The History of the Personal Computer, Part II

In our last exciting episode we examined the development of personal computers up to the advent of the Apple. We will now fill in this history a bit, as well as the transition between Apple (and other "proprietary" home computers, like those made by Commodore and Atari) and IBM.

Jobs met Wozniak when Jobs was about 14 and Wozniak was 18. In spite of the age difference, they became friends, a few years later, business partners--they began making devices called "blue boxes" that exploited bugs in the telephone system and allowed a person to make free long-distance phone calls. It appears that Jobs was the "idea man" and promoter, while Wozniak was the engineer. After both flunked out of college, this pattern continued; Jobs talked his way into a job at Atari, but Woz (by then an HP engineer) did most of the real circuit design.

|

|

A picture of Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak together, probably around 1976. |

In 1975, the real breakthrough occurred. Woz took Jobs to a meeting of the Homebrew Computer Club, where one of the dreaded Altair 8800 computers was displayed. While Woz was in love with the technology, Jobs noticed the burning passion of the members for computers, and saw opportunity.

Their first computer, the Apple I, was introduced in kit form in the summer of 1976; somewhere between 40 and 200 units were sold at a price of around $500 to $670; this probably made them more money than Woz's annual salary. Jobs immediately swung into gear: he had a logo designed (the familiar Apple symbol), found another engineer to finish and polish Woz's new design for the Apple II, and managed to get venture capital to manufacture the new machine. Jobs also cleverly made sure that the new machine had a nice-looking case. Thus, in only a year, the Apple had gone from hand-wired kits to fully-assembled units. The Apple II series, initially released in 1977, would sell over a million units over the next ten years, and would change to face of the personal computing.

|

|

Apple II, with monitor and two accessory disk drives. Source: http://apple2history.org/history/ah04.html |

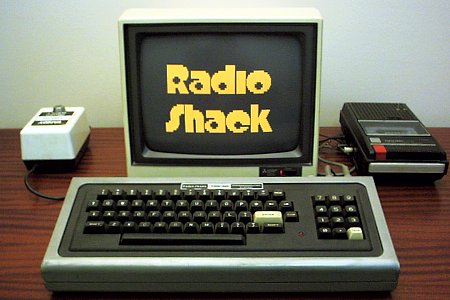

However, there is one more twist to this story. The original Apple II may have been cleverly designed and nice-looking, but it also had several short-comings. It could only type in ALL CAPITAL LETTERS, so it really wasn't good very good for typing formal business letters; only in 1983, with the Apple IIe, did lower case letters become available. Hobbyists liked the machine, but that was a limited market that numbered in the thousands, not hundreds of thousands. So… who bought all of these early Apple computers? The answer: business people. The Apple II shipped with 4 only kilobytes of standard memory, but up to 48 kilobytes could be added quite easily. At this time (1977) most other machines in its class (mainly Radio Shack's popular but much criticized TRS-80, known by users and critics alike as the "Trash 80") could use not more than 8 to 16 kilobytes.

|

|

Radio Shack TRS-80, model 1. Note the cassette tapedeck for loading and saving programs! Source: |

As a result, one of the first applications available to for the Apple was VisiCalc ("Visible Calculator"). What, you might ask, was so special about this program? Answer: it was the first spreadsheet program, and at first it was only available (for $250) for the Apple. Accountants, bankers, and financial analysts could use VisiCalc to do in an hour the same work that it took them a week to do with an adding machine. These people were quite willing buy the computer, just for this one program. Indeed, VisiCalc was the first "killer app" (short for "killer application program"). One definition of killer app might therefore be: program so incredibly useful, that people will buy a computer just so that they can use this one program.

