The Fens of England are a sizeable area of flat, highly fertile agricultural land spanning South Lincolnshire, Mid and North Cambridgeshire and West Norfolk. The whole area was once marsh with small tracts of higher ground allowing some permenant human settlement. Through human endevour the region was resculptured.

Primitative drainage attempts occured as early as Roman times. It is still a contentious issue as to whether Car Dyke, which extended from Lincoln to Cambridge was primarily for navigation or drainage. However it is unlikely that the Romans had any kind of region wide drainage system, but rather that any drainage was of a very localised nature.

Human influence to small degrees occasionally had more wider impacts. For instance the people of Littleport in 1292 constructed a small drainage channel that connected the waters of the Upper Great Ouse, which at the time flowed towards Wisbech from Littleport, to the waters of the Little Ouse which along with the Wissey and Nar were the only waters to flow to the outfall at King's Lynn. This small step enacted a full scale change in the hydrology and allowed King's Lynn to eventually become the sole outfall of the Ouse.

Some valuable drainage work was enacted in the 15th century by Bishop Morton who gave his name to Morton's Leam an artificial channel between Peterborough and Guyhirn that increased the drainage capaity of the Nene. It was not until the 17th century that full scale drainage of the wider Fens became a feasible target.

|

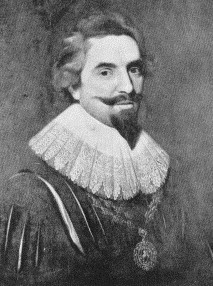

Real progress on fen drainage did not come until the expertise of the Great Dutch Engineer Sir Cornelius Vermuyden was employed. He was born in St Maartensdijk, on the island of Tholen in the Netherlands in 1595 and his services were not only used in the Fens but other low-lying and marshy areas such as Hatfield Chase in South Yorkshire, for which his was knighted by Charles I on January 6th 1629. A project to be financed by thirteen 'Adventurers' as well as the Fourth Earl of Bedford, began in 1634 with the successful obtaining of a charter from Parliament allowing them to drain the peat part of the Fens, the Bedford Level. The Gentlemen Adventures were; Sir Miles Sandys, Lord Edward Gorges, Sir Robert Bevill, Sir Phillibert Vernatt, Anthony Hamond, Andrews Burrell, Earl of Bullingbrooke, Sir Robert Heath, Sir William Russel, Sir Thomas Tyringham, Doctor Sames, Samuel Spalding and Sir Robert Lovatt. Vermuyden, being the most eminent drainage expert, and disputing criticism by rival engineers such as Jan Barents Westerdyke, drained the Bedford Level under an arrangement by which he would receive about 38,500 ha of the drained lands. During the 1630s nine major drainage cuts were built, ranging in distance from 2 to 21 miles. The main work of this time was Old Bedford River which was completed in 1637. It should be noted that this cut was not his own idea but had first been advocated in 1605. During this period Vermuyden also cut Sam's Cut from Feltwell to the Ouse, Sandall's Cut near Ely, Bevill's Leam from Whittlesey Mere to Guyhirn, Peakirk Drain from Peterborough Great Fen to Guyhirn, New South Eau from Crowland to Clow's Cross, Hill's Cut near Peterborough, and also made improvements to Morton's Leam and Shire Drain. Vermuyden drained the area twice since dykes were broken by Parliament in 1642 during the Civil War in order to stop a Royalist advance.

The period of the Civil War not only allowed much of the previous works to decay, but also showed there was much work still to be done. Vermuyden, now working under Cromwell, set to work on the Bedford Level again in 1649 and the New Bedford River was cut at this time. It runs almost parallel to the original (Old) Bedford River at about 0.5 miles east. It took waters of the Great Ouse from Earith to Denver Sluice (near Downham Market). While the New Bedford River was something of a diversion from Vermuyden's original plans, it is equally the case that the necessity to build it came about through not being able to build his planned Cut Off Channel that would have linked the Little Ouse, Lark and Wissey, than any fault in his original plans. Labour in the 1650s was provided partly by Scots prisoners from the Battle of Dunbar as well as from Dutch prisoners following Blake's victory over Van Tromp. At this time Forty Foot Drain (also known as Vermuden's Drain) was cut, which gave Ramsey Forty Foot its name. Other works by Vermuyden in this period were Downham Eau, Tong's Drain, Thurlow's Drain, Moore's Dran, Stonea Drain near March, Hammond's Eau near Somersham and Conquest Lode between Yaxley and Farcett. In all about 120,000 ha were converted into some of Britain's most productive agricultural land, through this scheme. Drainage was mainly through the force of gravity in the 17th century. However as the peat dried up it sank to levels often below sea level and so pumping had to be administered. Firstly by windmills then steam engines and the electric powered pumps of present. While the exactities of the drainage system have changed, the majority of Vermuyden's engineering feats remain and are still an important part of the drainage system of the area.

