Persons looking for the initial cause of the war must look earlier than 1832. Many historians point to the disputed Treaty of 1804, where the Sauk and Fox tribes (essentially co-existing in the Rock Island area of Illinois) were informed that their lands had been ceded for a pittance to the U. S. by an agreement signed by a native delegation led by Quashquame.

The Sauk and Fox were allowed to live on the land until it was sold, which didn't happen until the so-called "Lead Rush" of the 1820s. Moreover, the Sauk allied themselves with the British during the War of 1812, and war parties under Black Hawk won victories and committed depredations on Americans. This did not endear the tribe or Black Hawk himself to the local American population.

The Sauk and Fox were allowed to live on the land until it was sold, which didn't happen until the so-called "Lead Rush" of the 1820s. Moreover, the Sauk allied themselves with the British during the War of 1812, and war parties under Black Hawk won victories and committed depredations on Americans. This did not endear the tribe or Black Hawk himself to the local American population.

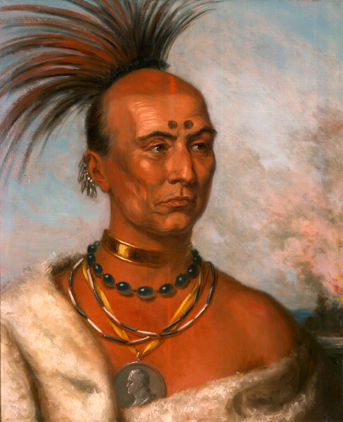

During the War of 1812, while Black Hawk was away from Saukenuk (the principle Sauk village and tribal center) a young man named Keokuk usurped Black Hawk’s place of leadership among the Sauk. Keokuk emerged as a spokesman and negotiator for the Sauk-- and the Americans did everything they could to encouraged his participation in councils and treaty-making. After a tour of the Eastern United States, Keokuk observed first-hand the power and wealth of American society. He soon came to realize that his people could not hope to prevail in a prolonged struggle with the United States. Keokuk then resolved to negotiate the best deals possible for himself and his people-- even if it meant removal from their ancestral lands.

By 1831, the discovery of lead ore and the resulting surge of American emigration into northwestern Illinois and southwestern Michigan Territory (today's Wisconsin) prompted the land sales stipulated by the Treaty of 1804. The Sauk and Fox were forced to remove across the Mississippi, leaving their villages, ancestral lands, and cornfields still planted with corn behind. Keokuk urged a peaceful removal, but Black Hawk led a contingent of Sauk and Fox angry with the removal back across the river into Illinois. Black Hawk's return across the Mississippi promoted the raising of the militias in both Illinois and the Michigan Territory. Black Hawk backed down, and signed a treaty (known later as the "Corn Treaty") whereby he formally recognized the validity of the Treaty of 1804, and the requirements of native removal after land sales. He then moved across the Mississippi into present-day Iowa, and made arrangements for his bones to be returned to Saukenuk after his death.

But the winter in Iowa 1831-2 was a hard one and the food ran out in the Sauk and Fox camps. Murmurs turned to uproar and a segment of the Sauk and Fox appealed to Black Hawk to again return across the Mississippi to their former homes and cornfields. Likewise, advisors like Ne-a-pope (the Number One Civil Chief of Black Hawk’s principle group of followers— known as the "British Band") and White Cloud, the Winnebago Prophet, urged the movement based on assurances of support from the British at Fort Malden and a rising of native tribes like the Winnebago and the Potowatomie that would ally with the British Band.

On April 5, 1832, Black Hawk disregarded the treaty he signed the previous year, and led a party of some 450 well-armed, mounted warriors and their families, (about 1,000 souls; approximately 17% of the estimated Sauk and Fox population at that time) plus about 10 lodges of the Kickapoo, across the Mississippi into Illinois. Governor John Reynolds immediately appealed to the U. S. Army for help and again called up his state's militia. Some historians like Dr. Paul Sutton have incorrectly characterized this as a "political" move on the part of Reynolds. In reality, this was the third time the militia had been called up to deal with an Indian threat within a span of five years.

