|

|

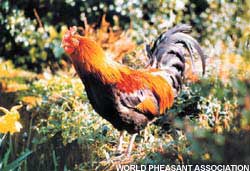

RED

ROVING FOWL |

|

| India, which

gave the red jungle fowl, the mother of all

poultry to the rest of the world, is now importing

poultry from outside and destroying its own

indigenous species. Today these unique breeds are

disappearing, partly because of neglect and partly

because of crossbreeding; about 99 per cent of all

wild populations have been contaminated by

domestic or feral chicken. But certain rare breeds

still exist and there is time to save

them |

|

POULTRY BREED

DESCRIPTION |

RED JUNGLE FOWL(GALLUS

GALLUS)

Country of

origin/range: North and northeast

India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand,

Malaysia, Cambodia, Indonesia.

Contributed genes to: All

breeds of domestic chicken

Body

weight: Cock: 672-1450 g, hen: 485-1050

g

Height: Cock: 65-75 cm,

Hen: 42-46 cm

Comb:

Single

Egg shell colour:

Brown

Feather

colour: Red-brown in neck, back

and wing; black on chest, legs and

tail

Eggs: Average of

five-six eggs in a sitting

MAP NOT TO

SCALE |

| Source:

Graphic narration of red jungle

fowl’s spread from Poultry Biology, Part I,

Chapter I: Origin and History of Poultry

Species, R D Crawford; Grzimek’s Animal Life

Encyclopedia, Van Nostrand Reinhold Company,

1987 | |

DANIEL MADHAV FITZPATRICK

AND KAZIMUDDIN AHMED

Long before the birth of Christ,

a bird, never seen before in the valley of the Blue

Nile, reached the court of the pharaohs. Neither the

architectural grandeur of the court nor the

‘gold-draped’ Pharaohs could silhouette its beauty. A

bright red comb rested regally on its head and shiny

green and red feathers clothed its body finally ending

in an eclipse plume. The Egyptians had never seen a bird

which laid so many eggs. When it crowed, they listened

with rapt attention. When it walked around the court,

everyone made way. It became a showpiece in the

Pharaoh’s court. Fascinated, they adopted the bird.

Everbody used to be shown the chicken and training camps

were set up on how to get this wild red jungle fowl

(RJF) to lay eggs.

But much before the bird reached Egypt, available

literature suggests that RJF (Gallus gallus) was

first domesticated in the twin cities of Mohenjodaro and

Harappa in the Indus valley around 2500-2100 BC. Seals

were found at Mohenjodaro depicting fighting cocks.

Various clay figurines of the fowl were also found,

including one of a hen with a feed dish. Two clay

figurines were found at Harappa appearing to represent a

cock and a hen.

While most wild animals were domesticated for meat,

in the case of RJF, which belongs to the family of

pheasants, it was for its fighting abilities. In

Bhavprakash Nighantu, a book on ayurveda by

Acharya Bhavprakash, he states that the Vedas, too,

praise the fowl for its ‘courage’. Referred to as

kukuth, it says that among the 20 qualities such

as courage that a human being should possess, four

should be acquired from the fowl alone.

The Indians were also the first to realise its

medicinal and nutritional worth. Special attention has

been paid to the bird in the ayurvedic system of

medicine also. "The fowl is a medicine in itself,"

agrees Vaidya Balendu Prakash of the Vaidya Chandra

Prakash Cancer Research Foundation, Dehradun. Rich in

minerals such as copper and iron, in course of time, the

fowl also became a welcome bribe (see box: Wonder

bird).

THE WONDER

BIRD

The red jungle fowl (RJF) is one of the

four jungle fowls found in the Indian subcontinent

belonging to the genus Gallus, the other

three being grey, Ceylon and green. It is also

know as Gallus bankiva or Gallus gallus

murghi.

RJF is distinct in its appearance. It’s

strikingly colourful plumes and a majestic red

comb gives it a regal appearance. But what makes

it unique is the eclipse plumage, which is now

used to identify the bird. According to Satya

Kumar, scientist at the Wildlife Institute of

India, Dehradun: "The shape of the plumage makes

it easier for the bird to escape quickly from

predators through undergrowths and bushes."

