|

|

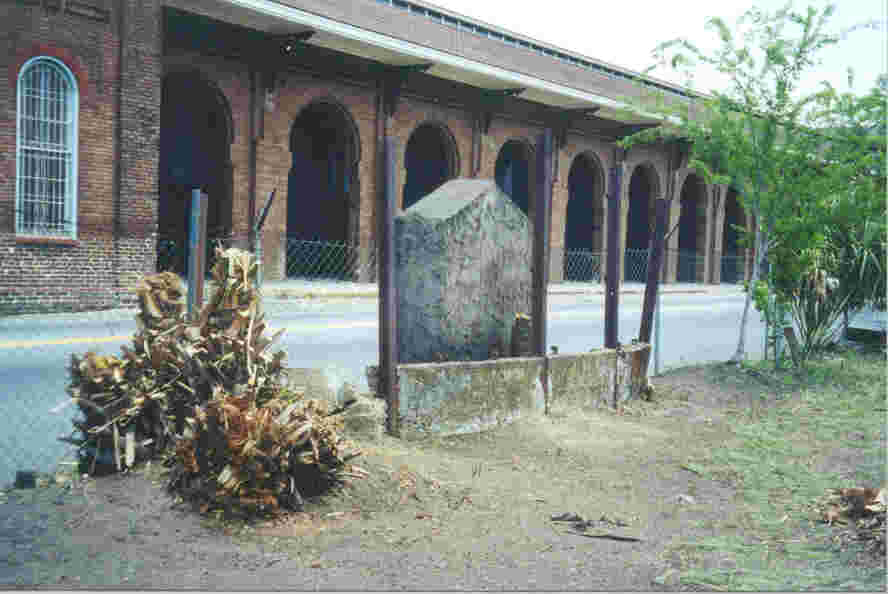

Siege of Savannah

Marker Commemorating

The Siege of Savannah

This neglected and forgotten marker

sits on Louisville Road, just a few yards from MLK Blvd.

Across the street from the Savannah Visitors Center.

Bonaventure Chapter of the National Society of the Daughters

of the American Revolution has been granted a

"Beautification" lease by the Central of Georgia Railroad,

present owners of the property, in order that we might make

the marker more "Presentable". Beginning 22 May, 1999 and

continuing as the need persist and authorization to the

property remains we will work toward making the marker a

more fitting memorial to the Siege of Savannah and the many

men who died there.

Photo by Faye Dyess

Cleared, but not yet

presentable...

Photo by Faye Dyess

The first step in reclaiming the

marker is almost complete. The marker can now be seen.

Thanks are due to several of our members, their HODARS, and

Mr. William Hodges, HODAR of Frankie E. Hodges, and his

group of Sea Cadets. Mr. John Archer, HODAR of Lynn M.

Archer, spent the entire day chopping and sawing. Thanks to

everyone who helped.

Photo from Savannah Morning News

The Battle of

the Siege of Savannah

The Siege of Savannah occurred 9

October 1779. The site of this battle should be a honored

site. This battle was the second bloodiest battle of the

Revolution. More men died in battle only at Bunker Hill. The

hundreds that died there were buried in a mass grave at the

site. This battle marked the first time American and French

forces fought side by side. Two of the fallen heroes of this

battle are Sgt. William Jasper and Count Casimir

Pulaski.

Siege de

Savannah

"For fifty-five minutes in the early

dawn of October 9, 1779, there was fought on the then

western outskirts of Savannah what was unquestionably the

most sanguinary battle of the entire eight years of the

American War for independence...fought with a partly lifted

fog obscuring and hindering the movements of French and

American and helping to continue the confusion. In a single

hour there fell within an area of a few hundred square yards

more dead and wounded than are credited to any other

battlefield in the struggle for American independence.

(Thomas Gamble, Savannah Morning News, September 1,

1929)"

"This October 9th battle was fought on the present site

of the Savannah Visitor's Center at Martin L. King and

Liberty Streets; in 1779 it was called Spring Hill.

Vice-Admiral Charles-Henri d'Estaing had sailed from San

Domingo in the West Indies in August; his French troops had

been disembarked in September at Beaulieu Plantation on the

Vernon River, fourteen miles south of Savannah, and at

Bonaventure and Greenwich Plantations on St. Augustine Creek

near Thunderbolt, three and one-half miles east of Savannah.

When the invading French, who had been joined by American

militia, formed a half-circle around the British Savannah on

September 15, the French-American forces numbered about

5500. Within the city, the British forces were approximately

2630 of which 200 were armed Negros and 80 Creek and

Cherokee Indians. When the battle ended at Spring Hill that

October 9th morning, 333 British, French and American

soldiers and 32 officers were dead; 377 lay wounded. The

British had lost only three officers and fifteen soldiers.

