Featured Author

Dinah Craik (1826-1887)

Dinah Maria Mulock was born in Stoke on Trent on 20th April, 1826. The first of 3 children born to Dinah (née Mellard) and Thomas Mulock - her brothers Thomas and Benjamin following in 1827 and 1829. At the time of her birth Dinah's father was a nonconformist, fundamentalist, evangelical preacher ruling over a chapel built for him in Stoke where the Elect were railed off from the unsaved! A description of the type is provided in The Head of the Family (1851) in the character of John Forsyth:

Dinah Maria Mulock was born in Stoke on Trent on 20th April, 1826. The first of 3 children born to Dinah (née Mellard) and Thomas Mulock - her brothers Thomas and Benjamin following in 1827 and 1829. At the time of her birth Dinah's father was a nonconformist, fundamentalist, evangelical preacher ruling over a chapel built for him in Stoke where the Elect were railed off from the unsaved! A description of the type is provided in The Head of the Family (1851) in the character of John Forsyth:

"Apostle-like he still looked, but the softness of St John was changing into the stoniness of St Peter. His eyes had a fierce light - the enthusiasm that might become fanaticism...He seemed ready to dash out his opinions like firebrands, little caring where they alit. If such incendiaries get among God's harvest, they burn up wheat and tares together...The doctrine of love was merging into the doctrine of fear. He was less the tender shepherd, softly calling his sheep into the fold, than the threatening pastor, who would fain drive them in thither whether they chose to go or not."

However, most of Dinah's pre-teen years were spent living in her mother's birthplace, Newcastle under Lyme as a result of her father's fiery, unstable nature and his growing debts - he was reportedly committed as a pauper lunatic in the 1830s. Here she seems to have enjoyed playing with the other children in the neighbourhood free from too much parental supervision. Her mother had started a school during this time and by the time she was thirteen the young Dinah had been installed as her assistant - not an experience she seems to have relished much. In Mistress and Maid (1862) she talks of, "that monotonous daily round of school labour," declaring that teaching is a gift and seen as such chiefly by those who have it not!

In 1839, Dinah's maternal grandmother died leaving her mother a legacy on the strength of which Thomas moved the family down to London. However, the money was placed in a trust fund so that the principal could not be touched and only the interest used so that Dinah and her brothers would receive the legacy intact. In a weak moment Thomas Mulock agreed to this but seems to have spent much of the rest of his married life trying to break its terms. The sisters in Mistress and Maid (1862) are described as moving to London at the same period and some of the impressions described must have been felt by the Mulock family on their arrival in the Metropolis:

"They...felt the life of it; stirring, active, incessantly moving life;...Nothing struck Hilary more than the self-absorbed look of passers-by: each so busy on his own affairs, that,...for all notice taken of them, they might as well be walking among the cows and horses in Stowbury field.

Poor old Stowbury! They felt how far away they were from it when a ragged, dirty, vicious looking girl offered them a moss rose bud for 'one penny, only one penny;' which Elizabeth...bought, and found it only a broken off bud stuck on to a bit of wire."

On the 1841 census, Thomas Mulock put his occupation down as "Literary", but it is unlikely he published very much. Despite the constant money worries life living in Earl's Court Terrace had its entertaining side. Thomas Mulock became friendly with Charles Mathews, the manager of Covent Garden, who on occasion let the family use a box at the theatre and introduced them to actors and comedians. In The Head of the Family (1851) Dinah Mulock describes the pleasures of the theatre with Ninian Graeme's visit to the opening of his brother's play:

On the 1841 census, Thomas Mulock put his occupation down as "Literary", but it is unlikely he published very much. Despite the constant money worries life living in Earl's Court Terrace had its entertaining side. Thomas Mulock became friendly with Charles Mathews, the manager of Covent Garden, who on occasion let the family use a box at the theatre and introduced them to actors and comedians. In The Head of the Family (1851) Dinah Mulock describes the pleasures of the theatre with Ninian Graeme's visit to the opening of his brother's play:

"There are few more pleasurable excitements than that attending the first night of a new play - well acted, with a good-natured, appreciative audience. Even if Ninian had had no fraternal stake in the matter, he would have entered warmly into the interest of the night...as the play went on, the woman's genius drew him out of himself once more...She wielded the power which a great tragedian can wield over the highest moral consciousness and most refined emotions of the soul.

Whatever the individual man may be, mankind when assembled in masses is always alive to the highest ideal of human virtue. In the drama especially - that is, the heroic drama, the noblest form of theatrical representation - this instinct never fails. The thronged house was hushed to silence, thrilled with awe, melted into pity. Many women were in tears - nay, here and there, some sturdy man was seen with quivering features, half-yielding to, half-fighting against, the strong emotion. Young and old, rich and poor, ignorant and refined, were subdued, as if they had but one heart, and this woman held it in her hand.

The curtain fell...Ninian woke as out of a trance. On his mind, fresh and unused to such impressions, the effect was overpowering...Over all fell the calm which belongs to that sphere whither the great poet and actor can together lift us, when even sorrow becomes serene, and death itself appears sublimated into inexpressible peace.

So Ninian felt...with a long, deep, sigh, he threw off the enchantment. But his mind had somewhat changed - he no longer so deeply lamented over Rachel and her calling. To be an actress - and such an actress - was not altogether an unworthy destiny."

She also got to know some members of the literary world, including Mrs S C Hall who invited the young Dinah to soirées where she met authors and artists. This must have helped her later when she started out on her quest to fulfil her vocation as an author.

By 1842 Mrs Mulock's health had begun to fail and Dinah had to take over the running of the house. In 1844 Dinah and her mother departed for Staffordshire with some intentions of starting another school, leaving Thomas and the boys in London. As Dinah comments in Young Mrs Jardine, "'Honour thy father and thy mother' is a command nobody doubts. 'Love thy father and thy mother' is a different thing, for love cannot be commanded," and later in the novel a character declares, "Drunkenness, dissoluteness, anything by which a man degrades himself and destroys his children, gives his wife the right to save them and herself from him, to cut him adrift like a burning ship, and be free...Pity her lot, if you will, but to ignore it, to accept it and submit to it, above all, to let the innocent suffer from it - never!...if I were she, I would defy the law; I would hide myself at the world's end, change my name, earn my bread as a common working-woman, but I would save my child and go.'" Thomas was sinking further and further in to debt and on the 17th April, 1845, one of Mrs Mulock's brother-in-laws wrote to another one, "Mr. M. will in all probability go through the Insolvent Court; he wants to avoid it by getting his wife's money, but the trustees are firm in withholding it."

On 3rd October, 1845, Dinah's mother died and by all accounts Thomas then deserted the family. Possibly this was to avoid his debtors and/or the indignity of going through the Insolvents Court. Certainly the young Dinah Mulock seems to have been scarred by her early experience of living in a family always in debt, where the spectre of creditors was a constant threat. Debt and its tragedies loom large in just about everything she wrote. In The Head of the Family (1851) she shows how the debts of a father have a deep impact on his child as she begins to run his house for him,

"'You see, I knew nothing of money-matters,' said she, helplessly. 'I tried to learn, and to be papa's housekeeper, as I am now. At first he gave me money every week, and I did very well, and paid everybody. And then he said I must send the bills to him, and he would pay them. But papa is not very particular, and thinks tradesmen ought to wait. At last he grew angry whenever I asked him for money; and all these people used to be coming to me, and I could give them nothing but promises and kind words. They were very rude to me sometimes, but I was only sorry; it was so hard for them. Once I went and sold some of my ornaments to pay my dressmaker, because she was too poor to wait until papa's money came in...Perhaps I am very wrong in telling these things, but, oh! I have so suffered!'"

"'You see, I knew nothing of money-matters,' said she, helplessly. 'I tried to learn, and to be papa's housekeeper, as I am now. At first he gave me money every week, and I did very well, and paid everybody. And then he said I must send the bills to him, and he would pay them. But papa is not very particular, and thinks tradesmen ought to wait. At last he grew angry whenever I asked him for money; and all these people used to be coming to me, and I could give them nothing but promises and kind words. They were very rude to me sometimes, but I was only sorry; it was so hard for them. Once I went and sold some of my ornaments to pay my dressmaker, because she was too poor to wait until papa's money came in...Perhaps I am very wrong in telling these things, but, oh! I have so suffered!'"

