Our stories are inextricably interwoven.

What you do is part of my story; what I do

is part of yours. Daniel Taylor

There isn't a memory of my early childhood that isn't in some way intricately and inseparably interlaced with the life of our family drugstore and the lives of my uncles who worked there. And the pharmacy did live in our minds. It had a decided life of its own, and it affected us all. My father's life centered around the store, of course, because it was the way he earned his livelihood; but it meant much more than that, even to him: the store gave our family a purpose -- a raison d'être -- that I have not seen many other families possess, white or black. But of all the second-generation children who were exposed to the business, I think it affected me most, simply because I spent so much of my childhood there.

As I grew into adulthood and began to accept more responsibility around the store, I found myself being treated more as a younger brother, than a son or nephew. This feeling strengthened the bond between my uncles, my father and me. We shared so much in common, since they, too, had grown up in and around the store, and could not remember when the business didn't play a seminal role in their lives. But now they are all gone. Of the four Johnson men who ran the pharmacy, only I remain, and so it falls upon me to record what it was like growing up with (and in) Dr. C. C. Johnson's Pharmacy.

I was born on the 30th of January, 1941, in the Johnson family home on the corner of Richland Avenue and Kershaw Street in Aiken, South Carolina. Almost from the moment of birth, although I had no way of knowing it at so tender an age, the store had already begun to affect me, for shortly after my birth, my mother began to work there. She would take me with her as an infant and place me in a cardboard Kotex© shipping carton upon a blanket padded with excelsior in the rear of the store while she worked. Later, when I was able to walk, I was left at home with my grandmother, Cecelia, who would look after me during the day. What I consider my earliest memory of my mother working is perhaps not so much a memory as it may be a tale I've heard my mother tell so often it is nearly impossible for me to decide if I really remember it at all. It centers around a morning in the early 1940s as she was leaving for work. I cried because I was being left at home, but when my mother turned back to see about me, I reportedly dried my tears and said, rather nonchalantly, "Oh, that's all right. Go on," as I turned away to involve myself in play. That says a lot about how spoiled I was, but it also hints at how close I felt to Mama Cele, my grandmother -- so close, in fact, that in the absence of my mother I did very well. But the drugstore was to have an even more concrete effect on my life.

The older I grew, the more time I spent in the store. In lower elementary school, my contact was limited to visits, but as I moved on in school, I was expected to do odd jobs around the store, for which I received a weekly compensation. What it amounted to was an allowance, but an earned one, and it came from my father's pocket in those early days. My jobs then consisted primarily of emptying the trash and sweeping the floors at night. My Uncle Lat (Ladeveze) and I would accomplish this latter activity on a nightly basis, and I remember vividly how we sprinkled Dust-Down compound on the floor prior to sweeping. And after sweeping, we would generally mop the entire store. As memories of those times spent with my uncle come flooding back, I feel the need to digress and write a little about him, since he was such a special person to me. I don't want him to become just another of my relatives without a discernible face, and about whom almost nothing is known.

Ladeveze Wilson Johnson was born May 9, 1910, the fourth child of Dr. Charles C. Johnson and Cecelia Elizabeth Ladeveze, in the same house as his brothers and sisters, the same house in which I would be born 31 years later. My grandmother told me that as a boy he loved to mimic the preacher at Sunday service in play. He'd use a white hankerchief for effect, wiping his brow as he imitated the preacher's excited rantings during the sermon. She also described him as being a sickly, rather delicate child growing up.

Uncle Lat, I called him, was a handsome man, and to my view the better looking of the boys in his family. He attended local elementary and high schools, then briefly attended Paine College in Augusta, Georgia before graduating from South Carolina State College with a bachelor's degree.

The earliest memory I have of him must have occurred very close to 1945, toward the end of the Second World War, when he returned home on furlough. I remember there was much "to do" surrounding that visit, and I also remember looking up at this strange, tall (to me at the time) man in his Army khaki uniform, and being told this was my Uncle Lat. When he left for the Army shortly after the war began, I was much too young to know who he was, but as he later settled in after the war, he and I became closer in some respects than he and his brothers were. By way of showing that there was a special bond between us, even when I was only a child, I will relate here something that happened soon after he came home.

