(708)301-1594

Open 11 am-4 pm Tuesday through Saturday Closed Sunday and Monday webmistress                   |

Family-operated shelter helps homeless animals find new owners

Reprinted from The Sun/Homer Glen/Lockport/Lemont, Wednesday November 14, 2001

Reprinted from The Sun/Homer Glen/Lockport/Lemont, Wednesday November 14, 2001By Susan Frick Carlman, STAFF WRITER

The tiny calico pads up to the edge of its cage, mewing in a high pitch that can come only from a small kitten. Against the back wall of the small but clean pen, its foster mother is busy nursing three other wee calicos. She growls menacingly, warning a visitor to keep her distance from the hapless little feline. The kitty - being nourished by the big tabby because its own mother was run over by a car - is adorable, but the visitor passes on adopting it.

In an adjacent room, Howard's leash is snapped onto his collar and the shepherd-hound mix is led out of his pen. Across the way in their own pens, Lady, a schnauzer, and Shelly, a collie mix, explode into a chorus of furious barking, seeming to ask "Hey! What about us?" Their lament is for naught, however; after just a few minutes Howard is led back into his pen. It isn't the right mix.

Every day, Tender Loving Care Animal Shelter connects homeless animals with families prepared to care for them. Fortunately, the successful unions are frequent.

The Homer Glen facility is run by a board of directors and staffed by three members of the same family, two other paid employees and several dozen volunteers. The shelter takes in dogs and cats - as well as guinea pigs, rabbits, snakes, turtles and the occasional goat - and cares for them until someone comes along who is willing and able to give them a good home. It almost always operates at capacity.

"It seems like as soon as we adopt one out there's another one waiting to come in," says Janine Carter, who with her husband, Dennis, and a half-dozen other animal lovers founded the nonprofit shelter more than 27 years ago.

The Carters are indisputably animal people. The family and other staffers are champions of humane treatment and tireless advocates for the creatures that have no voices of their own. They consider each prospective pet owner with great care before releasing an animal from the shelter.

Dennis Carter Jr., known as Denny, has worked at the shelter for most of his 33 years.

"I always tell people, 'We're not placing animals in homes. We're trying to place people with good pets,'" he says.

It can be difficult to remain diplomatic with some of the people who give up their pets - and some of those who want to take them.

"It's actually harder to deal with a lot of the people than the animals," Janine says.

Sometimes owners kick their dogs as a way of bidding them farewell when they drop them off at the shelter, she says. The shelter recently won a court case initiated by a would-be dog owner. He sued after he was refused a puppy that he intended to keep outdoors year-round. In another instance years ago, the shelter took in a horse after it was ridden into a bar on New Year's Eve. The rescue wasn't soon enough; the animal soon died from hypothermia.

"You do the best you can, and then you go on to the next one because there are always others who need your help too," Janine says.

Often people just don't know any better, and it is not always their fault. That's how many of the critters wind up at TLC.

"Unfortunately, a lot of times, especially with exotic pets, people don't get the proper instructions for caring for them when they buy them," Janine says.

Often an animal's original owners never learned how to care for the pet. Denny says he sees a lot of Labradors between 6 months and 1 year old.

Often an animal's original owners never learned how to care for the pet. Denny says he sees a lot of Labradors between 6 months and 1 year old."That's when they become a teen-ager and most people give up on them," he says.

Many people are too busy to commit to giving a dog the time and attention it needs.

"I think people want a quick fix. They want it to be easy," Denny says. "You have to work with them every day when they're young. ... It's like having another kid, really. They get happy. They get sad. They get tired. They get angry."

In some cases circumstances change, forcing people to give up pets.

"A lot of times it's not a fault of (the owners). A child might have an allergy, or there's been a divorce, or the expense has become too much, or the caregiver has died," Janine says, although she notes that one family who gave up a pet because their daughter was allergic wound up having the child treated for depression after the animal was gone.

