Stephen Stockwell is a lecturer in Journalism at Griffith University's Gold Coast Campus. He has worked as a journalist at 4ZZZ, JJJ and Four Corners and as a political media consultant. He has also written and produced BrainBlast, a video feature in the splatter genre.

Abstract:

Media treatment of the Port Arthur massacre fits comfortably into Cohen's (1973:23) general schema of moral panic but, as the perpetrator's motivation was probed in the inventory and reaction stages, some thematic elements of that panic were stretched (such as gun availability and video violence) while others were cut short (the perpetrator's personal development and racism). Delineating the context of these editorial decisions reveals a shift in the function of moral panic from the socially constructed media event chronicled by Cohen to the hegemonically deployed media instrument symptomatic of the contemporary media environment. Nevertheless the simultaneous shift in the site of moral panic deconstruction from class-based sociology to audience-based media theory suggests trajectories for the subversive use of moral panic.

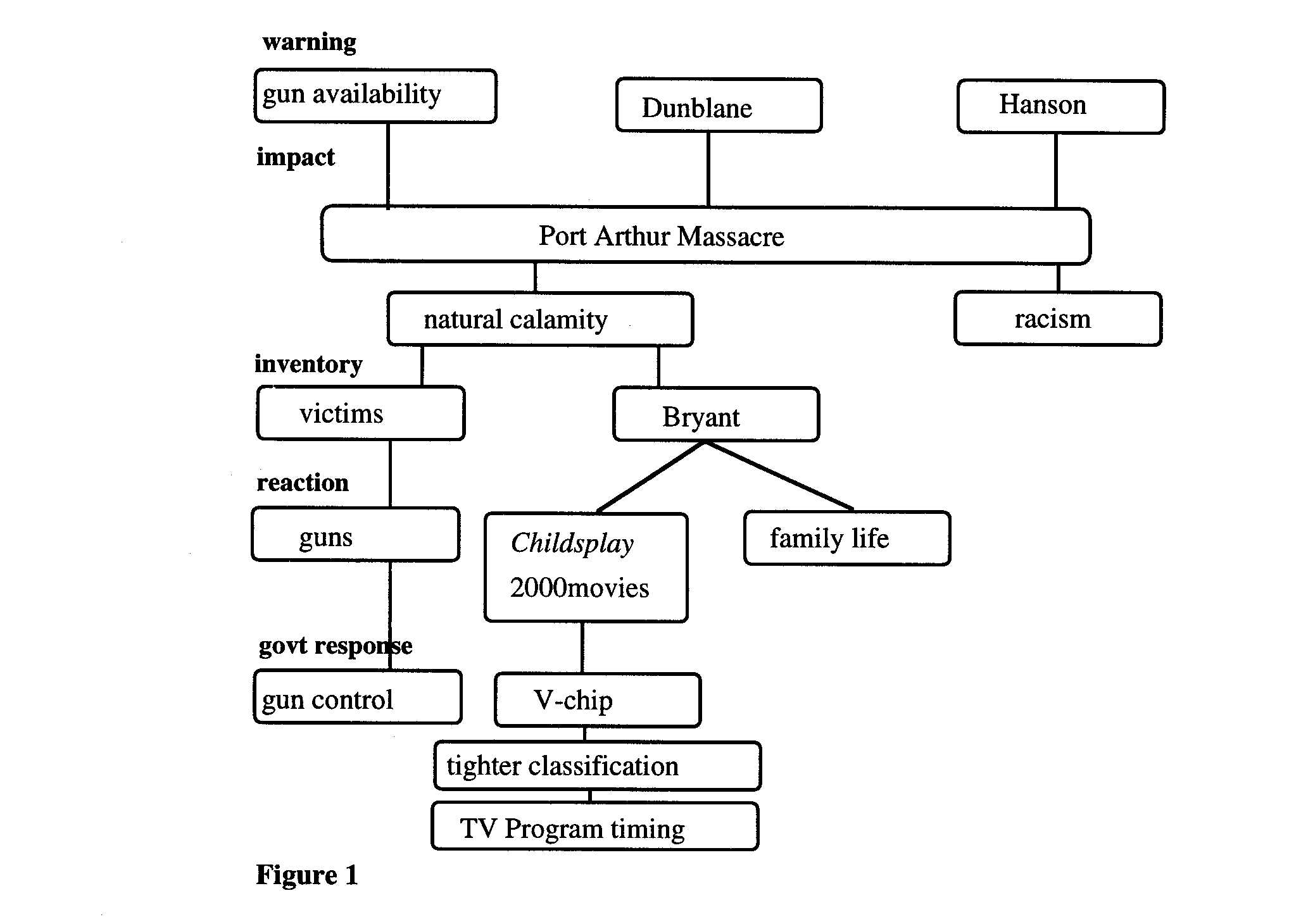

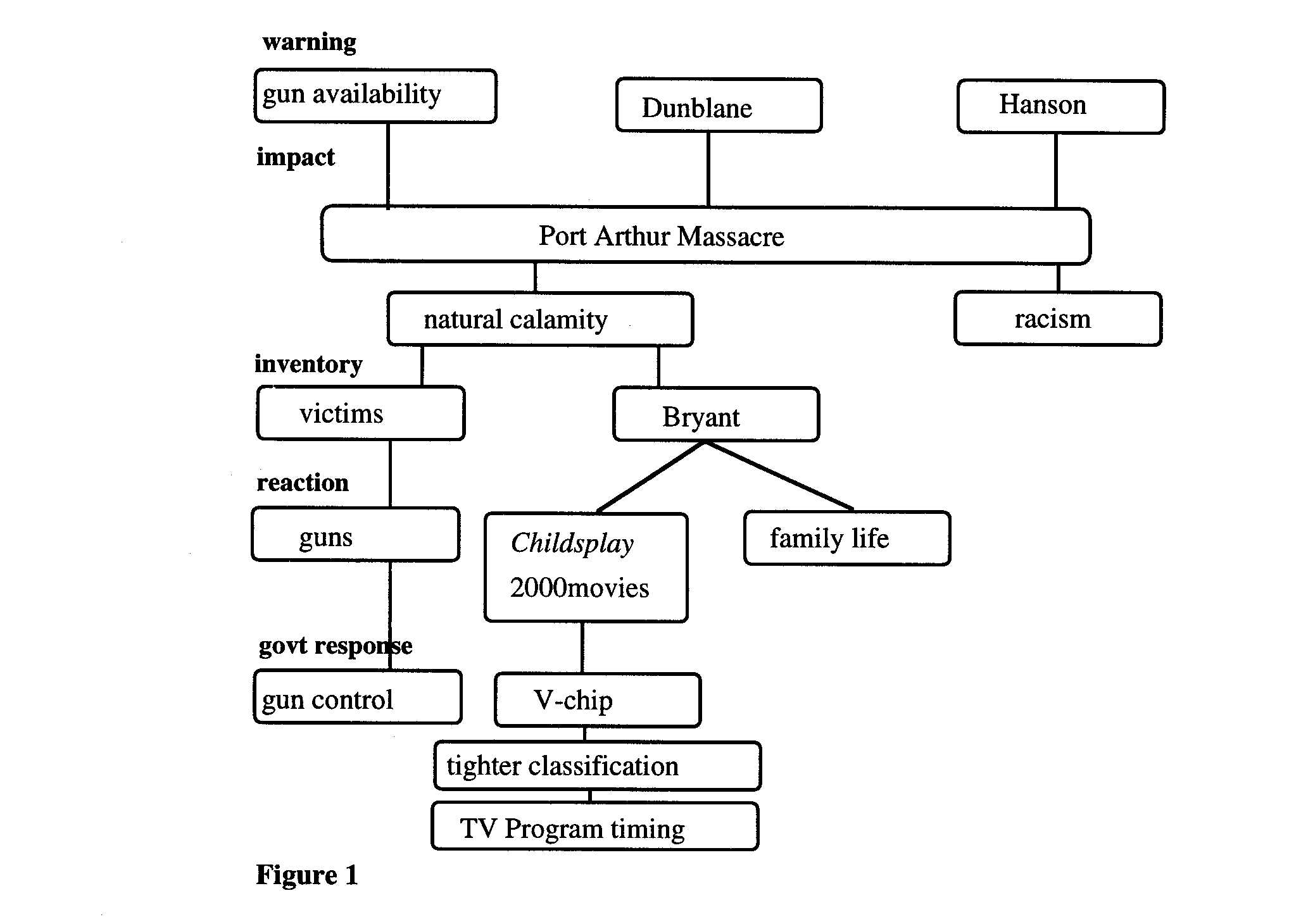

On Sunday 28 April 1996, Martin Bryant murdered 35 people at Port Arthur, Tasmania and in surrounding districts. The Port Arthur murders sit at the intersection of numerous media themes and this paper begins by disentangling those themes against Cohen's (1973:23) model of moral panic: warning, impact, inventory and reaction (see figure 1). This provides an opportunity to clarify the mechanics of moral panic thirty years after the now-seemingly innocent frolics of the Mods and Rockers, the "folk devils" whom Cohen studied.