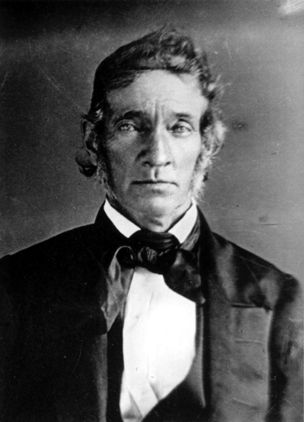

Another erroneous claim is that the Americans made no attempt to peaceably negotiate Black Hawk's return across the Mississippi River. In truth, an effort was made-- one in keeping with the established custom and tradition of negotiating with native tribal leaders. On April 23, Henry Gratiot, U. S. Indian sub-Agent, his secretary, and a delegation of Winnebago tribal leaders tried to meet with Black Hawk at White Cloud's village, Prophet's Town. There, boisterous young men brandishing weapons and kept Gratiot kept a virtual prisoner in his lodge until a "ransom" of tobacco was paid by Gratiot's secretary. The white flag carried by Gratiot upon approaching Prophet’s Town was pulled down, and a British ensign raised. Eventually, Gratiot met with Black Hawk in council and delivered the message of General Henry Atkinson, U. S. Army. The message essentially demanded that Black Hawk and his band return to Iowa peaceably, or face armed conflict.

Another erroneous claim is that the Americans made no attempt to peaceably negotiate Black Hawk's return across the Mississippi River. In truth, an effort was made-- one in keeping with the established custom and tradition of negotiating with native tribal leaders. On April 23, Henry Gratiot, U. S. Indian sub-Agent, his secretary, and a delegation of Winnebago tribal leaders tried to meet with Black Hawk at White Cloud's village, Prophet's Town. There, boisterous young men brandishing weapons and kept Gratiot kept a virtual prisoner in his lodge until a "ransom" of tobacco was paid by Gratiot's secretary. The white flag carried by Gratiot upon approaching Prophet’s Town was pulled down, and a British ensign raised. Eventually, Gratiot met with Black Hawk in council and delivered the message of General Henry Atkinson, U. S. Army. The message essentially demanded that Black Hawk and his band return to Iowa peaceably, or face armed conflict.

Black Hawk steadfastly refused to return. He indicated that his "heart was bad;" that he was going sixty miles up the river, and if molested he would fight. Later, White Cloud secretly warned Gratiot that a party of young Sauk men were coming for him, and that the Indian Agent and his secretary should leave Prophet's Town quickly by canoe. The Sauk men discovered his departure. Gratiot paddled for his life for Fort Armstrong, pursued by Black Hawk's young men in canoes. A wide-eyed and exhausted Gratiot arrived at Fort Armstrong and reported that in his opinion, no peaceful settlement with Black Hawk or his band was now possible.

To Black Hawk's dismay, the assurance of additional native support never materialized. Tribes like the Potowatomie and Winnebago were sympathetic, but refused formal alliances with Black Hawk for fear of American retaliation. In fact, Black Hawk was in the midst of a dog feast and further talks with Potowatomie tribal leaders on May 14, when the presence of a 275-man militia battalion was reported just a few miles away at Old Man Creek (present-day Stillman Valley, Illinois) Ne-a-pope sent three men with a white flag to call a parley with the Americans, while Black Hawk sent five warriors to a ridgetop that overlooked the American camp to watch the proceedings.

Things went bad from the start. The three Sauk with the white flag were brought to the militia camp, but the Sauk spoke no English, and the militiamen spoke no Sauk. Then, Major Isaiah Stillman's men spotted the warriors on the ridgeline, and immediately suspected a trick. One American turned and shot and killed one of the Sauk parley party in cold blood. The other two Sauk eventually got away. In the meantime militiamen (some charged up with whiskey) took off on horses after the five warriors on the ridgetop. Fighting ensued, and the warriors galloped away to report the developments to Black Hawk.

Things went bad from the start. The three Sauk with the white flag were brought to the militia camp, but the Sauk spoke no English, and the militiamen spoke no Sauk. Then, Major Isaiah Stillman's men spotted the warriors on the ridgeline, and immediately suspected a trick. One American turned and shot and killed one of the Sauk parley party in cold blood. The other two Sauk eventually got away. In the meantime militiamen (some charged up with whiskey) took off on horses after the five warriors on the ridgetop. Fighting ensued, and the warriors galloped away to report the developments to Black Hawk.

Upon hearing the news, an incensed Black Hawk scraped together forty mounted warriors (the rest of his men were apparently off hunting) and charged at the Americans—- an attack he thought would be his last. In the gathering darkness, militia resistance crumpled, then collapsed. In an unreasoned and panic-filled route, the militia (save for Captain Adam's brief rear-guard stand on a small knoll where the present-day monument stands) fled from the field. Twelve militiamen were killed and their bodies later mangled by the victorious Sauk. But the reports the flooded the region spoke of hundreds of casualties at the hands of thousands of bloodthirsty Indians.

Panic swept the land... and Black Hawk's War was on!