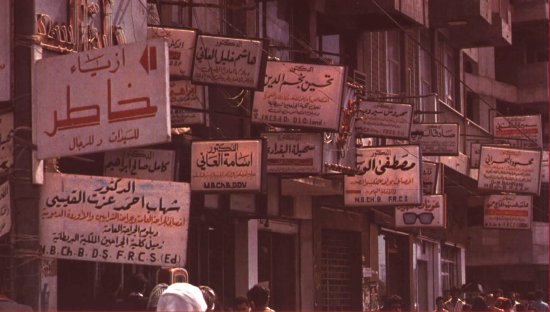

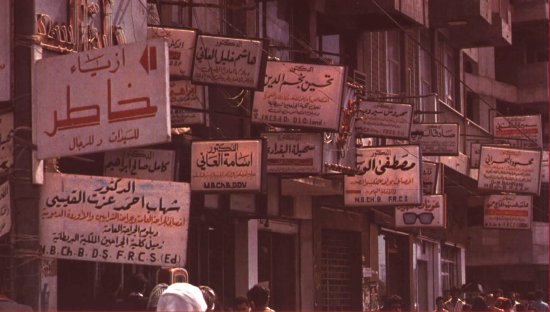

Doctor's signs in Sadoun St.

(click to enlarge)

The following is a description of Baghdad as recollected by Gavin Young from his book "IRAQ Land of Two Rivers."

It is only when we cross the big suspension bridge over the Tigris river that I get the feeling of having arrived in Baghdad. Baghdad is a real city, not just a large town, and its lights are still twinkling in the river at half past one in the morning. It is the river that 'makes' Baghdad. The Tigris, brown and swift, is the heart and soul of the City of the Caliphs.

For- one might as well declare it at once- Baghdad is not a city of stately majesty. It is not ornate and grand. It does not take your breath away like Venice, or make your heart beat a little faster like New York. It is, so to speak, a water colour, not an oil painting. It is flat and dusty - indeed, from time to time it is enveloped in maddening storms that fling dust into your room, your car, food, eyes, ears, mouth. Baghdad has muted values. It is an ancient city struggling awkwardly to be modern. If it lacks glamour, it has considerable charm. And if even the charm must be delved for, to me such delving seems worthwhile because, more than many cities, Baghdad reflects the most unusual, country that frames it. Iraq, after all, is the old, old Mesopotamia of Sumer, Babylon, Assyria, of the glorious sun-burst of the Abbasid Empire of Harun al Rashid, of Persian intrusions, and the affliction of four hundred dead years of Turkish rule. In other words, Baghdad is the still-beating heart of a former cradle of civilisation, a country as historically dramatic as Ancient Greece or the Nile Valley. (Sometimes the intrusion of history can be amusing. In the office of the Iraqi Director-General of Antiquities in Baghdad, his phone rang. 'Excuse me,' he said to me, picking it up. 'It's a call from Babylon.')

Doctor's signs in Sadoun St. (click to enlarge) |

It has to be admitted that Rashid Street and Sadoun Street, two of Baghdad's thoroughfares, lack beauty and character respectively. Yet the past nudges you even there. Along the low lines of shops and offices of Sadoun Street you see the Abbasid Palace Hotel, the Sumer Hotel, the Ur Hotel, Samiramis Travel and Tourism, the Ali Baba Restaurant. Then, Adam and Eve Fashions, and the Babylon Cinema (now showing: Richard Burton and Sophia Loren in Brief Encounter). Somewhere, too, there is the Sinbad Hotel - because Sinbad, though a sailor, was also a prosperous merchant of Baghdad. The past, like a seedy tout, sidles up to you in brash modern inscriptions on nondescript, modern facades. 'One Arab Nation with an Eternal Aim,' reads a slogan over the Baghdad Hotel, reminding one of the serious pan-Arab purpose of the ruling Ba'ath Party. And red British Leyland double-decker buses blunder hooting along the dual-carriageway like ceremonial elephants in an ill-organised procession. Down these streets the demonstrators paraded in July 1958 when the Hashemite monarchy that the British had introduced when they expelled the Turks in 1917 was overthrown and the republic was established. Iraq plunged into a decade of instability which caused a tragic disruption of her economy, educational system and development programmes.

Development, fuelled by oil revenues, is Iraq's first and urgent priority, and a visible sign of that was the mushrooming of administrative buildings. Appropriately, the Ministry of Planning, reddish and massive, dominates the Tigris' western bank. But, in general, government offices, unimpressive modern buildings, are no nearer to the Baghdad of the Arabian Nights than offices in Hamburg or London. (see also Arabian Nights in "Iraqi Mythology: Arabian Nights" of Site Index or run a search for "Arabian Nights" in the Iraq Homepage search engine).