Of particular interest is the way in which some thematic elements were

pursued and transformed into fully-fledged moral panics with resultant

changes in government policy while others petered out into what, on reflection,

might be seen as an embarrassing silence.

Looking back at the media prior to the incident, we can now discern the warning phase which, as Cohen explains, involves: "some apprehensions based on conditions out of which danger may arise" (1973:22). The intense media coverage of the Dunblane massacre in the weeks before the incident and earlier stories about the easy availability of high-powered guns in Tasmania are two obvious examples. A less obvious example, the relevance of which will be discussed below, is the media attention afforded to the racist statements of Pauline Hanson and other conservative politicians during the March 1996 Federal election campaign.

Media coverage of the incident itself fits easily into Cohen's description of impact: "during which the disaster strikes and the immediate unorganised response to the death, injury and destruction takes place" (1973:22). In situations like this, journalists are acting by instinct, struggling to comprehend and clarify events for a string of tight deadlines. For want of analysis, they find themselves drawing parallels to natural disasters or inexplicable calamities and resorting to ghoulish compilations of previous similar events and international coverage of this particular instance. While this instinctual, unorganised response has been criticised (Mediawatch ABC-TV 6 May 1996), it is very difficult to prescribe the correct manner of dealing with such a large, complex and emotive event except to proscribe clear criminal or ethical breaches, for example unauthorised entry to the perpetrator's