The male plumage and the colour of the ear

lobes differ according to the climate and

geographical location. The shade of red varies

from golden yellow to dark mahogany. There are

also some differences in shape and length of the

neck feathers among males. This divides the red

jungle fowl into five clear subspecies:

Cochin-Chinese red, Burmese red, Tonkinese red,

Indian red and Javan red. Among unique

characteristics of RJF is that it sheds its plumes

in the summer. The hen, which can lay up to nine

eggs in one sitting, has no visible comb or

wattle.

The RJF population is distributed across the

Indo-Malay peninsula. Apart from varied

geographical locations, it also lives in most

varied habitats — from rainforests to

drylands. |

|

| People

can easily mistake the red jungle fowl for a

common domestic bird and it could, therefore, end

up in the cooking pot rather than delight an

ornithologist. |

From the centre

of domestication, the fowl soon moved where trade took

the Indo-Aryans. Persia, modern day Iran, was possibly

one the first countries to receive the domestic fowl

from northwest India as part of the trade connections

between the agricultural areas of the Indo-Gangetic

plain and the Fertile Crescent. The Persians then took

it to Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq), from where it went

down to Asia Minor. In the 7th-8th century BC, it moved

further to Greece and, by the 5th-6th century BC, it had

encompassed a large area of the Mediterranean basin,

where it received special privileges and honour in the

Roman empire. The Romans considered it as sacred to

Mars, the God of war, while Plato wrote of people

cock-fighting instead of labouring.

|

What

makes it unique is the eclipse plumage, which is

now used to identify the bird. An artist’s

rendition of the red jungle fowl (below)

— Ram Kinker

Baij (Delhi Art

Gallery) |

In Egypt,

domestic fowl became firmly established under Greek and

Persian influence. Several pictorial and written

artefacts have been found in Egypt. One of them is a

rooster’s head in a mural from the tomb of Rekhmara,

vizier of Thutmose III (1479-1447 BC) at Thebes.

Discovered in 1835, the drawings appeared in several

books on Egyptian art and archaeology. The first

reproduction was in Travels in Ethopia published

in 1835. The mural depicted a procession of 50 human

figures representing many races bringing tribute to

Thutmose III. The tribute include a variety of animals

and birds. Among them was a gold image of the head of a

rooster with a pea comb and features of RJF.

The other

possible route the fowl took while travelling to many

parts of the globe is to Europe via the Black Sea

through China and Russia. Ancient Chinese documents also

indicate that the fowl was introduced in the country as

early as the 13th or 14th century BC. The rooster is one

of the 12 astrological signs in the Chinese calendar.

They also reached the Germanic and Celtic tribes before

the Christian era. They were brought to the us about 470

years ago with the European conquests.

Along with its

spread, the fowl was christened according to the local

dialect. For instance, pullet (young hen) in

Latin comes from the word pil in

Sanskrit.

|

It is said that among the 20

qualities such as courage that a human being

should possess, four should be acquired from the

fowl |

| The fowl’s diffusion rate is quite

remarkable. It has been estimated at 1.5-3

kilometres a year, similar to the diffusion rate

of technologies |

Similarly, chicken and cock comes from Sanskrit

kukuth or kukutha. Nomenclature aside,

everywhere it went, it was regarded as a special bird

(see box: Cocktale).

COCKTALE

As the red jungle

fowl started travelling across the globe, its

connections to different aspects of human life

also grew. It assumed the responsibility of

sounding the wake-up call to humans. Because of

this role, it was regarded as the Herald of Dawn

and the guardian of good over evil in Zoroastrian.

The call of the fowl means liberation from

darkness. So profound was the veneration that by

1000 BC Zoroastrianism forbade the eating of the

fowl. In Christian religious art, the crowing cock

symbolised the resurrection of Christ. It was also

the emblem of the first French Republic.

The Yoruba

people of West Africa believe that the chicken

made land on earth. As the story goes, the Sky God

lowered his son Oduduwa and a five-toed chicken

down a great chain from the heavens to the ancient

waters. Along with the chicken, Oduduwa had a

handful of dirt and a palm nut. He threw the dirt

on the water. The chicken busily scratched and

scattered the dirt all around until it formed the

first dry land on earth.