The father in the story, Mr Ansted is finally arrested by the sheriff's officers and is persuaded to go through the Insolvent Court and depart for America. A number of the young men in her novels fall in to debt and suffer ever after. The young scapegrace Ascott Leaf who seems to care for nobody but himself, expecting his aunts or his godfather to rescue him every time. He is arrested by the sheriff's officers and his aunts discuss what is to be done -"Hilary started up...'We can not help him. He does not deserve helping. If the debts were food now, or any necessaries; but for mere luxuries, mere fine clothes; it is his tailor who has arrested him...I would rather have gone in rags!..It's mean, selfish, cowardly, and I despise him for it. Though he is my own flesh and blood.'"

There is a history of profligacy in the family passing down from the sisters' father Henry Leaf:"[Johanna] closed her eyes...as if living over again the old days - when Henry Leaf's wife and eldest daughter used to have to give dinner parties upon food that stuck in their throats, as if every morsel had been stolen; which in truth it was, and yet they were helpless, innocent thieves; when they and the children had to wear clothes that seemed to poison them...when they durst not walk along special streets, nor pass particular shops, for the feeling that the shop people must be staring, and pointing, and jibing at them, 'Pay me what thou owest!'"

A ring that is a family heirloom has to be sold. This gets Ascott released from prison, but his debts are so large that they have to apply to his godfather for money to pay the rest. Ascott then sinks so low as to turn the cheque from one of £20 in to one of £70 and when this is discovered to run away thus leaving his aunt Hilary to work for some years to pay off his debts. He is discovered towards the end of the book having changed his name, a very chastened individual working as an assistant to a chemist and druggist living on £20 a year and sleeping under the shop counter, but he is a better man for it. Francis Charteris in A Life for a Life is a similar if more black-hearted wastrel who eventually does go through the Insolvent Court, but although a reformed character afterwards he is a broken man. However, others such as Edmund in The Head of the Family (1851) and Roderick in Young Mrs Jardine (1879) are basically good men who are rescued before they sink too far. Roderick is simply not used to working to a budget, "Poor fellow! he had got into what women call 'a regular muddle;' like many another man who, neglecting or despising the small economies which result in large comforts, and regardless of the proportion of things and the proper balance of expenditure, drifts away into endless worries, anxieties, sometimes into absolute ruin, and all for want of the clear head, the firm, careful hand, and, above all, the infinite power of taking trouble, which is essentially feminine."

Just as Hope Ansted does in the earlier novel, Roderick's wife, Silence has to sell her jewels to pay the tradesmen.

Left to themselves Dinah and her two brothers had to make their own way in the world. In The Ogilvies (1849) she describes various family ties thus:

"Ties of blood do not necessarily constitute ties of affection...The parental or fraternal bond is at first a mere instinct...a link of duty; but when, added to this, comes the tender friendship, the deep devotion, which springs from sympathy and esteem, then the love is made perfect, and the kindred of blood becomes a yet stronger kindred of heart. But unless circumstances, or the nature and character of the parties themselves, allow opportunity for this union, parent and child, brother and sister, are as much strangers as though no bond of reationship existed between them.

Thus it was with Eleanor and Hugh...they had always loved one another with a kind of instinctive affection, yet it had never grown into that devotion which makes the tie between brother and sister the sweetest and dearest of all earthly bonds, second only to the one which Heaven only makes - perfect, heart-united marriage."

The money held in trust for the three was not available until they came of age which meant, in Dinah's case, another two years. Her brother, Tom, gave up art school for life as a sailor and Benjamin studied to become a civil engineer. Dinah wrote constantly - essays, short stories for children and adults and eventually novels. She and Benjamin lived in lodgings off the Tottenham Court Road in an area she describes in the novel she was writing at the time, The Ogilvies:"...surely the dreariest place in all London is the region between Brunswick Square and Tottenham Court Road! There solemn wealth sets up its abode, and struggling respectability tries to creep under its shadow, in many a dull, melancholy street; while squalid poverty grovels in between, with its miserable courts and alleys, that make the sick and weary heart to doubt even the existence of good."

The Ogilvies, her first full length adult novel was published in 1849, and dedicated to her mother. By this time, however, she had suffered another tragedy in the loss of her brother Tom who, falling from his ship whilst in dry dock died from his injuries on 12th February, 1847. At one point in the novel the character of Philip is portrayed wandering the National Gallery, a place that Dinah perhaps visited with Tom the would-be artist since she goes on to reminisce:"And turning for a moment from our story to the individual memories which its progress brings, let us linger in the place whither we have led Philip Wychnor; a place so full of old associations that even while thinking of it we lay down our pen and sigh. Good, careless reader - mayhap you never knew what it was to lead a life in which sorrow formed the only change from monotony, a life so solitary that dream-companions alone peopled it, nor how, looking back on that dull desert of time, one remembers lovingly the pleasant spots that brightened it here and there - how in traversing the old haunts our feet linger, even while we contrast gladly and thankfully the present with the past...seeing also, living faces that were once beside us there - some, most dear of all on earth - others on whom we shall never more look until we behold them in heaven."

The struggles of a young writer trying to get their first novel published are depicted in a much later novel, Young Mrs Jardine (1879). The eponymous heroine suggests writing to her husband as a profession because, "Authorship costs nothing but pen, ink, and paper." The manuscript is carefully tied up and sent off in naive hope of success,

"Celebrated authors are usually treated with courtesy and kindliness by eminent publishers...but unknown and amateur authors who rashly send their MSS. to busy firms, unto whom their small venture is a mere drop in the bucket, an unconsidered nothing, received and laid indefinitely aside, do not always meet the same consideration."

Roderick Jardine having failed to get his novel published goes back to basics with a "solid" article and begins to make his way as an author not starting, "with a picturesque and imaginative view of his own deservings, and how they were to be appreciated; he worked heartily at whatever came to his hand to do, and consequently he did good work." Dinah herself continued to write constantly. Her brother Benjamin departed for Australia in 1850 and at some point in the early 1850s she moved in to lodgings with another young girl, Frances Martin. From a well to do family in Richmond the latter later founded the Working Women's - now the Frances Martin - College.

As her novels began to sell Dinah Mulock moved to Camden and then to a house in Hampstead where she hosted parties for her literary and artistic friends. Mrs Oliphant wrote of her at this time:

"She was a tall young woman with a slim pliant figure, and eyes that had a way of fixing the eyes of her interlocutor in a manner which did not please my shy fastidiousness. It was embarrassing, as if she meant to read the other upon whom she gazed, - a pretension which one resented...But Dinah was always kind, enthusiastic, somewhat didactic and apt to teach, and much looked up to by her little band of young women."

She sold the copyright of her first three novels outright to the publisher, Chapman & Hall. However, as her third novel, The Head of the Family (1851) went in to its sixth edition she began to feel slightly cheated, writing to Edward Chapman:

"Do you think that out of the profits of all that you could spare some addition to the one hundred and fifty pounds you gave me? - I know it is not a right - and yet it seems hardly unfair...I have not been able to work this winter – and may not be able to finish my fireside book for months – so that it becomes important to me to gather up all I can – My head is tired out with having worked too hard when I was young - and now when I could get any amount of pay, I can't write."

Mrs Oliphant introduced her to the director of Hurst and Blackett who agreed to publish what became her most well known work, John Halifax, Gentleman on generous terms. With its publication in 1856, her fame and reputation were secured and most of her later works were published as being "by the author of John Halifax, Gentleman". As her work continued to become more successful she became more assertive in her bargaining and despite writing in her A Woman's Thoughts About Women (1858):"...who, on the receipt of a lady's letter of business - I speak of the average - would henceforth desire to have our courts of justice stocked with matronly lawyers, and our colleges thronged by 'Sweet girl-graduates with their golden hair?'

As for finance, in its various branches - if you pause to consider the extreme difficulty there always is in balancing Mrs Smith's housekeeping-book, or Miss Smith's quarterly allowance, I think...you need not be much afraid lest this loud acclaim for 'women's rights' should ever end in pushing you from your stools, in counting-house, college, or elsewhere..."

she, herself, was very astute about her money and business affairs. Mrs Oliphant asserts that Henry Blackett used to turn pale "at Miss Mulock's sturdy business-like stand for her money" and talked of these encounters, "with affright, very grave, not able to laugh"! As a measure of her ability, at one point she was commanding two thousand pounds for the copyright of a story - a far cry from the £150 she received for her first novel.

