After the winter of 480-479BC the Greeks began to mobilise again, with their enemy still stationed north in Thessaly. The commander of the Persian forces, Mardonius, sent an envoy to Athens with a peace proposal stating that Xerxes had agreed to forgive the offences of the Athenian people, their city would not be attacked again and that the king would even pay for the rebuilding of the Parthenon if they accepted to submit to Persia.

At the same time this envoy, who was Alexander of Macedon (not Alexander the Great), approached Athens, so did ambassodors from Sparta. They had learned in general of what Alexander was going to propose, and they feared the Athenians might accept, turning disaster on themselves and the rest of the country.

These were very fair terms that Xerxes gave to Athens, and Alexander firmly encouraged them to accept. The response of the Athenians however, would change the entire outcome of the war.

"We know of ourselves that the power of Persia is many times greater than our own...Nevertheless in our zeal for freedom we will defend ourselves to the best of our ability. Regarding entering into agreements with the barbarian, do not attempt to persuade us to enter them, and we will not consent...As long as the sun lights the course by which he now goes, we will make no agreement with Xerxes. We will fight against him without ceasing, trusting in the aid of the gods and the heroes whom they have disregarded and burnt their houses and their adornments. Come no more to the Athenians with such a plea, nor under the semblance of rendering us a service, counsel us to act wickedly. For we do not want those who are our friends and protectors to suffer any harm at Athenian hands" (Herodotus, 8.143)

The Athenians thanked the Spartan envoys for their concern and told them to send their army as quickly as possible to support them against Mardonius, whose advance was inevitable after he received this reply from the men of Athens. The Persian army accordingly broke camp and advanced southward towards Athens with great enthusiasm. When they arrived as they had ten months earlier, they discovered the city completely uninhabited, captured it, and eventually burned it to the ground. The Athenians had sailed across to Salamis where they awaited the Spartan force, who were largely involved in constructig a wall across the Corinthian isthmus, the narrow strip of land that seperates the Peloponnese from the rest of mainland Greece. Eventually they realised it would only be to their disadvantage if they did not send help, and so the Spartans mobilised a force and advanced to meet the Athenians as well as contingents from the other city-states. Huge groups of men came from Boeotia and the Peloponnese to fight and their united army, now under the command of a Spartan named Pausanius, is estimated to have totalled around 110,000 men, the largest force ever assembled in the history of hoplite warfare.

Mardonius sent in a group of cavalry in an attempt to lure part of the Greek army into action but they were defeated. Pausanius desperately needed to find a better water supply for his army, so finally they descended onto the Boeotian plain much closer to the river. The enemies successfully attacked part of their supply train on the mountain and for the next few days minor confrontations took place, the Persians managing to poison the Greek's water supply.

After ten days they were forced to move back towards the mountain, and after being harrassed most of the day by Persian horse archers Pausanius feigned a retreat under cover of darkness. During the night however, the troops managed to split apart from each other and the less experienced men ended up pitching camp near the city walls. When morning arose the veteran troops moved back to reunite with the army and Mardonius, assuming the Greeks were fighting amongst each other when he saw them seperated, ordered an attack.

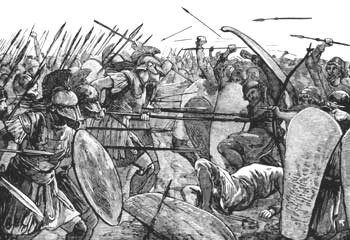

The Persian cavalry charged at the Athenian left wing before they had left the plain and seeing this, the younger troops at Plataea advanced to support the others. Mardonius then sent in the Greek mercenaries against the Athenians and fierce fighting now broke out between the two sides. He personally took command and advanced with his cavalry and infantry to attack the Spartans on the right wing, who became hard pressed as the Persians overwhelmed them. The other contingents of allies charged forward to help the Spartans and the enemy let loose on them with a hail of arrows, the Greeks defending as best they could with their shields.

Both sides continued the bloody fighting taking place and eventually the Persian commander Mardonius was killed by the Spartans who, spurred on by this and the arrival of their comrades, rallied together and continued the battle with renewed enthusiasm. The Persians on the left wing were pushed back by the onslaught, many fleeing after they realised their leader had died and subsequently their line began to crumble. The centre of the Persian army under Artabazos retreated and the Spartans pursued them back to their camp, while the Athenians on the other wing finally overcame their adversaries. The Spartan soldiers, although they lacked any kind of siege equipment, nevertheless proceeded to attack the enemy camp and when the rest of the allies finally joined them they destroyed it and killed most of the remaining troops.

The next move for the victorious army was to march north to the city of Thebes, who had given support to the Persians. Henceforth they laid seige to the city and after three weeks the Thebans surrendered by agreeing to hand over the men who had sided with Xerxes. The traitors then fell into the hands of Pausanius, who sent away his army and dragged them to Corinth where he personally executed them.

While the battle at Plataea was being fought, the remnants of the Greek navy were engaged in another conflict near the coast of Asia Minor. They had been anchored at Delos (a small island southeast of Athens) when they were approached by Ionian Greeks who promised to support them and revolt when they saw the approach of the navy. The ships sailed northeast to Samos and the Persians who were there sailed across to the mainland, joining the land forces of Xerxes on the Mycale peninsula.

The Persians held out for a while but eventually they retreated back into their camp. With the Spartan contingent yet to join them, the Greeks regrouped and rushed in at the enemy full of energy and enthusiasm, razing the Persian fortress to the ground. Most of the troops fled except the Persians themselves who continued defending against the hoplite onslaught, both sides inflicting heavy losses on each other until finally the Spartans arrived to join in and overcome what was left of the enemy.

The Ionian Greeks who had been sent to defend the mountain pass at first deceived the fleeing Persians about where to escape and then finally turned on them and killed many themselves. Herodotous notes the ironic twist of this Ionian rebellion and the revolt of the Ionian cities that led to the beginiing of the war.

After the allies had slaughtered most of the Persian forces at Mycale they went on to set fire to their ships, completely destroying what was left of the Persian fleet before sailing back to Samos. Here they decided against a proposal to evacuate all Ionian Greeks from Asia minor due to the ever present Persian threat, and decided instead that these states would enter into an alliance with Athens.

This alliance was known as the Delian League and throughout the next century it gradually developed into the Athenian Empire. After the Persians had been defeated, Athens emerged with the strongest fleet in the Mediterranean and was now at the head of a large confederation of Greek states. With this new sense of power and wealth coupled with her brilliant achievements during the Persian Wars, Athens was set to enter her so called 'Golden Age', which was brought to its height by the statesman Pericles. Over the next few centuries Athens became the cultural centre of the Greek world and the trade capital of the eastern Mediterranean. Science, art and philosophy began to flourish in Athens, perpetuated by men such as Socrates who taught his contemparies to question the world around them, and his followers Plato and Aristotle who laid much of the groundwork for modern science. The legacy of these ancient Greek thinkers and the achievements of the men whos culture had led them to defeat the largest empire of their time, was to become the foundation of Western society.