THE

ADOPTION OF BYZANTINE EQUIPMENT AND CUSTOMS BY THE VARANGIAN GUARDS

by Steven Lowe

This article appeared originally in Varangian Voice 37, of November 1995,

and has been republished here with minor amendments. It owes its origin to a

discussion with Tim Dawson quite some time ago about the composition of the

original Varangian Guard, and the extent to which its members would have

adopted Byzantine arms and armour.

It has always been assumed in the

New Varangian Guard that the Varangians in the Empire would have adopted some

aspects of the Byzantine and other cultures they met there. The Vikings are

well known to have taken on the customs and apparel of the societies they

mingled with, whether Frankish (the Normans), Slavic (the Rus), or others.

Contact with the splendors and sophistication of Byzantine culture would have

been impressive and rather overwhelming.

But to what extent would the Varangians have taken on the Byzantine

lifestyle and accessories, and how would this influence have shown itself? The

Varangian Guard was a close-knit group with high esprit de corps,

and both sagas and Byzantine sources suggest that as a relatively small group

of ex-patriates they maintained their language, dress and customs to a pretty large

degree. The most obvious areas of difference would have been in those material

things which they either did not have on arrival, or replaced during their stay.

ARMS AND ARMOUR

Both the Viking and Anglo-Saxon armies had of a core of highly experienced

and well-equipped “professional” warriors, plus a larger group of

semi-professionals drawn from the landed class and petty nobility. There is now

debate over whether their armies also included the “rabble”; peasant levies

with no experience and little equipment. However, a sizable proportion of the

figures in contemporary illustrations of warfare, from England at the least,

are without armour or helmets, carrying only spear and shield.

In the English fyrd system of the 11th century,

using Berkshire as a typical example, a shire owed one warrior to the fyrd for

each 5 hides, a hide being the amount of land required to support a family, or

about 120 acres. There were approximately 70,000 hides in England, which would

have produced 14,000 warriors. (McLynn, p.148). McLynn believes that an

exhaustive conscription could have produced up to 60,000 (ibid. p.148).

On the other hand, Edge & Paddock, (pp 15-16) estimate that England’s

total defense force consisted of the following: 3000 in the king’s own huscarls

plus another 300 or so for each of the four great earls, 15-20,000 in the

“select” fyrd, and the balance from the Great Fyrd, who were peasant levies. If

this is true, the great majority of the army would have belonged to the last

category, who were ill-armed at best.

Level of Armament among the

Varangians’ “Personnel Pools”

Even in England, which was a wealthy country, a thegn may not have had a

mailshirt, or even a helmet.

In 1008, King Ethelred II ordered the production of ships and armour; “

. . . one warship from three hundred and 10 hides, and from 8 hides a helmet

and mailcoat” (Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Peterborough Manuscript).

But this may have been intended only for the navy at a time of great military

need - it would provide 38 mailshirts and helmets per ship, which would

probably equip a major proportion of the crew. Additionally, it appears that

this was intended to be a one-off activity, and it is doubtful whether

production was continued after the original order was carried out, let alone

through the succeeding reigns, down to 1066.

On the death of a landowner, his successor paid a heriot to

the king to maintain the right to the lands – a sort of death duty. In 1020-23

Knut, the Danish king of England, laid down the heriot of each earl as 4

helmets, 4 coats of mail, 8 horses (of which 4 were to be provided with

saddles), 4 swords, 8 spears, 8 shields and 200 mancuses of gold. For a thegn

who was close to the king it was 2 horses (one with a saddle), one sword, 2

spears, 2 shields and 50 mancuses of gold. A lesser thegn was required to

provide a horse and its trappings and his weapons. (Edge and Paddock p. 29)

The heriot appears to have been a means by which the king supplied his

troops, presumably his personal huscarls, with the wherewithal for war. But as

a great earl didn’t die every day, there would still not be a great amount of

arms and armour available to the king. And what does this say about those lower

in the social structure? Even the heriot of a King’s thegn does not include a helmet

or mail shirt – is this because they did not have them themselves? If the

requirement for an earl was only four helmets and mailshirts each, what does

this tell us about the equipment of the average warrior? The battle scenes in

the Bayeux Tapestry show a large proportion of well-armoured warriors, but most

contemporary illustrations are more like the one below, showing an army in

which only the king wears a mail-shirt, and nobody has a helmet.