home (Mediawatch ABC-TV 6 May 1996). It was in the confusion of the impact phase that the few brief references to a possible racist motive were made (Daybreak Nine Network 29 April 1996). The end of the impact phase was marked by the normalising pieces to camera by Current Affair's Ray Martin from Port Arthur on the evening of 29 April. Over the following two days the inventory phase unwound with front page lists of the victims, the survivors recounting their close shaves and the exploration of the minutiae of Bryant's circumstances.

Real Devils

As the media environment settled after the murders, the shift from inventory to reaction was skilfully managed by the newly elected Howard Liberal Federal Government which used the opportunity to pursue two particular policy initiatives.

The first was to limit the availability of some semi-automatic weapons. It is interesting to consider whether this initiative was the result of a moral panic about guns or whether the murders merely prompted the government to take action which had widespread popular support before the Port Arthur incident. Certainly the Prime Minister announced his position after A Current Affair replayed a story which had previously displayed the ease of acquiring such weapons in Tasmania (Nine Network 29 April 1996) but he acted so quickly that there was no opportunity for a fully-fledged panic to develop.

In this context an interesting issue arises for Cohen's account of moral panic generally. Given that the clear link between the availability of firearms and high rates of murder, suicide and fatal accidents in domestic situations had already been established (Gabor 1994), it is relevant to ask: is it possible to have a moral panic when the devils (guns) are real?