This access of wealth left Mrs Oliphant rather rueful at having introduced her to her particular friend, Mr Blackett and thus as she states in her Autobiography allowing Dinah to "spring thus quite over my head...Success as measured by money never came to my share. Miss Muloch[sic] in this way attained more with a few books, and these of very thin quality, than I with my many." This smacks a little of sour grapes, but the two did remain friends at a distance, brought together again by sorrow when Dinah wrote to her on the death of Mrs Oliphant's nephew Frank in 1879, who she had brought up as a son, Mrs Oliphant replying,

"Thank you most warmly for your sympathy. It is good to have an old friend to think of one in one's trouble. We have seen little of each other for many years, but we will not forget how long it is since we first joined hands, young and fresh to life..."

When Dinah asks for any commissions in Italy before a proposed trip in 1884, she is asked to visit the graves of Mrs Oliphant's husband and daughter as the bereaved author remembers "as if it were yesterday you sitting by my bedside holding that miracle of Heaven, my firstborn."

In 1861 the first seeds of a major change in Miss Mulock's life were sown. On January 14th, 1861, there was an "alarming accident" on the London and North Western Railway to the Scotch mail train as it approached London. There were only five passengers left on the train occupying one carriage. Between Pinner and Harrow stations several carriages came off the line. One of the passengers, as the Times for the 15th January reports, was "Mr Craik, a young man 24 years of age, son of the Rev Dr Craik, of Glasgow...When the passengers were taken out of the carriage...Mr Craik was found to have sustained serious injury...[he] was removed to the Euston Hotel...[and] attended by Mr Shelding, the railway company's surgeon. He was found to have received a...fracture of one of his legs, and of so dangerous a character that it was deemed advisable, with a view to save his life, to amputate the limb, an operation which was performed later in the day by Mr Haynes Walton of St Mary's Hospital...In the course of the day the father and mother of Mr Craik were, at his request, telegraphed to come to London". For some reason George Craik was taken to the house of Dinah Mulock in Hampstead to recuperate following the loss of his leg - possibly because of her friendship with his uncle of the same name. The young George, his mother and sister were still with her when the census was taken in the Spring of that year, although he returned to Scotland once he was fully fit.

In 1861 the first seeds of a major change in Miss Mulock's life were sown. On January 14th, 1861, there was an "alarming accident" on the London and North Western Railway to the Scotch mail train as it approached London. There were only five passengers left on the train occupying one carriage. Between Pinner and Harrow stations several carriages came off the line. One of the passengers, as the Times for the 15th January reports, was "Mr Craik, a young man 24 years of age, son of the Rev Dr Craik, of Glasgow...When the passengers were taken out of the carriage...Mr Craik was found to have sustained serious injury...[he] was removed to the Euston Hotel...[and] attended by Mr Shelding, the railway company's surgeon. He was found to have received a...fracture of one of his legs, and of so dangerous a character that it was deemed advisable, with a view to save his life, to amputate the limb, an operation which was performed later in the day by Mr Haynes Walton of St Mary's Hospital...In the course of the day the father and mother of Mr Craik were, at his request, telegraphed to come to London". For some reason George Craik was taken to the house of Dinah Mulock in Hampstead to recuperate following the loss of his leg - possibly because of her friendship with his uncle of the same name. The young George, his mother and sister were still with her when the census was taken in the Spring of that year, although he returned to Scotland once he was fully fit.

In the early 1860s, Dinah was granted a £60 annual pension from the Civil List in consideration of her services to literature - a pension that was passed on regularly to new and struggling writers. Ben at this time was flitting in and out of Dinah's life having returned from Australia, tried photography as a profession and been unable to settle anywhere for very long. It is unclear whether he was a manic depressive, an alocholic or a drug addict but early in 1863 he apparently appeared at the house afraid he was going mad and begging Dinah to take care of him. She watched him constantly until her own health broke down and he then had to be placed in an institution. Unfortunately in the June of that year he was knocked down by a vehicle and killed whilst running away from the place. Following this latest bereavement she left Hampstead for Wemyss Bay, on the Clyde in Scotland - a country that seems to have held a special place in her heart. She had spent several summers there and her love for the place is reflected in many of her novels. In The Head of the Family (1851) the family in question are from Edinburgh and much of the action of the story takes place here with a short digression for a holiday to the "shores of the Clyde" describing the area thus, "the blue Clyde, the shadowy giant-peaks of Arran, the Holy Loch, and the purple Argyle hills." In A Life for a Life (1859) the noble Doctor Max Urquhart, the hero of the novel betrays his nationality by declaring, "There is nothing for warmth like a good plaid," Hilary's upright lover in Mistress and Maid (1862) is from Ayrshire, with a "grave, heavy-browed, somewhat severe face...sharp, strong Scotch features," the setting of A Noble Life (1866) is in and around an "ancestral castle, in the far north of Scotland," whilst Young Mrs Jardine (1879) is also set mainly in the Highlands.

During this time in Scotland her relationship with the Glasgow accountant, George Lillie Craik progressed to a declaration of marriage and a wedding held in Bath on 29th April, 1865, followed by a move to furnished rooms in a farmhouse near Glasgow. However, the couple were enticed back to London by the offer of a partnership to George Craik from the publisher Alexander Macmillan. For a time they lived in Chilchester Lodge in Wickham Road, Beckenham. Emily and Ellen Hall were near neighbours and became friendly with the couple. In August 1866 Emily wrote in her diary, "She lives in all the simplicity of a house without bell or knocker...so I had some difficulty in gaining ingress. She is tall and must have been pretty...Now her hair is nearly white...a small comely and not old face. Her manner, like her writing, is gentle and quiet - very pleasing but perhaps a little wanting in energy or animation." She later described George Craik as, "quiet, with a plain humorous face, and a sententious way of speaking." In June 1868 Dinah called on Emily to let her know that they liked the area so much that they had bought a piece of land in Shortlands and were going to build a house using Norman Shaw as the architect.

Before the house was built, however, there came another great change to her life. As the Bromley Record for 1869 reports,

"Beckenham – a Baby found – As a gardener named Williams was on his way to work early on New Year's morning, he discovered a female child, eight or nine months old, lying behind a stack of bricks, the poor little creature was nearly dead from cold and exposure, but by kind and careful treatment it soon recovered, and was taken to the Locksbottom Union. The information soon spread through the village, and two benevolent ladies, Miss Wilkinson, of Shortlands, and Mrs Craik, of Chilchester Lodge, went to the Union House to see it, and resolved to rescue the little stranger from its pauper home, and adopt it between them. Judging from its appearance and dress, the child had been well cared for up to within a short time of its being found. The above named ladies had it christened on Sunday, the 10th at Shortlands Church, and gave it the name of Dorothy, and since then Mrs Craik has taken it home, to bring it up as her adopted daughter. After every possible enquiry not the slightest evidence has been discovered concerning the child."