At first you are more likely to be impressed by the confusion than by the antiquity of the city. Bits of central Baghdad are continually being pulled down and new projects take an unconscionable time to fill the gaps; as a result, much of it has a half-built look. Baghdad is a sprawling place and its population is three million and rising rapidly but it would be unfair to judge it solely by its muddled center. Baghdad consists of a dozen clamorous and pungent villages, all different; there are dignified residential complexes. And Baghdad has beauty. There is beauty in its garden suburbs, built in the last thirty years and bright with flowers- Baghdad is specially good for roses. And, however unlikely first impressions may make the happy fact, ancient Baghdad is not dead. But it is elusive.

How old is Baghdad? Babylonian bricks bearing the Royal Seal of King Nebuchadnezzar (sixth century BC) were found in the Tigris here. But whatever settlement existed then, historic Baghdad was undoubtedly founded by the second of the Abbasid Caliphs, Mansur (AD 750-775), and the name Baghdad is probably a combination of two Persian words meaning 'Founded by God'. Arabs call it 'The City of Peace'.

Exterior of Abu Hanifa Mosque |

The founding of Baghdad by Mansur came about in this way: the first Abbasid Caliph, Abul Abbas, had built a palace on the Euphrates at Anbar, but it didn't suit Mansur, who at once began to search about for somewhere more centrally placed from which to administer the new empire. Soon the site of a Sassanian village on the west bank of the Tigris caught his eye, and in · the spring of AD 762 the lines were traced out. This first Baghdad took four years to build and Mansur employed one hundred thousand architects, craftsmen and workers from all over the Islamic world. Thus came into being the famous Round City of Mansur, with double brick walls, a deep moat and a third innermost wall ninety feet high. Four highways radiated out of four gates and at the hub of everything was built the Caliph's palace with a green dome. A certain amount of judicious stealing went on: many of the stones for the palace- the center of the universe- came from the ruins of the Persian city of Ctesiphon not far away; a wrought-iron gate was taken from Wasit, another from Kufa. And a man who did more than most to help Mansur build his new city was the Imam Abu Hanifa, whose tomb you can see in Baghdad to this day.

Soon merchants built bazaars and houses round the Basra (southern) Gate and formed a district of their own called Kerkh, and this was joined by a bridge of boats to the east bank of the Tigris- where most of modern Baghdad stands in the district of Rasafa. Two cemeteries grew up- one in Adhimiya and another where Kadhimain now houses the shrines of two of the twelve Imams.

Of course, the ancient Baghdad we all read about as children is the Baghdad of Harun al Rashid, who took things over after Mansur's two sons had come and gone. His wazir was Yahya, son of Khalid al Barmaki (the Barmecide of the Arabian Nights), a Zoroastrian priest captured by a previous Caliph. He was succeeded by Jafar al Barmaki who practically ruled the empire so influential did he become. Under Harun, the lands of Islam enjoyed unprecedented glory and wealth. Baghdad became the richest city of the world. Its wharves were lined with ships- from China bringing porcelain; from Malaya and India with spices and dyes; from Turkestan with lapis lazuli and slaves; from East Africa with ivory and gold dust; and from Arabia with pearls and weapons. An Arab even in those days could cash a check in Canton on his bank account in Baghdad.

Jafar the Barmecide spent a million gold pieces on his palace and had as many slaves as the Caliph himself. His hospitality was we'll known: 'As generous as Jafar,' people said. Zubeida, Harun's wife, spent enormous sums of money on refurbishing Mecca before she travelled there on pilgrimage. Confident in his power and glory, Harun sent a message to Nicephorus I of Constantinople demanding tribute: 'From Harun, Prince of the Faithful, to Nicephorus, the Roman dog. I have read your letter, you son of a heathen mother. You will see and not hear my reply, '- and an army of one hundred and thirty-five thousand men soon followed the letter to devastate Asia Minor to the Mediterranean. Later, the Caliph Muqtadir watched emissaries from Byzantium parading before him with 'one hundred and sixty thousand horsemen and footmen, seven thousand black and white eunuchs and seven hundred chamberlains . . . and a hundred lions.'

Harun's sons started a series of destructions of their father's glorious city when they battled for the Caliphate after his death. But his victorious son Mamun's fourteen-year reign brought the city to the peak of intellectual splendour. Mathematics developed- the Baghdadis introduced the zero and the system of numbers we now use; Aristotle and Plato were translated; Mamun built an astronomical observatory where savants measured the earth's surface six hundred years before Europe admitted it was not flat. Harun had already inaugurated a free public hospital, and no doctor was allowed to practise without a diploma from a medical school.

