CAERE

by Tanaquil Sergius

Introduction

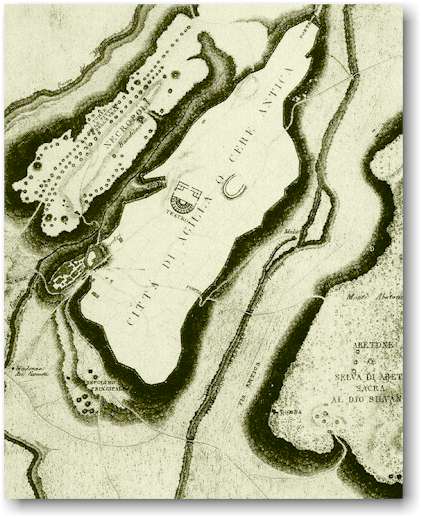

Caere, known to the Etruscans as Caisra, to the Greeks as Agylla

and to the Romans as Caere, metropolis of Southern Etruria, stands on a

rocky spur of Tufa, 80 metres above sea level, bordered by the rivers Mola and

Manganello. In later Italian periods, the place is known as Cerveteri or

"Ancient Caere". While little remains of the original Etruscan city,

the necropolis or "city of the dead" with the name of Banditaccia

(which was linked to the city of Caere by the monumental , so called, "Way

of Hades" boast world renown.

The city extends along a tufaceous plateau where the two rivers meet and it is not far from the sea. The presence of noticeable traces of protovillanovan settlements, particularly at Sasso di Fubara and Monte Abatone, testifies to the fact that this area was already densely populated in the prehistoric era. It is believed that the city was in the process of developing during the early Iron Age (9th century B.C.); this is borne out by the necropolis of Sorbo and of Cava della Pozzolana, which have given us numerous Villanovan burial sites, whose form is less developed than that of those found in other places in Southern Etruria, such as Tarquinii, Veii and Vulci.

The city's greatest period of prosperity, which is perhaps tied up with

the intense exploitation of the mineral resources of the Tolfa Mountains and

with the expansion of maritime trade, could already be clearly seen at the end

of the 8th century B.C. It was then that Caere became the centre in

which it is possible to recognize a whole series of crafts of great importance

such as the outstanding production of bucchero, a typical Etruscan type

of black pottery, of bronze and of Italo-geometric ceramics.

