Jean Mouin Main Page

BETRAYAL AT

CALUIRE

Impeding Disaster

June 21, 1943

Montluc Prison

The Urn No. 10137

Impending

Disaster

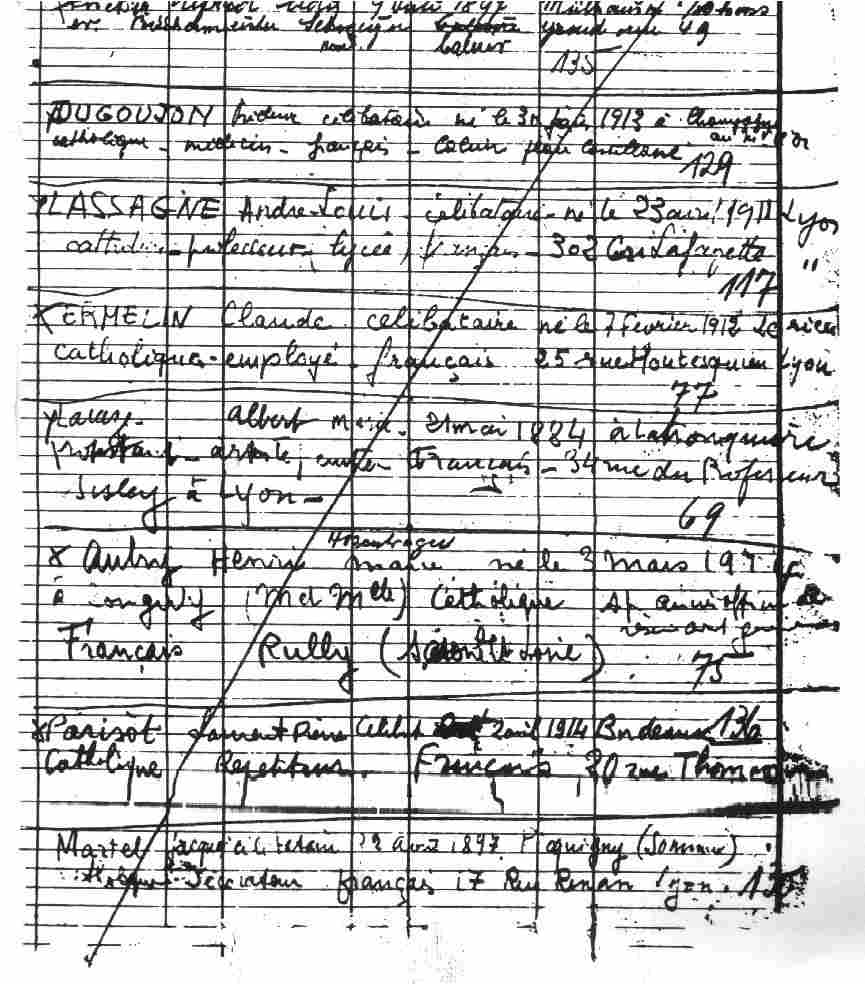

A diagram from the Kaltenbrunner Report on the Secret Army in May

1943

Klaus Barbie

René Hardy

Moulin's last letter his mother and sister, dated June 17,

1943.

On May 27, 1943, Dr. ERNST KALTENBRUNNER, who succeeded Richard

Heydrich as the chief of the Gestapo wrote a 28-page report to Foreign Miniser

Joachim von Ribbentrop. It landed on Hitler's desk two weeks before the

Caluire meeting.

It was the summary of their knowledge on the Secret Army, including

graphs and diagrams, which were drawn from material acquired by all the

Gestapo offices in France. Kaltenbrunner concluded that, with an invasion

by the British and Americans a distinct possibility, "the French Secret

Army is achieving increasing importance." In consequence, the Secret

Army and its political chief, Moulin became the prime target of the

Gestapo.

In their search for Max, the Gestapo in France hit a gold mine when

they arrested JEAN MULTON (alias Lunel), a member of Combat in Marseilles

at the end of April. Faced with torture and death, Multon agreed to

help the Gestapo infiltrate the Resistance, which resulted in the arrest

of some 100 resistants in the Marseilles region. Yet the worst damage was

still to be done. Multon was loaned to the Gestapo in Lyon, known as

the capital of French Resistance. [2]

Once in Lyon, Multon was instructed by Klaus Barbie,

the head of Lyon Gestapo (Section Four), to watch a mailbox used by

Combat unit for railroad sabotage known as

Résistance-Fer. The members of the group still at large were alerted that the box

was "burned", but Barbie thought that someone careless might use. And

amazingly someone did.