From her writings it seems clear that Dinah had always longed for a child. In Mistress and Maid (1862), for example, the "Maid", Elizabeth's engagement comes to nothing, but in the baby of the household, to whom she is a surrogate mother, she finds contentment, "To Elizabeth...[little Henry] was a perfect revelation of beauty and infantile fascination. He filled up every corner of her heart. She grew fat and flourishing, even cheerful." Another surrogate mother in the story is an elder sister. Miss Johanna Leaf had taken her half-sister, Hilary from her "dead mother's bed" and "From that solemn hour...[the baby] became Johanna's one object in life. Through a sickly infancy...her sole hands washed, dressed, fed it; night and day it 'lay in her bosom, and was unto her as a daughter.'" In A Noble Life (1866), Helen Bruce returns to Scotland with her dying husband, broken by poverty and debt, virtually unrecognisable and yet she has a child, "...that instant was heard from the inner room...the sharp, waking cry of a very young infant. In a moment Helen started up; her whole expression changed. And when, after a short disappearance, she re-entered the room - with her child, who had dropped contentedly asleep again, nestling to her bosom - she was perfectly transformed. No longer the plain, almost elderly woman, she had in her poor worn face the look - which makes any face young, nay, lovely - the mother's look." Her last adult novel, King Arthur: not a Love Story (1886), centres around the adoption of a baby boy by a recently married middle-aged couple. In this novel the villagers say of the adopting mother that she is "uncommon kind" and "hoped she would be rewarded for her 'charity'". She, however, declares,

From her writings it seems clear that Dinah had always longed for a child. In Mistress and Maid (1862), for example, the "Maid", Elizabeth's engagement comes to nothing, but in the baby of the household, to whom she is a surrogate mother, she finds contentment, "To Elizabeth...[little Henry] was a perfect revelation of beauty and infantile fascination. He filled up every corner of her heart. She grew fat and flourishing, even cheerful." Another surrogate mother in the story is an elder sister. Miss Johanna Leaf had taken her half-sister, Hilary from her "dead mother's bed" and "From that solemn hour...[the baby] became Johanna's one object in life. Through a sickly infancy...her sole hands washed, dressed, fed it; night and day it 'lay in her bosom, and was unto her as a daughter.'" In A Noble Life (1866), Helen Bruce returns to Scotland with her dying husband, broken by poverty and debt, virtually unrecognisable and yet she has a child, "...that instant was heard from the inner room...the sharp, waking cry of a very young infant. In a moment Helen started up; her whole expression changed. And when, after a short disappearance, she re-entered the room - with her child, who had dropped contentedly asleep again, nestling to her bosom - she was perfectly transformed. No longer the plain, almost elderly woman, she had in her poor worn face the look - which makes any face young, nay, lovely - the mother's look." Her last adult novel, King Arthur: not a Love Story (1886), centres around the adoption of a baby boy by a recently married middle-aged couple. In this novel the villagers say of the adopting mother that she is "uncommon kind" and "hoped she would be rewarded for her 'charity'". She, however, declares,"Charity! She laughed at the word. Charity had nothing at all to do with it. A child in the house! it was a joy incarnate, a blessing unspeakable, a consolation without end...That morbid self-contemplation, if not actual selfishness, which is so apt to grow upon old maids and childless wives - upon almost all women who have arrived at middle age without knowing the 'baby fingers' waxen touches,' which press all bitterness out of the mother's breast - vanished into thin air...Susannah's empty heart was filled, her monotonous life brightened; the future (she was only just over forty, and had a future still) stretched out long and fair; for it was not her own - it was her son's."

Dorothy, the "gift of God" was adopted by both Dinah and George. Emily Hall, again in her diary, wrote, "Mrs Craik is satisfied herself that it's a lady's child...She has become so fond of it that she added, 'But I don't care who was her mother.'"

In the summer of 1869 the family moved in to the newly built "Corner House" at Shortlands, referred to by Mrs Craik as her "house of books" because it was paid for out of the proceeds from her writing. Looking at the census for 1871, it is interesting, considering her opinions about caring for servants as human beings, to see that the housemaid, Mary Bonner, aged 22, had been with Dinah since the 1861 census. In June 1888, R R Bowker wrote an article for the American Harper's New Monthly Magazine in which he describes an earlier visit to the Corner House,

"Her home...was altogether delightful...It was set in sunny gardens, where two country roads crossed, and on that side of the house which faced the main garden was a cozy recess in the brick wall, called 'Dorothy's Parlor,' built for the out-door play-house of the little adopted daughter who made sunshine in the home, and used often in pleasant weather for a work-room by Mrs Craik. Within it was built into the wall the legend, 'Deus haec otia fecit' (God made this rest), which years ago she selected as the motto for her home, should she ever build one, with on either side the initials of her husband and herself. In the mantel of the pleasant dining-room were wrought the mottoes, "East or West, hame is best," and "Give us this day our daily bread"; but the shrine and home-room of the house was the long, pleasant drawing-room, part music-room, part library, filled with books and pictures, where the mistress of the house was seen at her best."

She seems to have enjoyed her life in Bromley as Edwin Davies, a former resident, reminisced in 1936. He mentions a "Spelling Bee" held at St George's National School in the Bromley Road in aid of the “Cottage Hospital” where there were about 40 competitors who each paid 2s. 6d as their fee. Two money prizes were offered. Among the competitors were Mrs Craik, Mr Cockerel of the Coal Merchant firm, and Davies. The evening opened with vocal and instrumental music, items of which were also given during the evening. Eventually only Davies and Dinah were left in the competition. Davies was asked to spell Britzska but said Britska, leaving out the z so had to stand out leaving Mrs Craik with first prize. Each of the competitors gave their money awards to the Hospital fund. Davies also reports that on wet and bad days during school sessions, Mrs Craik frequently went and took the children home in her carriage.

Of her later fiction, one of the most endearing books she wrote was the children's story, The Adventures of a Brownie as Told to My Child (1872) in which the "sober, stay-at-home household elf" causes all sorts of mischief playing pranks on "disorderly [and] slovenly folk," helping the children pick cherries, tormenting the grumpy gardener and leading the chicken's ducklings to a magic pond! Towards the end of her life she published what amounted to two holiday diaries in the English Illustrated Magazine; An Unsentimental Journey Through Cornwall and An Unknown Country, ie Ireland. In the former she gives a wonderful description of the Cornwall of the early 1880s where the reader is taken with Mrs Craik, her two young charges and for much of it the obliging Charles and his horse and carriage around the Lizard, down to Penzance, Land's End and back again via Tintagel over the course of two weeks, meeting various characters along the way, including, amongst others, the "famous" Mary Mundy who kept an Inn, John Curgenven with his tales of wrecks, an execrable wind band ("All our sympathy with our fellow-creatures, our pleasure in watching them enjoy themselves, our interest in studying human nature in the abstract, nay, even the picturesqueness of the charming scene, could not tempt us to stay. We...put our fingers in our ears and fled."), and a retired fisherman who was now a collector and seller of sand with his troop of donkeys. The Times of 1887 says of the second book, "Any one wondering what there is to see of Ireland...would do well to obtain [it]...Mrs Craik and her party - for she evidently was the leading spirit of the expedition - spent several weeks exploring the coast region of the north and north-west of Ireland, a region rarely visited by tourists...Many who read the pleasantly-written narrative...will be tempted to follow her daring example."

In October 1886, after a visit from the author, Emily Hall declared, "She has become very large and suffers from rheumatism. Her doctor insolently informs her that her maladies arise from old age. She is just 60!" Miss Hall also mentions that Dorothy is "engaged to be married to a sort of connection of Mrs Craik's...He is one of ten children, so there is not much money on his side and Mrs Craik considers...that it is wisest to wait for two years, until she is 21 - the other 26." However, wedding plans were already well in hand in 1887 at the time of Dinah Craik's sudden death from heart failure on Wednesday 12th October. She had apparently earlier declared to a friend of Edwin Davies, "Oh, that I may live to see my daughter married!" It is possible that she felt her life was drawing to a close and so allowed the wedding plans to proceed, and in fact Dorothy did marry Alexander John M'Donell Pilkington, second son of Mr Henry Mulock Pilkington, QC, LLD, of Tore, Westmeath on the 8th November that year at St Mary's, Shortlands.

Mrs Craik's obituary in the Bromley Record of November 1st, 1887, states that "To the poor of Shortlands and in the neighbourhood, her decease is a heavy loss, and probably some time will elapse ere another will be found to supply her place, and minister with so much zeal, and unselfishness to the wants of her poorer neighbours...The remains of the deceased lady were interred on the following Saturday in Keston Churchyard, within a short distance of Wilberforce's oak, in Holwood Park, where she often came to sit, and where she loved to bring her friends in order that they might be able to obtain a full view of the surrounding magnificent landscape. The polished coffin of English oak was almost hidden beneath the array of floral wreaths, sent by sympathising and devotedly attached friends. The procession numbered about thirty carriages, and proceeded at a slow pace across Hayes to Keston...The grave selected to contain the coffin was close to Mrs Bonham Carter's, and was literally hewn out of the chalk...no sooner had Mr Craik, Mr Henry Craik and the other chief mourners taken their places, than the church became so full that it was unable to accommodate the congregation, and numbers were compelled to remain in the porch or outside, exposed to the cold biting wind and occasional showers of rain. The service was conducted by the rector of Keston, Rev C H Wright, and the Vicar of St Mary's Shortlands, Rev H F Wolley. Newman's beautiful hymn, 'Lead kindly light,' was sung before the procession moved out of the church to the graveside, where the remainder of the service was read, and after the coffin had been lowered the floral tributes were laid upon it. The coffin contained the following simple inscription: “Dinah Maria Craik, died Oct 12th, 1887, aged 61."