The older Dennis says the claim of allergy problems is sometimes a mask for people who decide to doff the pet-owner role for other reasons.

"There are legitimate reasons, and I understand that. But for so many people, that's just a convenient excuse," he says. "They're tired of them, like an old pair of shoes."

Animal instincts

The Carters are keenly attuned to the psyche of domestic animals because they've always had four-legged friends. Dennis' father, Sylvester Carter, established the Hinsdale Humane Society and ran it during the 1950s and 1960s. Dennis also served at the helm of the suburban shelter for a time and also at South Suburban Humane Society. His brother George Carter owns and operates Katering Kennels in Lemont.

The Carters are keenly attuned to the psyche of domestic animals because they've always had four-legged friends. Dennis' father, Sylvester Carter, established the Hinsdale Humane Society and ran it during the 1950s and 1960s. Dennis also served at the helm of the suburban shelter for a time and also at South Suburban Humane Society. His brother George Carter owns and operates Katering Kennels in Lemont.Janine, Dennis and their four children have always had lots of animals in their Downers Grove home. They have all spent much of the past three decades at TLC.

"It was a tough go to get this place to where it is today," Dennis says. "We didn't go on vacations, so our kids spent their summers here. It just gets in your blood."

Denny says that even when his grandparents had one of the first houses in their part of Downers Grove decades ago - having to haul their water in from a source down the street - there were always animals.

"They had chickens and turkeys and geese, all kinds of stuff," he says. "And with my grandfather working at the Humane Society, any time he found something nice he'd bring it home."

The tendency apparently is passed down. The Carters' youngest child, 16-year-old Corey, helps at the shelter on Saturdays. He often wants to bring one of the animals home, Janine says.

Denny says he's content with the three dogs, four cats, two birds, one guinea pig and one thoroughbred horse with which he and his wife, Gayle, who works at an animal hospital, share their Lockport home. (The horse actually has more appropriate accommodations nearby.) He derives enough satisfaction from being a surrogate parent to the several dozen animals staying at the shelter at any given time. He keeps a scrapbook filled with photographs of all the pets that have spent time in the shelter over the years before finding new homes.

Denny says he's content with the three dogs, four cats, two birds, one guinea pig and one thoroughbred horse with which he and his wife, Gayle, who works at an animal hospital, share their Lockport home. (The horse actually has more appropriate accommodations nearby.) He derives enough satisfaction from being a surrogate parent to the several dozen animals staying at the shelter at any given time. He keeps a scrapbook filled with photographs of all the pets that have spent time in the shelter over the years before finding new homes."At least once a week there's about 50 I want to take home. But as long as I'm here I'm happy because it's like they're my pets," says Denny, who scrubs the pen of each of his temporary pets every morning.

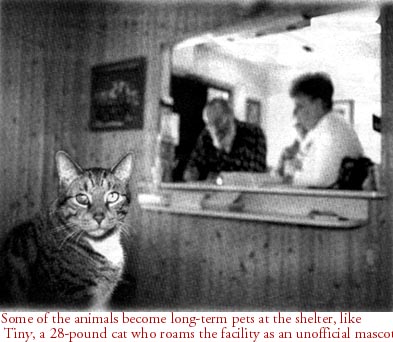

Some of the animals are long-term pets, essentially an extension of the family. Spazz, aka Tiny, a 28-pound tabby cat with one green eye and one orange one, roams the shelter after hours before heading back into his pen, ready for the day's visitors. Heaven, a docile rottweiler left at the shelter, spends most of her days curled up on the floor of the front office.

Creature comforts notwithstanding, the work has its challenges. Dennis often runs into lingering misconceptions about animal shelters.

"The worst thing is that a lot of people think shelters are nothing but killing places and that the people who work in them are these mindless, heartless, cruel people," he says. "I've been in this business all my life, and I've never met anybody who was heartless, mindless or cruel.

"Everyone who's in this is in it because they love animals. You couldn't do this every day if you didn't."

