Jean Moulin Main Page

PREMIER COMBAT

Moulin the Resister

Fall of France

The First Resister

Vichy France

Joseph Jean Mercier

Fall of France

refugees

people waiting in line in front of a bakery

France and Britain, having declared war (Second World War) on September 3, 1939, stood by behind the Maginot line with their overwhelmingly superior forces facing the weakened German line as Germany was slaughtering Poland. Battle of France lasted only seven weeks.

Moulin's posthumously published book, Premier Combat offers a vivid description of this period. As Germans approached Chartres, the largest town in Eure-et-Loire, chaos reigned as refugees overran the town while most of residents joined the exodus southward. Fires burned for days since the entire fire brigade fled. In the hospital, the senior doctor jumped into his car shouting to his patients, "Every man for himself" and a dentist was the only doctor who remained. Meanwhile, the secretary-general of the prefecture, Moulin's No.2 man managed to panic the entire staff "running in every direction like a lunatic, his gas mask flapping on his shoulder." Moulin estimated that there were only 700 citizens left in Chartres out of a population of 23,000, but they were replaced by thousands of refugees. With the police gone, the refugees started to loot the shops and houses. The prefect still managed to keep two bakeries open by shouting down the agitators who were urging a crowd to loot them. [2]

Moulin struggled to maintain order. He posted notices all over the department urging the population to remain calm and stand firm. "People of Eure-et-Loire," his notice read, "Your sons are fighting victoriously against German onslaught. Be worthy of them and stay calm... Don't listen to people who are spreading panic. They are going to be punished... Share my confidence. We are going to win." Moulin himself went round with a bucket of paste and a roll of bills. "I've become a bill-sticker," he said.

Moulin also wrote a letter to his mother and sister right before the Germans entered the city:

"When you receive this, I will, on the orders of the government, have received the Germans and been taken prisoner . . . If the Germans, who are capable of anything, make me say something dishonorable, you will know already that it will not be true." [11]

His words were to be prophetic.

Moulin as the prefect of Eure-et-Loire. His neck is covered to hide the scars from his suicide attempt.

a poster of Moulin's notice to people of Eure-et-Loire

a directive of Moulin at the time of the collapse.

Moulin's dismissal, signed by Marshal Pétain

Moulin's letter to his sister and mother informing them of dismissal

On June 17, 1940, Germans finally entered Chartres to be received by Prefect Moulin in full regalia. He was ready to surrender the city if the German troops respected the civilian population.

But when the Germans came, they committed atrocities against the French colonial troops, and to justify the massacre, they sought to "prove" that Senegalese soldiers commited crimes; predictably, the charges were rape and murder of women and children. The Germans wanted to get a French confirmation for this charade, thus began Moulin's first act of resistance.

The First Resister

Two German officers came to see Moulin that day and told him that their general had an important communication for him. Moulin immediately accompanied them to German headquarters. There instead of a general, a lower-grade officer ordered him to sign a "protocol", an official document attestiing to the "fact" that Senegalese riflemen in a French battalion had committed a horrible massacre in a nearby village, raping and killing women and children.

Moulin said he was convinced that black troops were incapable of such actions, but followed the officer to a house in the Rue du Docteur Maunoury. There, another officer showed him a statement that said, "In their retreat, black troops went along a railroad track near where, 12 kilometers from Chartres, the bodies of mutilated and raped women were found."

"How do you know they were our men?" Moulin asked.

"Because they left some of their equipment behind," the officer said.

"How do you know they committed those crimes?" asked Moulin.

"The victims were examined by German specialists," the officer responded, "the violence they were subjected to offers all characteristics of crimes committed by Negroes." [12]

Moulin's smile, which seemed to say, "Call that proof?," enraged the Germans, and the short blond officer who had come to fetch him said, "Sign, or you'll find out what happens when you mock German officers." Moulin was struck from behind with the barrel of a gun.

The German officers knocked Moulin down and started kicking him. He told them they were a disgrace to their uniforms. The short blond officer worked himself up into a rage and burst out: "You're just a raisonneur de français [French argufier]. You're a nation of degenerates, of Jews and niggers." The tall dark one who had kicked him had a fox terrier beside him, and started whipping Moulin with the dog's leash. "So you want proof," the blond one said. The two officers pushed him into a car and drove him to a hamlet of La Taye.