Much criticism of Vermuyden greatly benefits from hindsight for instance in 1877, Mr A Taylor claimed,

'Vermuyden began badly, progressed ignorantly, and finished disastrously. These are strong words, but they are the honest outcome of long and practical acquaintance with the subject. If there was one fact more prominent than the rest it was that the interests of the whole Level were one and inseperable, but he...divided the Bedford Level into three portions.'

and he continues,

'How can it be shown that they should be set at variance with one another like a trio of mongrels over a meat biscuit? Yet such has been the disastrous result.'

This criticism refers to Vermuyden's division of the Bedford Level into North, South and Middle. In a similar way Skertchley writing in the 19th century wrote:

"He put asunder that which Nature had joined, and divided the Bedford Level into three portions...whose common interests were then made to clash to a degree which none but the hereditary occupiers can adequately estimate."

However its is ridiculous to suggest that this division in anyway suggests Vermuyden was unaware of the interconnectedness of the local hydrology. L.E. Harris states,

"[Vermuyden] was convinced that all parts of the Level were interdependent."

Vermuyden's purpose in dividing the Level was solely to decide to which outfalls areas of land were to drain. Any subsequent lack of co-ordination between the three levels due to administrative and financial barriers cannot be blamed on Vermuyden.

Similarly Skertchley in 'Fenland Past and Present' suggested that Vermuyden's drainage methods were moulded by his own vanity;

'the main object Vermuyden had in view was to show how much better he could drain land than nature could, by doing all in his power to abstract the wealth of water from her works and pour it into his own.'

Westerdyke had a similar disagreement with Vermuyden's methods. He had favoured achieving more rapid discharge of water through deepening existing rivers and embanking them. However Vermuyden did not disagree in principle,

'but in thee case of the Great Fenns, I cannot advise to go altogether in such a way.'

His objection was therefore on practical grounds that the soil available for embankments would be inadequate and the general level of maintenance that would be required. Vermuyden also immitated nature in his use of Washes that followed the same model as the valley bottom in an upland river.

It has been a constant of drainage engineering that the new generation would criticise the previous generations and then carry out schemes worthy of just as much later criticism. For instance the early 18th century engineer Thomas Badeslade published a book in which he criticised Vermuyden, Westerdyke, Dodson, Lord Gorges, Chichley, Kinderley and Perry, only for his own efforts to join the list later. Critics of Vermuyden also didn't seem to always do their own original research. L.E. Harris noted this:

"Writers such as Wells, Miller and Skertchley...based their views more on the expressed opinions of others than on their own knowledge and reasoning."

Other writers who were able to put Vermuyden's work into its historical context were much less scathing, H.C. Darby for instance in 'The Draining of the Fens' states that any failures of Vermuyden's scheme:

'was due, in great measure, to factors over which he had no control.'

he also reminds us,

'We must not forget that he partially effected an important drainage amid great difficulties. He laboured before a host of conflicting rights, and under a great load of vested interest.'

Another regular criticism of Vermuyden was his oversight in not dealing with the state of the outfalls. Skertchley was a notable critic on this front. However, Vermuyden states clearly in his "Discourse" of 1642:

"The outfalls of Wisbech and Welland will utterly decay...if they should remain as they are now"

Hence he was fully aware of the problem. He put forward a proposal to unite the Welland and Nene to one outfall. The likely reason for this never coming about was almost certainly down to the tight financial restrictions the Adventurers put him under. Similar schemes to unite outfalls in the Fens were put forward by Nathaniel Kinderly in 1751 and Sir John Rennie in 1839.

In a similar way Vermuyden's proposal to build a cut off channel that would link the Wissey, Lark and Little Ouse also seems to have been a casualty to lack of capital. The absense of such a cut contributed greatly to the sometimes inadequate nature of the drainage of the South Level. In 1953 a new flood relief scheme was enacted which had as its major feature a cut off channel almost identical to that of Vermuyden's plan of more than 300 years prior. It could be argued that by the very nature of his works such a channel was the only option. But that fact that Vermuyden's idea now provides adequate drainage shows that in many ways he was ahead of his time.

Viewers from the 19th and 20th centuries far too easily saw it as an obvious oversight that Vermuyden did not foresee the shrinkage of drained peat. However, while Colonel Dodson in 1665 criticised Vermuyden, he believed the problem was the river 'bottoms' rising and not that the surrounding land was sinking so clearly it was far from clear to anyone in the 17th century. J. Korthals-Altes writing 'Sir Cornelius Vermuyden' in 1925 states

'it was unfortunate that a man with practice in Zealand had to find the solution for the drainage of the English Fenland and that an experienced engineer from North Holland such as Jan Adriannszoon Leeghwater, with his great knowledge of marshland drainage, had not that oppurtunity.'