Opponents of gun control certainly attempted to generate a moral panic about the government's plans to limit gun availability. At a meeting in Gympie, vice-president of the Firearms Association, Ian McNiven, labelled the Prime Minister "Jackboot Johnny" and described his position as a "brutal, totalitarian" attack on the freedom of citizens. McNiven went on: "Let me tell you something about freedom. You can only buy it back with the most expensive currency in the world. Once given up, freedom can only be bought back with blood." (Agence France Presse May 16 1996)

In contrast to the close focus on the issue of gun control in the reaction phase, Bryant's history of social development received only passing mention in the press despite the weight of criminological literature which suggests that it is interpersonal trauma during childhood development which predisposes a person to violence and murder (Klapper 1960; Yarvis 1991; also "Predators" Four Corners 14 April 1997). See also Eisenberg (1980) on the role of adult sanction in predisposing children to violent responses.

Given that the conservative Federal and State Governments were involved in cutbacks to health and social services, a moral panic about the declining quality and availability of psychological services would appear justified. But instead the media ignored this path as too difficult and instead concentrated on Bryant's video viewing habits.

2000 Violent Videos

The second major government initiative prompted by the Port Arthur murders was another in the long series of inquiries into violence in the media (Stockbridge 1997). This initiative encouraged a moral panic about violent TV and videos to develop. The genesis of this moral panic is of particular interest. It began with Jana Wendt asking the ubiquitous American expert about the contribution of the perpetrator's family background to the murders (Witness Seven Network 30 April 1996). In a neat piece of spin control, the American responded by avoiding the question and raising the issue of violent videos.

The Australian media were quick to pick up the theme. A few quotes from the print media eloquently sketch the course of the moral panic about video violence from that point on:

"Bryant was also known for his love of movies, a passion he indulged with visits to Hobart video outlet Movie Madness..." (Daily Telegraph May 1 1996)

"Bryant's favourite video Child's Play 2 - featured an evil doll called Chucky. 'He loved Chucky,' Jenetta (his former girlfriend) said. 'He used to go on about it all the time... There was a phrase out of that movie he used to say: "Don't fuck with the Chuck." He used to get excited when he said that.'" (Daily Telegraph May 3 1996)

"Bryant's days consisted mainly of watching movies. His deserted house this week was littered by more than 20 videos. They were mostly violent American films, which local video stores said were his favourites." (Courier-Mail May 4 1996)

"More than 2,000 violent and pornographic videos have been found at the home of Martin Bryant, the man accused of the Port Arthur massacre. The tapes, lining shelves in two rooms, were discovered when work began to empty his house in the Hobart suburb of New Town." (Daily Telegraph May 15 1996)

This final claim was later refuted by the head of the Film Classification Board, John Dickie whose investigations revealed that the 2,000 videos were predominantly "musicals and classics... that belonged to the woman who owned the house previously (and) the only four videos that were not in that period of romance and dramas were two of Rowan Atkinson's Blackadder, one of Nightmare on Elm Street and one of Taxi Driver." (Sydney Morning Herald June 29 1996:2) But by then the panic had spread like a virus from hard news into the editorials and features (for example "The message of violent media" Australian May 11 1996:23) and was making opportunistic adaptations within other stories (for example "Designer Deaths" Courier- Mail June 3 1996 criticises "ghoulish" photography in fashion magazines).

Child's Play

"Blaming" movies, and in particular the Child's Play series (Child's Play 1988, Child's Play 2 1990, Child's Play 3 1992), fitted easily into the media's scheme of things. The unfinished nature of the media effects debate, the popular view that violent movies can't be good for other people (while having no effect on me) and the right-wing tenor of the censorship case (which balanced the "left-wing" gun control lobby) all combined to make violent videos a far easier issue to "debate" than more difficult questions such as personal development and the shrinking social safety net.

Further, the Child's Play series already had a criminal record. Child's Play 3 had been implicated in two murder cases in Great Britain. Eleven year old boys, Jon Venables and Robert Thompson had murdered toddler Jamie Bulger in February 1993 shortly after one of their fathers had rented Child's Play 3. While the father claimed the boys never had the opportunity to view the tape, there were some similarities between the murder of the child and activities in the movie and while the police did not seek to make a connection between the movies and the murder, in sentencing the boys, the judge attacked the availability of violent videos (Press Association Newsfile May 4 1996).