Then the Germans led him to a large barn in a farm. They heaved open the big double doors saying, "How's that for evidence?" [10]

In Premier Combat, Moulin described the carnage: "He waved his hand at nine bodies lying side by side, swollen, disfigured and shapeless, with torn and stained clothes. You could hardly distinguish their sex, and there were several children among them... The Nazi said: 'That's what your charming niggers have done.' I replied: 'These unlucky people have been hit by shells...'"

They shoved the prefect towards a corner where the limbless trunk of a woman lay on a table. A German gave Moulin another push towards the body, and the door was closed.

Moulin wrote: "I was projected onto human debris. It was cold and sticky, and my own bones turned to ice. In this dark corner, overcome by the nauseous odor from the bodies, I shivered feverishly."

The Germans finally opened the door and came in with the affidavit. They tied his wrists with a dog leash. For hours, Moulin was brutalized and badly beaten for refusing to sign the protocol. Late that night, the Germans led him to a cell, jeering: "Since you love niggers, we've given you one to sleep with." As Moulin stumbled forward into the cell, he saw a Senegalese soldier, crouched in the corner. He too had been beaten by the Germans. [12]

Moulin wrote: "I realize I am now at the limits of my endurance, and if they start again tomorrow, I will end up by signing. It was a terrible choice: to sign or die." He concluded that to sign would be to dishonor both the French army and himself.

Moulin looked around and saw that the floor was covered with shards of glass from windowpanes. He "knew at once what these fragments could do. They could cut a throat as easily as a knife could."

A few hours later a German guard, making his rounds, found Moulin in a pool of blood. The Germans were forced to take him to the hospital. A German officer told a nun in charge of the hospital: "You didn't know, did you, Sister, that your prefect had special tastes. He wanted to spend the night with a negro, and look what's happened to him." But they could not prevent hospital attendants from learning the truth and spreading it through the village. In those dark days of humiliation and sorrow, Mouin became a local hero. [12]

Incidently, on this very same day of June 18, 1940, CHARLES DE GAULLE made his historic speech from BBC studio in London, in which he called the French outside France not to surrender but carry on the fight. He finished with the words, "The flame of French resistance will not be extinguished." The Resistance was born.

Vichy France

Moulin remained the prefect of Chartres for four months until he was dismissed on November 2, 1940. It is interesting to note that his dismissal was brought on by Vichy government rather than the German authorities.

Colonl F. K. von Gütlingen, the new Feldkommandant was embarrased by the treatment Moulin suffered and determined to establish correct relations between the Wehrmacht (German army) and the people of Eure-et-Loire. The public services were restored with German help, and Moulin looked after needs of the population. He won admiration from Colonel Gütlingen, who wrote to him in farewell: "I wanted you to know how very agreeable our life together in your house has been for me. I have respected you as a Frenchman and you have respected me as a German officer."

Major Ebmeir, who replaced Colonel Gütlingen, objected to dismissal and asked his superiors to refuse to let Moulin go. He made a speech saying "I congratulate you on the energy with which you have defended your people's interests and your country's honor." [2]

France after the armistice - Occupied France and Vichy France

Marshal Pétain and the French exchange Nazi salutes

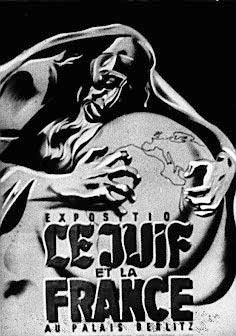

a poster advertising an "exhibition" on the Jews in France

René Bosquet, chief of police, with Richard Heydrich

But it was the French government that found Moulin intolerable.

Before the armistice, prime minister Paul Reynaud wanted to continue the war aginst Germany from North Africa, but majority of his cabinet accepted the defeat. On June 16, 1940, 569 of France's 649 deputies and senators voted in favor of bestowing supreme power to Marshal HENRI-PHILIPPE PÉTAIN. Thus the Third Republic voted itself out of existence and ushered in the period of Vichy France (named after the spa town where this government was established). Like the Germans who voted Paul von Hindenburg in 1925, the French entrusted the fate of their nation to the 84-years old victor of Verdun, a hero of the First World War.