Leeghwater was a pioneer of the use of windmills for pumping water for drainage, a system that was eventually adopted in the Fens through neccessity. It is possible Leeghwater could have devised a better plan for the drainage of the Fens. But it is much less likely that he would have had the determination to battle through opposition from locals, massive political turmoil and heavy constraints of finance in order to carry out such a scheme in the way Vermuyden did. Korthals-Altes goes on to say,

'It is easy enough in these times...to criticize Vermuyden's work; but undoubtedly Vermuyden was the pioneer of drainage works in England."

Vermuyden died in Westminster in October 1677.

Vermuyden is by no means the only drainage engineer as he dealt essentially with the Great Ouse basin, it was the Earl of Lindsey for instance, who was responsible for cutting a 24 mile channel from the River Glen near Bourne to Boston which drained significant land where point gaining places such as Bicker Gauntlet, Donington Westdale and Pinchbeck North Fen. Similarly Earl Fitzwilliam constructed the North Forty Foot drain, albeit with little success in terms of draining Holland Fen, in 1720. Vermuyden was undoubtedly the most prolific and notable. L.E. Harris wrote,"He was in no way responsible for the desire, the urge, to drain the Fens." But this is surely testament even more to Vermuyden as it shows he was the man to do it where others had failed.

Another man, Sir John Rennie, could potentially have been an extremely influential figure in the shaping of the Fenland area. He was born in 1794 and was the leading British civil engineer of his period. Among his many notable works were the completion of London Bridge (originally designed by his father) and for which he gained his knighthood as well as the Plymouth Breakwaters, the Royal William Victualling Yard in Plymouth and Horkstow suspension bridge over the River Ancholme. He was also one of the pioneers of floating foundations for buildings using this idea for a warehouse in the West Indian Docks of London. He also carried out many land drainage works. However, it was his proposal in 1839 of the reclamation of much of the southern part of The Wash that makes him so important to Fenland Village Collectors. If his proposal had been carried through areas which are sands at low tide and submerged at high tide like Old South, Herring Hill and Breast Sand would be high-grade agricultural land. Further, there would be additional settlements on these lands, perhaps a further three Holbeachs, Gedneys and Suttons or maybe the extra Terrington required to make it a settlement group. Unfortunately, Rennie's proposal was not adopted, nor were later and similar reclamation proposals by the Lincs Estaury Company in 1851 or Schoenfeld in the 1930s, and it is clearly to the detriment of the area that this was the case.

Today, when there is a massive food production surplus in the European Union, where climate change threatens all low lying areas and where wetland habits are becoming rarer and rarer, it seems inconceivable that the draining of the Fens would take place today. Further it is very likely that the Fens in their natural state would now consitute a national park that greatly surpass that of the Norfolk Broads in sheer size and habitat variety. However such constraints through industrialised agricultural production and globalisation have not been around for long. Further the window on when drainage was desirable spans a great period. It is therefore seems equally inconceivable to suppose drainage of the Fens might have been averted, even if the brilliance of Vermuyden, Rennie and others was not avaliable.

Unlike many areas people might consider to be more 'pretty', the Fens have the great quality of being instantly recognisable. The South Downs, Mendips, Chilterns or Cotswolds may have minor distingusing features, but the Fens are strikingly unique. In one respect this uniqueness can be put down to the way in which an area that is so rural, can yet be devoid of anything in the way of wildlife or generally concieved rural qualities. Jonathon Meades in Even Further Abroad said of the Fens, "Nothing here is natural. The earth, whos potency everyone for miles depends on, is as stiff with chemicals as an East German woman athlete.'. Similarly with regard to the lack of hedgerows and areas not under agricultural explotation he said: 'All Britain would look like this if the agri-bis had its way. This is what happens when commerce is untempered by civilisation, which is an urban virtue.'

But the uniqueness of The Fens is not solely through negative aspects. There is a low population density due to the large expanses of arable land between settlements makes for low amounts of traffic away from major roads. Another noticable feature when out on the Fens is the amount of sky visable, a virtually uninterrupted view to the horizon can be achieved in all directions and views of many miles can be gained from vantage points on the Fen edge such as at Keal, Thurlby or south of Ramsey. The Fens have always been a tranquil area, it was for this reason the monastries and Abbeys in places such as Crowland and Ely developed, the tranquility remains despite the transition from bog to high grade arable land.

It should also be remembered that there are few areas in Britain which have escaped human influence, Britain's natural vegetation is temperate forest, in the Fens this human influence has simply been particularly poignant. It cannot be disputed that environmental damage has not been done but as the great Charles Kingsley once said:

"Gone are the ruffs and reeves, spoonbills, bitterns and avocets... Ah well at least we shall have meat and mutton instead, and no more typhus and ague."

By Andrew Titman of the Multiple Fenland Village Collecting Society.