In India,

too, there are many beliefs and tales on the bird.

One among them is the story of Goddess Kamakhya

and the demon that wished to get wedded to her. He

threatened mass destruction if she refused him.

She then put a condition before him.

Underestimating the demon’s capability, he was

asked to build a temple overnight and the next

morning she would be his. The demon got down to

work and was in the process of finishing the

temple much before dawn. Seeing that her trick did

not work, she asked her trusted fowl to crow. Just

before the last few bricks were to be laid, the

fowl gave a full-throttled crow. And declared the

arrival of dawn. The temple was left incomplete

and the goddess was spared the ignominy of

marrying a demon. The temple is now one of the

most sacred pilgrimage sites and is located in

Guwahati, Assam.

These

are only a few stories about the fowl’s liaison

with deities and lesser mortals. |

The diffusion

rate of the fowl is quite remarkable. In the book,

The Chicken in America (1975), G F Carter, using

dates of first records in widely separated places,

estimated the rate to be between 1.5-3 kilometres a year

— reasonably consistent with rates of other things like

technologies and ideas. Backyard poultry became common.

Soon people started developing newer breeds with

selective cross breeding with other fowl, depending upon

their egg laying and meat yielding characteristics.

After a long period of trial and error the Asiatic, us

and English breeds of the ‘chicken’ that we have today

were finally born. All trace their parentage to RJF.

Today, it has become a source of food for a large

percentage of the world’s population. It is estimated

that around 14,000 million tonnes of chicken was

consumed in 1996 the world over. Unfortunately, in

India, the land where it was domesticated first, the

bird is almost forgotten. A recent study suggests that

there may not be any pure strains of RJF left in the

country. Worse still, nobody knows for sure because of

the lack of research on the bird that gave us today’s

‘table God’.

Birds of a feather

Is the RJF

extinct in the wild?

There are scientific

theories on the monophyletic (tracing origin to one

ancestor) and polyphyletic (many ancestors) origin of

modern day fowls. The former goes with the theory of

Charles Darwin (1868) that RJF is the sole ancestor of

all the domestic chicken. He considered RJF the sole

ancestor because, among other things, domestic fowls

mated freely with RJF and progeny from this were

fertile. The second theory says other three jungle fowl

species — Celyon, grey and green — could also have

contributed to the domestic fowl. The majority opinion,

however, goes with the former theory attributing RJF as

the mother of all domestic fowl. There are scientific

theories on the monophyletic (tracing origin to one

ancestor) and polyphyletic (many ancestors) origin of

modern day fowls. The former goes with the theory of

Charles Darwin (1868) that RJF is the sole ancestor of

all the domestic chicken. He considered RJF the sole

ancestor because, among other things, domestic fowls

mated freely with RJF and progeny from this were

fertile. The second theory says other three jungle fowl

species — Celyon, grey and green — could also have

contributed to the domestic fowl. The majority opinion,

however, goes with the former theory attributing RJF as

the mother of all domestic fowl.

If one goes by the popular belief on RJF origin, a

paper, "Genetic endangerment of wild red jungle fowl

Gallus gallus?", published in 1999 in Bird

Conservation International by two us scientists Lehr

Brisbin and A Townsend Peterson, is bad news for India

and RJF. According to the authors, RJF has been

genetically-contaminated over the years and there might

be no pure strain of the fowl left. A survey of the 745

museum specimens of the RJF suggests that

"percentagewise, about 99 per cent of captive

populations and potentially all of wild populations have

been contaminated by introgression of genes from

domestic or feral chicken".

The researchers say that this is evident from

observing the male eclipse plumage, an important

indicator of a pure RJF. Although the eclipse plumage is

somewhat observed in central and western populations, it

has not been observed in eastern populations. The

plumage is believed to have disappeared from Malaysia

and the neighbouring countries by the 1920s. In extreme

Southeast Asia and the Philippines, it is said to have

disappeared even before scientific documentation began

around the 1860s. The good news is the researchers did

find some pure stock, though dismally low scattered in

South Asia. In India and Nepal, the percentage of

specimens having eclipse plumage was calculated at 18.2

per cent and 19.4 per cent in Myanmar, Thailand and

Malaysia. Other typical characteristics that were taken

into consideration were the dusky black legs and the

lack of comb in the hen. So far, the authors have only

taken the external morphology into consideration, but at

present they are preparing to initiate deoxyribonucleic

acid (DNA) studies in collaboration with several chicken

genome laboratories.

