Researched and Written by John M. Gould.

Back to The Biography of John Mead Gould

Edward Sylvester Morse was born in Portland, Maine on June 18th, 1838. He was the son of Deacon Jonathan Morse, a staunch Calvinist Christian.Much to his father's chagrin, young Morse was expelled from every school he attended in his youth. These included the Portland village school, the academy at Conway in 1851 and the Bridgton Academy in 1854. Morse's curious young mind could not accept the confines of a classroom and he was easily distracted from his studies. Had he lived in our current age he most probably would have been diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.

Sometime prior to 1854 Morse made the acquaintence of his life long friend John Mead Gould. They attended Bridgton Academy together in summer of 1854 and explored the Maine woods together in their spare time. In the autumn Morse was expelled for carving on the desks despite the corporeal discipline of the schoolmaster.

Morse's brother then found him his first job as a draftsman at the Portland Company. The Portland Company made steam engines for trains and ships. While the subject of his drawings was far removed from his life's work in zoology it, nevertheless, developed his talent for making detailed drawings. This, coupled with his keen powers of observation, would enable him to pursue his career as a leading zoologist.

In June 1856 Morse attended Bethel Academy in Bethel, Maine. Here he was exposed to the influence of Dr. Nathaniel True. Dr. True recognized Morse's brilliance and was able to productively harness it by encouraging Morse's interst in collecting specimens from the natural world. True also allowed Morse to assist visiting biologists and mineralogists in their studies.

Due to ESM's disillusionment with the Cavinistic doctrines of his father, Morse began to pursue his interest in the study of nature. (In those days, particularly because of Darwin's anti-Biblical theory of evolution, science and religous faith were considered to be incompatiable with each other.)

On September 28th, 1856, while enrolled at Bethel Academy, he discovered a minute land snail. This discovery would launch him on his career as a natural scientist. In 1859 the Boston Society of Natural History would proclaim Morse's discovery Tympanis morsei. To be credited with the discovery of a new species and to have it named for himself was undoubtedly pleasing to the bright 20 year old.

Scientific Education

Professor Louis AgassizOn May 27th, 1859 Morse went to Cambridge, Massachusetts and met the eminent Louis Agassiz who held the chair of zoology and geology of the Lawrence Scientific School of Harvard University. Morse then studied marine biology under Agassiz's direction specializing in chonchology. As Agassiz was probably the foremost zoologist in America at that time, Morse could not have found a better mentor. In fact, the list of Agassiz's assistants and students during these years reads like a Who's Who of American natural scientists of the late 1800's.

This interest in pursueing his studies, as well as those of his fiance and recently widdowed mother, precluded his enlisting in the Union Army during the early stages of the Civil War. When he later tried to enlist on August 25th, 1862, in Company A of the 25th Maine Infantry Regiment, he was rejected on account of a chronic infection of his tonsils.

Throughout the war Morse corresponded regularly with his lifelong friend John Mead Gould and was the recipient of the letters which would form Gould's war journals.

On June 18th, 1863 Morse married Ellen ("Nellie") Elizabeth Owen in Portland with John Mead Gould as his best man. They had two children - Edith Owen Morse and John Gould Morse.

In 1866 Morse settled in Salem, Massachusetts where he would spend most of the rest of his life. Here he helped establish the American Naturalist magazine and became one of its editors. Early Career

In 1868 Morse built a house at 12 Linden Street in Salem. It would be his home for the rest of his life.

Over the next few years Morse would be associated with a number of pestigious organizations and institutions. In 1868 he was made a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1874 he was made a lecturer to Havard University. In 1876 he became a fellow of the National Academy of Science and in 1885 president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. He was also a member of numerous other organizations.

Morse undertook a study of brachiopods along the Atlantic seaboard which recieved international attention. In 1869 he was elected vice-president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and became its president in 1886. From 1871 to 1874 he held the chair of comparative anatomy and zoology at Bowdoin College.

Cover Illustration of How to Camp Out drawn by ESM.Around 1876 Morse prepared a few illustrations for John M. Gould's book How to Camp Out. In the introduction of the book Gould wrote - "Professor Edward S. Morse has increased the debt of gratitude I owe him, by taking his precious time to draw my illustrations, and prepare them for the engraver."

Experience in Japan

In 1877 Morse visited Japan in seach of new specimens for his studies and was offerd a position as a professor at Tokyo Imperial University and stayed until 1879. The book Mirror in the Shrine relates ESM's experiences in Meiji Japan along with those of two other Americans. Morse then began his collection of Japanese pottery, considered to be the finest of that era in the United States much of which would eventually be purchased in 1890 by the Boston Museum of Fine Arts where Morse was given the honorary title of "Keeper of the Japanese Pottery". Photographs of items from the collection may be seen HERE. Much of the remainder is now called The Morse Collection at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem.

In 1875 Morse published First Book of Zoology and in 1888 Japanese Homes and their Surroundings. As Morse was one of the few westerners to live in 19th Century Japan his writings are of great interest to historians.