There was also: "the torture and murder of 16-year old Suzanne Capper by five women in December 1992... (one of whom) Bernadette McNeilly, 27, had allegedly watched Child's Play 3 and said "I'm Chucky. Wanna play?" before injecting her victim with amphetamines" (Sun-Herald May 5 1996). Also "Police believe a cassette of the doll's chilling and robotic "I'm Chucky. Wanna play?" catchphrase was repeatedly played to (Capper) through headphones while she was tied to a bed for days on end" (Sunday Age December 19 1993).

Analysis of the thematic content of the Child's Play series goes some way to suggest why this series was such an easy target for demonisation. The three movies feature Chucky, an orange-haired "Good Guy" doll possessed by the soul of a dying mass murderer using voodoo and black magic. The doll then murders people in increasingly inventive ways as it attempts to shift its soul back into a human form.

A slasher movie centred on a doll who practises black magic is an open invitation to censorship advocates. As one critic said: "This is certainly not Pinocchio or Babes in Toyland" (Harrington Washington Post November 10 1988). While the Child's Play series never strays far from the conventions of the slasher movie (for more on those conventions see McCarty 1984; Scott & Stockwell 1987) and may be read as a camp homage to the genre (Parker 1988), the counter-intuitive malevolence of a doll terrorising a child produces a problematic space - Alice in the Twilight Zone - and its own bent dynamic.

Corporate Interests

Aside from its thematic content, there were other issues in its production history and corporate position that made Child's Play 2 an acceptable target for a moral panic. The series was the product of young writers and directors with little studio support. The first instalments in the series were made relatively cheaply and produced strong box office returns. The third was a more extravagant production that barely covered its cost. There were no big stars, each movie had a different distributor and the critics agreed that Chucky had mined about as much as he could from the horror genre. There was little chance of Child's Play 4 going into production and the series did not have the studio support or media connections to defend itself.

By picking out Child's Play 2 , the news media avoided any stigma for their own coverage of the mass murder at Dunblane which friends of Bryant suggested may have been a trigger and also undercut criticism of violent product from the mainstream studios with which the Australian news media share close ownership and distribution links.

The result of the moral panic over video violence has been government action to produce more stringent classification of movies, further limiting timeslots in which adult material might be broadcast on television and requiring all new TVs to contain a V-chip that allow parents to limit their children's viewing (Stockbridge 1997). Meanwhile the Child's Play series is still on the video shop shelves and one is left with the concern that the combined effect of the V-chip and the review of classification ratings is that the baby could go out with the bath water: these changes can just as easily be used to censor Shakespeare or graphic war footage as Chucky's bizarre activities.

Racism

By concentrating on the availability of guns and media violence the media, and the government, avoided probing a key motive apparent in Bryant's statements and behaviour: racism. This is not to suggest that racism was the only motive Bryant had for the massacre. He killed 33 Australians and only two Asian tourists and he appears to have harboured an assortment of grudges and obsessions against all manner of people and institutions but it is significant that his last recorded words before the massacre began were "There a lot of WASPs around today, there aren't many Japs, are there?... I live here, and I can never get a park, with all the Jap buses" (Herald Sun April 29; The Age April 30). Just as revealing as Bryant's comments before the massacre are his actions in the Broad Arrow restaurant where the murders at Port Arthur began. From a close re-reading of the most thorough summaries of his actions ("The Carnage Cafe" Sydney Morning Herald May 4 1996; "Slaughter of Innocence" Sun Herald 5 May 1996) it is apparent that from the moment Bryant took out his gun, he was moving towards the only Asian tourists in the restaurant. They were his third and fourth victims there. None of the summaries made this point explicitly and some even failed to include mention of the Asians among his victims (see for example "In Cold Blood" The Age May 3 1996). Also, while his comments prior to the massacre were reported during the confusion of the impact phase and some media outlets even pointed to their racist implications, that particular story ended there and did not even feature significantly in the inventory phase.