The Baghdad of Harun, the most glorious contemporary of Charlemagne, was a nest of singing bards- of whom the most ostentatious was Abu Nawas, who was born' in AD 747 in Ahwaz, Persia, lived in Basra, became Harun's jester and poet, and died in AD 8 10. It may not have looked much like the tinsel Hollywood city of The Thief of Baghdad, but some human aspects of the 'dim-moon city' mirrored in a haunting play-poem called Hassan, written in 1922 by James Elroy Flecker, may be much nearer reality. From Hassan, a tragi-comedy ending in torture and death, emerges an awesome twentieth-century image of Harun himself. Consider his resounding titles: 'The Holy, the Just, the High-Born, the Omnipotent; the Gardener of the Vale of Islam, the Lion of the Impassable Forests, the Rider of the Spotless Horse, the Cypress on the Golden Hill, the Master of Spears; the Redresser of Wrong, the Drinker of Blood, the Peacock of the World, the Shadow of God on Earth, the Commander of the Faithful . . . The Caliph!’ Next there is Harun the patron of beauty and Harun the brutal product of a brutal age. Harun was apparently much amused by the story of a Greek from Constantinople who made act exceptionally beautiful fountain for the garden of Harun's father, the Caliph el-Mahdi. The Caliph asked the Greek if he could make more fountains as fine. 'A hundred,' replied the happy Greek. 'Impale the pig!' the Caliph shouted, and the Greek was instantly executed. So the loveliness of the fountain remained unrivalled.

Here are some extracts from the notebook of my wanderings through the older parts of Baghdad:

'A hot, heavy morning. We set out to Kerkh (west bank of the Tigris) to see what is supposed to be the tomb of Harun's wife Zubeida, built in about 1200. Zubeida is actually buried in the great golden-domed tomb-shrine of Kadhimain just north of here. (Harun himself was buried near Meshed in Persia.) But this tomb's phallic and honeycomb dome (Seljuk Turkish) is very striking and is surrounded by a cemetery that is literally over-flowing with graves, some oddly- and very recently-painted in vivid psychadelic patterns. The place has a special mystique. Behind it the steam-clouds rise from Baghdad railway station.

A shrine of ascetic Sheikh Maruf (click to enlarge) |

Nearby stands a small shrine with the remains of a holy ascetic-Sheikh Maruf- who died a few years after Harun. At its door some students smiled at us politely ('Which city are you from, sir?'), and reverently slipped off their trendy high-heeled shoes before entering it after us. (Islam thrives in Iraq~ even among the young. Wherever you go you see mosques being built, re-tiled, re-gilded, or restored. ) In brief, this shrine involves a great deal of Iraqi history... [the shrine's] origins go back to the early Abbasid period [the time of Mansur or Harun] . . . It was burned accidentally in 1067 and rebuilt by orders of Caliph al-Qaim . . . restored in 1215 by Caliph al-Nasir.. . The Mongol sacking of Baghdad in 1258 does not seem to have destroyed this mosque, for ibn Battuta [the great Tunisian traveller], who visited Baghdad in 1327, speaks of it as "standing in the quarter of the Basra Gate". The mosque has undergone several restorations including those in 1675, 1688, 1892 and finally in 1974 by the Mudir el Awqaf [Ministry of Religious Endowments] '.

All the old gates of Baghdad, except one, have disappeared. They had beautiful Arabian Nights names like Gate of the Willow-Tree, Gate of Darkness, Gate of the Moon. The one survivor is the Central or Khorasan Gate, also known as Bab el Wastani. The caravans passed through it on the Golden Road that led across Persia to Samarkand. I found workmen restoring it who told me that their yellow bricks are identical to the original Abbasid bricks they discovered in the solid structure of the old gate.

A Khadimain Bazaar (click to enlarge) |

Onto Khadimain: one of the most important monuments in Iraq or even in all Islam. A huge gilded dome on a circular drum. Four minarets. Kufic inscriptions. Canopied balconies. Glinting mirror mosaics and lustrously glazed tiles. Floors of marble. Originally built in AD 799, it is the double-tomb of the Imams Musa and his grandson Mohamed Jawad, who died in AD 799 and 835 respectively. Rebuilt by the Turkish Sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent, in 1534. Added to by the Persian ruler, Shah Abbas. A high and abominable external wall has recently been built round this famous mosque; it is of cement, painted white with wide black lines criss-crossing it. ' (see the Khadimain Mosque)

