cover.

I took a lot of them that night and he liked this one a lot. He just pounced on it. He was like "This is the cover! Lizzy this is the cover!" He probably bought me a double scotch or something. It was really funny.

The nipple is still there, but just barely. He cropped it that way. That's Nate's cropping. I kept it exactly. He spent literally ten minutes showing me exactly where to crop it so it's like barely. I mean that's what's really tasteful about it. I'm topless, but it's really just a hint of it which is so much better. It's his cropping exactly. No, there was no concession made. That was exactly how we intended it.

It made sense to me because Exile In Guyville has that front back cover which I've been working with. Basically to do this album I've decided instead of...I hate when people hint that I might of ripped things off, they usually haven't heard it, or taken only the cover. It wasn't about ripping it off. A good thesis is to take the essence of any intent, and then to adapt it to what you're trying to do or to use an equivalency. And to me the whole (Rolling Stone's) Exile On Main Street cover having the freakshow on the front, and then having the band members on the back was really discussing the nature of performance and about where they were in their lives right then, having stumbled into fame and finding it. It's just a different world. we all know that, but until I experienced it I just didn't really get it. I didn't get what it does to your personal life, or how it changes you. It's like, you're living the same life, and yet you're not. It's a different place. It's very hard to explain. To me the freakshow wasn't about "aren't we freaks," it was really more about... those performers on the front when you do think about it are people who often made themselves into this thing, like performance artists, as were the Rolling Stones. They were very aware that they were kids from wherever, and that this was something that they had created, and it snowballed. And so to me to have on the cover me in this performance pose, and then on the back have me in my little home staring at the camera like, riiiight, is exactly the same thing. The Liz of the performance, when I go into my performance head, and me on the back just like right in the cameras face, like I want to do when I am myself. I'll just be like, ahh, come on! You know what I mean, like get over it! Like do you really think I walk around like looking like this? You know what I mean? Sort of like to poke fun at the fact that people totally believe this shit! People believe everything they're handed. It's intense! If they love these artists don't they understand they're artists? They're doing this for you! They're putting this on for you! Love them for that. Love them for their ability to entertain you. It's all about artifice and reality, and games people play.

There were several pieces od inside artwork that accompanied the Exile IN Guyville album. One piece elaborated on the joys and sorrows of andalusia with a cartoonish depiction of two dancers. This whole motif is based on the work of flamenco guitarist Luis Maravilla (Luis Lopez Tejera). The Joys and Sorrows of Andalusia is actually the title of a 1952 album by Lopez Tejera.

The interior artwork for exile in guyville is a direct lift from the artwork of Lopez Tejera's album, note the images below:

The Lopez Tejera piece is from either the back or interior artwork from the Joys and Sorrows album. Liz took guitar lessons as a teen and these flamenco recordings may have served as a early primer for Liz's burgeoning guitar skills. I imagine that Liz was paying a sort of homage to these lessons with her use of the Lopez Tejera motif. Another piece of the Guyville artwork was the Polaroid gallery:

The wording on the pictures is actually a paraphrase from the famous lines from Dirty Harry starring Clint Eastwood. The actual lines are:

Harry Callahan: I know what you're thinking. "Did he fire six shots or only five?" Well, to tell you the truth, in all this excitement I kind of lost track myself. But being as this is a .44 Magnum, the most powerful handgun in the world, and would blow your head clean off, you've got to ask yourself a question: Do I feel lucky? Well, do ya, punk?

There are also several salacious photos of a female that has a passing resemplance to Liz. The woman in question is actually Kristie Stevens, a local model in Chicago hired for the photos. One of the photos is of Brad and Casey horsing around during the recording of Guyville. The photos of of a fellow on the lighted sidewalk are actually Liz friend Shane Dubow, who was the inspiration for "Shane" off of Whipsmart and a buddy of liz during college and the years right after. The Gentleman in the Do You Feel Lucky? pick is Chicago scenester and Tortoise band member John Herndon. There are also a couple of childhood photos, one of which seems to be of Liz and her brother Phillip.

Liz had quite a time playing Exile for her parents for the first time:

My mother was mortified, mor-ti-fied. She doesn't see her little girl talking about sex. Mother is not an overtly sexual creature. She is very warm and beautiful and has probably enjoyed sex, but she did not talk about sex. It was not until the critical acclaim came that it was a piece of art that it was OK with my parents. Then they could hide behind the art part and be proud. "She cried because she said she had no idea I was so unhappy. I did not know what she meant. Now I listen to it and I think I was so unhappy, but I was also having some of the best times of my life -- the tail end of puberty. I was definitely a late bloomer.

Narrator: Liz Phair would receive widespread acclaim with the release of EIG. Along with PJ Harvey, Courtney Love, and Juliana Hatfield, Liz was hailed for ushering in a new era of female rockers. Exile in Guyville topped the Village Voice's 1993 rock critic's poll and was named album of the year by Spin magazine, while Liz was hailed by the editor of Billboard as "(leading) alternative rock's postpunk 90s naturalism to a captivating new pinnacle". Liz was cast in the role of sexual provocateur. Rock critics were falling all over themselves in heaping praise on EIG. The following from September/October 1993 Option magazine is just a sample of this:

..........And yet Guyville's bubbling emotionalism and carefully manipulated carnality quickly overshadow and ultimately render irrelevant the epic contextualization. (Lines like "I want to be your blowjob queen" and "I'm a real cunt in spring" tend to do that.) Pausing for this or that propulsive pop anthem ("Never Said") or lilting mood piece ("Stratford-on-Guy"), Phair delivers a lacerating recitation of romantic pathologies. To pull off the stunt, she has an impressive arsenal: extended metaphors (boys as unruly houseguests in "Help Me, Mary", love as a road trip in "Divorce Song"); an obsessive talent for diagnosing behavioral hiccups on the part of men ("6'1"), women ("Fuck And Run"), and the singer herself ("Girls! Girls! Girls!"); a distinctive and friendly gal-next-door style of guitar playing; and, not least, a malleable and protean voice that self-consciously toys with the unapologetic intellectualism of Joni Mitchell, the romantic depth of Christine McVie, and the rock credibility of Chrissie Hynde even as her straightforward delivery and piercing sincerity conveys an enormous emotional authority......

