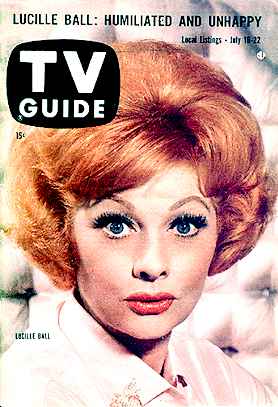

TV Guide

TV Guide

"A Visit With Lucille Ball"

July 18, 1960

Last Updated: July 29, 1997

Formatted by: Ted Nesi

Scanned and Provided by: Garth Arrik Jensen

By Dan Jenkins

On Jan. 19, 1953, Desi Arnaz rushed exulantly into the Hollywood Brown

Derby, grinning that wide, idiotic grin common to new fathers for the

past several eons. Striding down a side isle, he threw his arms

excitedly in the air and shouted, "Now we got everythin'!"

By "everythin'," Arnaz was encompassing quite a bit of territory -

an eight-pound son born that morning, the "birth" of the Ricardo son on

I Love Lucy that same night and a gold-plated peak of popularity for a

television series which, in all probability, will never again be

approached.

On May 4, 1960, just seven years later, Desi Arnaz and Lucille

Ball, quite possibly the most widely known couple in show-business

history, were divorced. She had sued for divorce once before (she didn't

complete the proceedings), but that was back in 1944 when Desi was a

corporal in the Army, Lucy was a star at MGM and World War II was

getting all the headlines. By 1960, the Lucy-Desi combine had made so

many headlines that no one even bothered to look at the press-clipping

scrapbooks any more, or the countless awards that had rolled in on them

from all over the country.

On an overcast spring afternoon, just 10 days after the divorce,

Lucille Ball was sitting in her small but tastefully decorated dressing

room on the Desilu lot. That morning, during a short drive over to the

neighboring Paramount lot to confer with the producers of her upcoming

picture with Bob Hope, she had stuck her head out the window of her

chauffeur-driven car and shouted to a friend, "Hi! Remember me? I used

to work at Desilu."

The remark was not only typical of Lucy Ball but an unwitting

reflection of her character and a classic off-the-cuff example of the

laugh-clown-laugh tradition. Like most true clowns, Lucy is not a

jovial, outgoing person. Her devastating sense of humor, often with a

cutting edge, is reserved for her friends. In her dealings with the

press she is precise, truthful - and sparing with words. A newsman asked

her recently if she had plans to marry again. Lucy stared at him for a

few seconds and said simply, "No." The newsman felt that Lucy had missed

her calling and should be rushed into the negotiations with Khrushchev

forthwith.

Relaxing (which is to say, at least sitting down for a few minutes)

with an old friend in her dressing room that spring afternoon, Lucy

alternated between abrupt sentences and spilled-over paragraphs. On the

subject of her immediate plans, she talked almost as though by rote.

"I start rehearsals this week for a picture with Bob Hope. It's

called 'The Facts of Life.' [She did not wince at the title.] I liked it

the minute I read the script and said I'd do it if Bob would. It's

written and produced by Norman Panama and Melvin Frank. We have a

10-week shooting schedule.

"Then I go to New York with the two children, my mother and two

maids. We have a seven-room apartment on 69th Street at Lexington. I'll

start rehearsals right away for a Broadway show, 'Wildcat.' It's a

comedy with music, not a musical comedy, but the music is important. I

play a girl wildcatter in the Southwestern oil fields around the turn of

the century. It was written by N. Richard Nash, who wrote 'The

Rainmaker.' He is co-producer with Michael Kidd, the director. We're

still looking for a leading man. I want an unknown. He has to be big,

husky, around 40. He has to be able to throw me around, and I'm a pretty

big girl. He has to be able to sing, at least a little. I have to sing,

too. It's pretty bad. When I practice, I hold my hands over my ears. We

open out of town - I don't know where - and come to New York in

December. [Ed. Note: "Wildcat" is now scheduled to make its debut in

Philadelphia in November.]

"I'm terrified. I've never been on the stage before, except in

'Dream Girl' years ago. But we always filmed I Love Lucy before a live

audience. I knew a long time ago that I was eventually going to go to

Broadway and that's one reason why we shot Lucy that way. But I'm still

terrified. The contract for the play runs 18 months. Maybe it will last

that long. Maybe longer. And maybe it will last three days."

The phone rang. A man's voice, the resonant kind which a telephone

seems to make louder, wanted to know if Lucy would like to go out that

night.

Lucy's expression indicated that the whole idea was a bore but the

man prattled on. He apparently had a commitment to attend a young

night-club singer's act.

"I've seen him twice already," Lucy said into the phone, "and his

press agent is now saying I've been there eight times. If I go again the

kid will be saying I'm in love with him. He's 2-feet-6 and nine years

old. I don't want any part of it." The voice on the phone turned to a

tone of urgent pleading. Lucy held the phone away from her at arms

length and looked to the ceiling for advice and guidance. She finally

hung up.

"I go out because people ask me to," she said. "I have no love for

night clubs, unless there's an act I especially want to see. And I don't

especially want to see this kid's again."

She lit another cigarette. "Nervous habit," she said. "I don't

inhale, never did. Just nerves.

"I get tired too easily. The reaction is beginning to set in. I've

had pneumonia twice in a year. That's not good."

There was a long silence. Even for old friends, Lucy is not an easy

person to talk to.

"I filed for the divorce the day after I finished my last piece of

film under the Westinghouse contract," she said suddenly. "I should have

done it long ago."

Would there ever be any more Lucy-Desi specials like those

Westinghouse had sponsored?

She stared. "No," she said abruptly. She paused. "Even if

everything were alright, we'd never work together again. We had six

years of a pretty successful series and two years of

specials. Why try to top it? That would be foolish. We always knew that

when the time came to quit, we'd quit. We were lucky. We quit while we

were still ahead."

Was she happy?

Another stare. "Am I happy? No. Not yet. I will be. I've been

humiliated. That's not easy for a woman."

She started to talk about the recent years with Desi. She talked in

a quiet, factual monotone, a voice that had been all through bitterness

and was now beyond it. She talked with an implicit faith that what she

was saying was off the record. It was.

Some day, it was suggested to her, somebody was going to write the

story. She stared. "Who would want to?"

She looked over at the framed picture of Desi that stood on a small

table. "Look at him," she said. "That's the way he looked 10 years ago.

He doesn't look like that now. He'll never look like that again."

The door was opened and a spring breeze began drawing some of the

heavy cigarette smoke out of the room. Lucy smiled a little and turned to

her desk.

"Try to write," she said finally, "more than I said but not as much

as I said."

Vintage Lucy Articles | Contents | teddyn13@oocities.com