Weight of fruit removed from the tree = 141 lbs.

Weight of fruit sample = 3.7 lbs.

Number of fruits in sample = 236

Weight per fruit = 3.7 lbs. 236 = 0.015677 lbs.

Total fruit removed = 141 lbs/tree 0.015677 = 8994

Total fruit per tree = 8994 1.05 = 9444

Pounds of mature nuts per tree = 9444 nuts/tree 57 nuts/ lbs. = 165 lbs/tree

Production per acre = 165 lbs/tree x 27 trees per acre = 4455 lbs/acre

The same procedure was used to estimate potential production from other trees in this orchard. Again production was calculated to be about 4000 pounds per acre or greater. As experience has well illustrated, a Wichita crop of this magnitude is destined to be junk. Furthermore, in the region where this orchard is located, any nuts that might have good quality will germinate prematurely at this level of fruiting. Thus, the decision was made to thin the fruit on excessively fruiting trees down to an equivalent of 2000 lbs. per acre. Fruit on trees judged to be fruiting at less than an equivalent of 2000 pounds per acre were not thinned. The 2000 production level was selected because above this level nut quality rapidly decreases (Sparks and Weber, NNGA 84:146-147). Although 2000 pounds per acre may be a target level for good quality, it may be too high for adequate return bloom. This is yet to be determined.

At harvest, nut production was about 1600 pounds per acre. Production was less than 2000 pounds because trees on which the fruit was not thinned were fruiting at an equivalent less than 2000 pounds per acre. Nuts per pound averaged about 51 and percentage kernel was about 61 percent for Wichita. Percentage kernel for Western Schley was 57 to 58 percent. Shuck decline was not a problem. Premature germination was less than 1 percent. Thus, fruit thinning resulted in a high production of excellent quality nuts. Hopefully, return bloom in 1996 will be sufficient for another year of high production. Even if return bloom is not improved, fruit thinning remains a useful tool in that it can be used to convert a potentially poor quality crop into one of excellent quality.

Fruit thinning is being successfully used in Oklahoma on a commercial basis to improve the nut quality and, hopefully return bloom, of Peruque, Barton, Shoshoni, and Mohawk (M.M. Smith, personal communication). In Georgia, fruit thinning has improved fruit quality on Stuart, Shoshoni, and Mahan. This season, 400 acres of Wichita were fruit thinned in California.

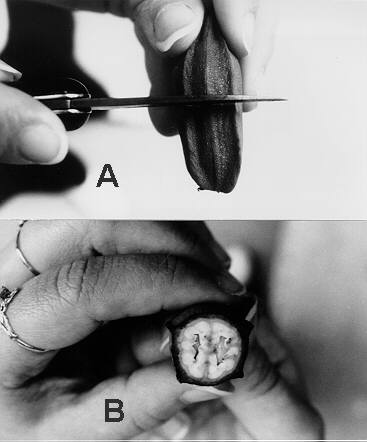

There are some problems. The first is to convince yourself to try it. However, after experiencing one or more years of heavy crops that end with a lot of junk, the idea of fruit thinning becoming surprising more appealing. The major problems are visually deciding if a tree is fruiting excessively and how much fruit to take off. A visual image of an excessive fruiting tree is developed by studying the fruit set on the tree. If close to 100 percent of the shoots are fruiting and average cluster size is greater than three, the tree is definitely over fruiting. Once an image is fixed, it can be checked by going through the procedure previously described to determine the total number of fruits on the tree and the potential production per acre. Once the decision has been made to thin the fruit on a tree, the decision becomes how much to take off. Ideally, shaking should be terminated at the point where about 70 percent of the shoots are fruiting and cluster size averages about three. However, this cannot be determined while the shaker is in motion. Thus, a mental correlation has to be developed between the density of fruit on the ground and those remaining on the tree. This correlation can be developed by trial and error. Determining if the tree is over fruiting and how much fruit to take off requires a bit of art. Nevertheless, after some experience, the operator develops a "feel" and repeatability becomes good. Because experience is very important, using the same person to operate the shaker is essential.

Once you start fruit thinning, the question becomes did I remove too little or too much? If it is your first experience, the odds are that you did not take off enough. Nevertheless, either question can be answered by taking a few trees that have been fruit thinned and remove all the fruit on the tree. Determine the potential production per acre of these fruits as outlined above. The potential production should be fairly close to 2000 pounds per acre. If it is not, an adjustment in intensity of fruit thinning will be needed.

The pecan is a severe alternate bearer. Consequently, once a good return bloom occurs, removing a portion of the fruit later in the season is not exactly high on the priority list of most growers. Nevertheless, many pecan cultivars will over fruit and when this occurs poor quality is the rule. In such cases, there is little to lose by trying mechanical fruit thinning.