Near the end of May, General Charles Delestraint (alias Vidal),

commander-in-chief of the Secret Army met his chief of staff, HENRI AUBRY

(alias Thomas) to arrange a meeting with RENÉ HARDY (alias Didot),

head of Résistance-Fer to develope a master plan for

derailment of the French train system for D-Day. Aubry, preoccupied with his

ailing wife in Marseilles, told his secretary to draft and dispatch a

letter to Hardy. She wrote the letter "in clear", that is, in uncoded

French, then deposited it in burned letterbox. When she returned from this

errand and told him what she has done, Aubry expressed concern, yet did

nothing to warn Delestraint or Hardy. Why did she used a burned letter

box and send the message "in clear"? Why did not Aubry warn Delestraint

and Hardy? These questions have provoked bitter debate for years. All

that can be said with certainty is that the message was sent in clear

language to a buned letter box, an act of incredible negligence if not

treason. [4]

General Delestraint's Arrest

When Barbie read the letter, he was exhilarated: Didot was to was to

meet with Vidal, the head of the Secret Army at a Paris Metro station on

the morning of June 9, 1943.

On the evening of June 7, Hardy was going to Paris, but not for the

meeting with Delestraint. He never picked up the letter from the burned

box, so he did not receive Aubry's message. He had another appointment

with a member of his sabotage unit. However, when he boarded a train, he

found to his dismay, that he was assigned a bed in the same car as

Multon and his German handler, ROBERT MOOG. Moog noticed the "eye exhcange"

between Multon and Hardy, who knew Multon turned traitor. Hardy then

caught sight of LAZARE RACHLINE, a SOE agent, walking toward the

train. The Paris express that night seemed to be the "spy special."

Hardy, suspecting he had been fingered," strolled over to Rachline, asked

him for a light, and whispered over his cigarette: "Tell de

Bénouville that if anything happens to me, it's Lunel[Multon]'s fault."

Hardy was arrested in the train, and the two informers continued on

toward Paris to meet Delestraint. [4]

On June 9, Delestraint was approached by a Gestapo agent who posed as

Didot. In another security lapse, he confided in the double agent that

he had another meeting 30 minutes later at a nearby Metro station.

Delestraint was shoved into a car, which took him Gestapo's French

headquarters on the Avenue Foch. The Gestapo arrested Delestraint's lieutenants,

JEAN-LOUIS THÉOBALD and JOSEPH GASTALDO as an added bonus.

Moulin was devasted by the news, but he was fully aware that the

Gestapo was closing in. As early as May 7, he had written to de Gaulle

requesting deputies who could step in as his successors if he should be

killed: "I am now being sought by Vichy and the Gestapo who, as a result of

practices adopted by certain elements in the Resistance movements, are

fully aware of my identity and my activities. I am resolved to hold on

as long as possible, but if I disappear, I shall not have time to

notify my successors." [1]

Moulin felt it urgent to find Delestraint's successor at once;

otherwise rivalries over the Secret Army would erupt all over again. Moulin

wanted an immediate decision and called for a Secret Army summit. It was

scheduled to be held at a doctor's house in Caluire, a suburb of Lyon on

June 21, 1943.

June 21, 1943

The Caluire meeting remains one of most baffling mysteries in the

history of the French Resistance.

Somehow the Gestapo got a wind of the meeting; it was a catastrophe of

first order. Not only was the delegate of General de Galle and the

president of National Council of Resistance was nabbed, the entire

leadership of the Secret Army was decimated in a single scoop. Besides Mouin,

the seven arrested Resistance leaders included the likely successor to

General Delestraint as the head of Secret Army (Colonel EMILE

SCHWARZFELD), inspectors in both zones (RAYMOND AUBRAC for north zone;

ANDRÉ LASSAGNE for south zone), the chief of staff (Henri Aubry), head of

parachute operations (BRUNO LARAT), and Colonel ALBERT LACAZE, whom

Delestraint had asked to head the Section Four (logistics) at his Command

Headquarters. [8]

What is even more devastating to the French psyche is that this arrest

was no accident. The Gestapo raided the house looking for Max. It was

apparent that the meeting has been betrayed. But by whom?

The Caluire affair, as it is called in France, surpasses even JFK

assassination in the number and matter of surrounding conspiracy theories

and passion that they arouse.

This is mainly due to political machinations of both the right and left

to discredit each other with insinuation of the other side's supposed

role in the Caluire affair.

It is also due to clandestine nature of the Resistance. Since the

clandestine activities do not leave recorded documents, much of the what we

know about the Resistance in general and Caluire in particular are

based on oral testimonies of those involved. However, such personal stories

and recollections are notoriously unreliable. In case of Caluire, where

the question of treason looms large, it is even more so.

