Hot Summer in the Pacific

Hot Summer in the Pacific

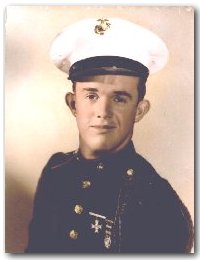

Pfc. J.W. Foster, Company M, 3rd Battn, 2nd Division

U.S. Marine Corp Pfc. John W. "Jake" Foster stood with his hand on a palm tree just as an enemy sniper's bullet whizzed by striking the tree between.his fingers. Although the 20-year-old Foster did not get hurt, the experience set off a new reality in his mind about where he was and what he was doing.

U.S. Marine Corp Pfc. John W. "Jake" Foster stood with his hand on a palm tree just as an enemy sniper's bullet whizzed by striking the tree between.his fingers. Although the 20-year-old Foster did not get hurt, the experience set off a new reality in his mind about where he was and what he was doing.

"I realized this was the real thing," Foster, now 76, said as he reflected back on his first taste of combat on Guadalcanal Island during World War II. Summers are usually a time for Foster to ponder back on those same seasons of 1942 and 1944 which could have been the last summers of his life.

Being born and raised in Blevins, Ark., Foster graduated Blevins High School in 1940. He met his future wife, Janette Rankin of Murfreesboro, Ark., the same year he graduated. The couple had just gotten home from the movies one December Sunday in 1941 when they heard the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor. "We knew we were about to get in it anyway," said Foster, who was working in a shoe store in Hope, Ark., at the time. Foster went to Little Rock and joined the U.S. Marines Corps on May 13, 1942. "Back then, everyone was going overseas to fight Germany, but I didn't want to be in nay cold weather so I joined the Marines (who were being sent mainly to the Pacific at that time)."

After 13 weeks of basic training, Foster was assigned to the U.S. 2nd Marine Division as a 30 caliber infantry machine gunner and shipped out from California to New Zealand for further training. Foster soon got reassigned to combat on Guadalcanal at the southernmost tip of the Solomon Island chain in the South Pacific.

"That's when I found out what war was really like," he said. "The first day on Guadalcanal, I was standing with my hand up on a palm tree when a bullet hit the tree right between my fingers. Helping hold the Marines' Henderson Air Field on the island became his first combat assignment. "We would take the field during the day and then the enemy would take it back during the night," he said. Fighting on that humid, tropical island, thick with jungle foliage, nearly became a six month war of attrition for both the Americans and Japanese.

"We only had what we could carry on our backs. We didn't have a change of clothes," Foster said. "We couldn't shave and our toenails became infected with fungus and rotted off." Death and sickness only deepened as the battle for the island dragged on into early 1943. "There were ringworms all over our bodies from jungle rot and sleeping on the wet ground," Foster said. "I remember gathering up dog tags (military identification tags) from our dead." To make matters worse, a Japanese pilot would fly over every night in an archaic warplane with an engine that sounded just like a sewing machine. "We called him Sewing Machine Charlie," Foster said. "You just had to take a machete and hack your way through the jungle there, it was so thick."

After the battle for Guadalcanal finally ended in February 1943, Foster's unit was sent back to New Zealand for rest and reorganization for a few months before being shipped to the central Pacific to take Tarawa atoll from the enemy that November. The beaches there had coral reef and barbed wire, which ripped open the bottoms of many of their landing boats.

"We couldn't land close to shore and we lost a lot of the first wave of men because of this." Foster said. "When we finally landed, I immediately started cleaning my pistol but the firing spring popped off and landed in the ocean, so I just threw the pistol away and grabbed a rifle off one of the dead marines. On Tarawa, Foster experienced his second close call of the war as his squad advanced across the island from their foxholes and toward a pile of old 55-gallon oil cans. "I leaned over and heard a shot," Foster said. "It was one of my fellow squad members who was watching out for me and shot a Japanese soldier hiding in the oil cans." On Tarawa, the Marines discovered the Japanese had constructed concrete pillboxes and fortifications that were interconnected by underground tunnels. "We had to shoot directly into the holes to get them," Foster said. "They would move from one spot to another and seemed to pop up everywhere. We finally began pushing them to one end of the island where our planes started bombing them."

"Sometimes the island's sand was so soft that many of the bombs hit and didn't explode," Foster said. Toward the end of the battle, Foster got hit by either shrapnel from a U.S. bomb or by enemy fire and received a deep flesh wound in his shoulders. A wound for which he got a Purple Heart. "At the time we didn't have any real medical provisions so I was just got bandaged up and had to keep fighting.

After Tarawa, Foster's unit was sent to Hawaii for more rest and reorganization during the next few months, which gave him time to recover from his wound as well as help the rest of the division recover from malaria. Foster"s unit was then shipped to the Marianas Island chain to land on Saipan in June 1944. "I was in the first wave that landed and as we came in, there was a terrible tidal wave," Foster said. "Over half our battalion was lost."

He said he saw a entire amphibious assault craft disappear under the wave with one of his best friends on board. But Foster later found out that a U.S. Navy destroyer picked the man up alive out of the ocean. But the landing also killed half of Foster's immediate six man squad. "Mortar shells were falling both in front of us and behind us," he said. "We became engaged in a battle for survival and we were spread really thin as we advanced." As he took shelter in a bomb crater, Foster looked around and noticed that two of the three men still with him were dead and the third was badly injured.

"As the shots from the enemy continued to pour down on us, I manned that 30-caliber gun and fired it with all I had," Foster said. "The next morning there were 40 dead enemy soldiers laying all around me and one had a grenade in one hand and a bayonet in the other and had died only three feet from me.

"As the shots from the enemy continued to pour down on us, I manned that 30-caliber gun and fired it with all I had," Foster said. "The next morning there were 40 dead enemy soldiers laying all around me and one had a grenade in one hand and a bayonet in the other and had died only three feet from me.

The battle to secure the island lasted until late August 1944 but by this time, most of the Marines had malaria so bad they had to establish a tent city with a base hospital specifically designated to treat the illness. "One night we were ordered to leave our tents and lay on the ground with our helmets faced toward the wind," Foster said. "We were in the main force of a typhoon and we had to grab trees to keep from getting blown away.

At age 22, Foster found himself to be one of the "old timers. "While reorganizing on Saipan, I noticed that I knew fewer and fewer of the men that I fought with," he said. "Many of those that I had started the war with had been killed on Guadalcanal, Tarawa and in that tidal wave, in the typhoon and in the battle on Saipan."

Foster's next assignment was taking Tinian, an island which neighbors Saipan, but by this time, Foster and most of the rest of the unit had malaria to the extent that they had to be sent home to recuperate shortly after taking that island.

After arriving in California in October 1944, Foster called his high school sweetheart Janette Rankin. "I called Janette and we happily cried for an hour," he said. "I guess I spent a whole month's pay on that call." Foster married Janette Rankin Nov. 25, 1944, after which the couple moved to Oceanside, Calif., where Foster trained boot camp recruits in Judo and knife fighting for the rest of the war. He was discharged May 13, 1946, and the couple moved to Texarkana that August. They have lived there ever since.

"In war you have experiences you never dreamed you would have and you go places you never dreamed you would ever go," he said. "It's not hard to get close to God when danger is all around you and wanting to get home and marry your girl helps you survive too"

This story by our Grandfather

Back to Wayne's Regiment

Back to EMWS

This page hosted by GeoCities

Get your Free Home Page

Get your Free Home Page