MEHNDI Indian henna bodyart

|

![]()

Mehndi (pronounced meh-hend-dee) - HENNA in English (or maruthani in Tamil/S India; saumer Sudanese name for black henna used on the soles of the feet and popular with men - also obtained by mixing with indigo dye; or reseda) - is best known in the West as a reddish-brown hair dye with conditioning properties that make it a popular ingredient in hair-care products. In the East, however, it has also traditionally been used as a skin colourant and is central to the long traditions of temporary tattooing (tattoo is a Polynesian word).

Mehndi is the dried and powdered leaf of the dwarf shrub LAWSONIA INERMIS, a member of the Loosestrife family, Lythraceae, which grows to a height of about 2½-3m. A distilled water preparation used for cosmetic purposes is made from its small, sweet-smelling, pink, white and yellow flowers. It grows in hot climates and is supplied mainly from Arabia, Iran, Ceylon, India, Egypt, Pakistan and Sudan, though it may also come from China, Indonesia or the West Indies.

The green powder of the dried leaf is mixed with tea, coffee, sugar, lemon juice, eucalyptus and clove oils, and sometimes tamarind paste to a thick paste. Cones are more used today rather than sticks, and the are made out of polythene bags and used as one ices a cake. The skin is usually cleaned with rose or orange flower water then prepared with oil such as eucalyptus - sometimes a transfer is applied first.

The mehndi should be left on for at least 2 hours and preferably up to 8, to ensure the darkest colour possible. It can be kept damp with a mixture of sugar and lemon juice and crumbled off when ready. The pattern on the skin will be an orange-red colour but will darken to brown, and last several weeks depending on how often it is exposed to water. Moisturiser will help to retain it longer.

The history of mehndi goes back 5000 years. It is said to have been used in ancient Egypt to colour the nails and hair of mummies. In the 12th century, the Mughals (Moguls) introduced it into India, where it was most popular with the Rajputs ot Mewar (Udaipur) in Rajasthan, who mixed it with aromatic oils and applied it to the hands and feet to beautify them. From then on mehndi has been regarded as essential to auspicious occasions, particularly weddings.

It was only after reaching India that mehndi gained real cultural importance, its use by the rich and royal making it popular with the people. Servants who had learnt the art of mehndi by painting the hands and feet of princes and princesses (with fine gold and silver sticks) were very much sought after in towns and villages for their skills. As the use of mehndi spread, recipes, application methods and designs grew in sophistication.

In Persian art - most notably in a famous series of miniatures dating from between the 13th and 15th centuries - women taking part in wedding processions and dancers are depicted with mehndi decoration on their hands. It has been suggested that in the scorching heat of Arabia, mehndi was often used on the skin for its coolant properties.

Hindu goddesses are often represented with mehndi tattoos on their hands and feet, and Muslims have used mehndi since the early days of Islam. It is said that the prophet Muhammed used it to colour his hair as well as, more traditionally, his beard. He also liked his wives to colour their nails with it. That Muhammed was and remains a model of perfection for Muslims has ensured the continuing popularity of mehndi as a decorative art within Islam.

Mehndi across Cultures

With the passing of centuries, mehndi has gained in significance in cultures within the middle East, Asia and North Africa. All of these communities use mehndi for the same purpose: to decorate and beautify; however, each one has its own unique designs, inspired by indigenous fabrics, the local architecture and natural environment, and individual cultural experiences.

In south India, a circular pattern is drawn and filled in in the centre of the palm. Then a cap is formed on the fingers, as if they had been dipped in mehndi. This design is used by most Asian elders, as in the early days before cones (similar to icing bags) were available it was simple to apply. It is this design that is used by south Indian classical dancers.

In north Africa, very intricate designs are developed around peacock, butterfly and fish images, which are completed with finely detailed patterns. The effect is that of a lace glove, as great attention is given to filling in the gaps that surround the main motif. Religious symbols are incorporated, such as the DOLI, a form of hand-pulled carriage which was used to transport the bride from her home to her in-laws’ house in the days before cars. The lotus is also popular.

Many people confuse Pakistani with north Indian designs, because both are intricately applied to give a lacy glove-like effect. In fact, however, Pakistani designs are a blend of the north Indian style and Arabic motifs - flowers, leaves and geometrical shapes. This choice of motif derives from religious teachings: Muslims must not pray with figurative representations on the body, and so do not employ designs depicting human faces, birds or animals.