While he was in Africa, my uncle contracted malaria, and not long after his return home, he had a malarial attack that put him in bed. He was living in the "home house" on Richland Avenue, Aiken, at the time, and had moved back into his old room -- the room I had occupied while he was away. I was only a boy, perhaps no more than 7 or 8 and living there too, but I well remember him wrestling with the disease and its horrible sweats. Even as sick as he was, though, he was determined that he wouldn't be taken to the hospital. He called for me that day, and in his most solemn of faces made me promise I wouldn't let "them" take him to the hospital. Imagine that...me, a mere boy! What did he think I could do? He had a morbid dread of going to the hospital for some reason. He was delirious, of course, I now realize, but at the time it made me feel so ashamed and guilty when the ambulance arrived in due course and carted him off to Augusta to the VA Hospital. I was devastated to think that I had made a promise to him, in many respects my favorite uncle, that I was unable to keep.

But as time went by and he recovered from his malarial attacts, life for him began to assume some sort of normalcy. On many nights, as I rode with him on the final prescription deliveries of the day, he would talk to me about events and concerns that bothered him that he wouldn't mention to anyone else. In this sense, he treated me like the son he never had. I felt honored that he would speak so frankly to me at such a young age about matters, often personal, and I never mentioned anything he told me if I felt it was something he wanted kept in strict confidence.

Another incident comes to mind as I remember how protective Uncle Lat often was of me. In the early 1950s, when a military jet crashed in a field outside of Aiken, he and I went out to see the wreckage. It was some time later that I discovered he had deliberately stood between the wreckage and me while the body of the pilot was being removed so I wouldn't see the burned and mutilated corpse. That was an example of how sensitive a person he was.

Uncle Lat stood about 5 feet, 6 inches tall, had straight to slightly wavy brown, almost black hair, brown eyes and a fair complexion. I suspect he took his features from the Ladeveze side of the family. He weighed about 160 pounds, with a rather slender build, and his weight never fluctuated. He ate what we wanted and never gained a pound. My favorite memory of him finds him standing, reared back, half a cigar clamped in his teeth, his thin lips pulled up at the corners into a smile of contentment.

Since the Army in some ways had a profound effect on my uncle's life, I should write about what little I know about his military service, and I should begin by stating that he was the only one of the three brothers at the store who saw any service during WWII. He was drafted, and for a long time after he had returned from the war, his "Greetings" letter remained in a desk drawer near the large safe in the back of the store. I remember talking to him about it, and about how he felt when he was drafted. I remember he was bitter about it; he felt singled out since he was the only one of the three who had to go. In all deference to his opinion, it must be stated that he was the only one who had no legitimate grounds for deferment. He had no critical occupation or wife and children to offer him an out.

Uncle Lat served with the Third Army under General George S. Patton's command in North Africa, driving supply trucks in the Quartermaster Corps. The Army was still segregated at that time, so he served with an all black unit. To my knowledge, he had never taken a life, but he was involved in some scary situtations while transporting supplies to the front lines. As for rank, he never rose above corporal, but that was by design. He once told me he was offered promotion to sergeant but turned it down because he didn't want the added responsibility. It was clear to me, and I suspect to anyone else who knew him, that he was never interested in making the Army a career; like so many millions who were drafted during that war, he simply wanted to serve his time, get it over with and come home.

Once the war was over, he returned to work at the drugstore and began to pick up the pieces of his life. How much his personality was affected by his war experiences, I am not in a position to say, as I only came to know him after the war. I imagine, though, from the stories he told me and from our conversations, that his living through World War II changed him considerably.

But Uncle Lat, just as all of us who worked there, had certain responsibilities at the store. He occasionally refilled prescriptions, especially during lunch break, when my father and Uncle Charles were out, but that was something he never liked to do. Most often, he could be found waiting on customers and restocking shelves. He was also responsible for nightly cleanup, going to the bank, and making home deliveries during the day. He, my father, and my Uncle Charles usually took turns making home deliveries after closing.

After my father gave up trying to make a go of the photographic portrait studio he ran for a time in the 1950s, Uncle Lat took it over, but he, too, was unable to turn it into a profitable business, so he eventually gave up on it as well. But Uncle Lat had the studio at the time I first became interested in photography as a hobby as a boy, and it was he who gave me my first instruction in developing film and printing photographs. The studio was rented out after he gave up photography, and converted into a tailor shop, operated first by Mr. A. D. Smith, then later by Mr. George Weaver.