The authors claim that the only pure RJF strains are

the ones with them. Collected from western India in the

1960s, they now number 50-100. "They have been kept

under typical avicultural conditions at several aviaries

across usa," says Peterson, who is also associate

professor and curator, Natural History Museum and

Biodiversity Research Centre, University of Kansas.

Peterson describes the species as "critically

endangered". "This is funny given that the species was

not even imagined to be in trouble prior to our work,

but it may well be effectively

|

"About 99 per cent of captive RJF

populations and potentially all wild populations

have been contaminated by domestic or feral

chicken" |

extinct in the wild... replaced by

chickens-in-jungle

fowl-clothing," he adds.

Hopeful, still

Although the researchers have given evidence on

the genetic contamination of RJF, other experts say that

the scenario is not as pitiable as portrayed by them. "I

know that there are still pure populations of red jungle

fowl in several areas," says Ludo Pinceel, coordinator

for research and education of the European Jungle Fowl

Group (EJFG), Belgium. Agrees Satya Kumar of Wildlife

Institute of India, Dehradun, "There are good stocks in

several protected areas of India like the Kalesar

reserve forest in Haryana. These stocks show many pure

RJF features." He is also optimistic that the fowl

population in Himachal Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and

Haryana have no or negligible gene contamination, but

has no scientific studies to back his claim.

There are apprehensions, however, on what "pure"

means. Given the status of poor research and

conservation, it is very hard to give correct facts and

figures. According to Rahul Kaul,

|

"About 99 per cent of captive RJF

populations and potentially all wild populations

have been contaminated by domestic or feral

chicken" |

South Asia coordinator of the World Pheasant

Association, the debate and the apprehensions will

continue till the genetic mapping of RJF is done. But

this is easier said than done. "The basic problem is we

do not have a definite DNA of a RJF that we can call

‘pure’ so we can compare other RJF DNAs. The us,

apparently, has the right markers," he says.

Although initiatives have been taken to develop

markers and study RJF genes, there are hurdles on the

way. Besides the money factor, research on genetics is

turning out to be very time consuming, says Kaul. "But

now that the issue of contamination has been raised, no

research will be complete without taking the genetic

aspects into account," he says.

| The

rooster finds a place on the walls of tribal

people’s houses |

|

There are a lot of references to the RJF in books

written during the period of the British Raj. It has

been mentioned as a favourite game bird. But that is all

about the information that is there on RJF during the

last two centuries, says Kaul. "There are a few RJF in

zoos. But the concept of record keeping or observation

of the birds is just not there. Even the origin of many

RJF in zoos is not known," he adds.

Unsafe or secure?

Amid the gloom surrounding RJF data, an

experiment in Haryana gives some

hope

According to the World

Conservation Union’s listing, the bird is safe and

secure. But it appears in India’s Wildlife (Protection)

Act, 1972, as a Schedule IV species — no hunting of the

bird is permitted. "Until now, RJF was considered as

‘not globally threatened’. But in the light of our

present knowledge, we think that ‘seriously endangered’

would be a better qualification," says Pinceel.

"Normally one should think there are enough populations

left in the huge area in which they occur, but the major

question is of purity. The problem is that there are a

lot of red jungle fowl like birds, but perhaps they are

seriously infected with domestic genes," he says.

Amid the lack of awareness and neglect of RJF in

India, there is but one effort in saving the fowl that

stands out — the captive breeding programme of RJF in

Morni Hills, Haryana, undertaken by the Haryana State

Forest Department. Started in 1991-92 with some local

stock of RJF and eggs that were collected from the

jungle, the stock is kept in an enclosure. In 1998, they

successfully introduced 14 birds in the wild followed by

seven in 1999.