So what did really happen on that fateful day? With only unconfirmed

oral accounts few and far between, it is like trying to solve a jigsaw

puzzle with only few pieces in hand. But within the aforementioned

limitation of personal testimonies, the following account is generally

accepted as established facts.

A Meeting on Pont Morand

Lyon

Click the image to see the maps of Lyon and Caluire.

Dr. Dugoujon's house in Caluire.

It was in a preliminary meeting between Moulin, Aubry, Aubrac, and

Lassagne on June 19 that the the Caluire meeting was agreed on. The meeting

was to be organzied by Lassagne, who asked his friend Dr.

FRÉDÉRIC DUGOUJON to borrow his house on Place Castellane in Caluire.

They would pose as patients to avoid being noticed.

Aubry was nervous. With his boss, Frenay in London, he would be

expected to look after Combat's interests, but he was not confident that he

could handle Moulin by himself.

Next day in a fine Sunday morning, Aubry met GASTON DEFERRE, a

socialist resistance leader, and they strolled over to the Pont Morand to meet

Hardy. As they got near the bridge, they saw Hardy sitting on a bench

next to someone whose face was hidden by a widespread newspaper. When

Deferre agreed on next appointment and parted with Aubry, he walked away

wondering who had been siting next to Hardy, hiding his face in a

newspaper. He turned out to be Klaus Barbie. His Gestapo agents were

discreetly in position not far away. [4]

Hardy, who was interrogated by Barbie, never told his comrades about

his arrest. Later he claimed that he outfoxed Barbie to get released but

feared that if he revealed the arrest, he would be blamed for

Delestraint's arrest (which came after his arrest, but for which he was not

responsible). In those days, the Resistance justice for a suspected traitor

was swift and sometimes unfortunately flawed. So Hardy told Aubry that

he jumped out of the train when he spotted Multon, thus barely avoiding

the capture.

Oblivious of Hardy's recent arrest and Barbie's presence, Aubry told

him about the Caluire meeting. He was going to take him there to bolster

Combat's position even though he was not invited, a violation of a

basic Resistance security rule. Asked where and when the meeting was to be

held, Aubry said, "I don't know, but come to the bistro across from the

Caluire ficelle [funicular going from Croix-Rousse to Caluire]

at 1:45 p.m."

The next morning, June 21, when Aubry met Moulin, he tried to sound out

Moulin on Delestraint's successor, but Moulin would say nothing more

than to wait for the afternoon meeting to discuss the question. When they

parted, Aubry said not a word about Hardy coming to the meeting.

Moulin, having heard about Delestraint's planned meeting with Hardy,

had been telling people to avoid Hardy. If Moulin knew that Hardy was

coming to the meeting, the Caluire meeting would certainly have been

cancelled.

Colonel Lacaze's Premonition

The meeting was set for 2 p.m. at the house of Dr. Dugoujon. At this

point, only a few people knew about the address, and the attendees were

to arrive in three groups. Lassagne was to take Aubry to the meeting.

Larat would come with Colonel Lacaze. Moulin would escort Aubrac and

Schwarzfeld.

When Lassagne met Aubry at the funicular station, he found Hardy with

him. Lassagne later said at a hearing on January 21, 1946: "I had no

reason to be suspicious of Hardy or Aubry. All I said was that Max didn't

know he was coming and he might get annoyed. That it was unwise that

too many people should attend the same meeting. But Aubry said we should

have a quick first meeting with Hardy before going on to more important

subjects." According to Lassagne, Hardy also said, "I just want a quick

word with Max. I need to see him...I fixed it up with Max's secretary

[de Graaf]."

Lassagne boarded the furnicular first; he asked others to follow him in

the next car as a precuation. Lassagne arrived before others. Dr.

Dugoujon asked him, "Will there be many of you?" Lassagne answered, "No

idea." He then went off again to fetch Aubry and his surprise guest at the

end of furnicular. [8]

The second group to arrive at Caluire consisted of Larat, the head of

parachute drops and Lacaze, for whom this was the first clandestine

meeting. Lacaze was particularly anxious. He said later: "On June 17, the

gendarmerie captain of the Suchet barracks informed me, 'Be careful, at

Vichy, we know that the German police are on to something in Lyon.'" He

warned Larat that the meeting ought to be cancelled. He asked him to

call with a message, "No fishing tomorrow." if the meeting was cancelled.

No such phone call came.