Mrs Craik's obituary in the Bromley Record of November 1st, 1887, states that "To the poor of Shortlands and in the neighbourhood, her decease is a heavy loss, and probably some time will elapse ere another will be found to supply her place, and minister with so much zeal, and unselfishness to the wants of her poorer neighbours...The remains of the deceased lady were interred on the following Saturday in Keston Churchyard, within a short distance of Wilberforce's oak, in Holwood Park, where she often came to sit, and where she loved to bring her friends in order that they might be able to obtain a full view of the surrounding magnificent landscape. The polished coffin of English oak was almost hidden beneath the array of floral wreaths, sent by sympathising and devotedly attached friends. The procession numbered about thirty carriages, and proceeded at a slow pace across Hayes to Keston...The grave selected to contain the coffin was close to Mrs Bonham Carter's, and was literally hewn out of the chalk...no sooner had Mr Craik, Mr Henry Craik and the other chief mourners taken their places, than the church became so full that it was unable to accommodate the congregation, and numbers were compelled to remain in the porch or outside, exposed to the cold biting wind and occasional showers of rain. The service was conducted by the rector of Keston, Rev C H Wright, and the Vicar of St Mary's Shortlands, Rev H F Wolley. Newman's beautiful hymn, 'Lead kindly light,' was sung before the procession moved out of the church to the graveside, where the remainder of the service was read, and after the coffin had been lowered the floral tributes were laid upon it. The coffin contained the following simple inscription: “Dinah Maria Craik, died Oct 12th, 1887, aged 61."

Over the course of her career she fought for a number of causes, some of them highly unpopular, in her fiction:

- adoption - King Arthur: not a love story (1886)

- judging a person by their mind and not the appearance of their body - Olive (1850), A Noble Life (1866)

- love of a man and a woman is a higher duty than that towards parents - A Life for a Life (1859), Young Mrs Jardine (1879)

- marriage without love is a disaster - just about everything she ever wrote!

- married women's property rights - A Brave Lady (1870)

- right of in-laws to marry after the death of a spouse - Hannah (1872)

- servants as human beings - Mistress and Maid (1862)

This is not to say that her fiction is dull and ponderous. On the contrary it is full of life, passion and humour. Even one of her darkest novels, A Life for a Life (1859), has a wonderful scene of the two newly-weds of the story, "there was a great deal of laughing with Augustus and Lisabel - who had pushed one another ankle-deep into the pond, and behaved exactly like a couple of school-children out on a holiday..."

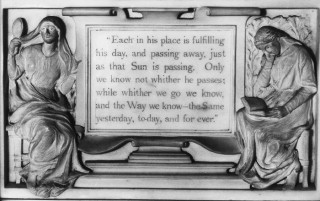

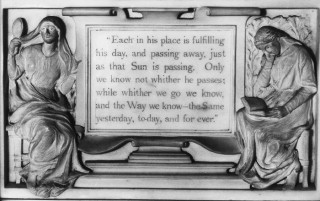

Shortly after her death a scheme for the erection of a suitable memorial of her work was started by some of those who "prized that work", the committee including Frances Martin, Clarence Dobell (in whose company she first visited Tewkesbury), Lord Tennyson (who had sent a wreath to her funeral), Robert Browning, Sir Frederic Leighton, Sir John Millais, Professor Huxley, Mr J Russell Lowell, Mrs Oliphant and Miss Charlotte M Yonge. When the Empress of Germany, Queen Victoria's daughter, heard about the memorial she, according to the Times, "at once wrote to express her great interest in anything relating to Mrs Craik, and forwarded 300 marks (£15) as her contribution." It was decided that the memorial would take the form of a marble medallion in Tewkesbury Abbey, the home of John Halifax, Gentleman. In July 1890 it was placed in the Abbey and as the Times for July 21st of that year reports,

"It is the work of Mr H H Armstead, RA, and is designed to indicate the 'noble aim of her work.' Above the cornice is placed a group illustrative of Charity; while in the architectural member is a winged laurel wreath, surmounted by an alto-relief, containing the figures of Truth and Purity. A central shield bears the quotation from 'John Halifax, Gentleman,' 'Each in his place is fulfilling his day, and passing away, just as the Sun is passing. Only we know not whither he passes; while whither we go we know, and the way we know - the same yesterday, to-day, and for ever.' A medallion portrait is contained in a circular moulding, supported by Corinthian pilasters, on which are borne the maiden and married names of the authoress, 'Dinah Maria Mulock - Mrs Craik.' The inscription on the frieze runs, 'A tribute to work of noble aim and to a gracious life.'

"It is the work of Mr H H Armstead, RA, and is designed to indicate the 'noble aim of her work.' Above the cornice is placed a group illustrative of Charity; while in the architectural member is a winged laurel wreath, surmounted by an alto-relief, containing the figures of Truth and Purity. A central shield bears the quotation from 'John Halifax, Gentleman,' 'Each in his place is fulfilling his day, and passing away, just as the Sun is passing. Only we know not whither he passes; while whither we go we know, and the way we know - the same yesterday, to-day, and for ever.' A medallion portrait is contained in a circular moulding, supported by Corinthian pilasters, on which are borne the maiden and married names of the authoress, 'Dinah Maria Mulock - Mrs Craik.' The inscription on the frieze runs, 'A tribute to work of noble aim and to a gracious life.'

With especial thanks to my mum for researching the Census information

Biographical Bibliography

- Blain, V et al. The Feminist Companion to Literature in English. London: B T Batsford Ltd, 1990

- Coghill, Mrs H (ed). Autobiography and Letters of Mrs Margaret Oliphant. Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1974

- Davies, Edwin. Materials Relating to Mrs D M Craik. 1936 (unpublished)

- Hardie, M. Bibliographic Memoir. In: Craik, D. An Unsentimental Journey Through Cornwall. Newmill, Penzance: The Jamieson Library, 1988

- Mitchell, Sally. Dinah Mulock Craik. 1983 [viewed online]

- Shattock, J. The Oxford Guide to British Women Writers. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993

- Showalter, E. A Literature of Their Own: from Charlotte Bronte to Doris Lessing. London: Virago Press Ltd, 1982

- Sutherland, J. The Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction. Singapore: Longman, 1990

- The Times online

- UK Census online

- Walker, J. Dinah Maria Craik and the "Gift of God" Bromleag March 2004: 8-11

Here are a few extracts from some of Dinah Mulock Craik's fiction

John Halifax, Gentleman (1856)

"Children, we were so happy, you cannot tell. He was so good; he loved me so. Better than that, he made me good; that was why I loved me so. Better than that, he made me good; that was why I loved him. Oh, what his love was to me from the first! strength, hope, peace; comfort and help in trouble, sweetness in prosperity. How my life became happy and complete - how I grew worthier to myself because he had taken me for his own! And what he was - children, no one but me ever knew how dearly I loved your father.

A Life for a Life (1859)

...Mr Johnston asked her how she dared think of me - me, laden with her brother's blood and her father's curse.

She turned deadly pale, but never faltered: "The curse causeless shall not come," she said, "for the blood upon his hand, whether it were Harry's or a stranger's, makes no difference; it is washed out. He has repented long ago. If God has forgiven him, and helped him to be what he is, and lead the life he has led all these years, why should I not forgive him? And if I forgive, why not love him, and if I love him, why break my promise, and refuse to marry him?"

Mistress and Maid (1863)

The ladies were all there. Johanna arranging the table for their early tea: Selina lying on the sofa trying to cut bread and butter: Hilary on her knees before the fire, making the bit of toast, her eldest sister's one luxury. This was the picture that her three mistresses presented to Elizabeth's eyes: which, though they seemed to notice nothing, must, in reality, have noticed every thing.

...Miss Leaf came forward, rather uncertainly, for she was of a shy nature, and had been so long accustomed to do the servant's work of the household, that she felt quite awkward in the character of mistress. Instinctively she hid her poor hands, that would at once have betrayed her to the sharp eyes of the working-woman, and then, ashamed of her momentary false pride, laid them outside her apron and sat down...