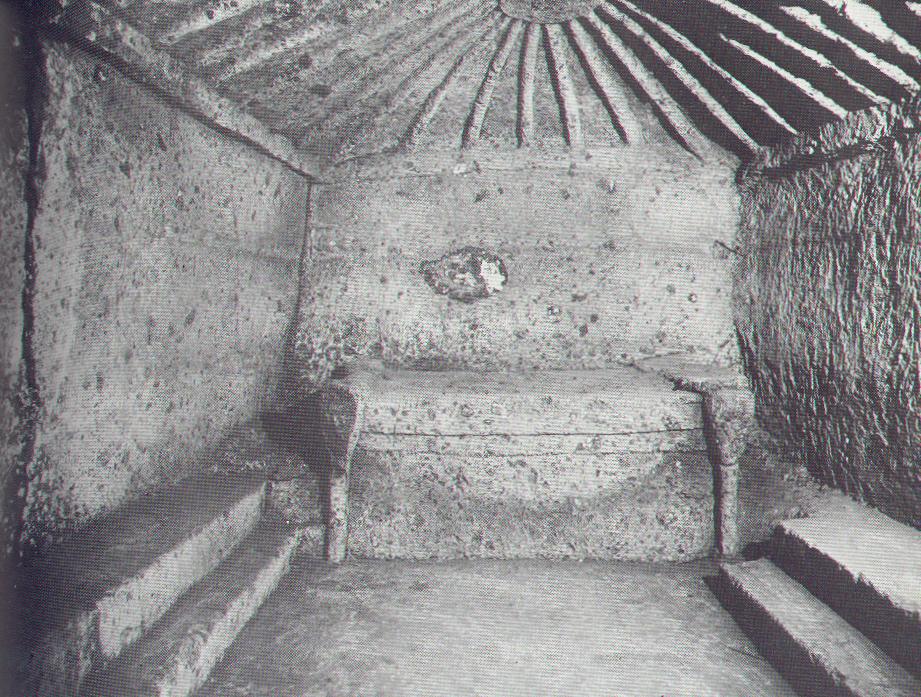

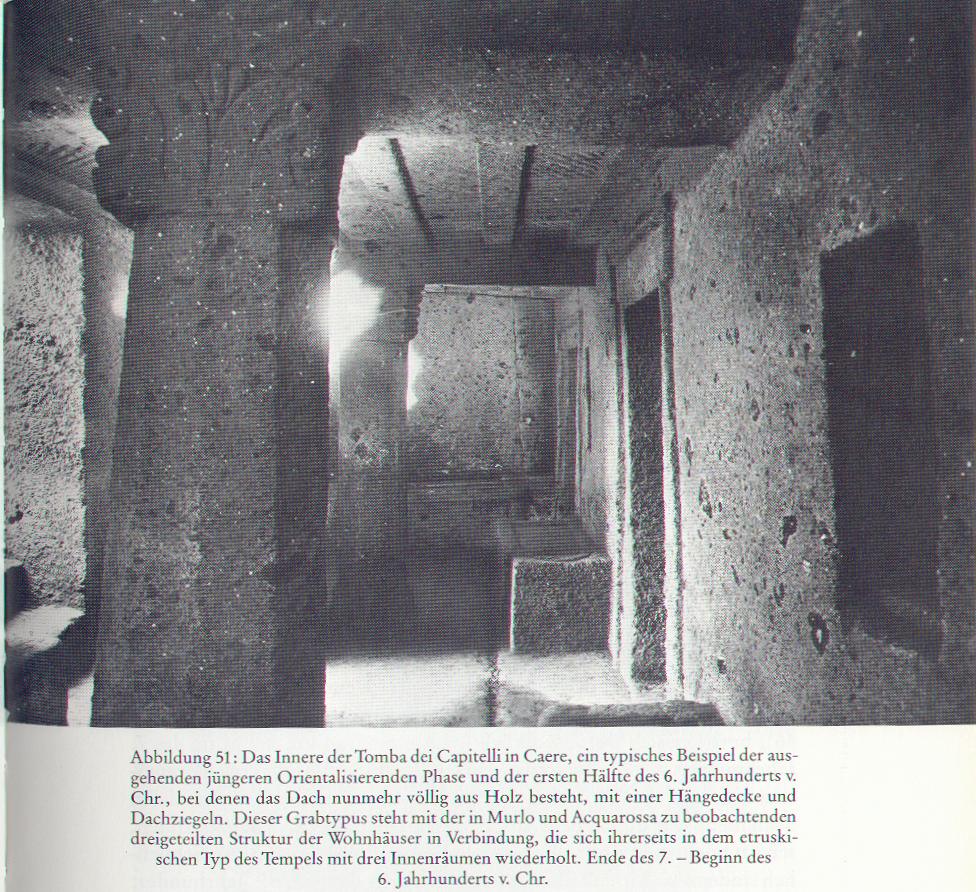

In the funeral rite, the Villanovan way of burying by cremation was soon replaced by inhumation and the first chamber tombs appear as early as the beginning of the 7th century B.C. These tombs imitate and therefore document the development of the architecture of city dwellings, which were in turn an expression of the rising Etruscan aristocracy, and it is from them, in the best cases, that outstanding grave goods have been brought to light.

The Tomba Regolini-Galassi, in the necropolis of Sorbo, is a

noteworthy example: an unusual combination made by the adding to and joining of

various surrounding burial places made it possible to discover intact, in 1863,

the oldest burial place composed of an entrance way, outer room and a cell. In

the central cell there was a buried corpse adorned with princely grave goods of

gold, silver, ivory, bronze and ceramics (now all in the Vatican Musea), which

can now be dated no later than 675 B.C.

The great glory of Caere continued in the 6th and 5th

centuries as well, when the city proved itself an important Mediterranean centre;

together with the Carthaginians, the city fought, with uncertain outcome,

against the Greeks of Phocaea in the Sardinian Sea, and Caere was the

only Etruscan city to have a "thesaurus" (i.e. treasure house) in the

sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi. The war notwithstanding there were nevertheless

strong cultural ties with the Greek world. This is documented not only by the

numerous examples of pottery imported from Hellas, but above all by the

influences on Etruscan art, as can especially be seen in the painted ceramics.