Lacaze was still nervous. The colonel sent his daughter to reconnoitre

the surrounds of the house at Caluire, and around 9:00 a.m. she

delivered a letter to the house explaining that if her father did not show up

later, it would be because he was ill and could not get out of bed. As

time passed, Lacaze felt better and decided to attend the meeting. [8]

At doctor's house, the housekeeper has been told that Lassagne would be

arriving with a group of patients. The housekeeper, Marguerie Brossier,

took Lassagne's friends and Lacaze straight up to the bedroom on the

left as told. When Larat arrived, even the housekeeper thought that they

could not be that many and sent Larat into the patients' waiting room.

Larat said to Dr. Dugoujon, "I've come for a special consultation..."

Dugoujon sent him up to where the other four were already waiting.

But Moulin and his group did not arrive yet. Aubry and others were

surpirsed because Moulin had an obsession about being on time. To this day,

no one knows exactly why Moulin, Aubrac, and Schwarzfeld arrived very

late at 2:45.

"The Gestapo's Here!"

The question of timing is important because they were not the only ones

who arrived 45 minutes late. Barbie and his Gestapo were also late 45

minutes. The Gestapo raided the house just minutes after Moulin had

entered the house. If the Gestapo arrived in time, he would have seen the

police cars outside the house and continued on his way without coming

in. No one knows why Barbie arrived so late for the meeting if he had

known about it in advance as he claimed.

But what is even more surprising is that the resistance leaders waited

for 45 minutes in a violation of basic security rules. Nobody seemed to

remember the rule about never waiting more than fifteen minutes, a

golden rule in clandestine affairs.

In any case, according to Aubrac, Moulin arrived at 2:15 at the foot of

the furnicular, then they waited another fifteen mintues for

Schwarzfeld.

When they arrived at the doctor's house, the housekeeper ushered them

to patients' waiting room thinking that all the special patients had

already arrived.

Upstairs, Aubry recalled, "I heard the yard-gate squeak and glanced

down from the window, to see a whole lot of people in leather jackets. I

just had time to pull back and tell the others: 'We're done for, the

Gestapo's here!'" [8]

Hardy pulled out a pistol before the Gestapo burst in. Aubry recalled:

"We all told him to put it back. The bedroom door opened and Barbie

ordered in French, 'Hands up, German police!' He rushed over to me and I

was hit, my head bashed against the wall, and my hands forced behind my

back. [Barbie] said: 'Well now, Thomas, you don't look too good. You

were more cheerful yesterday on the Pont Morand, I was reading my paper,

but it was such nice weather I thought I'd leave you another day, since

I knew we would meet again today."

Aubry was astonished that Barbie not only knew his code name, which was

made up quite recently, but also knew about the Pont Morand meeting he

had with Hardy.

Downstairs, the Gestapo stormed in the patients' waiting room as well.

Moulin, who was still in the patients room, told the doctor, "My name

is Jacques Martel." He then handed Aubrac some papers from his jacket

lining and swallowed them together.

The prisoners and even the patients and doctor were rounded up. Moulin,

always careful, had taken the precaution of having another doctor write

out a letter telling Dr. Dugoujon that he was suffering from rheumatism

and probably needed a specialist. But the Gestapo took the precaution

of arresting everyone as well. [8]

Hardy's escape

They were all handcuffed with their hands behind their backs - all,

that is, except Hardy. Aubrac was immediately suspicious when he saw

Hardy. His suspicion was confirmed when Hardy was the only man who escaped

from the Caluire arrest. Dugoujon, who understood some German, recalled:

I heard them say there were no more handcuffs. So they tied

a leather strap to one of [Hardy's] wrists and a soldier held the end

of it. Outside the house when we were about to be loaded into their cars

this man without handcuffs suddenly pulled the strap out of the Gaurd's

hands, punched the soldier in the stomach and ran off. He ran very fast

across the square, dodging between the trees. Another soldier shouted

at him and then started shooting, but the man got across the square and

disappeared round the corner and none of the solders really searched

for him.

Hardy threw himself into a ditch after taking out his gun and shooting

back at the soldiers. But the Germans had a dozen prisoners to watch,

and abandoned the pursuit of Hardy, who got away by running down the

hill through the woods down to the Saône River.

However, Hardy was shot in the upper arm. He was soon arrested by the

French police, and was taken to a German military hospital to have his

wound treated. Yet Hardy, with his arm in a plaster cast, managed to

escape from the hospital as well by jumping out the window onto the roof

of a garage, and climbing over the hospital gate.

Montluc Prison

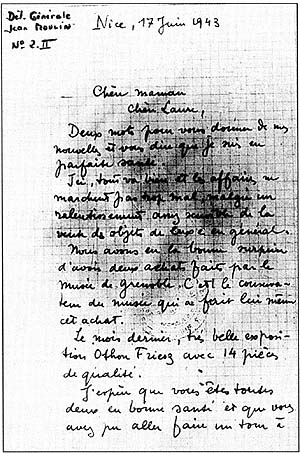

L'ecole du service de santé militaire, the Gestapo

headquarter in Lyon where Barbie conducted his interrogations.