On June 17, the Marshal addressed the nation. "I offer to France the gift of my person that I may ease her sorrow," he said, "It is with a heavy heart that I tell you that we must halt the combat. Last night I asked the adversary whether he is rady to seek with us, in honor, some way to put an end to the hostilities." [3]

Travail, famille, patrie

Despite de Gaulle's myth of France as the nation of valorous Resistance fighters, the truth of matter is that the French people almost unanimously supported Marshal Pétain and his collaborationist Vichy regime at least in the early stages.

Marshal Pétain put a benevolent face on the Vichy regime, but it was founded on the fascist idealogy of Action Française. Pétain's National Revolution envisioned the restoration of old France where the values of work, church, and family would once more prevail. It was no time for democracy. The republican motto of "Liberté, égalité, fraternité"(Liberty, equality, fraternity) was replaced by the new slogan of "Travail, famille, patrie"(work, family, fatherland).

Under Vichy regime, the French leaders who had embarked to Africa to continue the fight were arrested on arrival and tried as tratiors. The soldiers outside France were ordered to stop the hostility and return to France. De Gaulle, who appealed the French to continue ro resist, was sentenced to death in absentia. The Jews and foreigners were to be hated as those resposible for the decline of the French might and eventual defeat.

Most shameful of all, anti-Jewish laws of Vichy went into effect almost immediately. As early as July 22, 1940, just a month after his government was created, Pétain established a commission to revise the naturalization of the Jews. On October 3, the French equivalent of the Nuremburg laws came into effect. They were more stringent in their definition of who was and was not a Jew than their Nazi counterpart. Jews were excluded from the public service and from many of the professions. Most of all, these Vichy laws established the notion of a Jewish race, whereas the German authorities had been careful to refer only to the Jewish religion for fear of offending French public opinion. On October 4, a law permitted the authorities to intern foreign Jews in special camps.

During the peak of collaboration in 1942, when Vichy and French police fully cooperated with the Nazis, 3,000 Jews were transferred from Drancy to Auschwitz every week. By the time the war ended, nearly 76,000 people had been deported. Of these, 3,000 survived. [3]

Moulin, while remaining a prefect, followed an obstructionist route in enforcing these new policies. Nobody was interned, and he intervened for Jewish teachers and doctors, who were targeted by these laws. However, it seems that it was when he was finally dismissed for "continuing to apply the policies of the Popular Front" that Moulin was confronted with the ultimate choice: to join the majority of French men who accepted Vichy government and waited for better times, or to resist.

Joseph Jean Mercier

After dismissal, Moulin went back to his family in St. Andiol and settled down in early retirement in all apperances. In fact, he was preparing to escape France for London or America to join in the anti-Nazi activities. During the nine months that took to get an exit visa, he began quietly to feel out burgeoning resistant movements. While he was still a prefect, Moulin issued himself a bogus identity card in the name of Joseph-Jean Mercier, born at Péronne, a town whose regristry records were destroyed during First World War. Under his real identity, he established a cover as an art dealer, which would explain all those frequent travels he was undertaking. He also wrote a rough draft of Premier Combat in the winter of 1940-41.

On December 7, 1940, Moulin asked a trusted former deputy of his in Toulouse to issue an exit permit. But this official, loyal to new Vichy regime, not only refused it but reported to the prefect of Toulouse, and the warning of Moulin's plan to leave the country was circulated to the Vichy border police. This police report made no mention of Moulin's new identity, which he had been too wary to tell his former deputy. [2]

Henri Frenay

While he was still looking for an exit permit, Moulin met HENRY FRENAY, the founder of the most important non-communist resistant group, Combat in April or August 1941. Frenay described the meeting in his book, The Night Will End:

Though [Moulin's] opposition to the Vichy regime was total, he spoke of it not with hate but with contempt. Nazism horrified him. He planned to leave France with the sole aim of joining General de Gaulle, who, he claimed, sorely needed men.

"However," he continued, "I'd like to be able to supply him with as much information as possible about France. So far I've met many opponents of the regime, but no one who was actually involved in the Resistance. That's why I was so eager to see you, because I've been told that if anyone is in a position to help me out you are."

We talked together for several hours without a single interruption. I began with the [Combat], whose history I sketched beginning with its birth in this same city of Marseilles just one year earlier.

. . .

[Moulin said,] "I intend to depart as soon as I can. If all goes well, I shall arrive in England toward the end of the summer. I shall faithfully deliver your proposals - that I promise you. I belive that you are right in your wish to consolidate our scarce manpower, so I shall have no trouble in being your advocate."