Though the reason for starting the project was

not out of concern for RJF per se, now the objective has

shifted to reintroducing mature birds in the wild and

replenishing the wild stock. S K Khanna, a veterinary

specialist with the Government Poultry Disease and Feed

Analytical Laboratory, Ambala, Haryana, explains the

reason behind their objective. Habitat destruction and

consequent decrease in RJF numbers could lead to an

increase in some insect population, which make up a part

of the RJF’s diet. The Morni Hills project will thus

give a chance to scientists to study the impact of RJF

on insect population and the health of the population

living in areas where there is human-jungle interface.

They can also study the productivity and

immunoresistance capabilities of the fowl. "This is a

long-term project. To begin with, we have been slow

because of lack of technical skill and funding," says

Khanna. "But as of now, there are no studies to show

that decrease in RJF population could lead to subsequent

increase in insect population," says Kaul.

| The captive breeding

project in Morni Hills, near Chandigarh, aims to

replenish wild stocks of the red jungle fowl. So

far, it has already released 21 of

them |

|

|

According to

Satya Kumar, the Morni Hills stock is healthy and shows

all the traits that the pure jungle fowl has. "We can

say that the stock is relatively pure," he says. With a

healthy population of the RJF in the nearby Kalesar

reserve forest, the Morni Hills programme does seem to

hold some promise for research on the RJF. "We are

planning set up sub

|

"Until now, RJF was considered as

‘not globally threatened... but we think that

‘seriously endangered’ would be a better

qualification" |

centres as well and we are also trying to analyse and

clear all the proposals for research that are given to

us. As the genetic contamination issue is very important

now, we have to look into every aspect of RJF," says P R

Sinha, member secretary, Central Zoo Authority,

Delhi.

The tangri

is a considered a delicacy in India. But with the

new World Trade Organisation rules, they may not

be so for chicken breeders across the

country |

According to

Pinceel, the Wildlife Institute at Bologna, Italy, is

also working on a large World Pheasant Association

project, particularly the four species of jungle fowl.

One of the most important aims is to find a method to

recognise hybrids from RJF. But wildlife samples for

taxonomic studies are not allowed to be exported from

India. "This would somewhat slow the research work which

is in progress in various labs, because these

laboratories will miss important reference samples. It

would be important if DNA research on RJF could be

implemented in India, perhaps in collaboration with

other laboratories throughout the world," says Ettore

Randi, Pinceel’s colleague.

"There are a few RIF

in zoos. But the concept of record keeping or

observation of the birds is just not there. Even

the origin of many RIF in zoos is not

known"

— RAHUL

KAUL, Regional

Coordinator

(South Asia), World Pheasant

Association |

Meanwhile, in the

us, companies are already making headway in genetically

modifying chicken to suit market demands. Many are

worried that this may further threaten the purity of the

original fowl (see box: Fowl

play).

Fowl play

Modifying chicken to suit the palate. Is it

safe?

Breast meat is a delicacy in USA. So much so

that a company called Avigenics has decided to

genetically modify chicken into one that can give

the country’s citizens more breast meat per palate

and plate. Or to derive some medical benefit for

the pharmaceutical industry. That’s not all. It is

also thinking of copyrighting the DNA tag to

prevent anyone from using the same technology.

This they plan to do by introducing a unique DNA

sequence into the ‘new’ chicken gene.

Chicken are injected with human genes to

produce human proteins like insulin in their egg

whites (albumen). The roosters ‘created’ by

Avigenics have reportedly passed on a substance

called ‘alpha interferon’ to new generations of

chicken. Alpha interferon is used to treat

Hepatitis and some malignancies. The same

technology will be used to create chicken for

daily human consumption. Genes will be added or

removed from the chicken to yield better breast

muscles or greater resistance to diseases. The

company is also planning to make their new

transgenic chicken available to poultry breeders

as well.

Concerns have been raised about the dangers of

making genetically modified (GM) chicken. It is

reported that GM fish — the first modified animal

life meant for human consumption — are breeding

along with their natural counterparts. This is

threatening the population of the natural ones as

well as their purity. Similar things are feared

with GM chicken. Those involved in the GM chicken

experiment, however, argue that years of selective

crossbreeding have created chicken totally

different from their ancestors

anyway. |

MORE...

Why save the rooster?

Poultry mess

Blacked

Out

For the rest of the article

please refer to the printed copy of

Down To Earth

December 15, 2000 or SUBSCRIBE

HERE.

|