...Miss Leaf came forward, rather uncertainly, for she was of a shy nature, and had been so long accustomed to do the servant's work of the household, that she felt quite awkward in the character of mistress. Instinctively she hid her poor hands, that would at once have betrayed her to the sharp eyes of the working-woman, and then, ashamed of her momentary false pride, laid them outside her apron and sat down...

"Is her name Elizabeth?"

"Far too long and too fine," observed Selina from the sofa. "Call her Betty."

..."We will call her Elizabeth," said Miss Leaf, with the gentle decision she could use on occasion.

The Adventures of a Brownie (1872)

There once was a little Brownie who lived - where do you think he lived? - In a coal cellar. Now a coal-cellar may seem a most curious place to choose to live in; but then a Brownie is a curious creature - a fairy, and yet not one of that sort of fairies who fly about on gossamer wings, and dance in the moonlight, and so on. He never dances; and as to wings, what use would they be to him in a coal-cellar? He is a sober, stay-at-home household elf - nothing much to look at, even if you did see him, which you are not likely to do - only a little old man, about a foot high, all dressed in brown, with a brown face and hands, and a brown peaked cap, just the colour of a brown mouse. And like a mouse he hides in corners - especially kitchen corners, and only comes out after dark when nobody is about, and so sometimes people call him Mr Nobody.

Young Mrs Jardine (Good Words, 1879)

Suddenly, through the grey, cloudy sky, the sun broke out, poured down a torrent of light, like a cataract of molten gold, into the lake, then spanned it with a bridge of rays from shore to shore.

"Oh, how lovely!" cried Roderick, and both of them, shading their eyes from the dazzling glory, stood watching it, till the descending sun, suddenly touching the verge of the mist, plunged into it and disappeared.

"Is it all ended?"

"Not quite," said Silence...Slowly a faint colour, like a blush, crept over the 'everlasting snows,' deepening more and more as it spread from summit to summit along the whole range of Alps.

"It looks as if an angel were stepping from peak to peak with a basket of roses."

Some reviews of her works

Olive (1850)

REVIEW It is a common cant of criticism to call every historical novel the “best that has been produced since Scott,” and to bring “Jane Eyre” on the tapis whenever a woman's novel happens to be in question. In despite thereof we will say that no novel published since “Jane Eyre” has taken such a hold of us as this “Olive,” though it does not equal that story in originality and in intensity of interest. It is written with eloquence and power.

The Head of the Family (1851)

GUARDIAN We have arrived at the last and by far the most remarkable of our list of novels, “The Head of the Family,” a work which is worthy of the author of “The Ogilvies,” and, indeed, in most respects, a great advance on that. It is altogether a very remarkable and powerful book, with all the elements necessary for a great and lasting popularity. Scenes of domestic happiness, gentle and tender pathos abound throughout it, and are, perhaps the best and highest portions of the tale.

Two Marriages (1867)

In these days of sensation novels it is refreshing to take up a work of fiction, which, instead of resting its claims to attention on the number and magnitude of the crimes detailed in its pages, relies for success on those more legitimate grounds of attraction which, in competent hands, have raised this class of literature to a deservedly high position.

The Laurel Bush (1877)

The Laurel Bush (1877)

HARPER'S NEW MONTHLY MAGAZINE Nothing that Mrs Mulock-Craik writes is ever weak, and the Laurel Bush...is decidedly a strong story, though in spirit and in structure just what its title-page calls it, "an old-fashioned love story." The plot is not new - the separation of faithful lovers through the mischance of a mislaid letter; the moral is not new - the strength and fidelity of real love; but a certain moral power pervades the story that makes it far from commonplace, though possessed of no characteristic features that can be epitomized in a notice.

Young Mrs Jardine (1879)

MORNING POST A book that all should read. Whilst it is quite the equal of any of its predecessors in elevation of thought and style, it is perhaps their superior in interest of plot and dramatic intensity. The characters are admirably delineated, and the dialogue is natural and clear.

Christian's Mistake (1865)

THE TIMES A more charming story to our taste has rarely been written than the narrative of the scruples and tender endurance of Christian Oakley, married to the Rev. Arnold Grey, D.D., master of St Bede's College, Avonsbridge, at the University Church, and which marriage is an incident of doubtful omen, the evil auguries of which are not entirely dispelled until the story reaches its satisfactory completion.

The charm of this story consists mainly in the delineation of character, and especially of character which is honourable or loveable, for in describing character the writer exhibits a consummate art. She invariably holds her hand at the right point. She knows when she has finished her picture, and then she leaves it. Within the compass of a single volume she has hit off a circle of varied characters all true to nature, some true to the highest nature, and she has entangled them in a story which keeps us in suspense, till its knot is happily and gracefully resolved, while, at the same time, a pathetic interest is sustained by an art of which it would be difficult to analyze the secret. It is a choice gift to be able thus to render human nature so truly and so calmly, to penetrate its depths with such a searching sagacity, and to illuminate them with a radiance which is so eminently the writer's own. A braver woman than Christian Oakley, as Miss Muloch depicts her, never existed, a gentler man than Arnold Grey is hardly possible, and they elucidate their life secret and extricate their way to a permanent understanding by a developing sympathy which is admirable in its conception, and most delicately handled in its treatment till they reach the bourne of consummate happiness.

The mistake of Christian is simply this - she marries her reverend husband, a widower, with three children, certainly without loving him, but with a tender sensitive conscience which will impel her into love, for such a man as he was, surely but insensibly. She has, however, a secret, comparatively innocent, which she withholds from him so long as circumstances do not compel its revelation, but at last she tells him (and to him it is no revelation, for he had known it already), in all the torture of its attendant circumstances, which his delicacy deters him from probing until a crisis of embarrassment brings about an unanticipated and complete explanation between them and the only offender. It was not really Christian's mistake that she had a fleeting love passage with a young man of high station, but of disreputable character - disreputable, that is, up to the date of the conclusion of the story, when he earns condonation by a somewhat tardy repentance; but Christian did, in her own opinion, commit a mistake in not making this incident known to her husband previous to the acceptance of his offer. This error preyed upon her conscience, and was a real difficulty, though unknown to her it had been thoroughly explained to her husband, and she lingered aloof in spirit from him who had otherwise entirely won her heart, and regarded herself as weak and unworthy till he himself proved to her that he regarded her conduct in the very opposite light. With this denouement comes the perfect happiness which promises to be so permanent and serene.

The mistake of Christian is simply this - she marries her reverend husband, a widower, with three children, certainly without loving him, but with a tender sensitive conscience which will impel her into love, for such a man as he was, surely but insensibly. She has, however, a secret, comparatively innocent, which she withholds from him so long as circumstances do not compel its revelation, but at last she tells him (and to him it is no revelation, for he had known it already), in all the torture of its attendant circumstances, which his delicacy deters him from probing until a crisis of embarrassment brings about an unanticipated and complete explanation between them and the only offender. It was not really Christian's mistake that she had a fleeting love passage with a young man of high station, but of disreputable character - disreputable, that is, up to the date of the conclusion of the story, when he earns condonation by a somewhat tardy repentance; but Christian did, in her own opinion, commit a mistake in not making this incident known to her husband previous to the acceptance of his offer. This error preyed upon her conscience, and was a real difficulty, though unknown to her it had been thoroughly explained to her husband, and she lingered aloof in spirit from him who had otherwise entirely won her heart, and regarded herself as weak and unworthy till he himself proved to her that he regarded her conduct in the very opposite light. With this denouement comes the perfect happiness which promises to be so permanent and serene.

While the fabric of this story is a very subtle web, though woven out of elements apparently so simple, the action is carried on in the limited circle of the household of the Master of St Bede's College, consisting of his sister and sister-in-law, his three children, a harsh and violent, though well-intentioned, nurse, a suspicious butler, and a governess who is a flirt, and who flirts inopportunely with the young baronet who had made his early court to the master's wife, and who, on the assumption that he has an influence over her which she had utterly discarded, places her for a time in very compromising circumstances. The interest of the story, apart from this, is purely domestic, and turns upon what may appear trivial incidents - such as Christian's continual efforts to perform her duties as mistress of her husband's household, and the stepmother and protector of his children. In this she is thwarted for a time by every one excepting her husband, especially by their aunts, who are highly supercilious to her, and it is only by the firmest resolution and the most admirable tact that she conquers their resistance to her beneficent domestic sway. It is surprising how much interest Miss Muloch elicits up to this point from materials so apparently trivial and restricted. Yet there lies the art in the skill and significance of the artistic touch.