Arabic patterns are well spaced on the hand, and traditionally completed by dyeing the nails with mehndi to give a deep stain.

Sudanese patterns are large bold and floral, with geometric angles and shapes, normally created with black Henna.

Mehndi Wedding Customs

Mehndi has great significance in all Eastern wedding traditions, and no wedding is complete without the decoration of the bride’s hands and feet - in many cultures on both the front and back of the hands right up to the elbow, and on the bottom half of the legs. The mehndi night is something like a hen night in the West, with all the bride’s female friends and relatives getting together to celebrate. They spend the evening singing traditional mehndi songs, which tell of he good luck and blessings that mehndi will bring, and of its significance with different in-laws.

"Oh, how sleep is hard to come by, once her hands have been adorned with the mehndi of her beloved."

"Oh, friends, come and decorate my hands with mehndi, write my beloved’s name. Just see how auspicious this occasion is."

"Everyone’s fate is held within the lines on our palms, it is on these palms that mehndi paints such beautiful pictures."

The mehndi night is common in the Gulf regions of Saudi, Bahrain, Kuwait and the UAE. Here, the celebration is generally held a few days prior to the wedding, and is strikingly similar to that of Indian culture. The bride has her hands and feet painted, and traditional songs are sung by the mothers and grandmothers, who tease her about her future. Mehndi also features in other Middle Eastern celebrations such as births and christenings.

In Gujerat, mehndi tattooing is part of the Adivasi women’s wedding traditions. Leaves and flowers are used as templates around which complex designs are painted on the bride’s face and arms.

The mehndi ceremony is considered so sacred in some religions that unless the mother-in-law has applied the first dot of mehndi to the bride’s hand, the painting cannot go ahead. The mehndi dot is considered to be a symbolic blessing, bestowal of which permits the new daughter-in-law to beautify herself for the groom.

Many brides believe that the deeper the colour of the mehndi, the deeper the love they will receive from their in-laws, in particular the mother-in-law, whose blessing is particularly important to an Asian bride. Hence she does whatever she can to ensure that the mehndi stain is deep.

Traditionally, the groom’s name is incorporated into the bride’s mehndi tattoos, and it is task to find it - which may take up to two hours. In some customs the bridegroom’s hands are also decorated, and communities in Kasmir and Bangladesh have evolved particular men’s designs. A current trend in the UK is for traditional patterns in the form of a ring or bracelet.

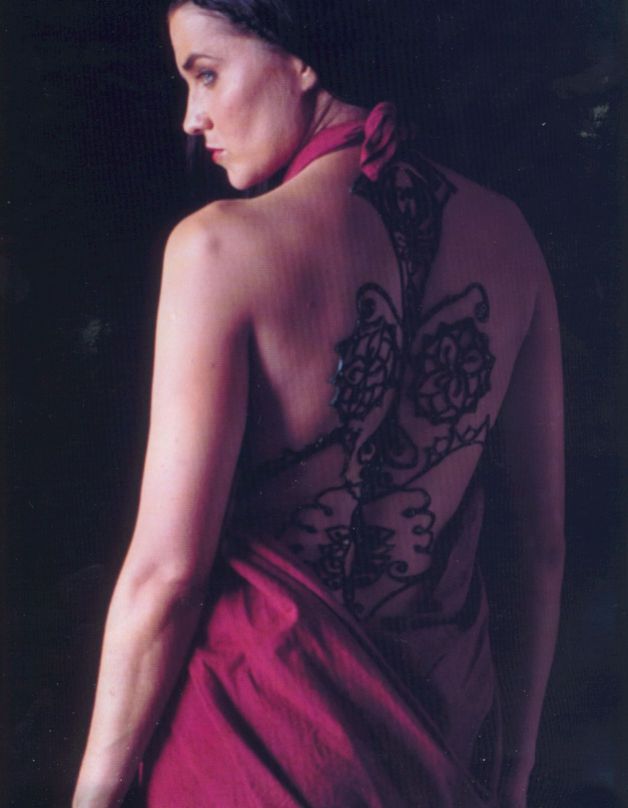

The recent interest in bodyart has popularised Celtic designs on, for example, armbands and the back, and floral designs around the navel, as well as Maori style facial art.

Other Properties and Uses

Mehndi has been used to treat a number of ailments due to a brown substance of a resinoid fracture found in it. This has chemical properties which characterise tannins, and is therefore named hennotannic acid. It has been used both internally and locally to treat conditions including leprosy, smallpox, cancer of the colon, headaches and blood loss - especially during childbirth. It can be used for skin conditions such as eczema. The plant can also treat muscle contraction and fungal and bacterial infections.