I was satisfied with our interview but skeptical of the returns it might bring. At times I had the feeling of having set adrift a message in a bottle. Yet, in a deeper way, I believe that I had found a faithful messenger. My impression of Moulin was really excellent. He was calm but reacted passionately to certain topics. He was his own master. I liked the expression in his eyes, and my experience told me that a man's look hardly ever plays false.

. . .

It was almost seven o'clock when Jean Moulin left. I opened the blinds and watched him disappear in the direction of the prefect's office. I sighed. It was one more contact among many, and so many had already proved fruitless!

I had no intimation that this day had been of capital importance to the French Resistance and its relationship with London. [7]

Report on Resistance

Professor Joseph Jean Mercier, who supposedly taught law at Columbia University (or New York University according to another account), crossed into Portugal on September 12, 1941. Once in Lisbon, Moulin immediately contacted the British and American embassies, but his trip to London was to take more than a month.

One of the reasons for this was that the British were suspicous of all travelers, even those with the best-looking credentials. Many Nazi spies, drawn from the conquered nations, had infiltrated into British services posing as anti-Nazi refugees. [4]

Hoping to expediate his trip to London, Moulin wrote a long report on the objectives and needs of the resistance movements he had contacted in France. After describing at length the status and activities of three major movements, he argued:

It would be mad and criminal not to make use of these soldiers, who are prepared to make the greatest sacrifices, in the event of any widescale operations by the Allies on the Continent; scattered and anarchical as they are today, these troops can tomorrow constitute an organized army of 'parachutists' on the spot, knowing the country, having singled out their opponents and decided on their objectives.

If no organization imposes upon them some sort of discipline, some orders, some plan of action, if no organization provides them with arms, two things will happen:

On the one hands, we shall witness isolated activities, born to certain failures, which will definitely go against the common goal because they will take place at the wrong moment, in a disorganized and inefficacious manner and thereby discourage the rest of the population.

On the other hand, we shall be driving into the arms of the communists thousands of Frenchmen who are burning with the desire to serve - and this process will be helped all the more since the Germans themselves are the chief recruiting agents of the communists, citing as 'communist' all demonstrations of resistance on the part of the French people [5].

Such was Moulin's concern of the French Resistance being co-opted by the communists.

Moulin not only provided most detailed information about resistance movements to reach London so far, he also proposed a srategy to exploit it, arguing it could make a military contribution to the war (besides intelligence and propaganda works). For Moulin, it was imperative that the British or de Gaulle to create a direct form of communication with with resistant movements.

Not surprisingly, the British services were impressed. Moulin was in England by October 20.

De Gaulle vs. SOE

General de Gaulle later wrote in his memoirs, "In October 1941 I learned of the presence in Lisbon of Moulin, who had arrived from France and was seeking to come to London. I knew who he was." De Gaulle wrote to ANTHONY EDEN, Churchill's liaison officer for all exiled groups in London, asking him to send Moulin to him as soon as he arrived in London. But he had to wait for two months to see him. Eden, alerted by his own services that this was a valuable man and a potential British agent for France, had no intention of turning Moulin over to de Gaulle. The British recognized Moulin as the the first figure of any consequence to come out of France since 1940. [9]

The British service that was in charge of coordinating subversive and sabotage activity in the German-occupied countries was called Special Operations Executive (SOE), set up in July 1940. Captain Eric Piquet-Wicks, acting head of the RF Section of SOE recalled that Moulin had, "sparkling eyes, a lively manner ... grace of the movement and almost absurdly youthful appearance ... Above all he had charm: simply to be in his presence was a delight." The SOE note read: "He is the first person I have met or heard of having . . . the sort of natural authority and experience which his past history gives him." Another SOE agent said, "His patriotism shone out of him, his personality compelled you to notice and to admire him." [2]

Moulin was astonished to find the British overwhelming him with kindness and flattery and keeping him tied up in meeting and interrogations about what was happening in France. They never quite refused him to let him see de Gaulle, but kept him so busy with a guided tour of British services and offer of top jobs. MAURICE BUCKMASTER the head of F section of SOE (the independent section operating in France) talked with Moulin but could not overcome his objection. Moulin wanted to speak to de Gaulle before deciding. [4]

BACK < < < Top of

Page > > > NEXT