Directed by Mario O'Hara

Written by Mario O'Hara and Frank Rivera

Watch the movie online at TFC Now

Tatlong Ina, Isang Anak

Directed by Mario O'Hara Written by Mario O'Hara and Frank Rivera

Mario O'Hara's problem also happens to redound to the advantage of the sensible viewer. Either his films are worth sitting through from the beginning, or they warn you when a walkout is in order right from the start. Like his contemporaries when they were at or approaching their peak, O'Hara refuses to create any middle ground. Give any of his latest titles the benefit of a quarter hour or so, and you get assured that your money will be well-spent, or else you're given the option of refusing a nonsensical product.

He also seems to have found the ideal level of balance between working on a moderate budget yet making the most out of his own storytelling and his performers' histrionic potentials. Of particular interest over the years are his collaborations with Nora Aunor, and since his resumption of a directorial career during the 1980s, his battling average of roughly one well-made movie annually durin the past four years places him on par with no other local director except Peque Gallaga. For belligerence's sake, I suppose one could list down the latter's Virgin Forest, Scorpio Nights, Unfaithful Wife, and Once Upon a Time, and on the other hand name Condemned, Bulaklak sa City Jail, Bagong Hari, and add Tatlong Ina, Isang Anak as O'Hara's 1987 entry. Funny, as a final sidelight, how one happens to be identified with the art-for art's sake camp, while the other's associated with the art-for-social realism group--reflecting the earlier dichotomization between the public personae of Ishmael Bernal and Lino Brocka.

Tatlong Ina, Isang Anak isn't exactly a movie one should rave about indiscriminately--let's reserve that reaction for the first title that recalls the glory days of the early eighties. What Tatlong Ina does is provide a conventional good time (an irony for a film whose main characters are bastards, prostitutes, and gangsters)--and it sure reflects tellinglyon the state of the industry when a movie without any major ambition turns out to be in many ways the year's best so far.

The strange thing about Tatlong Ina, coming as it does from a filmmaker with a presumably progressive political orientation, is the property it shares with O'Hara's other recent good films; happy endings. (Of instructive sociopsychological value would be a comparison between these and Gallaga's serious efforts, which in contrast, except for Once Upon a Time, present a tragic resolutions.) Although suffused with film noir stylizations, especially in an overabundance of shadows and equally shady characters, O'Hara's films are entertaining to a degree that would definitely appal dogmatic proponents of social realism.

Never has his strategy become more obvious than in Tatlong Ina, where the happy ending finally ties in most satisfyingly with all the preceding developments. For all its realist imagery and subject matter, the movie is actually a proletariat's fantasy--a wide eyed daydream on how personal virtues operating within the proper social circumstances might just suffice in surmounting classic class conflicts.

As further proof of Tatlong Ina's political sophistication--or cleverness, depending upon your preference for the conventional-- the proletarian heroes encounter opposition from not only the orthodox villains, the bourgeoise, but also the so-called bad elements from whom they (the heroes) may initially be indistiguishable. The unlikely team of golden-hearted prostitutes and noble-minded bums subdue kid-snatchers and snobbish aristocrats through the use of force and charm respectively, with sexual attraction for each other and sympathy for a fallen comrade's love child as motivating force.

The abstraction does sound ridiculous, and isn't helped any by a series of coincidences that help propel the major characters toward ultimate victory. Only an artist's strong convictions in the face of all this silliness could create a semblance of integrity through technical consistency. Which luckily, O'Hara provides, by way of skills rooted in theater and well-hewn in cinema.

It wouldn't be too pedantic then to maintain that Tatlong Ina, as typical of O'Hara at his best, is an effective accumulation of finely observed and captured incidents with above-average performances providing the crucial credibility factor. His storyteller's sense of proportion fails him this time in only two instances, both of them admittedly minor in relation to the movie's overall accomplishment.

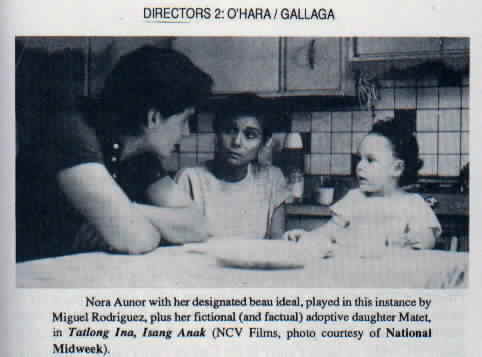

One is the use of the child as commentator, when her narrative functions at the start would have sufficed. Of course the expansion of the precocious Matet's role fits in with her lead-star status, which in turn has served as the movie's main come-on; but the problem of explaining real time--when, where, and why is she telling the story of her "mothers'" uphill struggles?--eventually emerges, and is never given even a perfunctory justification. Secondly, and more seriously for the film's narrative purposes, the story suddenly permutes into the standard (and, by now, quite kinky) Nora Aunor requisite of pairing off a mousy character with an extremely improbable mestizo-type; the fact that the Adonis in Tatlong Ina also happens to come from old-rich stock practically promises to be the movie's undoing.

To a certain extent this particular instance of indulgence is mitigated by O'Hara's bravura staging of the most original wedding sequence since such endings recently became de rigeuer once more in commercial romantic outings. To be sure, the mise en scene appears in this case to be simple enough; it is the working out of the various class reactions, specifically the reverse snobbery of the about-to-be-redeemed ex-prostitutes, that ensures that this wedding scene's reliance less on pomp than on circumstance will make acceptable its appendage to the movie.

The aforementioned reservations aside, Tatlong Ina can stake a short-term claim on memory, if only for its admirable exposition on the underworld milieu, comparable to the same director's prison portion in his loosely structured, but then it covers a whole lot more territory, and as explained earlier, its upbeat ending fits the entire schema less awkwardly than does the earlier work. If thsi presages a cautious breaking away from the predictable and admittedly tiresome traditions of social relevance in moviemaking, then O'Hara's next moves centainly merit closer attention.

2 September 1987, Joel David, The National Pastime Contemporary Cinema