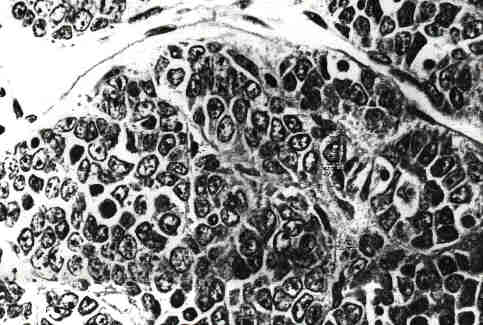

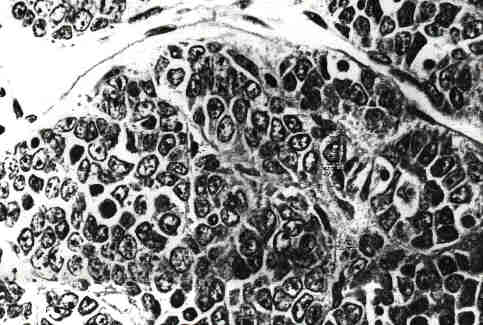

FIG. 1. Small cell carcinoma of the ovary (x 400).

DISCUSSION

Small Cell Carcinoma of the Ovary with Hypercalcemia: Report of a Case of Survival without Recurrence

5 Years after Surgery and Chemotherapy

William C. Reed, M.D.

Small cell carcinoma of the ovary is a rare and often fatal malignancy which occurs most often in young women. When this tumor produces a syndrome of hypercalcemia, it is often the effect of that endocrine disorder for which the patient seeks medical attention.

A 31-year-old woman, gravida 1 para 1, was admitted to the hospital with a 6-week history of continuous nausea. For 1 week prior to admission she had been vomiting several times per day including waking at night with vomiting and dry heaves. She had noted some vague pelvic pain, and at the time of her admission was severely constipated, her last bowel movement having been a week previously. Additional symptoms included light flashes in her visual periphery, intermittent confusion, and difficulty speaking. She was first seen in a walk-in clinic where on laboratory screening she was found to have a serum calcium level of 16.0 mg/dl (8.4-10.2).

The patient's past medical history was one of good general health. Five years prior to her present admission she underwent a diagnostic laparoscopy for suspected ectopic pregnancy with the finding of a left ovarian cyst presumed to be of corpus luteum origin. No biopsy was taken and the cyst resolved spontaneously. Previous surgery also included a breast biopsy for benign disease and a cesarean section. An annual exam 1 year prior to admission was reportedly negative for any pelvic pathology. She was not taking any medications.

Physical examination demonstrated an ill-appearing woman with a pulse rate of 116 and evidence of dehydration. Pelvic examination was inconclusive. There was some suggestion of an ill-defined pelvic mass. Rock-hard stool in the rectum further hampered pelvic assessment. Deep tendon reflexes were brisk.

Laboratory studies demonstrated a glucose of 110 mg/dl (70-105), blood urea nitrogen 27.2 mg/dl (6.0-19.0), creatinine 1.3 mg/dl (0.6-1.2), alkaline phosphatase 120 u/liter (29-117), chloride 97 mEq/ml (100-112), total bilirubin 1.3 mg/dl (0.0-1.0), LDH 286 u/liter (122-220), total protein 8.2 g/dl (6-7.8), globulin 3.6 g/dl (1.5-3.5), C-terminal parathyroid hormone 130 pg/ml (50-340), 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D 31 pg/ml (20-76), CEA 0.5 (<2.5), and c~-fetoprotein 4.8 (<8.5). Chest X ray, skull series, and plain films of the abdomen were all within normal limits. A bone scan showed increased uptake in the region of the sella. Pelvic ultrasound revealed an 11-cm complex mass with both cystic and solid components of probable ovarian origin. Computerized tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a pelvic mass extending to the level of the pelvic brim measuring 6 x 8 x 10 cm with well-defined rounded margins and a multiloculated cystic, low-density central area. The uterus was normal in size and deviated to the right. The left fallopian tube extended toward and appeared contiguous with the left margin of the mass. An ECG showed left axis deviation, a shortened QT interval of 0.28, and left anterior superior hemiblock.

Preoperative efforts to lower her serum calcium consisted of intravenous infusion of 3-5 liters of normal saline per day, intermittent furosemide, and etidronate 400 mg intravenously over 2 hr on three consecutive days. SoluMedrol 60 mg q 8 hr was also administered. Despite these measures, the serum calcium remained in the range of 14 to 16 mg/dl. The patient was then started on intravenous infusions of mithramycin 1 mg/day for three consecutive days at the end of which the serum calcium had dropped to 9.4 mg/dl and the patient was taken to surgery.

