Source:

California Pacific Medical Center

INTRODUCTION:

Challenges

facing our current treatment of HCV include lack of efficacy in genotype

I individuals (who represent a majority of U.S. HCV infections), combination

therapy’s toxicity, the expense and difficulty of therapy and the poor

reception of these treatments by many patients. The development of new

hepatitis C antiviral agents is critical to our management of this epidemic

disease. A number of approaches are under investigation including long-acting

interferons, immunomodulators, anti-fibrotics, specific HCV-derived enzyme

inhibitors, drugs that either block HCV antigen production from RNA or

prevent normal processing of HCV proteins, and other molecular approaches

to treating HCV; such as ribozymes and antisense oligonucleotides.

LONG-ACTING

INTERFERONS**:

The

poor sustained responses seen in three times a week dosing of interferon-á

(IFN) may be related to the inability of this regimen to maintain therapeutic

IFN levels and thereby exert sustained viral pressure. The creation of

pegylated interferons (PEG-IFN) has produced compounds with prolonged absorption,

decreased renal clearance and lack of antibody production. These compounds

have a longer half-life compared to regular interferons and thus may be

given once weekly with excellent therapeutic levels. A recent study demonstrated

sustained virologic response rates (SVRs) of 35% in HCV patients who were

previously untreated. The adverse events and laboratory abnormalities associated

with PEG-IFN appear to be similar to those seen with IFN therapy and significantly

less than those seen with combination therapy. PEG-IFN appears to offer

improved efficacy in cirrhotic patients as well. Two large multi-center

phase III trials recently confirmed that both peginterferons are better

than standard IFN. The improved efficacy and ease of use of these drugs

will almost guarantee their substitution for our current IFNs.

The results of a large (n=1,530), multicenter, randomized trial of PEG interferon alfa-2b (PEG Intron) plus ribavirin compared to Rebetron have now been published. This study clearly showed that there was an effective dosage of PEG Intron which is weight-based (1.5mcg/kg) that is more effective than Rebetron in genotype1 low viral load patient ( 2 million copies) or genotype 2 or 3 patients. The study used a fixed dosage of ribavirin (800 mg/) rather than weight-based dosing, so we do not know if ribavirin should be given as a weight-based regimen (as we do with standard IFN alfa-2b) or a fixed lower dosage of 800 mg/. As well, all patients were treated for 48 weeks so we do not know if genotype 2,3 patients may be successfully treated for only 24 weeks.

A second trial (n=1,121) of combination pegylated (40kD) interferon alfa-2a (PEGASYS) in combination with ribavirin given at 1,000 to 1,200 mg/ showed improved efficacy for both genotype 1 (46% vs. 37%, P=0.016) and genotypes 2,3 (76% vs. 61%, P=-0.008) over Rebetron. These results have been presented in abstract form at a major meeting but have not yet been published. No head-to-head trial of the 2 compounds has been performed so it is difficult to directly compare them to one another.

PEG Intron and ribavirin (Rebetrol) have both been FDA approved and are available for clinical use. PEGASYS is not expected to be FDA approved until the second half of 2002. The retail price of combination PEG Intron and ribavirin for 48 weeks will be approximately $25,000.00.

**

NOTE:

PegIntronA

(Schering Plough) has been approved by the FDA as of 2001 and is being

used in conjunction with Ribavirin, and Pegasys (Roche) will be approved

by the end of 2002. PegIntronA has a waiting list of close to 6 months

before being allowed to start treatment. Studies show that the Pegasys

has a better response rate than the PegIntron.

IMMUNOMODULATORS

/ ANTI-FIBROTICS / CYTOPROTECTIVE AGENTS:

A

number of immunomodulators, anti-fibrotics and cytoprotective agents which

might be helpful blocking liver cell injury caused by HCV are currently

under study. Many of these drugs have been given with interferon, growing

on earlier lessons learned from ribavirin, which was ineffective when tested

alone. A histamine analogue, which appears to improve efficacy of IFN looks

promising and a trial of the drug in combination with long-acting IFN is

currently underway in Europe.

Interferon gamma-Ib has been shown to be effective in reversing fibrosis (scar formation) of the lung in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. It is now being studied in patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis due to HCV to determine if it will reverse or halt the progression of their disease.