The only vice I ever knew my uncle to have was cigars. Uncle Lat loved cigars -- and an occasional pipe -- but he would seldom actually smoke his stogies. More often than not, he would gnaw on the same cigar most of the day while he fussed and complained. I do not think it besmirches his memory at this point, some 33 years after his death, to tell the truth as I saw it: he was a chronic complainer. That was possibly the most striking difference between he and his brothers, but for me the jury is still out as to how much of that complaining was justifiable -- especially in his final years -- because of his physical condition. Regardless, his often sour attitude and depression kept a dismal cloud over his head. Even so, that fact does not diminish the deep respect I had for him, or the love, and I mention it only because it was his way, and because it goes a long way toward explaining his personality to someone who may never have known him. I firmly believe that he complained so often and so much that the family in general had a tendency to overlook his ususally dour attitude and chalk it up to his being "just Lat." What none of us suspected during those years we endured his complaints was that there really was something physically wrong with him. When his symptoms became progressively worse to the point where he was forced to seek medical attention and he began to actually look physically ill, all of us were understandably surprised and alarmed.

For the longest time, none of his doctors seemed to know exactly what was wrong with him, even though he had undergone test after test at the VA Hospital in Augusta. Eventually the diagnosis of multiple myeloma emerged, but this information was initially witheld from him. We (the family, that is) all knew immediately after the diagnosis was made, but were instructed not to tell him, I imagine because no one knew quite how he would react. Well, in due time, he found out anyway, quite by accident. When he heard his diagnosis, he was crestfallen. I remember him commenting to me later, as he literally wrung his hands with the pain of his shingles, "And to think! My own brother...my own brother wouldn't tell me!" He was referring, of course, to his brother Reed Poindexter Johnson, the physician. As it happened, he accepted his fate far better than anyone had imagined, and as we shall see later, he was able to accomplish some planning for his family before his death.

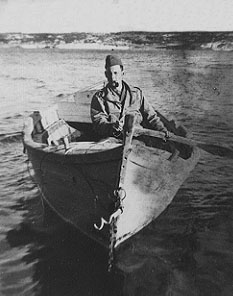

But in his earlier, happier days, when he felt like talking, I was always the one with the eager ear for his war stories. Oh, he would hold me spell bound with his tales of his experiences, as he would try to explain to me what it was like to have bullets whistling about him as he ferried supplies to forward areas of battle. He once gave me a small black and white photograph of himself taken in North Africa standing next to a plam tree that had been decapitated by machine gun fire. There he stood, my hero, clad in his khaki uniform and helmet -- proof that his war stories were true. I treasured that photograph and carried it around with me for years.

Toward the end of his life, when his illness had sapped his strength, I drove him, his wife Dolores and his cherished little girls, Sylvia and Sheila, down to the beach at Hilton Head Island, South Carolina. By this time, he understood the true nature of his illness, and he had begun to plan for the inevitable. He had just bought a Chevrolet -- used, but still newer than the one they had before -- and was able to insture it so that when he died it would be paid for. The Lincoln Mercury dealer in town knew of his terminal condition, but insured it anyway as a favor to him and to our family. Once seaside, my aunt brought out a picnic lunch, and we sat Uncle Lat in a beach chair facing the ocean. He was so weak he could barely move unassisted, but just being there and seeing the water again made him happy. I can still see his gaunt face in my mind's eye as he summoned the biggest smile he could muster. I believe that was the last time my uncle ever left home, except to return to the VA Hospital for treatment, and then to die.

In his final days, Uncle Lat was in constant pain from shingles, and eventually developed the pneumonia that took his life. He died in the Augusta VA Hospital on February 8, 1968, and was buried in the Ladeveze family plot in Augusta. At his funeral, his wife Dolores requested that the large blue and white Masonic symbol placed on top of the coffin for the service be placed inside the coffin when it was closed. The funeral director, Robert Brooks, complied with her wish, even though this was unplanned, the symbol being a prop intended to remain with the funeral home for reuse. I attended the funeral in Aiken, but I was not present at the graveside for his burial service at Cedar Grove Cemetery in Augusta, Georgia.

In looking back at what I know of Uncle Lat's life, I am faced with the realization that we all do what me must. All we can do is the best we can under our particular set of circumstances. Personally, I believe life dealt Uncle Lat a bad hand, but he struggled throughout his life to make the best of it, and for that he is to be commended. His two most important treasures, his girls, remained always at the forefront of his plans, and I am certain he would be extremely proud of them today.