In 1887 and 1888 Morse toured Europe. He landed in Liverpool on August 17th, 1887 and went on to visit England, France, Germany, Austria and Switzerland. He was to return to Germany in 1887 in order to fill out his Japanese pottery collection which was sold to the Boston Museum of Fine arts in 1890. Morse wrote a detailed catalog of the collection which is still a standard reference work in the field.

Order of the Rising Sun, 3rd ClassMorse's association with Japan would long be remembered on both sides of the ocean and in 1898 Morse was decorated with the Order of the Rising Sun, Third Class by the Emperor of Japan, making him the first American to be so honored. Near the end of his life in 1922 Morse was again honored by the Japanese Empire with the Order of the Sacred Treasure, Second Class.

Late Career

East India Marine Hall of the Peabody MuseumIn 1880 Morse returned to Salem. The next year he took up his life's work as director of the prestigous Peabody Academy of Sciences (known today as the Peabody Essex Museum). During his tenure the museum developed its world renowned collection of Oriental art in addition to its nautical holdings. In this capacity, Morse acquired such renown that he was elected president of the American Association of Museums in 1911.

In 1882 Morse gave a lecture series at the Lowell Institute on Japanese culture.

Percival Lowell

Among Morse's many friends in the scientific community was astronomer Percival Lowell. Lowell is probably best known for his observations of Mars and his hypothesis that the lines seen on the red planet through a telescope were canals built by the planet's inhabitants. His observations were published in a book called MARS in 1895. Morse would occaisonally travel to the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona during prime times for observation of the planet.Lowell's indirect contributions to the founding of the modern "science" of UFOlogy cannot be underestimated. Lowell's hypothesis about Martians most probably inspired H.G. Wells to write The War of the Worlds in 1898 which, of course, led to Orson Welles' famous (or infamous) Halloween hoax in 1938. Since then there has been strong speculation that humanity is not alone in the universe and that we may have been visited by inhabitants of other worlds.

In 1906 Morse published Mars and its Mystery as a defense of his Lowell's theories. It was the only work of Morse's about a subject where he was not a leading authority. Even so, it was good enough to get Morse elected to the French Astronomical Society.

Final Years

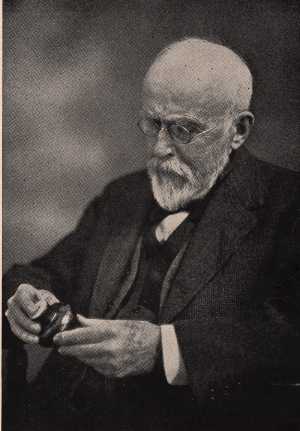

ESM Examining a Piece of Japanese PotteryIn 1911 Morse's wife Nellie died. He was cared for in his later years by the Brooks sisters - Josephine serving as housekeeper and Margarette as his ever faithful administrative assistant.

On June 25th, 1914 Salem was engulfed by a great fire which consumed most of the city. By good fortune, the flames were stopped within four blocks of Morse's house. Two of his scientific colleagues rushed over to assist him in saving the important scientific materials Morse kept at his house.

Instead of finding Morse consumed with panic at the potential loss of his life's work, they found him sitting in his study attempting to play a South Sea Island flute with his nose. Morse's words on his friends' arrival were, "The Solomon Islanders can do it; why can't I?"

On June 18th, 1925 Morse recieved a scarlet cap from Dr. Chiomatsu Isahikawa who was a pupil of Morse's in 1877 and succeed to Morse's chair of zoology at the Imperial University. Japanese men of distinction are given scarlet cap on their 88th birthday as a symbol of their long life and achievements. While the cap was, indeed, an honor it also indicated that Morse's life was drawing to a close.

Edward Sylvester Morse died in Salem on December 20th, 1925 at the age of 87. Upon hearing of his best friend's death John Mead Gould wrote in his diary, "What is the world and life here if no Ed Morse?".

Morse's funeral was held at the First Unitarian Church in Salem. He was buried in the Harmony Grove Cemetery in Salem.

Morse's contributions to the advancement of scientific knowledge extended beyond his death. His will dictated that his brain be donated to the Wistar Institute of Anatomy and Biology in Philadelphia to be studied to attempt to determine the causes of ambidexterity. Epilogue

In 1930 Commander K. Mizuno of the Japanese Navy, one of Morse's students at the Imperial University, made a pilgrimage to visit Morse's brain. Mizuno wrote - "Here I am, Professor," said I in my heart, "to see your brain as you requested." A voice seemed to reply, "Good, my boy, but I am in Hell. Are you brave enough to come down here?" (Wayman, pg. 435.)

In 1942 the only full length biography of ESM was published. It was named, appropriately, Edward Sylvester Morse and was written by Dorothy G. Wayman and published by Harvard University Press. This work was the primary source for much of the above information. He was also the subject biographical articles in the Dictionary of American Biogaphy and Appleton's Cyclopedia of American Biography.

Related Links

Amazon.com listings of titles relating to ESM.

Another On-Line Biography of Edward Sylvester Morse.

Use YAHOO!! to search the Net.

Send E-Mail to jmgould39@yahoo.com