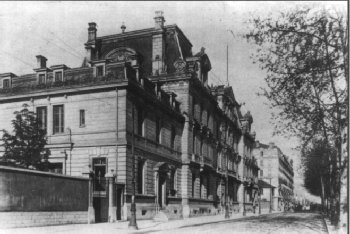

a page from Montluc Prison registry showing the Caluire arrest. At

bottom is Moulin's entry under the name of Jacques Martel.

a notice of the court martial and execution of a resistant named

Richard Henault.

a poster released by German authorities depicting the resistants as

criminals.

Christian Pineau

The top leaders of the French Resistance were now in the hands of the

Gestapo, but Barbie still did not know which of his prisoners was Max.

Those arrested in Caluire were first taken to Gestapo headquarters in

the Ecole de Santé Militaire, where they were lined up before

Barbie. Dr. Dugoujon recalled, "He walked down the line and asked each one

of us if we were 'Max'." The resistant leaders now realized that

somehow the Gestapo strongly suspected that he was among them. After a brief

interrogation, Moulin, Dugoujon, Aubrac, Schwartzfeld, and Lacaze were

transferred to the prison of Fort Montluc. But Aubry, Lassagne, and

Larat, who were found upstairs and known to be resistance leaders,

remained and were most severely punished. [2]

"Max is among them!"

Aubry's shoulder was dislocated during one session, and he lost

consciousness three times. And four times, he was subjected to a mock firing

squad in the courtyard of the Montluc Prison. Lacaze later saw Aubry's

chest, shoulders and arms "black and swollen, absolutely swollen." [1]

Lassagne also took heavy punishment because Barbie initially thought he

was Max. Barbie taunted Lassagne, "Your 'Secret Army' is a secret for

nobody, certainly not for us." Meantime, Barbie's colleague entered the

room and threw a bundle of resistance mail onto the desk shouting, in

French, "Max is among them!" When Larat spoke to Dugoujon after being

questioned the first time, he said, "They already know a great deal."

It appears that some time on June 23, Aubry finally yielded under

torture. It was when Aubry began to talk that Barbie identified Max. Aubrac

recalled: "I saw Aubry in the Montluc yard bare to the waist and black

from beating. He told me, 'I've been beaten, I've talked." [8]

Though Barbie always maintained that he never tortured Moulin, those

arrested with him could see Moulin's pitiful condition. In those days,

the doors on the Montluc cells had small holes through painted iron

plates, with no glass or covering discs.

On June 22, Jacques Martel, still seemingly unhurt, was seen in the

courtyeard of the Montluc prison. He approached Dugoujon, who was looking

down at his feet. He told him to lift up his head and added, "I wish

you bon courage." [8]

But by next day, June 23, Moulin must have been identified. Dr.

Dugoujon recalled, "I saw two Gestapo men in civilian dress come to get him.

They took him away little before noon and brought him back that evening,

at nightfall. This was June, so it was late. He had bandage on his

head, he was limping and he was in a poor condition."

On June 24, Aubrac saw him half carried, half dragged by two German

soldiers. "I saw Max's face covered in blood, going off for more

questioning. He was like a collapsed puppet." [8]

That same day at 6:00 p.m., Christian Pineau, the head of

Libération-Nord who had flown back to France from London together with Moulin

in March, also saw Moulin. He was arrested earlier in May and was

allowed to keep his razor, thus becoming the prison barber. He described a

peculiar encounter with Moulin in his book, La Simple

Vérité.

The Last Shave

That night, a German non-comissioned officer told Pineau to follow him

and bring his razor. He led Pineau to the north court, between the

front gate of the prison and the entry to the main building. On a bench a

man was stretched out, immobile.

"Monsieur, you shave," said the officer to Pineau, gesturing at the man

lying on the bench.

Pieanu took a closer look and realized with horror that this wreck of a

man was Moulin. "Max was unconsicous and his eyes were sunken, as if

they had been punched back into his head. He had a ghastly bluish wound

on the temple. Through his swollen lips came a faint rattling breath.

There was no doubt about it, he had been tortured by the Gestapo."

As the Germans urged him to begin, Pineau was struck by the absurdity

of the siatuation. "There I was, my little razor in my hand, in front of

a man who was barely alive and whose face I had to shave." He asked for

some soap and water, which the officer went to obtain. "I was able to

get really close to Max, touch his clothing, his freezing-cold hand, but

he showed no reaction. When the soap and water came, I started,

avoiding the most damaged parts of his face. The blade was blunt from use, but

I managed to shave about his lips and cheeks.