After that rather lengthy, but necessary digression, I now return to me. As my age increased, so did my responsibilities at the store. By junior high school, I had added to the menial tasks of sweeping and mopping floors that of washing prescription sample bottles for reuse. This is something that would be frowned upon today, and for obvious reasons, but during the 1950s we did it, and we were able to reuse those 4 ounce and larger bottles for liquid prescriptions. And when I obtained my drivers license, I also began to share in the chores of going to the post office to check the mail, making bank deposits, and prescription delivery.

It was about this time, too, that I began to help my father fill prescriptions. I don't remember it being difficult to pick up as a skill. I watched him, asked questions, and had him check my work when I was done. My father was very patient with me, but he was also very thorough, and in a business that does not allow for mistakes, he taught me well. Even though he had been a pharmacist for many years by this time, he always had somebody else check his work because he realized something about human nature that always kept him on his guard. Sometimes, he would often tell me, what you think you see is not what is actually there. No matter how careful you are, you can make a mistake, because what you think you see the first time you look at a prescription, you are likely to see the second time, or the third as you check it. Better to have a set of fresh eyes check your work, just in case what you saw the first time was incorrect. In my subsequent training and experience in Navy pharmacy, I have never had anyone else tell me that, but it is true, and I have never forgotten it. In my own teaching stint in the Navy's Pharmacy Technician School, I passed that idea along. My father was an exceptional man in many ways -- very professional and businesslike. More about him later.

My Uncle Charles C. Johnson, however, was the actual business head of the operation. He was born October 13, 1906, the second oldest child in the family. With the untimely death of his older sister Mamie (Mary Jane Johnson Jones) in childbirth on August 13, 1937, he was left the oldest, and he quietly accepted this role. It was he who kept the books, managed payroll, negotiated bank loans and made most of the business decisions. Even so, he did his share of the other work. He filled new prescriptions, did refills, ordered and shelved merchandise, and thoroughly enjoyed interacting with customers. He was gregarious, and in every respect a fine man, but there was one quirk in his personality he evidently inherited from his father, and that was a tendency, at times, to treat certain people in a condescending manner. He didn't make it a habit, and I suspect he only did it when he felt mischievous, but was good at it when the mood hit. It was standing knowledge in my family that my grandfather--his father--had a habit of patronizing people at times, but he was intelligent enough to do it with class, often without the person realizing he had actually been insulted. Uncle Charles could also do that and get away with it, especially with people who had little education. But he was not by nature malicious, as I understand his father could be at times.

As for his own education, Uncle Charles attended elementary school in Aiken, finished high school at Haines Institute in Augusta, then went off to Howard University, where he and my father finished the pharmacy program together in 1932 with PhC (Pharmaceutical Chemist) degrees. He and my father had their pharmacy licenses prominently displayed over the prescription counter throughout the time the drug store was in operation. Interestingly, their licenses listed the score each made on the Pharmacy Board examination, and I remember Uncle Charles' score being a few points higher than my father's, though I seem to remember both scores being in the middle to high eighties.

Uncle Charles was also a Master Mason and, as his father had been before him, was active in the Royal Arch and Masonry at the Consistery level (32nd Degree). He was masterful in his command of Masonic ritual and a true joy to observe at meetings. Over the years, he had held every office his local Lodge afforded, including Past Master, and he was a member of the Order of the Eastern Star. Ironically, and as history has a way of repeating itself, I often found myself driving him to his Masonic meetings in Columbia as a youth, just as he had done for his father.

I never knew Uncle Charles to have a hobby or an avocation, unless it was carpentry. He enjoyed building things with wood, and he seemed happiest when he was working with his hands, often involving himself in repair projects around the store. To me, at least, it seemed he would rather do that than fill prescriptions.

By way of general physical description, Uncle Charles stood about 5 feet, 6 inches tall, had straight dark brown hair as a young man, brown eyes and a fair complexion. He was just a little heavier than Uncle Lat, but he, too, didn't have to worry about his weight. I estimate 165 pounds at most. Of the four male children, I believe his facial features most closely resembled those of his father. Especially was this true of his nose.

Uncle Charles had property in Graniteville, South Carolina, about 6 miles or so from Aiken, and I would often go with him in the 50s to see Nettie Brooks, the huge black woman who ran a beer garden on his property. It was truly a rough and rowdy crowd she catered to, and it was in her nightclub I first heard down home, gutbucket blues as it emanated from the 78 rpm records on her jukebox. If Uncle Charles was ever uncomfortable during those visits, it certainly didn't show. I suspect he rather enjoyed those brief encounters with the seamy side of life, I imagine because it was so different from the life he led.

