|

Last Page Update:

May 14, 2001

Contact

Copyright Information

Main Page

Structure of the Red Kaganate

Gatherings, Events, . . .

Historic Steppes Tribes

Legends of the Nomads

Flags and other Identifiers

Clothing and Apearance

Food and related Matters

Armour

Archery

Weapons and Combat

Public Forum

Resource Links

Email:

kaganate@yahoo.com

Editor:

Norman J. Finkelshteyn

|

Fighting with the Saber

Comments by Norman J. Finkelshteyn

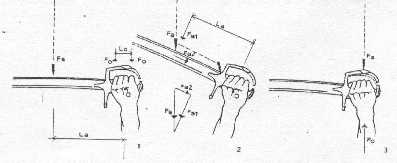

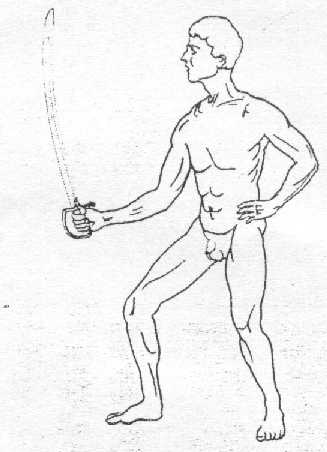

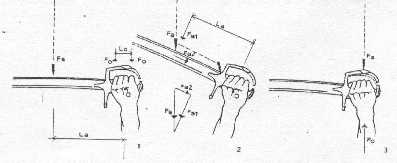

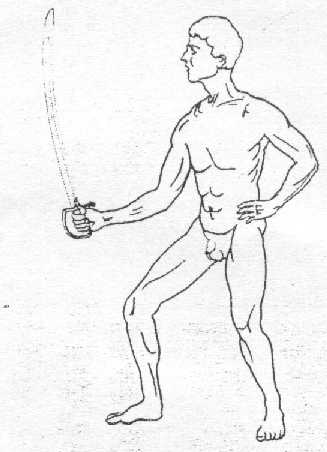

Images from Michal Starzewski's "Treatise on Fencing" as presented by Richard Orli

|

DISCLAIMER: This is a brief overview that assumes a set of skills on the part of the reader. The Saber is an inherently dangerous instrument. The practice of fencing requires discipline, training, and protective equipment. This page is presented solely for the academic interest of the subject matter.

|

The images here are taken from the Web Site "Boleslav Orlicki’s Horse Artillery XVIIth century", from the electronic article by Richard Orli - 'Highlights of Wojciech Zablocki's review

"ANALYSIS OF FENCING MOVEMENTS" (Analiza Dzialan Szermierczych) in Ciecia Prawdziwa Szabla (Wydawnictwo "Sport i Turystyka" Warsaw, Poland, 1989)' - http://www.kismeta.com/diGrasse/Zablocki.htm.

The images themselves come from an 1830 Polish manual - "Treatise on Fencing" by Michal Starzewski.

The article has a substantial amount on the use of the Saber by the Poles, as well as brief comparisons of the several types of Polish Saber and the Sabers of other cultural groups. The Site as a whole http://www.kismeta.com/diGrasse/PolishHorseArtillery.htm offers extensive, reenactor focused information on Polish military culture in the 17th century.

|

Targeting the Cuts

Prior to seeing Mr. Orli's review, I have never found manuals specific to the Saber when the Saber was a substantial cavalry weapon as opposed to the modern fencing Saber. I was impressed, as I think anyone who has fenced with a sports Saber will be, at how similar the techniques are.

At the same time, the differences should be noted. While as war swords go, the Saber is considered a light weapon, it is nevertheless substantially heavier then the sports Saber. Both the grip on the weapon, as well as the techniques must reflect this. It will, for example, be noted that the pivot points for the weapon are the wrist and elbow, rather than the fingers counceled in sports Saber fencing. Similarly, the rotation of the weapon on a movement, whether attack or defense, is overall substantially increased.

Holding the Saber

While this manual comes from the 19th century, as the Saber itself has changed only slightly between the 8th century and the 19th, I feel quite comfortible making an assumption that earlier technique was quite similar. Until a better aproximation can be found, these techniques can, I believe, be confidently used as aproximations of Saber use in earlier periods.