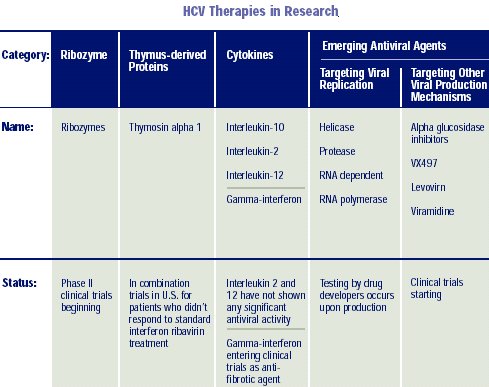

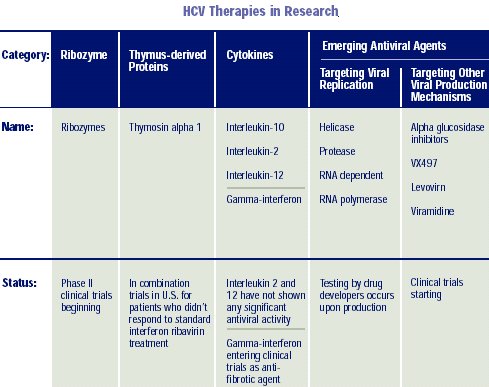

Other possibly useful drugs under study are IMPDH (inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase) inhibitors, which have anti-inflammatory and antiviral activities similar to ribavirin and thymosin-alfa1, an immunomodulator to be studied in combination with peginterferon alfa-2a. Less promising drugs in prior trials have been IL-12, IL-10, Ursodiol, glycyrrhizin, and combination IFN with amantadine or rimantadine.

HCV

ENZYME INHIBITORS / PROTEIN PROCESSING INHIBITORS:

The

ideal targets for new drug therapies are viral enzymes critical to HCV

replication. This targeting strategy has been quite successful in HIV suppression

and serves as a logical model for HCV drug development. Unfortunately,

the HIV protease enzymes are aspartase based, whereas the HCV protease

is serine based and therefore HIV protease inhibitors have no effect on

HCV replication. As with HIV, the use of viral enzyme inhibitors in HCV

therapy would likely cause drug-resistant mutations.

There are 3 likely target enzymes: the HCV protease, the HCV helicase, and HCV polymerase enzymes. Each has a crucial step in virus replication. The crystal structure of the hepatitis C N53 protease enzyme was published in 1996; however, an effective inhibitor has not been produced. NS4A and NS43, other HCV proteases, are additional targets.

The polymerase enzymes will be the first inhibitor drug target in humans. A number of groups have described the three-dimensional structure of these enzymes and have inhibitors in animal studies. The first human trials (phase 1) are currently underway.

T-CELL

IMMUNOTHERAPY:

Cytotoxic

T lymphocytes (CTL) play an important role in viral clearance and subsequent

humeral immunity in hepatitis B patients. In a similar fashion, it is thought

a CTL response contributes to HCV clearance in those few individuals that

have spontaneous resolution of infection. A vigorous, polyclonal CTL response

is seen in both chimpanzees and humans who clear infection, whereas HCV-specific

CTL’s failed to develop in those with chronic infection. A number of groups

have created vaccines utilizing CTL epitopes and plan to use them as potential

HCV therapy. None are in human trials yet.

MOLECULAR

APPROACHES TO HCV THERAPY ANTISENSE OLIGONUCLEOTIDES:

Antisense

drugs block the synthesis of disease-causing proteins by preventing translation

of mRNA. In the case of HCV, an antisense oligodeoxynucleotide directed

against a specific HCV sequence effectively inhibits viral gene expression.

This construct concentrates in the liver when given by intravenous infusion.

A number of HCV-infected patients have received this antisense oligonucleotide

infusion in a phase I/II trial at our center to demonstrate safety and

tolerability. The efficacy of the compound is currently in a phase 2 trial.

RIBOZYMES:

Stabilized

Ribozymes, small catalytic RNA molecules directed against a specific region

(5’-UTR) of the hepatitis C virus genome (that is highly conserved across

the various genotypes of HCV), are currently being tested as novel therapy

for HCV infection. The 5’UTR region of viral RNA functions as an internal

ribosomal entry site (IRES) and participates in the HCV genome translation

within the cell to produce infective virions. A ribozyme directed to this

viral RNA region might effectively block the viral translation and expression

in the host cell.

The possible synergistic effects of the combined active ribozyme preparation and type 1 interferon (IFN; Infergen®) are currently being studied in a phase 2 trial in the U.S.

SUMMARY:

Our

current state of the art chronic HCV therapy is at best, adequate for a

minority of patients (non-I genotypes), in addition to being cumbersome,

toxic and difficult to administer. For these and other reasons, physician

and patient acceptance has been limited and only a few percent of infected

individuals receive treatment.

Pegylated interferons have been introduced this year offer improved efficacy and ease of use. The combination of PEG-IFN with ribavirin will be the standard of care for treatment of HCV for the next 3-5 years.

We are at the leading edge of new therapeutic approaches to HCV including antisense therapy, hammerhead ribozymes, and specific enzyme inhibitors such as RNA polymerase. When such agents become available, we may treat HCV as an infectious disease, rather than a liver disease. Ultimately, we need oral drugs that are easy to take, non-toxic, inexpensive and efficacious across all HCV genotypes and subtypes.

SOURCE:

Paul

J. Pockros, MD

Center

for Liver Diseases

Scripps

Clinic, La Jolla, CA

Source:

California Pacific Medical Center