That the media failed to pursue racism as a motive and their subsequent concentration on guns and violent videos as prime causes of the murders raises some interesting questions. Why was a moral panic on racism deemed un-newsworthy? Do media managers see racism as so popular that it would not successfully demonise Bryant? Might the charge of racism increase sympathy for him? Did they judge that the issue might raise too many questions about Australia's attitude to race at a time when it was under international scrutiny? Or do they share, perhaps unconsciously, a certain complicity with the high level of racism in Australia, a complicity that was veiled by their readiness to instigate moral panics about other, carefully delineated, issues but not this one? It is beyond the scope of this paper to answer these questions in a thorough-going fashion though it is instructive to consider the AGB-McNair opinion poll taken in June 1996 (Sydney Morning Herald June 19 1996:6) which showed that 51% of those interviewed think that Australia's composition of migrant intake features "too many from particular regions" which suggests that over half of Australians are willing to discriminate against migrants on the grounds of geographical, and therefore, racial origin.

Some Implications for Moral Panic Theory

The media coverage of the Port Arthur massacre raises some interesting insights into moral panics in the contemporary media environment. One point worthy of note is how the role of "the moral entrepreneur" (Cohen 1973:111-132) has shifted. No longer does a moral panic require "massed Basil Fawltys" to identify the folk devils and initiate an "Informal Social Control Culture" (Jones 1997). While the media rounded up the usual suspects (like Senator Brian Harridine) to play the role of moral entrepreneur in initial news coverage about video violence, it is apparent from the orchestrated nature of the video violence panic that its real entrepreneurs were the government and the media themselves. Close analysis of the interchanges that accelerated the video violence issue out the spiral of silence shows the work that went into fuelling the panic. From the spin applied by the American expert discussed above there was subsequent close media attention to Bryant's viewing habits that led to the Prime Minister's statement announcing the inquiry. That statement was reported in similarly packaged news stories on various TV networks before being formalised by editorials and features and expanded into barely related issues (fashion photography) and outright fantasy (the 2000 violent videos).

Another point to note is that moral panics no longer need the focus of "deviant" lower class males as folk devils: Mods and Rockers in Cohen (1973), muggers in Hall (1978), larrikins in Morgan (1997). Guns and videos, though perhaps most feared in the hands of "deviant" lower class males, are nevertheless objects, not people. This reflects the shift of moral panic theory out of sociology and into media theory. While Cohen set precedent for this shift in his original work when he pointed to the media's "ideological exploitation of deviance" (Cohen 1973:166) in the production of moral panic around the Mods and Rockers imbroglio, that analysis is clearly rooted in the sociology of deviance rather than in any sociology of the media. Later Cohen himself acknowledges the influence of Stuart Hall and others who delineated "the active social processes by which news is selected and created" (Cohen 1981:10), processes by which the media, as Hall et al (1981:365) say: "albeit unwittingly and through their own autonomous routes - have become effectively an apparatus of the control process itself."

This leads to the third point of note: the selectivity of the media in promoting some moral panics while others are allowed to fall by the wayside. It is important to question why government sanctioned moral panics about gun availability and media violence received so much media coverage (while carefully deflecting blame away from the media corporations themselves), while equally germane issues such as the perpetrator's personal development and racism were ignored. The inability of the media to inquire about their own motives was brought home to me while doing the media rounds prior to the Moral Panic conference earlier this year. While journalists had no problem with exploring the issue of moral panics and, in fact, could not hide their glee at the prospect of generating a moral panic about moral panic, there was a hesitancy in accepting that moral panics always serve some interest. This came to a head on Phillip Adams' Late Night Live (ABC Radio 3 April 1997) when it was suggested that among those interests served by moral panic might be the interests of media corporations themselves. Adams, an employee of Rupert Murdoch's News Corporation, was quick to dismiss such "conspiracy theories". But in light of the concentration of media ownership, the convergence of media capital and its integration with other forms of capital, it would be hardly surprising if the main interest served in the production of moral panics was the media's own corporate interest. In this environment, journalists may be their own worst enemies as they remain happily ensconced in a web of reflexive criticality and uncritical reflexivity - ready to promote a moral panic about moral panics but unwilling to probe why it might be necessary.