Uncle Charles' children, Charlese and Charles, never took a serious interest in working in the store. His wife Mabel, on the other hand, became more actively involved in the business as time wore on. In the final years of the store, she threw herself wholeheartedly into the collection of accounts, delinquent and otherwise, much to the annoyance of many customers. The store lost business during those years because of her behavior, but Uncle Charles seemed unable to control her. I often found myself sympathizing with him, simply because he was such a nice person, and she seemed to take pleasure in walking all over him at every opportunity. It was not unusual for her to come through the side door of the pharmacy shabbily dressed in one of Uncle Charles' old shirts and wearing a pair of Uncle Charles' old slippers two sizes too large for her feet, and for her to pick a verbal fight with anyone around. In incredulous contrast, her command of English was always precise and correct, indicative of the Master's she held in Education, and she could be very amicable when it suited her purpose, although she was most often extremely difficult to get along with. I tried to limit my contact with my dear Aunt Mabel.

Uncle Charles, however, was as completely different from his wife and night and day. He had a golden heart and an overall positive outlook on life that never wavered. And as my godfather, he was always very supportive of me, taking the time to encourage me in Boy Scout activities (something he believed in and supported with his time), and he sat on the examining board when I went up for Star rank. When I wanted to join a local unit of the Civil Air Patrol, he took me to the man in charge of that unit, even though we both realized the Patrol was white only at the time, and I wouldn't be given a chance to join. That particular day, he put that man on the spot, making him explain exactly why I wouldn't be allowed to join. I still didn't get in,but I'll always respect him for having that much courage. Also, it was he who took me in for my drivers license test after I failed parallel parking the first time, and I can not say for certain today that he was not responsible for me getting my license. And Uncle Charles was later instrumental in encouraging me and standing by me when I joined the Masons, then later the Royal Arch Masons and the Consistery.

In those early years, being around him was truly like having a second father. He called my father "Make," and me "Little Make" at first, but later he would also call me "Make." Always ready with a smile and hearty greeting for friends, he was a most pleasant person to be around. He enjoyed smoking cigarettes from the earliest I can remember, and continued to smoke until about a year before his death. I have often tought to myself what a useless undertaking it was for him to give it up (on the advice of his doctor) at his advanced age. He died on August 20, 1987, but not from smoking -- from prostate cancer, instead.

Before I leave Uncle Charles, there is one incident that comes back to me from the mid 1960s, worth mentioning because it is one of the more dramatic examples of service he and the store rendered to the community over the years. Owing to the drugstore's location -- it was about three blocks from the beginning of Aiken's usual parade route -- this particular 4th of July morning most of our customers were either in the front of the store looking out, or outside awaiting the parade. I had gone upstairs just outside Dr. Cherry's dental office to stand at a glass-paned door that overlooked the street so I'd have a better vantage point. Shortly after the parade began at 11 a.m., the procession came into view, with marching bands and decorative floats. One float in particular, with a Civil War theme, even had a real cannon on board which the attendants were stoking with gunpowder. As chance would have it, just as it passed the store, the cannon fired, letting out a tremendous report. In a split second, the resulting tongue of flame leapt all the way to the float immediately in front of the cannon, where a waving "Miss somebody" sat smiling on her display. In the blinking of an eye, the girl's dress went up in flames, and she bounded off the float and ran, screaming hysterically, into our drugstore. Uncle Charles, in a remarkable display of clearheadedness, grabbed a blanket from somewhere (I still have no idea where), wrapped the girl in it, flaming dress and all, and put out the fire, thus saving her from extensive burns. As far as I know, he never even got a thank you for that act of heroism. It certainly never made the local paper. I dare say few people remember that incident today, but it lives on in my memory as a special day in the life of the store

The final one of the three brothers who operated Dr. C. C. Johnson's Pharmacy during my lifetime, and the one to whom I have made only a brief allusion, was my father. I saved him for last because he was the one person most responsible for providing me with this drug store experience, and the one to whom I am most grateful. Rather than repeat the information on him, please see my Tribute to My Father page.

Return to History Of Dr. C. C. Johnson's Drugstore.

Last Reviewed: 15Jun03