The workshop of the so called Caeretan Hydriai was set up at Caere,

probably by a craftsman or crafts family from Ionia. There are also influences

of Greek art in the clay modelling, as examples like the Sarcophagus of the

Married Couple , the Sarcophagus of the Lions and architectural

slabs in the British Museum clearly show.

In this period, funereal architecture too illustrated the high level of well-being reached in the city. The tumuli in the necropolis of Banditaccia and Monte Abatone are of grand proportions, such as for example the Tomb of the Greek Vases and the Tomb of the Shields and Chairs, and the attempt to give the cemetery areas a kind of urbanistic structure with straight streets and squares is worthy of note. Alongside the tumuli, from the middle of the 6th century on, also cube-shaped or dado tombs appear, which were socially connected to the upcoming middle classes and which have facades imitating the appearance of city dwellings, with a burial room underneath them.

The city

The ancient Etruscan town, and much of the Roman settlement, is loacted on a tufa plateau, about 150 hectares in size. Parallel to this, the city's famous necropolis, today called "Banditaccia" is situated. The ancient city is only partially covered by modern Cerveteri, yet only two spots of the area have been excavated. The urban area is shaped like a long triangle pointing north-east/south-west, bounded by the "Fosso della Mola" and the "Fosso del Manganello" streams, which, over the course of time, have cut out deep ravines into the soil.

In the urban area, two spots are under excavation: the first one, known as "Vigna Parrocchiale", is in the central part of the plateau, near the Roman theatre, in the very heart of the ancient city. The second one is on the southern boundary, near one of the town gates, in the so called San Antonio area.

The development of the excavations in Caere have made it possible to establish a unique and comprehensive model for the digital acquisition of excavation data, carried out in the central area of the urban plateau (see picture on top of this page) of the ancient Etruscan town. The information system as it has been designed has been applied to the Vigna Parrocchiale excavation area, close to the Roman theatre, where several archaeological phases have been identified, beginning in the Villanovan period (from about 1400 until about 900 B.C.E.) and continuing through until the Roman period. In this area, a cistern and some building remains have been found next to the structures of an elliptical building to its left. The open-air structure of the cistern, cut out of the tufa and characterised in the north-west corner by a canal, si of monumental proportions: it measures approximately 14 metres in length, 5 metres in width and 11 metres in depth: illegal digging was evident up to a depth of about 7 metres. This structure has been interpreted as a stone quarry of tufa blocks; it was then used as a cistern, until it was filled in at the beginning of the 5th century B.C.E., creating an artificial earth dump, in which different types of fine and coarse-ware pottery and architectural finds, relevant to the system of terracotta decoration of the aristocratic building alongside it, have also been found.

In the middle of the central urban area, excavations have also brought to light a necropolis dating from the 9th-8th century B.C.E. and an aristocratic building from the 6th century B.C.E., which was destroyed at the beginning of the 5th century B.C.E. and replaced by a temple and an open-air elliptical building.

A 19th century drawing of the excavations of the city of Caere and the Banditaccia Necropolis. To the right: the excavation picture of an elliptical building.

The Vigna Parrocchiale excavations: the elliptical building to the left and remains of buildings and a cisterna to the right.

Pyrgi, the port of Caere

"Pyrgi" was the principal port of Caere, identified in the area

of Santa Severa, where excavations, begun in 1957, have brought to light a

sanctuary, probably dedicated to the divinity Ilicia-Leucothea, and which

traditional sources say to have been destroyed in 348 B.C. by the tyrant of

Syracuse, Dionysios.

Historically, Pyrgi followed the vents of the metropolis of Caere, with a

period of great flourishing between the 7th and 5th

centuries B.C., corresponding to the Etruscan dominion of the seas.

From the 3rd century B.C., with the fall of Caere to the

Romans, a maritime colony was set up there, definitively established in the 2nd

century A.D.