Using Moral Panic

These three points are a natural progression from the moral panic/media manipulation scenarios of Cohen, Hall et al but to avoid the paranoiac dead end inherent in this position and alluded to by Phillip Adams, it is useful to approach moral panic from the audience's perspective. As an audience, we apprehend the moral panic discontinuously, as a cluster of disconnected elements strung out along the spectrum of news and current affairs reporting from the sober activism of investigative journalism to the gutter press hacketry of the blatantly misleading beat-up. We use the stories to stoke our moral indignation or, perversely, to side with the devil or we may just apprehend them as just a disparate collection of information passing us by. As the audience experiences it, the moral panic is just another meta-tool for organising the news, a meta-tool like beats or rounds or thematic campaigns that are used by editorial staff and public relations workers to create form from information.

Once this function of the moral panic becomes clear then two corollaries are apparent. The first is the potential, indeed the responsibility, for working journalists to take on their traditional foes in editorial and PR in order to make each moral panic transparent, even as they are engaged in producing it. Journalists can and should clarify in whose interests the moral panic works as they create it. Their challenge is finding the space to confront the very power that empowers them, particularly when their material is being vetted by the same people (editors, corporate managers) who are fomenting the panic. But working journalists have long since learnt to subvert the system, to use the text they create to imply the full story, to position themselves as the dissenting voice or, when all else fails, to leak the story to a competitor.

The second corollary of moral panic as an editorial/PR tool is the possibility that forces marginalised by the media can employ the very same tool to pursue moral panics about the devils they judge to be real. The shift in the site of moral panic from sociology of deviance to media theory reflects "the shift of emphasis from the real to communication (which) brings with it a shift from a technology of control to a technology of interactive semiotic participation where citizens of the media use TV news as their forum..." (Hartley 1996:43) As was pointed out above, there seems to be plenty of scope for moral panics about racism and the declining social safety net and they are topics that lend themselves to indignation by appropriate citizen-entrepreneurs.

Bibliography

Cohen, Stanley, 1973, Folk Devils and Moral Panics, Paladin, St Albans.

____ and Young, Jock, (eds) 1981, The Manufacture of News, Constable, London.

Edgar, Patricia, 1977, Children and Screen Violence, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, Qld.

Eisenberg, Gilbert, 1980, 'Children and aggression after observed film aggression with sanctioning adults', in Forensic Psychology and Psychiatry, eds Wright, F. et al, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, New York, pp304-314.

Ettema, J.S. and Whitney, D.C., 1994, Audiencemaking, Sage, Thousand Oaks.

Fowles, Jib, 1992, Why Viewers Watch, Sage. Thousand Oaks,

Gabor, Thomas, 1994, Impact of Availability of Firearms on Violent Crime, Suicide and Accidental Death, Dept of Justice, Ottawa.

Hall, Stuart et al, 1978, Policing the Crisis , Macmillan, London.

____ et al, 1981, 'The social production of news: mugging in the media' in eds Cohen, Stanley & Young, Jock The Manufacture of News, Constable, London.

Hartley, John, 1996, Popular Reality, Arnold, London.

Jones, Paul, 'The role of "moral panic" in the work of Stuart Hall', Media International Australia no. 86.

Klapper, J.T., 1960, The Effects of Mass Communication, Free Press, New York.

McCarty, John, 1984, Splatter Movies, Columbus Books, Bromley.

Morgan, George, 1997, "The Bulletin, street crime and the larrikin moral panic in the late 19th century", Media International Australia, no. 86.

Parker, Rand, 1988, "Child's Play: a film review" at www.shoestring.org

Scott, Paul and Stockwell, Stephen, 1987, 'If it doesn't splatter, it doesn't matter', Cane Toad Times January p31-32

Stockbridge, Sally & Dwyer, Tim, 1997, 'Recurring moral panics and new methods of regulation', Media International Australia, no. 86.

Yarvis, Richard M., 1991, Homicide: Causative Factors and Roots, Lexington Books, Lexington.