Revolving door

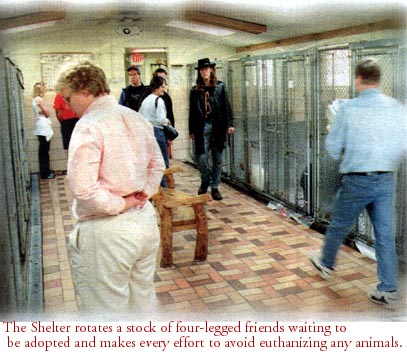

Most of the creatures don't spend much time at the shelter. The facility tries to avoid euthanizing animals and has fairly good success finding homes for most of them. But the ending is not always happy.

Most of the creatures don't spend much time at the shelter. The facility tries to avoid euthanizing animals and has fairly good success finding homes for most of them. But the ending is not always happy."Lately there's been a run on very old animals, (age) 11 on up," Janine says. "Either the owners are moving, or their lifestyle has changed, or the animals are too old or they have some other reason why they don't want to care for them anymore. We tell them their chances for adoption are virtually zero."

In many cases the former owners call after a few days to see if the animal has found a home, Denny says. If they learn that there's little likelihood of an adoptive family showing up, sometimes they'll return to reclaim the pet. But if there has been a behavioral or health problem with the pet, the shelter normally doesn't hear from the owners again.

Saturdays are the best days for the shelter and its tenants.

"This place is mobbed on Saturdays with people wanting to adopt," Janine says.

There is more room for the crowd than there used to be, thanks to an expansion last year that added more people space, some skylights and a "getting to know you room" where prospective owners and the animals can spend some quiet time together.

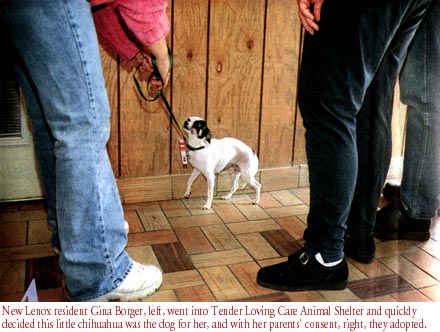

Sometimes there isn't a good match. If the staff members do not believe the animal will be treated well by the prospective new owner, they just say "no." But most of the time that isn't necessary.

"It's the families that come in here with a couple of kids and they find a pet, or you get a 65-year-old lady who finds a 10-year-old dog and takes him home. Those are the ones that make it all worthwhile," Denny says.

His dad concurs.

"When somebody walks out of here with a happy adoption, you just can't believe how great that feels," he says.

The shelter's extensive Web site, created by one of the volunteers and scattered with paw prints, has helped publicize the facility. A quarterly newsletter also keeps the animals' friends updated on the latest goings-on.

The shelter's extensive Web site, created by one of the volunteers and scattered with paw prints, has helped publicize the facility. A quarterly newsletter also keeps the animals' friends updated on the latest goings-on.The expenses of running the shelter are considerable, and sometimes it's all but impossible to cover expenses. Janine says TLC has lost $50,000 so far this year. The cost of operation runs about $250,000 annually. Revenue comes from a variety of sources, including fund-raising events such as car washes and craft shows; the fees collected for taking in and adopting out the animals; and monetary donations.

"Every shelter, every humane society has to have a group of contributors who offer ongoing support," Dennis says. "It's the nucleus that keeps TLC alive."

The facility isn't able to offer benefits to its employees, and they aren't likely to get rich from the work. That doesn't seem to matter when you've got animals in your blood.

"I do it because I love my father and I want to be just like him. And he did it because he loved his father and wanted to be just like him too," Denny says. "I don't do it for the money. I do it because I think my dad's the greatest guy on the face of the earth - and my mom too."

Contact STAFF WRITER Susan Frick Carlman at (815) 439-7528 or scarlman@scn1.com.

11/14/01