Anglo-Saxon, from the first half of

the 11th century (British Library, MS Cotton Claudius B. iv, fol 25r)

Anglo-Saxon, from the first half of

the 11th century (British Library, MS Cotton Claudius B. iv, fol 25r)

If the 6000 Vikings who appear to have founded the Varangian bodyguard of

Emperor Basil II circa 988 AD (Blöndal & Benedikz p.43) were of similar

proportions to the English army, most of them would have been pretty badly

equipped when they got to Miklagard. Even if a higher proportion than usual

were “professional” warriors and owned a helmet and armour on arrival, they

would still have been a relatively small fraction of the overall number. The

same would have been true for those in later contingents. By 1086, over 4000

English thegns had been dispossessed, according to the Domesday Book (Morgan p.

105). Graeme Walker proposes in Varangian Voice 35 (The English Varangians)

that post-Conquest Anglo-Saxons of the thegnly class formed a large proportion

of the later Varangian Guard. (For further information on this issue, see my

article Byzantium: The English Connection. However, as mentioned

above, they may still have been relatively poorly equipped. Arms and armour

were very expensive, a sword costing as much as 120 oxen or 15 slaves (Edge

& Paddock p. 26), and a thegn might own no more than 5 hides of land.

(Morgan p. 98-100).

Varangian Equipment

As the Emperor’s bodyguard, the Varangian Guards would be expected to have

helmet, armour, shield and a good weapon as a bare minimum, and those without

them would have been supplied from the Imperial Armoury. And those who had

their own gear would have gradually replaced it as equipment broke or wore out.

Most would probably have been supplied with basic Byzantine issue. Only

their leaders would have been given expensive, decorated equipment. Favorite

weapons would have been kept – particularly their two-handed axes; the

Varangian Guards were known in Byzantium as the pelekephoroi, or

Axe-bearers – and only replaced if they were damaged or lost.

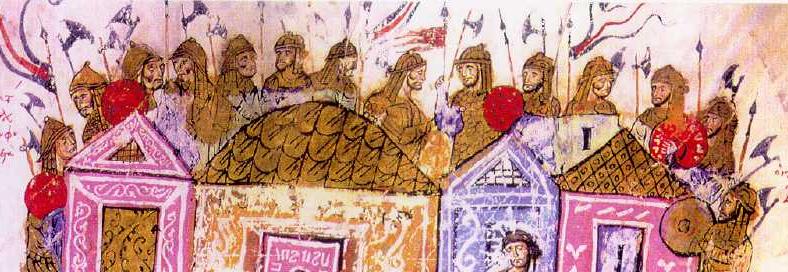

Soldiers in various types of Byzantine armour - from left; lamellar, padded kabadion, scale and mail; from a portrayal of the Betrayal of Jesus in a church in Cyprus

Soldiers in various types of Byzantine armour - from left; lamellar, padded kabadion, scale and mail; from a portrayal of the Betrayal of Jesus in a church in Cyprus

In the only contemporary illustrations of the Varangian Guard, from a copy

of the Skylitzes Chronicle held in Madrid, they are shown with typical

Byzantine helmets and shields, but they have two-handed axes and what appear to

be mail corselets, not lamellar. On the other hand, the artist in question

routinely puts Byzantine soldiers in the same armour, so there is very little

to be concluded from this.