The history of Baghdad is one of unrivalled glory giving way to appalling administration, invasion, massacre, and a final decline through four hundred years of stagnant Turkish rule until the early twentieth century. The west bank of Baghdad was so badly damaged in the civil war following Harun's death in AD 806 that the Round City of Mansur completely collapsed and disappeared. People crossed the river to try again and the east bank city grew up. More civil disobedience drove the Caliph Mutasim to the extraordinary length of moving the capital to Samarra. Then, after the five hundred years of Abbasid rule, the Mongols raced down from Asia to destroy and pillage. The year 1258 heralded centuries of disaster. Hulagu, grandson of Ghenghis Khan, put the last Caliph and two of his three sons to death after a six-day siege of the capital. He slew Baghdad's poets, traders, scholars and divines. Eight hundred thousand non-Combatants are said to have been killed by the Mongols, and his soldiers stacked a mountain of jewels round Hulagu's tent. But his worst act was the destruction of the irrigation system which made the country rich. Almost overnight the golden city of the Abbasids, Baghdad, became the capital of a poor and insecure province of the I1 Khan kings called al Iraq al Arabi. Even then, the Mongols hadn't done their worst. Tamur-lane massacred thousands more Baghdadis in 1401 and destroyed mosques, houses, schools. With the coming of the Safawid Emperors of Persia things improved for a time; Shah Ismail, for example, revived commerce with Baghdad.

Sheik Abdul Qadr al Gailani Mosque (click to enlarge) |

Later came the Ottoman Sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent, who rebuilt in 1534 a number of buildings including the mosques of Abu Hanifa, Kadhimain and Sheik Abdul al Gailani, the founder of a dervish sect who died in 1253. (The Sheikh Abdul Qadr shrine owns a library of thirty-five thousand volumes, including a fine collection of Qu'rans.) But in spite of these admirable interludes of construction and restoration, they remained, generally speaking, interludes. For example, Baghdad was attacked and blockaded by the Persians alone in 1587, 1604 and 1605. And when, in 1638, Sultan Murad's vengeful soldiers entered through the Muadham Gate:

'they were so hot upon staying and plundering that they killed all they met, the whole night that this sacking lasted... In short, there were in Bagdat, one and thirty thousand pick'd and choise Soldiers, and Twenty thousand Volunteers, all of whom we have put to the Sword, not one having escaped to carry the news to the other Towns of Persia'.

Murad then energetically repaired Baghdad's mosques. From then on, Baghdad had to tolerate a succession of Turkish Pashas (governors).

Located within Baghdad is the superb Iraq Museum, an astonishing collection of antiquities- Sumerian seals and gold, Assyrian winged bulls, exquisite marble statues from Hatra, Islamic inscriptions, intricately carved doors, vividly illuminated manuscripts.

Glories less tangible than the Iraq Museum are the river Tigris - and the music of Iraq. Sometimes, usually at night, one can combine those two serenities. During the day it is enough to wander down to the water from the crowded jumble of Rashid Street (named, of course, after the great Harun)- from, say, the Ajami Coffee House, where, under old ceiling-fans, elderly men in Arab clothes or formal suits read newspapers and noisily puff hubble-bubbles in the cool dimness, and young men slap down dominoes with a noise like pistol shots among the glasses of tea and bottles of 7-Up. The sun strikes in onto the array of brass, ornate and big-bellied samovars in the entrance from a street where the red double-decker buses nose through cars and the occasional horse or camel-cart. Boys, shouting, 'Watch out, pay attention!', scurry from cats to offices balancing trays of tea and sherbet, and moustachioed Kurds stroll arm-in-arm in turbans and baggy trousers. Round the corner is the ancient Needlemakers' Wharf and the long buttressed Municipality Building (the Serai) built by a 'progressive' Turkish Governor of Iraq, both on the river. The Tigris, rolling down from Turkey, is not blue and glamorous here. It is wide and very strong and looks old. It is best seen from a boat.

The Dim Moon City (click to enlarge) |

Chugging upstream in a launch, you still see wooden cantilevered balconies and filligreed casements leaning over the water. Fine, ultra-modern buildings also line the riverbank in handsome gardens. Luckily, the new and the old sit easily together. The minarets, some elderly and brick-coloured, others turquoise-tiled, are not smothered by the bold high buildings- the dominating Telecommunications skyscraper or the Mustan-siriya University building or Medical City, or the half-built mammoth hotel rearing up between the reddish Ministry of Planning and the nineteenth-century British Embassy with its white pillars, its lovely trees and its Indian Raj look. Above Kadhimiya, look back. The golden domes and the minarets of one of Islams' finest shrines will seem to float towards you out of a sea of greenness: it is the best view of Kadhimain. The best view by day, that is. During the clear, ,cool Baghdad nights, the full magic works. The moon glints on the golden teardrop of the dome. Then you can really feel you are in what Flecker, in Hassan, described as the Caliph's 'dim-moon city'.

Bibliography:

Articles:(back to top)