Major differences to be nevertheless considered mainly focus on the grip of the weapon. While late Polish Sabers quite commonly had a knuckle guard, and sometimes substantially more hand defense than that, and some even had a support ring for the thumb (see Mr. Orli's article), as far as I have been able to ascertain, Sabers prior to the 16th century uniformly had only the most minor of cross guards.

|

Basic Guard Positions

|

|

|

|

High/Hanging Guard - See Parry Two

|

Low Guard - See Parry Three

|

A note on the Parries -

At a glance, it seems that the illustrated parries have the blades meet cutting edge to cutting edge. This is also a natural style to adopt for a person coming from sports Saber.

The current concensus, however, is that this is not proper technique. Edge to edge contact would cause substantial damage to blades, quickly turning most swords into ugly saw-blades with cuts and chips. It is far more likely that an edge was parried with the side of the blade or the parrying blade edge was imposed towards the side of the attacking blade.

This is easily achieved with a slight shift of wrist position and, after a little practice, becomes as natural as the opposite technique.

Basic Parries

|

|

Parry One

|

Parry Two

|

Parry Three

|

|

Parry Four

|

Parry FIve

|

|

|

Parry Six

|

Move from Hanging Guard / Parry Two

into Parry Five

|

|

Basic Attacks

|

Head Cut

|

Belly Cut

|

Thrust -

Thrust -

Sabers from different periods and locations often differ with respect to angle of sword point, curve of the blade, and presence or absense of a "false-edge" (a part of the back of the blade, from point to sometimes 1/3 of the length of the blade, which is sharpened).

These differences can influence the effectiveness of a thrust and the likelyhood that such technique was used with the particular Saber.

The Sabre, used from horseback on the charge, is properly a thrusting weapon before it is a cutting weapon. It is properly a cutting weapon only when the battle degenerates into a circling melee. This even applies to very curved sabres!

Put yourself into a in-saddle-like position, lean forward, stretch out your

arm, and you will see that using the point as a spear works well with the

curve, and with the curve, it is less likely that the sabre will be torn

from your hand on the hit (imagine hitting a target galloping toward you,

when you are galloping toward it!), but will arc back and up out of the

wound as you ride through... much is made of the benefits of the curve for

the cut, but this behaviour is an important feature of the overall design.

As I observe, on foot, thrusts are less important, but still important.

Richard Orli

|

Cut from the Shoulder -

Cut from the Shoulder -

The further the fulcrum of the cut away from the point of the sword, the larger the necessary motion to execute a technique. Thus, with a Sports Saber, a move of the fingers can shift the blade from one point of attack to another or from defense to attack and vice versa. Slightly more movement is necessary for motions from the wrist and even more when cutting from the elbow.

With a cut like the one presented here, the attacker is quite fully dedicated to the cut from begining to end and will find it hard to change the attack or to reposition for a parry.

On the other hand, the potential for power is the most substantial.

Some of the moves, like big cuts from the shoulder, make more sense

when you think of it as a from-horseback style maneuver.

Richard Orli

|

Moulane -

Moulane -

This cut is done from Parry One or the one labeled Six in this manual (note: modern fencers will likely be familiar with a very different "Six").

The cut will either be to the head or to the upper part of the analogous side of the opponent's body (ie: if the left of the body was defended, the counter will be to the opponent's left). The wrist flips the sword fully about, building momentum due to the mass of the blade.

The move is fairly meaningless with a sports Saber and likely innefective. With a full sized Saber it is quite important -- the momemntum of the heavier blade makes this cut actually faster and more powerful than one that does not utilise the arcing motion.

|

Combinations

|

Beat Cut - Feint to Head, then repeat Cut to Head

|

Feint Head, Cut Belly

|

Counter Attacks into an Attack -- Cuts to the Arm

Evading with a Counter Attack

In addition to the above-sited works, Mr. Orli also provides an extensively commented Web version of the Fencing manual by Giacomo Di Grasse - a very important 16th century Italian work - http://www.kismeta.com/diGrasse

|

Thrust -

Thrust - Cut from the Shoulder -

Cut from the Shoulder - Moulane -

Moulane -