Mehndi flowers produce perfume, and the Egyptians are believed to have made an oil and an ointment from them for increasing the suppleness of the limbs. The fruit is thought to have emmenagogue properties.

'When she puts henna on her hands and dives

in the river

One would think one saw fire twisting and

Running in the water.'

----------- Dilsoz, 18th century AD

Unlike real tattoo, which is permanent, some decorative patterns created on the skin with stain or dye are not immediately removable but, depending on the dye strength, can last for three or four weeks. Mehndi, the Hindi term for "henna," is one such temporary tattoo.

Men agree that mehndi patterns on a woman evoke thrilling, erotic sensations, perhaps because they associate mehndi with a maiden's initiation into mature womanhood.

The custom of applying elaborate mehndi patterns to the hands and feet is a symbol of satisfaction and happiness in marriage among the Hindus. This belief derives partly from the dye's red color, universally considered to be auspicious; and which is also the color of a bride's dress. Mehndi is commonly applied to propitiate Ganesha, the elephant-headed god, son of Shiva, who overcomes obstacles and is always invoked to attend a Hindu marriage ceremony. It is also considered very dear to Lakshmi, goddess of wealth and fortune. Indeed if ever there was a plant associated with luck and prosperity, it is the henna bush.

Mehndi has a great significance in all Eastern wedding traditions, and no wedding is complete without the decoration of the bride's hands and feet - in many cultures on both the front and back of the hands right up to the elbow, and on the bottom half of the legs.

Mehndi is carried out on a bride's hands and feet the night before the marriage celebrations begin, often known as the 'mehndi ki raat' or night of henna, raat meaning night. A party of the bride's women relatives spend several hours at this joyful task, during which they sing appropriate songs, teasing her about her future:

Oh, how sleep is hard to come by, once her hands have been

adorned with the

mehndi of her beloved."

"Oh, friends, come and decorate my hands with mehndi, write my

beloved's

name. Just see how auspicious this occasion is."

"Everyone's fate is held within the lines on our palms, it is on

these palms

that mehndi paints such beautiful pictures."

The mehndi night is something like a hen night in the West, with all the bride's female friends and relatives getting together to celebrate.

For the bride, the process is therapeutic in calming and preparing her for the event.

Mehndi signifies the strength of love in a marriage. The darker the mehndi, the stronger the love. The color of henna specifically has symbolic significance because red is the color of power and fertility. Many brides believe that the deeper the color of the mehndi, the more passionate the marriage. The design itself is important, too. Sometimes the groom's name is incorporated into the bride's complex mehndi tattoos, and it is a delightful task to try finding it - often taking up hours to accomplish.

After marriage, mehndi may be applied to a woman on any auspicious occasion, such as the birth or naming of a child.

Mehndi designs are an aspect of folk art requiring a well-developed decorative sense. Though the community perpetuates old patterns, innovative designs may also be introduced, which gradually enter the communal design repertoire. But an interesting aspect is that whatever be the innovation or tradition, only vegetative motifs are used. Thus henna is an attempt to symbolically link women with the vegetative and organic nature of Nature, along with its associated concepts of birth, nourishment, growth, regeneration etc.

Additionally, the purpose of tattooing is mainly apotropaic: to it is credited an evil-averting, magical function. Especially in animist societies, the tattoo acts to repel the forces of evil believed to be constantly active and attempting to gain advantage over the unwary, unprotected individual, causing misfortune, illness, or even death. In India, it is believed that an auspicious occasion like a marriage requires an extra protection against evil forces. This is because such occasions are celebrated with much pomp and show, amidst a high profile, making the probability of their being noticed by negative forces very high. The application of henna is thus an attempted safeguard against any such dark influences.

As well as being a lavishly colorful cosmetic, Mehndi is also supposed to have many healing qualities, many herbal doctors still recommend the use of Mehndi for some ailments, such as dry skin and to hasten the healing of cuts and scratches. It also acts a hair conditioner when applied on the head and is also said to stop hair loss by strengthening the roots of the hair.

According to Loretta Roome, a henna expert, in societies where mehndi is traditionally practiced, marriages are often scheduled to coincide with ovulation. "That's part of the intention," she said. "It's a fertility rite. The henna is the color of blood, representing the breaking of the hymen. In fact, Muslims call mehndi 'love juice."'

http://www.exoticindia.com/

![]()