At surgery there was a left ovarian mass measuring 12 x 8 x 8 cm. The mass had a bosselated surface and appeared encapsulated. Subsequent microscopic examination showed no invasion of the capsule, but rupture with some spillage occurred while delivering the tumor out of the pelvis. No tumor adhesions were noted. No pelvic washings were obtained. After spillage from the ruptured cyst occurred, the pelvis was copiously irrigated with saline. A total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic and periaortic lymph node sampling was carried out. There was no evidence of tumor beyond the ovary, FIGO Stage Ic. The cut surface of the ovary consisted of areas of yellow-tan tissue with scattered small- and medium-sized cystic spaces separated by fibrous septae. Microscopically, the tumor formed solid sheets, trabecular cords, and nests of small cells. Individual cells contained medium to small nuclei, many with prominent nucleoli. The mitotic rate was high. Immunohistochemical studies for antibodies to low-molecular-weight cytokeratin, vimentin, epithelial membrane antigen, neuroendocrine protein, carcinoembryonic antigem leukocyte common antigen, and neurospecific enolase were all negative. All of these findings were consistent with the diagnosis of small cell carcinoma (Fig. 1). Representative sections were examined by Dr. Robert E. Scully who concurred with this diagnosis. Following her recovery from surgery, the patient was treated with three cycles of chemotherapy consisting of cis-platinum 150 mg x 1 dose and etoposide 150 mg daily x 3 days in cycles 1 and 3, and cis-platinum 30 mg daily x 5 days, and etoposide 150 mg daily x 5 days in the second cycle. Bleomycin was given in a dose of 30 mg/week. A fourth course of therapy was not initiated due to toxicity consisting of severe and prolonged nausea, vomiting, and dehydration. Since then, she has been followed with CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis, and serum calcium levels which have returned to and have remained in the normal range. She has remained well, with no evidence of recurrence for 5 years at the time of this writing.

FIG. 1. Small cell carcinoma of the ovary (x 400).

DISCUSSION

Dickersin et al. [1] first described small carcinoma of the ovary with hypercalcemia in 1982. His series consisted of 11 patients whose ages ranged from 13 to 35. Presenting symptoms included lower abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Serum calcium levels ranged from 13 to 18.0 mg/dl. At surgery, large ovarian tumors were found, all of which were unilateral. Peritoneal spread was noted in three patients. A hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was done in six cases and unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in four. Treatment in the remaining case was not known. Only one of these patients survived beyond 5 years without evidence of recurrent disease. Seven of the 11 died of disease within 1 year of diagnosis. Four patients received postoperative radiation therapy, and four were given adjuvant chemotherapy. Further evidence of the aggressiveness and lethality of this tumor is related by Patsner et al. [2] who report death within 6 months of diagnosis in two young women ages 12 and 18, both of whom were treated for advanced disease with cytoreductive surgery followed by aggressive radiation and chemotherapy. Similarly, Senekjian et al. [3] reported five cases of small cell carcinoma of the ovary in adolescent girls and women whose ages ranged from 10 to 42. These patients were treated with aggressive polychemotherapy consisting of vinblastine, cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, bleomycin, doxyrubicin, and etoposide. Despite some evidence of short-term response, four of the five patients died within 11 to 18 months of the initial operation. One patient was alive with no evidence of disease 29 months after diagnosis. Severe toxicity was encountered with this aggressive chemotherapy including myelosupression, nausea and vomiting, and severe stomatitis. Two patients had paraneoplastic or toxic motor neuropathy.

The histogenesis of small cell carcinoma of the ovary has been studied extensively in the small series reported by Dickersin, Ulbright, and Aguirre [1,4,5]. Ulbright et al. [4] studied the clinical, pathologic, ultrastructural, and immunohistochemical features of small cell carcinoma of the ovary. Six cases involving young women ages 10 to 24 were included, two of which had associated hypercalcemia. All of these patients had a rapidly fatal course despite aggressive treatment. Four of these patients presented with stage III disease, and two with stage Ia, and Ic respectively. Microscopically the tumors were consistent with those described by Dickersin et al. [1]. The age distribution of the patients and the immunohistochemical characteristics of the tumors led these investigators to conclude that small cell carcinoma is most likely of primitive germ cell origin. Aguirre et al. [5] studied and compared the immunohistochemical staining features of 15 small cell carcinomas, 15 juvenile granulosa cell tumors, 15 adult granulosa cell tumors, and 5 Sertoli cell tumors. Their findings did not give a clear indication of any specific cell as the likely cell of origin for these rare tumors. More recently, Eichorn et al. [6] studied the DNA content of ovarian small cell carcinomas of the hypercalcemic type. Their finding was that 23 of 25 specimens of paraffin-embedded tissue evaluated by flow cytometry revealed diploid DNA. The remaining two specimens could not be interpreted. In contrast, subjecting other ovarian tumors to the same analysis revealed significant degrees of aneuploidy, from 20% in adult granulosa cell tumors, to 100% in dysgerminomas, and yolk sac tumors. This finding casts considerable doubt on the theory that these tumors are likely of germ cell origin, and tends to favor a sex cord origin.

It is not within the scope of this report to attempt to explain the etiology of the hypercalcemia associated with this malignancy. Suffice it to say that when it is present, it is often the cause of the patients presenting complaints of nausea and vomiting. The observation that elevated calcium levels return to normal after removal of the tumor mass suggest that the tumor itself produces a hypercalcemic factor. It has also been noted that a return of elevated calcium levels have been a reliable indicator of recurrent disease [1,7]. It should be noted, however, that while reappearance of hypercalcemia is likely to be associated with recurrent disease, normal calcium levels do not rule out recurrence. Long-term disease-free survival with this tumor is uncommon, but as is the case with this patient seems improved if stage I disease is present and treated aggressively by total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy [1,3].

The rarity of small cell carcinoma of the ovary, and its generally poor prognosis, has resulted in a paucity of recommendations as to any promising adjuvant treatment. A few generalizations, however, seem warranted. There appears to be no place for conservative surgery regardless of early stage, or the often young age of the patient. Poor survival rates, even in stage I disease, would argue for further efforts to establish an efficacious chemotherapy protocol. At present there is no indication as to the origin of these tumors, although flow cytometry findings are most similar to tumors of sex cord origin. Anecdotal cases such as this, while of little significance in themselves, might collectively help point the way toward an improved treatment regimen for this often devastating disease.

REFERENCES