After all, Christian had made no mistake in any sense, and the querulous doubt that she had so made one became a vanished and forgotten dream. The conscientious constancy, which was the keynote of her character, had given the right determination to her affections, and henceforth her happiness was fully assured from the point where the story comes to its harmonious close. We can hardly praise Miss Muloch too highly for her creation of this character; we cannot perceive that there is in any sense any ground for disparagement, and even if he tried by the standard of the Archbishop of York we should expect that even he would pronounce it a novel without a fault.

Appreciations of Mrs Craik by those who grew up reading her literature

From an article by Elsa D'Esterre-Keeling, "The Family Life - Part II. The Family in Fiction" from Girl's Own Paper, Volume 22, January 26th 1901

Some of us who were once upon a time girls can remember the first book, not avowedly a book for girls, in the case of the present writer it was – as in the case of not few others it has been – John Halifax, Gentleman by Mrs Craik (Miss Muloch[sic]). That writer, among whose earliest and best productions were The Ogilvies, The Head of the Family and John Halifax, in whose three novels, as in most of the novels that followed them, dealt with phases of home-life. The most admired of her books was (and is) John Halifax, which a Scottish writer terms “a noble story of English domestic life.” No one who has read the story will forget the description in it of the death of Muriel, the blind child. John Halifax has been reading to his children, assembled to their full number for the last time

For an hour nearly, we all sat thus, with the wind coming up the valley, howling in the beech-wood, and shaking the casement as it passed outside. Within the only sound was the father's voice. This ceased at last; he shut the Bible and put it aside. The group – that last perfect household picture – was broken up. It melted away into things of the past, and became only a picture for evermore.

Among those who are not blind to the faults of Mrs Craik, one notes in her “a too prolonged feminine softness and occasional sentimentalism.” It cannot be said that John Halifax is wholly free of these faults, but they who have faculties other than the critical will not withhold their admiration from a story which contains a strikingly beautiful picture of English family life.

From the column "The Brown Owl" by L T Meade, from Atalanta, Volume III, January 1890

It has occurred to me as I write these paragraphs month by month that I should like to say a word for some special favourites of my own in the book-world. In my day all girls read them; perhaps they do so still. In these times, however, when so much that is excellent appears quickly, and when the rush to keep up even with the current literature becomes greater year by year, the old thoughtful good books which are not exactly classics, but are nearly so, may be forgotten. I should like to remind the readers of Atalanta that new editions of these dear old writers are always appearing. It is restful and pleasant in these terribly restless days to turn to their pages. One of the most conscientious and earnest of these authors is Miss Muloch[sic], whose Woman's Kingdom is full of suggestions, of helpful thought, and all kind of good things. What a hero John Halifax used to be thought, and how keenly girls long ago sympathized with Christian in her mistakes and difficulties. There are shoals of books worth reading, but not worth buying; the lending library can supply them. But it is nice to have a volume or two of Miss Muloch on one's own especial pet shelf...

Three Poems by Dinah Craik

AMONG THE MOUNTAINS - A Remonstrance

Grey heavens, grey earth, grey sea, grey sky,

Yet rifted with strange gleams of gold;

Downwards, all's dark; but up on high

Walk our white angels, - dear of old.

Strong faith in God and trust in man,

In patience we possess our souls;

Eastward, grey ghosts may linger wan,

But westward, back the shadow rolls.

Life's broken urns with moss are clad,

And grass springs greenest over graves:

The shipwrecked sailor reckons glad,

Not what he lost, but what he saves.

Our sun has set, but in his ray

The hill-tops shine like saints newborn:

His after-glow of night makes day,

And when we wake it will be morn.

SUNDAY MAGAZINE, 1883

|

FALLEN IN THE NIGHT!

It dressed itself in green leaves all the summer long, It dressed itself in green leaves all the summer long,

Was full of chattering starlings, loud with throstles' song.

Children played beneath it, lovers sat and talked,

Solitary strollers looked up as they walked.

Oh, so fresh its branches! and its old trunk grey

Was so stately rooted, who forbode decay?

Even when winds had blown it yellow and almost bare,

Softly dropped its chestnuts through the misty air;

Still its few leaves rustled with a faint delight,

And their tender colours charmed the sense of sight,

Filled the soul with beauty, and the heart with peace,

Like sweet sounds departing - sweetest when they cease.

Pelting, undermining, loosening, came the rain;

Through its topmost branches roared the hurricane;

Oft it strained and shivered till the night wore past;

But in dusky daylight there the tree stood fast,

Though its birds had left it, and its leaves were dead,

And its blossoms faded, and its fruit all shed.

Ay, and when last sunset came a wanderer by,

Still it wore its scant robes so pathetic gay,

Caught the sun's last glimmer, the new moon's first ray;

And majestic, patient, stood amidst its peers

Waiting for the spring-times of uncounted years.

But the worm was busy, and the days were run;

Of its hundred sunsets this was the last one:

So in quiet midnight, with no eye to see,

None to smite in falling, fell the noble tree!

Says the early labourer, starting at the sight

With a sleepy wonder, "Fallen in the night!"

Says the schoolboy, leaping in a wild delight

Over trunk and branches, "Fallen in the night!"

O thou Tree, thou glory of His hand who made

Nothing ever vainly, thou hast Him obeyed!

Lived thy life, and perished when and how He willed;-

Be all lamentation and all murmurs stilled.

To our last hour live we - fruitful, brave, upright,

'Twill be a good ending, "Fallen in the night!"

GOOD WORDS, Vol IV, 1863 |

IN SWANAGE BAY

Twas five-and-forty year ago,

Just such another morn,

The fishermen were on the beach,

The reapers in the corn;

My tale is true, young gentlemen,

As sure as you were born.

"My tale's all true, young gentlemen,"

The fond old boatman cried

Unto the sullen, angry lads,

Who vain obedience tried;

"Mind what your father says to you,

And don't go out this tide.

"Just such a shiny sea as this,

Smooth as a pond, you'd say,

And white gulls flying, and the crafts

Down Channel making way;

And Isle of Wight, all glittering bright,

Seen clear from Swanage Bay.

"The Battery Point, the Race beyond,

Just as to-day you see;

This was, I think, the very stone

Where sat Dick, Dolly, and me;

She was our little sister, sirs,

A small child, just turned three.

"And Dick was mighty fond of her:

Though a big lad and bold,

He'd carry her like any nurse,

Almost from birth, I'm told;

For mother sickened soon, and died

When Doll was eight months old.

"We sat and watched a little boat,

Her name the 'Tricksy Jane,'

A queer old tub laid up ashore,

But we could see her plain.

To see her and not haul her up

Cost us a deal of pain.

"Said Dick to me, 'Let's have a pull;

Father will never know:

He's busy in his wheat up there,

And cannot see us go;

These landsmen are such cowards if

A puff of wind does blow.

"'I've been to France and back three times-

Who knows best, dad or me,

Whether a ship's seaworthy or not?

Dolly, wilt go to sea?'

And Dolly laughed and hugged him tight,

As pleased as she could be.

"I don't mean, sirs, to blame poor Dick:

What he did, sure I'd do;

And many a sail in'Tricksy Jane'

We'd had when she was new.

Father was always sharp; and what

He said, he meant it too.

"But now the sky had not a cloud,

The bay looked smooth as glass;

Our Dick could manage any boat,

As neat as ever was.

And Dolly crowed, 'Me go to sea!'

The jolly little lass!

"Well sirs, we went: a pair of oars;

My jacket for a sail:

Just round 'Old Harry and his Wife' -

Those rocks there, within hail;

And we came back. --D'ye want to hear

The end o'the old man's tale?

|

"Ay, ay, we came back past that point,

But then a breeze up-sprung;

Dick shouted, 'Hoy! down sail!' and pulled

With all his might among

The white sea-horses that upreared

So terrible and strong.