The task perplexed Pineau. "Why this macabre attention to someone who

had been condemned to death? Why take such ridiculous pains after the

horror of torture. This was something inexplicable, having something to

do with the Nazi mentality."

"Suddenly Max openned his eyes and looked at me. I'm sure he recognized

me, but how was he to understand what I was doing there? He murmured,

'Drink'. I turned to the solder, 'Ein wenig Wasser.' He hesitated

for a moment but then took up the mug full of soapy water and rinsed it

out and brought it back full of water. During that time, I bent over

Max and murmured few banal, stupid words of comfort. He uttered five or

six words in English, which I did not understand because his voice was

hoarse and distorted. He took few gulps of water, then lapsed back into

unconsciousness.

Pineau stayed by until 10:00 p.m., apparently forgotten by the officer

who had brought him there. Finally, the German NCO came back and took

Pineau to his cell. "As the NCO climbed the stairs behind me, shaking

his keys, Max lay stretched out on his bench where, undoubtedly, they

would leave him all night. I never saw him again." [11]

He was not left on the bench all night. Dr. Dugoujon noticed the word

'allein' (solitary) on Moulin's cell door. "That Thursday

evening, at twilight, they brought him back in a dreadful condition. He could

no longer walk and he was almost carried by two gaurds, his legs

dragging, his face all disfigured. They lay him on the straw mattress,

leaving the door open, then watched over him all night in case he committed

suicide. Friday morning they cmae to get him again. I never saw him

again." Dr. Dugoujon overheard two Germans talking. "It's really a shame,"

said one. "But he's a dangerous man," said the other. [8]

Pineau was mystifed by the shaving of Moulin, but perhaps there is a

simple explanation. Moulin was was to be transfered to Barbie's superiors

in Paris, so he had to be made as presentable as possible.

Torture or Suicide?

Among the French, there is a somewhat macabre speculation about the

last days of their modern-day hero. Namely, why was Moulin more dead than

alive in a matter of a day or two? (This becomes something of an issue

later as we will see.) It is widely accepted that Moulin was beaten

into a coma by Barbie and his men. But Aubry and Lassagne, who were

severely tortured by Barbie, came out alive from their ordeals. Could Barbie

be so unprofessional as to allow a head injury to the chief of the

French Resistance on the first day of his interrogation?

Later Barbie claimed: "Jean

Moulin, alias Max, displayed magnificent bravery, attempting suicide

several times by throwing himself down the cellar stairs and banging his

head on the wall between interrogations."

Barbie's deputy, Harry Stengritt said likewise: "Moulin's attitude was

far braver. He admitted nothing, on the contrary, he tried every way he

could to kill himself, and we had to protect him against himself."

This time he may be telling the truth. It is plausible that Moulin, who

slashed his own throat to avoid signing a false affidavit, would not

hesitate to make the ultimate sacrifice to save the Resistance. As he

wrote in his last letter to de Gaulle on June 15, "it's the Secret Army

that has to be saved."

However, if Moulin's serious injuries were unintended, why wasn't he

taken to a military hospital? The fact that Moulin was medically

neglected and suffered additional injuries the following days seems to suggest

otherwise.

There is another possibility. With his silence or maybe with a

caricature of his torturer, Moulin might have enraged Barbie to such an extent

that the latter completely lost self-restraint.

Gottlieb Fuch, the Swiss translator at the Gestapo headquarter in Lyon

who claimed that Barbie was enraged by Moulin's caricature of him, gave

the following account in his memoir:

It was 4:00 p.m. and I was on my own in the reception hall.

There was a guard on the main steps next to the porch. I heard a

clatter upstairs and someone was running down the stairs pulling a heavy

object that bounced on the steps. I was facing the stairs directly and saw

Barbie in shirt-sleeves, dragging a man by his feet. when he reached

the hall, he took a breather but kept on one foot on the man. Red-faced

and with his hair flopping over his forehead, he lunged towards the

cellar, dragging the man by a strap tied to his feet. The prisoner's face

was badly bruised and his jacket was in shreds.

When he came up again from the cellar, Barbie strode past with his head

down, his fists clenched, talking wildly. I distinctly heard him bark:

"If he doesn't peg out tonight, I'll finish him off tomorrow in Paris."

Then he climbed the stairs, stamping his feet.