An

illustration taken to be of Varangian Guards from the Madrid Skylitzes

Chronicle (fol. 26v-a)

An

illustration taken to be of Varangian Guards from the Madrid Skylitzes

Chronicle (fol. 26v-a)

The Sagas

There is corroborative information from the sagas, but it must be treated

with caution; not only were they written down as much as 250 years after the

events they describe, but many of them are heavily embroidered, or perhaps

wholly invented. However, they can sometimes provide useful information.

(Another issue is translation; I am using the version in Blöndal and Benedikz,

and hoping the word “sax”, for example, in the extracts below is not just a

blanket term for all types of dagger. Some confirmation is given by the fact

that when Bolli Bollasson carries what is presumably a “foreign” dagger it is

described as “a short sword as is common abroad”.)

In The Varangians of Byzantium, we encounter mention in the Heidarviga saga

of Thorstein Viga-Styrrson among the Varangian Guard in Constantinople

concealing a sax under his cloak to take revenge on Gestr Thorhallason (Blöndal

& Benedikz p.200) and in the Grettirs saga of the Varangians about to

embark on an expedition having an arms parade;

“at which every member of the unit is to produce his weapons.

Thorbjorn produces the sax which he took from the dead Grettir, and explains

the dent in the edge, how it was caused when he struck the dead man on the head

with it.” (Blöndal & Benedikz p.203).

Shields also do not last long in

combat, and anyone who saw action would soon replace his own with a

Byzantine one.

According to the Laxdaela saga, when Bolli Bollasson returned to Iceland

from his service in the Guard in about 1030-1040,

At his side he bore his sword Fotbitr [lit. “footbiter”] ; its hilt was

inlaid with gold, and so was the blade; he wore a golden helmet and had a red

shield at his side on which was drawn a knight in gold (which he had brought

from Byzantium); he carried a short sword in his hand, as is common abroad . .

.” (Blöndal & Benedikz p.207).

here

or

CLOTHING

The Laxdaela saga also says that on his return Bolli

“brought with him much money, and many precious things the great lords

had given him; he was so nice (i.e. fastidious) in his dress when he came back

from his journey that he would wear no clothes except those made of with fine

stuff (skarlat) or velvet (pell*), and his weapons were all inlaid with gold .

. . all his attendants wore clothes of fine stuff . . . he wore clothes of velvet which the Emperor had given him,

and over them a cloak of fine red cloth;” (Blöndal &

Benedikz p.206-7).

here

It would be a matter of some prestige to adopt the trappings of such an obviously wealthy and successful

society, and something to flaunt when one went home. [By the way, a

mis-translation of this passage to mean that the colour of their

clothes was scarlet is probably the original of the traditional N.V.G. Red

Tunic].

It must be kept in mind that Bolli is described as having been “many years

in Byzantium” (Blöndal & Benedikz p.206), and it is likely he would have been heavily

influenced by Byzantine lifestyle. Also, though Blöndal and Benedikz believe

the account of his magnificence to be exaggerated, it is fairly clear that

Bolli had risen fairly high in the Guard (Heath claims he had reached the rank

of Manglabites, on the evidence of his “gold-hilted” sword (p.38).

On the other hand it is less certain that all, or even most Varangians

adopted Byzantine costume. Many of them may have maintained their Scandinavian,

English or Russian dress – cosmopolitan Byzantium was accustomed to a great

variety of races and clothing styles. However, as the Empire was often hotter

than their homeland, the average Varangian might have replaced his woollen

garment with others made of lighter Byzantine fabrics – linen, perhaps cotton,

and the cheaper grades of silk (the Varangian Guard were very well paid). If he

did, his new clothes would probably have been made by a Byzantine tailor, and

this influence should also be taken into account. When his boots or shoes wore

out, they would have been replaced locally. Tailoring and boot making were

becoming specialized trades in the

Guard’s period, and there is no reason to suppose they would have made their

own clothes or footwear when high quality items were available in the markets.