The dead were buried in a mass grave probably on the site of

the present Savannah visitor's Center.

Bonaventure Plantation had been a captive of the

invading French since early September. Many of d'Estaing's

troops had come ashore suffering from scurvy and a stormy

crossing from San Domingo; rain and chilly weather had

caused fever to become common among the troops after they

landed. Two hundred soldiers and twelve officers were

hospitalized at Bonaventure Plantation unable to complete

the three and one-half mile trek to Savannah. Even before

the sounds of the French-American cannons reached

Bonaventure on September 20th, the women at the plantation

saw their home victimized by war.

Claudia Mullryne, her daughter Mary, and Mary's

children-John Mullryne, Josiah, and Claudia-were alone at

Bonaventure except for the plantation slaves. Colonel John

Mullryne, who had publicly declared his British allegiance

by oath in September, 1775, had left the plantation and gone

to Savannah as soon as the French arrived off Tybee

Island. Josiah Tattnall, Mary Mullryne's husband, had also

vowed his allegiance in 1775; he was in command of British

troops in Savannah. The Tattnalls had suffered an early loss

from the invasion; Fair Lawn, their two-storied dwelling in

Savannah, had been burned with all its outbuildings. In

fortifying the city, it was feared Fair Lawn would prove

advantageous to the advancing French-American forces.

Claudia and Mary waited; surrounded by French who knew the

Mullryne-Tattnall loyalty to King George III. The French

also knew that being loyal British subjects, the women had

inherited from the British Nation a prejudice against any

person of French descent. Claudia, Mary, and the Tattnall

children listened as the French cannons thundered at

Savannah from October 3rd through October 8th. Despite their

desecrated condition, they were more fortunate than the

women and children within the city; Count d'Estaing had

denied the British permission to evacuate anyone before or

during the six days the one thousand shells fell into the

besieged city.

After the October 9th battle, Count d'Estaing, wounded in

his arm and in the calf of his left leg, rode on horseback

to Greenwich Plantation. On October 7th, Jane Bowen, widow

of Samuel Bowen who built Greenwich, had written d'Estaing

informing him of her cooperation and requesting that she and

her fourteen year old daughter Elizabeth Ann be spared the

ravages that were imposed upon Bonaventure. Until October

9th, Greenwich had been headquarters for the French

officers, but 377 French and American wounded had to be

accommodated. This made it necessary to use Greenwich

despite Jane Bowen's protest.

The movement of the wounded from Spring Hill to Bonaventure

and Greenwich occurred without retaliation from the British.

In fact, the British loaned two carriages to convey the

wounded. many of these men probably never left the

hospitals; they lie in unknown graves on the grounds that

are Bonaventure and Greenwich Cemeteries.

The withdrawal of French troops began October 13th under the

direction of d'Estaing. The primary site of departure was

Causton's Bluff, north of Greenwich. County d'Estaing

commented that the troops returned aboard the vessels not

only without leaving anything behind, but more than that,

without being attacked, annoyed, or even followed. The

British seemed content enough that the French were

leaving.

In a letter dated October 17th, Governor James Wright

reported that the volunteer Chasseurs, a brigade of 545

Black and Mullato troops of San Domingo, had departed from

Bonaventure. The French withdrawal was not completed until

October 21st, and even then not all the French were aboard

the departing ships. Contrary to d'Estaing's statement

"without leaving anything behind", in addition to the men

who had deserted during the 24 preceding days, there were

also those who simply got lost in confusion of

departure.

The Mullrynes and Tattnalls survived this encounter with the

American revolt to free Savannah from the British.

Bonaventure, though damaged and pillaged, was repaired, the

terraced gardens refurbished, but the graves of the unknown

French soldiers were a constant reminder of the accelerating

political turmoil. By the summer of 1782, the Mullrynes and

Tattnalls were forced to leave Bonaventure as the tide of

Americanism swept them out of the colony; the Mullrynes to

New Providence, Nassau, in the Bahamas; the Tattnalls to

London, England.

Ironically, Count d'Estaing fell victim to the political

revolution in his own France. Called as a character witness

for Marie Antoinette during the French Revolution, he was

condemned to death and beheaded on April 28, 1782. The

sixty-four year old nobleman is supposed to have remarked

when the sentence was pronounced, "When you cut off my head,

send it to the English; they will pay you well for it!"

This quotation was

taken from "Friends of Bonaventure, Commemorative

Issue-October 1779, October 13, 1996" by Mr. Terry Shaw,

Chairman, and used with his permission.

Chapter Regent Faye Dyess

and Secretary Dory Hickson of Bonaventure Chapter, NSDAR, at

the 2003 commemoration of the Siege of Savannah.

(photo

by Lynn Wright)

© 1998

|