I was on very good terms with the new guard, and I could rely on that

soldier if I wanted to take a look in the cellar . . . I found the

prisoner lying on his belly on the ground, half naked. His jacket had been

taken off and thrown in a corner. His back was lacerated, his chest

seemed caved in. I rolled him over on his side and folded up what was left

of his jacket and put it under his head as a pillow. His eyes were

shut, but he was still breathing. I wiped the blood off his eyebrows, and

he seemed to be coming round. I was caught up in his silence, which was

probably worth more than his life.

The soldier stood next to me, shocked. I knew he supported my gesture;

he kept shaking his head, saying: "All this is going to finish badly."

I am certain he meant for the Germans.

I found out that the man who had been dragged down like some filthy

carcass was a prefect. Next day when I went on duty I discovered that this

same man had been removed from the jail. [8]

Whatever happened, one fact that is undisputed even by Barbie and his

men is that Moulin never revealed any of his encyclopedic knowledge of

the Resistance.

The Urn No. 10137

Gestapo headquarter on 84 Ave. Foch, Paris

Fresnes prison in 1942, where many of resistance men captured in

Paris were held.

On June 25, Aubry, Lassagne, Lacaze, Schwarzfeld, and Dugoujon were put

on a train for Paris and joined General Delestraint in Fresnes prison.

Moulin was in such bad shape that Barbie personally drove him to Paris

maybe on June 28.

Aubry saw Mouin in the Gestapo offices. "Jean Moulin was lying on a

reclining chair, and did not move. He showed no sign of life, seemed to be

in a coma . . . Barbie came in and clicked his heels very loudly in

front of Bömelburg, who stood chain-smoking. Bömelburg told

Barbie in German: 'I hope he comes through this; you'll be lucky if he

does.' They took away Jean Moulin on his sofa-cum-stretcher. Delestraint

and the rest of us tried to comfort him."

Some other time, Lassagne and Delestraint saw Moulin. Lassagne

described the scne, which he though took place between July 10 and 13.

(Moulin's death certificate states July 8, 1943 as the time of death.) "Max was

lying on a divan with his head in bandages; his face was yellow and he

looked dreadful. He could hardly breathe and the only feature showing

any sign of life was his eyes."

Asked by the Germans to identify the man, Lassagne and General

Delestraint detected a warning in Max's eyes, and the general said either

"Monsieur, military honor forbids me to recognize Max in this pitiful shell

of a man" or more likely "How do you expect me to recognize a man in

such a state?" [8]

The Gestapo superiors in Paris were furious at Barbie. Not only he

failed to get any information, Moulin was no longer in any condition to

talk. Apparently, Barbie told them that Moulin took a cyanide capsule for

Aubry said, "They knew that he was Jean Moulin, and he had swallowed a

cyanide capsule. The SS man Misselwitz said so, and he said, 'We'll

save him!'"

Yet like with everythin else about Moulin, accounts are somewhat

contradictory on the exact state of Moulin's health. Perhaps he was further

tortured into comatose state after some time in Fresnes. Jean-Louis

Théobald, who was arrested with Delestraint, was quite near Moulin's

cell at Fresnes Prison. He recalled: "I could communicate with Moulin,

who was on the first floor. He urged me to stick it out and not

succumb, saying we had been betrayed."

He also said, "Delestraint spoke about his talks with Moulin . . . I

don't remember exactly what Moulin said to him, but I remember that

Delestraint and Moulin had the same suspicions." [8]

Also a resistant called Suzette Olivier, who was tortured by having her

fingernails pulled out, said that she may have been confronted with

Moulin at the avenue Foch in the second half of July. His face was

unrecognizable, but she recognized his clothes. This time he was standing,

silent, with a fixed stare, his head bandaged, and looked as though he had

been drugged and incapable of reacting. He kept his hands in his

pockets and he never moved from his position, propped against a door. After

that, Moulin vanished. [2]

Night and Fog

Then on October 19, 1943, the Gestapo sent an envoy to Montpellier to

inform Moulin's family of his death. It was a rare gesture for a

"terrorist" at a time when Nacht und Nebel (night and fog) was the law of

the land, a decree by Adolf Hitler under which "persons endangering

German security" in the German-occupied territories of western Europe were

to be executed or deported without due process or notification to

families. The night and fog decree was issued in response to the increased

activities of the Resistance in France.

Moulin's sister, LAURA MOULIN visited the Gestapo headquarter in the

avenue Foch and met an officer named HEINRICH MEINERS, who told her: "I

have the dossier in my office. I know everything. I conducted the

investigation, but I can tell you nothing." Laure insisted, and Meiners told

her that Moulin had died of a heart attack and his ashes would be made

available later. Meiners added, "Your brother believed he was doing his

duty, but he was working against us. You have my condolences."