Whether they would have regarded Byzantine fashions as something to be

emulated, or dismissed them as effete and decadent, is uncertain. Although

Vikings enjoyed displaying their wealth, what appeared luxurious to a Viking

barbarian would probably have been sneered at by the Byzantine nobility. In

addition, Byzantium had quite strict sumptuary laws, as mentioned in John

Sultana’s letter in Varangian Voice No. 34 of February 1995. The> Skylitzes

Chronicle (fol. 208) shows them in what could be described as “generic”

mediaeval outfits, certainly without the gold decorations so fashionable among

Byzantines, at least of the upper classes.

“The men are either all

barelegged or wearing purple-brown hose, as there is no sign of footwear.”

click here to see the full article

FOOD & TABLEWARE

Crockery wears out or breaks, and is difficult or impossible to repair, so

it is likely that it would gradually be replaced with what was available in the

City; this would have included not only Byzantine, but also Arab, Persian and

Turkish wares. A Varangian would probably have held on to a particularly good

table knife or spoon, but quality cutlery would have been widely available in

the markets, and he could well have added these to his equipment.

here

Finally, cooking gear would almost certainly be Byzantine. A point made by

Tim Dawson is that the Varangian Guard would not have cooked for themselves, as

combat units in the Byzantine army were assigned local servants – the Byzantine

equivalent of the transport and catering corps – to do such menial tasks. And

the Varangians would probably have eaten Byzantine food. Even though they would

not have been served gourmet fare as described in Varangian Voice No. 36

(Jeanselme & Oeconomos), the reaction of a Viking accustomed to boiled pork

and cabbage, to meals liberally smothered in garum, doesn’t bear

thinking about!

RELIGION

The assimilation of Byzantine ideas about the world, particularly religion,

is problematic. The Anglo-Saxons and the later Vikings were Christians, and

though they were Western (Catholic) rite, it is possible that they were

influenced by Byzantine ideas on religion. However, given that Orthodox

services were conducted in a language foreign to most Varangians, and that the

average Western mediaeval man’s Christianity was at best rudimentary and

interlarded with superstition, it would be difficult to gauge what influence,

if any, Greek thought had on the Vikings who served there.

PUTTING IT INTO PRACTICE

So what does this mean to us as re-enactors? Firstly, if we want to

accurately represent the Varangian Guard as they were, we should keep in mind

that many of the rank and file would probably have worn Byzantine

equipment. (The fact that we don’t

accurately know what equipment the Byzantines wore is another

matter again). Secondly their dress, tableware and other accessories would have

become increasingly influenced by Byzantine and other cultures the longer they

stayed in the Empire.

With the wider scope adopted by the N.V.G. nowadays, this obviously does not

apply to those of us who wish to represent other societies and cultures than

the Varangian Guard. However, as long as it is made clear that it is, say, Irish Vikings who are being

portrayed, there should be no cause for confusion.

REFERENCES:

- Beatson, P. Another

Illustration of Varangian from the Skylitzes Manuscript, Madrid Varangian

Voice No. 23, July 1992

- Blöndal, S & Benedikz,

B. The Varangians of Byzantium, Cambridge University Press,

1978

- Edge, D. & Paddock,

J.M. Arms and Armour of the Mediaeval Knight, Bison, London

1988

- Heath, I. Byzantine

Armies, 886-1118 Osprey, London 1979

- Jeanselme, E. &

Oeconomos, Food and Culinary Recipes of the Byzantines.

Proceedings of the Third International Congress of the History of Medicine

(1922) pp. 155-168

- McLynn, F. 1066 The

Year of Three Battles.

Jonathan Cape, London 1998.

- Morgan, K.O. The

Oxford Illustrated History of Britain, Oxford University press 1984

- Sultana, J. On the

Wearing of Purple. Varangian Voice No. 34, February 1995

- Swanton, M. (trans.) The

Anglo-Saxon Chronicles. Phoenix Press, London 1996

- Walker, G. The

English Varangians, Varangian Voice No. 35, May 1995