Heady stuff. Exile in Guyville would prove to hold up to such praise. It has almost universally been listed as one othe top 15 albums of the nineties and it was recently named by a VH1 panel of critics as one of the 100 best albums of All Time.

Wood: Well, the most changes happened working with Liz. That's been the most dramatic. Here's somebody who's never worked in a studio, and then she's on the cover of Rolling Stone. That's probably been the most dramatic by far, there's a lot of learning there, not all of it positive, but the vast majority of it really awesome. For instance, when we finished the record, Casey and I listened to it and thought, this is going to sell a lot of records. What, 5,000, 10,000, no probably like 30,000. 30,000 being a great ideal. And then it sold 300,000.

Exile was very much a suprise success. With an orginal marketing budget for the album of a miniscule $700, little was expected. The success of the album can be attributed to three major things. One, obviously, was the quality of the album itself. Second, was the widespread critical praise of the album that lead to excellent word of mouth for the album. Thirdly, Liz was more than happy to flak for the album.

Gerard Cosloy, Matador President: "If you had told me we were going to sell 5,000 copies, I would have been satisfied. If it had been 20,000 or 30,000, I would have been pretty shocked. There was no precedent for it in my experience. The sales were generated by a lot of word of mouth and by Liz's hard work."

Given her first flush of success and celebrity, liz was more than happy to play into it. Such willingness to buy into the big Music industry game often put her at odds with the insular chicago indie music scene.

Liz Phair: My music is good, people like to sing to my lyrics. They like the way that what I say makes them feel. It's humorful enough that people who feel uncomfortable with the more explicit stuff can let it in, and it's kind of rocking enough for people who don't listen to lyrics at all. I can speak articulately, and I'm cute enough that you can photograph me, and you can dress me up and I'll do it, I'll smile and I'll dance around. Of course, I'm gonna bust my ass marketing anything I do. It all comes in a whole big package. There are musical lifers who don't see it that way, to whom it's a sacred art form. But I've always been a slut in that sense..... This is also a business, and business is creative too. Damn straight I'm manipulating my career and the media. I don't mind treading the fine line between doing something interesting and valuable for society and totally just exploiting my popularity. I'm 27, I'm ready to cut my teeth on something. If it wasn't this, I'd be blasting into offices somewhere else wanting to get to the top of the corporation. It's ambition. Total, simple ambition.

Liz Phair: I don't really get what happened with Guyville. It was so normal, from my side of things. It was nothing remarkable, other than the fact that I'd completed a big project, but I'd done that before.... Being emotionally forthright was the most radical thing I did. And that was taken to mean something bigger in terms of women's roles in society and women's roles in music.... I just wanted people who thought I was not worth talking to, to listen to me.

I think at first I was really excited. I thought it was really pretty impressive in that I always read about people that kind of come out of nowhere and suddenly catch hold. But it wasn't something that I'd ever thought was coming down the road for me. I had all these other ideas, all these other visions of grandeur that had nothing to do with music and had nothing to do with that kind of popularity and notoriety and press. So it was really kind of exciting and like, "Wow, I must be special!" And then it became harder and it became confusing and I felt really alone and that I wasn't the one driving this thing anymore. I was just kind of dangling from the back. interview

Narrator: Liz's sudden success would also put her at odds with the Chicago scence from which she sprang.

Liz:"It's odd... Guyville was such a part of indie. But at the same time... I was kind of at war with indie when I made that record. It was kind of like a 'fuck off!' to all the indie people that I was around at the time. Nobody in my neighborhood liked me after the record came out.

Guyville was not a positive experience for me. "This was supposedly my greatest work and everyone now sort of uses it almost against me as when I was really good. I really felt very hunted."

"I remember quite a bit of bad local press. I was pretty controversial in Chicago (where she grew up), which was as big as the world was as far as I was concerned at that time.

I'd walk into bars and my friends would be debating... 'She dyes her hair blonde. She can't sing. She came from the suburbs'". They were so furious with me because I didn't deserve the attention I was getting. They had been slogging away in the city being indie for 10 years and I get out of school, throw this thing together and BOOM! I'm the poster child for indie.

(She recalls one night interrupting a heated debate between her friends at a bar.) "They shut up when I walked in," "I had this shocking realisation that they were arguing about whether Guyville was any good. "I was suddenly very self-conscious and mortified. I realised, too, that half of my friends were saying I shouldn't be successful."

It's (Indie) masquerading as independent � free from constraints of society � but is its own little constraining society. It's all about conformity within nonconformity, which to me is just (expletive deleted). Either you're free or you're not.

Liz Phair: Suddenly I realized this was like a phenomenon. And I had become representative of a thing. It was pretty clear that it boiled down to a relatively narrow understanding of what the whole album was about. And I felt what it feels like to be taken up in the national scene and given a label and used so writers could write about certain issues that they wanted to write about. I was an example.

Another problem that Liz would face during her popularity from Exile was performing her music live, something she almost dreaded.

Liz: I pictured myself in a lot of extremely adventurous situations when I was growing up, but I never pictured myself on stage. I'm still embarrassed to perform. I'm aware of my deficiencies and inexperience, and I can feel every eye that's out there. I feel apologetic, because what I sound like in my head, my vision of a song's potential, is sometimes so far from what I can convey, especially without a band.