"I pulled too: I was blind with fear;

But I could hear Dick's breath

Coming and going, as he told

Dolly to creep beneath

His jacket, and not hold him so:

We rowed for life or death.

"We almost reached the sheltered bay,

We could see father stand

Upon the little jetty here,

His sickle in his hand;

The houses white, the yellow fields,

The safe and pleasant land.

"And Dick, though pale as any ghost,

Had only said to me,

'We're all right now, old lad!' when up

A wave rolled - drenched us three -

One lurch, and then I felt the chill

And roar of blinding sea.

"I don't remember much but that:

You see I'm safe and sound;

I have been wrecked four times since then -

Seen queer sights I'll be bound.

I think folks sleep beneath the deep

As calm as underground."

"But Dick and Dolly?" "Well, poor Dick!

I saw him rise and cling

Upon the gunwale of the boat -

Floating keel up - and sing

Out loud, 'Where's Doll?' - I hear him yet

As clear as anything.

"'Where's Dolly?' I no answer made;

For she dropped like a stone

Down through the deep sea, and it closed:

The little thing was gone!

'Where's Doll?' three times; then Dick loosed hold,

And left me there alone.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

"It's five-and-forty year since then,"

Muttered the boatman grey,

And drew his rough hand o'er his eyes,

And stared across the bay;

"Just five-and-forty year," and not

Another word did say.

"But Dolly?" ask the children all,

As they about him stand.

"Poor Doll! she floated back next tide

With seaweed in her hand.

She's buried o'er that hill you see,

In a churchyard on land.

LETT'S HOUSEHOLD MAGAZINE, VOL 3, 1885 | |

Incidentally...

According to Cassell's Family Magazine of 1885 a series of four Christmas cards for that year designed by Mr F Noel Paton, had verses by the author of “John Halifax, Gentleman".

I would love to read the short story A Dreadful Ghost by the author of "John Halifax, Gentleman"

Click here to see a list of her works

HOME

See other featured authors: Mrs George Linnaeus Banks, Sir Walter Besant, Rosa Nouchette Carey, Dutton Cook, Ellen Thorneycroft Fowler, Edna Lyall, Isabella Fyvie Mayo, William Edward Norris.

Dinah Maria Mulock was born in Stoke on Trent on 20th April, 1826. The first of 3 children born to Dinah (née Mellard) and Thomas Mulock - her brothers Thomas and Benjamin following in 1827 and 1829. At the time of her birth Dinah's father was a nonconformist, fundamentalist, evangelical preacher ruling over a chapel built for him in Stoke where the Elect were railed off from the unsaved! A description of the type is provided in The Head of the Family (1851) in the character of John Forsyth:

Dinah Maria Mulock was born in Stoke on Trent on 20th April, 1826. The first of 3 children born to Dinah (née Mellard) and Thomas Mulock - her brothers Thomas and Benjamin following in 1827 and 1829. At the time of her birth Dinah's father was a nonconformist, fundamentalist, evangelical preacher ruling over a chapel built for him in Stoke where the Elect were railed off from the unsaved! A description of the type is provided in The Head of the Family (1851) in the character of John Forsyth: "'You see, I knew nothing of money-matters,' said she, helplessly. 'I tried to learn, and to be papa's housekeeper, as I am now. At first he gave me money every week, and I did very well, and paid everybody. And then he said I must send the bills to him, and he would pay them. But papa is not very particular, and thinks tradesmen ought to wait. At last he grew angry whenever I asked him for money; and all these people used to be coming to me, and I could give them nothing but promises and kind words. They were very rude to me sometimes, but I was only sorry; it was so hard for them. Once I went and sold some of my ornaments to pay my dressmaker, because she was too poor to wait until papa's money came in...Perhaps I am very wrong in telling these things, but, oh! I have so suffered!'"

"'You see, I knew nothing of money-matters,' said she, helplessly. 'I tried to learn, and to be papa's housekeeper, as I am now. At first he gave me money every week, and I did very well, and paid everybody. And then he said I must send the bills to him, and he would pay them. But papa is not very particular, and thinks tradesmen ought to wait. At last he grew angry whenever I asked him for money; and all these people used to be coming to me, and I could give them nothing but promises and kind words. They were very rude to me sometimes, but I was only sorry; it was so hard for them. Once I went and sold some of my ornaments to pay my dressmaker, because she was too poor to wait until papa's money came in...Perhaps I am very wrong in telling these things, but, oh! I have so suffered!'" In 1861 the first seeds of a major change in Miss Mulock's life were sown. On January 14th, 1861, there was an "alarming accident" on the London and North Western Railway to the Scotch mail train as it approached London. There were only five passengers left on the train occupying one carriage. Between Pinner and Harrow stations several carriages came off the line. One of the passengers, as the Times for the 15th January reports, was "Mr Craik, a young man 24 years of age, son of the Rev Dr Craik, of Glasgow...When the passengers were taken out of the carriage...Mr Craik was found to have sustained serious injury...[he] was removed to the Euston Hotel...[and] attended by Mr Shelding, the railway company's surgeon. He was found to have received a...fracture of one of his legs, and of so dangerous a character that it was deemed advisable, with a view to save his life, to amputate the limb, an operation which was performed later in the day by Mr Haynes Walton of St Mary's Hospital...In the course of the day the father and mother of Mr Craik were, at his request, telegraphed to come to London". For some reason George Craik was taken to the house of Dinah Mulock in Hampstead to recuperate following the loss of his leg - possibly because of her friendship with his uncle of the same name. The young George, his mother and sister were still with her when the census was taken in the Spring of that year, although he returned to Scotland once he was fully fit.

In 1861 the first seeds of a major change in Miss Mulock's life were sown. On January 14th, 1861, there was an "alarming accident" on the London and North Western Railway to the Scotch mail train as it approached London. There were only five passengers left on the train occupying one carriage. Between Pinner and Harrow stations several carriages came off the line. One of the passengers, as the Times for the 15th January reports, was "Mr Craik, a young man 24 years of age, son of the Rev Dr Craik, of Glasgow...When the passengers were taken out of the carriage...Mr Craik was found to have sustained serious injury...[he] was removed to the Euston Hotel...[and] attended by Mr Shelding, the railway company's surgeon. He was found to have received a...fracture of one of his legs, and of so dangerous a character that it was deemed advisable, with a view to save his life, to amputate the limb, an operation which was performed later in the day by Mr Haynes Walton of St Mary's Hospital...In the course of the day the father and mother of Mr Craik were, at his request, telegraphed to come to London". For some reason George Craik was taken to the house of Dinah Mulock in Hampstead to recuperate following the loss of his leg - possibly because of her friendship with his uncle of the same name. The young George, his mother and sister were still with her when the census was taken in the Spring of that year, although he returned to Scotland once he was fully fit. From her writings it seems clear that Dinah had always longed for a child. In Mistress and Maid (1862), for example, the "Maid", Elizabeth's engagement comes to nothing, but in the baby of the household, to whom she is a surrogate mother, she finds contentment, "To Elizabeth...[little Henry] was a perfect revelation of beauty and infantile fascination. He filled up every corner of her heart. She grew fat and flourishing, even cheerful." Another surrogate mother in the story is an elder sister. Miss Johanna Leaf had taken her half-sister, Hilary from her "dead mother's bed" and "From that solemn hour...[the baby] became Johanna's one object in life. Through a sickly infancy...her sole hands washed, dressed, fed it; night and day it 'lay in her bosom, and was unto her as a daughter.'" In A Noble Life (1866), Helen Bruce returns to Scotland with her dying husband, broken by poverty and debt, virtually unrecognisable and yet she has a child, "...that instant was heard from the inner room...the sharp, waking cry of a very young infant. In a moment Helen started up; her whole expression changed. And when, after a short disappearance, she re-entered the room - with her child, who had dropped contentedly asleep again, nestling to her bosom - she was perfectly transformed. No longer the plain, almost elderly woman, she had in her poor worn face the look - which makes any face young, nay, lovely - the mother's look." Her last adult novel, King Arthur: not a Love Story (1886), centres around the adoption of a baby boy by a recently married middle-aged couple. In this novel the villagers say of the adopting mother that she is "uncommon kind" and "hoped she would be rewarded for her 'charity'". She, however, declares,