On May 2, 1944, another Gestapo officer called at her apartment in

Montpellier to deliver the death certificate. On May 25, a third Gestapo

officer came to say that it would not be possible return the urn and his

personal belongings before the end of hostilities.

Laure Moulin kept her hope that however unlikely, her brother might be

alive after all; somewhere in the "night and fog"; it was only after

the war that she found out what happened to him. [11]

One of the last men to see Moulin alive was Heinrich Meiners. He told

French investigators at a hearing in Germany on December 14, 1946:

In one cell I saw a prisoner who made a bizarre impression

on me. He was lying down, then he sat up and I saw hi walking once in

the room supporting himself on the furnitue and the walls. He was

suffering and he was holding his stomach. He seemed like a very sick man who

did not have long to live. He had a blank, haggard expression in his

eyes. I asked a guard who the prsioner was. He told me he was an

important Frenchman, a former prefect, Jean Moulin.

Berlin, unaware of Moulin's condition, notified the Gestapo in Paris to

send him to Germany. In early July, Moulin was taken to Gare de l'Est

by ambulance and placed in a compartment on the Paris-Berlin train to be

transported to a police hospital in Berlin. But he died shortly before

the train reached Frankfurt. The body was taken out of the train to the

police post inside the Frankfurt station. The police officer on duty

there was by amazing coincidence Johann Meiners, father of Heinrich. In

his report Johann Meiners said, "The corpse was that of someone who has

suffered greatly. It was in a state of complete physical

deterioration." Heinrich Meiners also testified, "The male nurse told me

confidentially that the body was covered with cuts and bruises, and the chief

organs showed internal bruising due to earlier blows, either from coshing or

kicking." [11]

[11]

Even here, there is a curious inconsistency. A German document (a note made

by a German officer investigating the Caluire prisoners) likewise

indicates that Moulin died in Frankfurt. But Moulin's death certificate

stated that he died in Metz. The notice filed by the chief of Metz

police stated that Moulin died of heart attack on July 8, 1943 toward 2

o'clock. The date, too, is uncertain as some resistants claimed to have

seen Moulin later than July 8.

An order was given to cremate the body, as to leave no trace. So his

body was sent back to Paris, where it was cremated on July 9, 1943, at

the Père-Lachaise Cemetery. Information later provided by Ernst

Misselwitz, the German officer in charge of the Caluire dossier in Paris,

indicated that in all probability urn no. 10137 at the

Pè're-Lachaise cemetery in Paris contained Moulin's ashes. It was registered as

"X . . . coming from Germany, July 12, 1943." It was this urn that was

transferred to the Panthéon in 1964. [11]

Aftermath

As for other characters of Caluire tragedy, General Delestraint was

deported to Dachau and was shot by the SS on Aprill 19, 1945, just hours

before the Americans liberated the death camp.

Lassagne was deported to Buchenwald. He survived and returned after the

war, only to die in 1953 as a result of his maltreatment.

Bruno Larat remained in Lyon to be further tortured for information on

parachute drops before being sent to Paris. He died of prolonged

mistreatment in April 1944 in the Dora slave-labor camp.

Emile Schwarzfeld was was deported to Struthof concentration camp,

where he died in June 1944. [2]

They were just some of 56,000 French men and women, who were deported

for resistance or for political reasons. Only half of them returned.

Colonel Lacaze claimed to know nothing about the Resistance (which was

true), and Lassagne swore to that effect. He was released without

charge the following January.

Dugoujon was released likewise after the Gestapo correctly judged that

he was not in the Resistance. After the war, he eventually became the

mayor of Caluire and still owns the historical house.

Aubry talked to the Gestapo in Paris and wrote a 52-page report which

he claimed to contain only information he knew the Germans already had

or which he had invented and knew to be unverifiable. At the end of

1943, Aubry was released having agreed to work for the Gestapo. Instead, he

went underground and rejoined the Resistance in Marseille.

Jean Multon, who started the motion of arrests that led to Caluire, was

shot by the Resistance when France was liberated.

CLAUDE BOUCHINET-SERREULLES, Moulin's much-requested deputy who arrived

only five days before Caluire, found himself to his dismay in charge of

CNR and de Gaulle's delegation. But no one could have replaced Moulin.

He was succeeded by series of interim leaders who were not as effective

in holding the Resistance together. In the aftermath of Caluire, CNR

evolved away from de Gaulle's control and did not realize its potential,

leaving many historians wondering what postwar France would have been

like if Moulin were alive.

As for René Hardy, Raymond Aubrac, and Klaus Barbie, their

subsequent careers were a little more complicated.

BACK < < < Top of

Page > > > NEXT