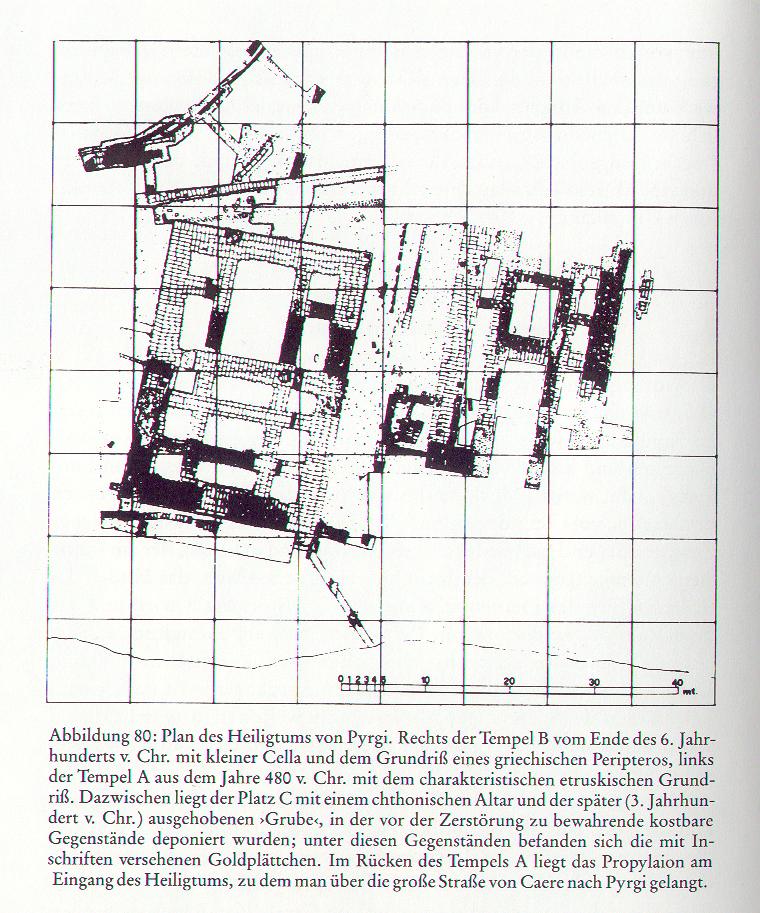

The sanctuary area consisted of two parallel temples, called

"A" and "B" by archaeologists, and a sacred area. Temple

"A" is made in the traditional Etruscan style with three chambers or cellae.

Among the remains of the clay decorations is a mythological frieze of

outstanding importance. This frieze, which decorated the back façade, contains

scenes of the myth of the Seven Against Thebes and it is now in the Museo

di Villa Giulia in Rome. The frieze is a work in the so called severe

style of the first decades of the 5th century B.C.

Temple "B",which is older than temple "A", is similar

to Greek structures with only one chamber surrounded by columns. It also has

clay decorations and friezes adorning the central beam work and the mutuli

of the façade, with scenes depicting the Feats of Heracles.

But the most sensational discovery from the Pyrgi excavations are

undoubtedly the three golden sheets with bilingual inscriptions in Phoenician

and Etruscan. These were found in a well between the two temples. Two of the

sheets are in Etruscan and one is in Phoenician as a translation. They refer to

the dedication, made by the king (Etr. lauchum) of Caere, Thefarie

Velianas', to the relations between Caere and the Carthaginians, who, as

sources tell us, had already fought against the Greeks of Phocaea at Alalia.

Archaeological plan of the temples A and B at Pyrgi.

Between the 5th and the 4th centuries B.C., Caere was hit by the general crisis of Southern Etruria, together with the decline of Etruscan naval power and the rapid strengthening of Rome. The abandonment of the city began in the Hellenistic Age and gained momentum during the Imperial Age. The abandonment of Caere was complete by the time of the High Middle Ages.

![]()

Sources:

The Caere

Site of Thanchvil Cilnei (Tanaquil Sergius)

The Caere Project

Literature:

Banti, L., The Etruscan Cities and their Culture, London, 1973

Boitani, F.(ed.), Die Städte der Etrusker, Basel/Wien, 1974

Canina, L., Descrizione di Caere antica, Roma, 1838

Cristofani, M., Città e Campagna nell' Etruria settentrionale, Arezzo, 1976

Dal Salvio, C., Popoli del Passato: Gli Etruschi, Milano, 1984, p. 18-29

Kolb, K., Die Stadt im Altertum, 1984

La Città etrusca e italica preromana, Atti del Convegno, Bologna, 1966, Bologna, 1970

Moretti, M., Cerveteri, Novara, 1977

Pfiffig, A.J., Die Ausbreitung des römischen Städtewesens in Etrurien, Firenze, 1966

Steingräber, S., Etrurien; Städte, Heiligtümer, Nekropolen, München, 1981

Explore! The

City of Caere