The Apple II's nearly unintentional success in the business market helped in inspire a number of other companies to place personal computers on the market. It is possible that you could remember some of these: The Atari 400 and 800 (1979), the Texas Instruments TI-99/4 and TI-99/4A (1979-1980), the Sinclair ZX-80 and ZX-81 (1980-1981), the Commodore VIC-20 (1981) and Commodore 64 (1982) all entered the market over the next few years. Most of these machines attempted to undercut Apple on price; an entry-level Apple II cost almost $1000, and with accessories added (disk drives, more memory, etc.) the price could easily run up to $2000 to $3000. A Commodore VIC-20, on the other hand, could be had for $300 when it was first introduced, and the Sinclair ZX-81 was only $100.

|

|

Commodore VIC-20 (left) and Sinclair ZX81 (right). The ZX-81 was quite small; compare it to the size of the accessory cassette tape recorder. Source: http://www.kekatos.com/ |

|

With the exception of Radio Shack, which offered a variety of computer models and lines, most of the computer companies appear to have targeted their machines for specific markets: Atari generally did very well with "gamers," while Apple successfully expanded into the educational market. Commodore seems to have appealed to middle-class families, with the Sinclair appealing to people wanting to dip their toe into the new personal computer craze, but not spend much money doing so. This diversity actually seemed to work; over half a million ZX-81's were sold, with the Commodore 64 doing even better at 17 million units! However, one drawback united all of these machines: generally speaking, machines from one company could not use programs from the other, at least not without additional (generally expensive) hardware, if the conversion hardware was available at all. In fact, many times this was true even within companies. For example, programs for the Commodore 64 would not necessarily run on the VIC-20, and there were also problems moving programs between some of the different models of TRS-80's. The result was a highly fragmented market.

A dramatic change was about to occur, however. This was IBM's entry into the PC marketplace.

IBM had actually attempted to enter the "low end" computer market before, during the mid-1970's. However, it had failed because their idea of "low end" was about $20,000. It also did not inspire their sales staff, who were paid on commission---why try to sell a $20,000 computer when you could make more by selling machines that cost $200,000? Even worse, there was no software for the machine. However, the leaders of IBM--especially their president, Frank Cary--were not stupid; they saw that Apples (with VisiCalc) were doing very well. The question was how to enter the market.

|

|

The IBM 5100 of 1975. While sort of a PC, it cost around $20,000 and rapidly failed in the marketplace! Source: http://www.cedmagic.com/history/ibm-pc-5100.html |

The first idea was for a true IBM personal computer was for IBM to partner with Atari; they would buy Atari parts and repackage them in IBM cases. The machines would have the advantage of having a pool of Atari programming talent to draw upon. Cary wanted a PC, but it wanted an "all IBM" machine, so the idea was rejected. The second idea Cary liked better: improve on the old Altair design. This meant looking around to see what chips, software, connectors, and hardware were available on the open market, then figure out the best way to assemble them into a serviceable computer. Sales would be done in two ways: the regular IBM sales force would sell large lots of computers to large businesses, thus yielding enough in the way of commissions to keep the sales staff interested in pushing the new machines. However, the machine would also be made available through department stores, which was a departure from the way IBM usually worked. The only really unique part about the entire computer would be a single chip on the main circuit board called the ROM-BIOS ("Read Only Memory-Basic Input Output System"). This chip basically comes into play when you first turn on your computer in the morning; it is a small but essential "wake-up-and-load-your-operating-system" program that tells the computer basic information, such as how to access its memory, disk drives, and add-in cards.

Only two questions were left to solve. What operating system ("OS") would the computer run? And where would the computer programs and languages come from?

The answer to this at first appeared obvious: use an operating system named CP/M. As you may recall, the early Altair 8800 could be programmed by flipping switches on its front panel, entering rows of 1's and 0's. Obviously, this was a drag! A computer programmer named Gary Kildall wrote a program that would allow a person to access the computer in a more convenient fashion from a "command line," which looked a lot like this:

A> TYPE WS.HLP

A person could thus "talk" to the machine by typing on a keyboard, using commands that looked sort of like English words; in the example above, the computer would show on its monitor ("TYPE") the "help" file for WordStar, an early word processing program. This was MUCH easier than entering binary numbers on the front panel!

Kildall had written an operating system that had worked on the Altair/IMSAI computers, and had found that with a little work he could make versions that would run on most of the other popular personal computers of the time. This, in turn, would allow serious computer programmers to use standard versions of computer languages (such as BASIC, Fortran, Pascal, and COBOL) to write applications for end users. Kildall wrote versions of CP/M that would run on most common PCs of the day, with the exception of the Apple. Kildall sold his OS for $279, one per set of disks.

Click here to learn more about CP/M. You can also log on and try a real CP/M machine, too!

IBM thus made a trip to visit Bill Gates to discuss development of a version of BASIC that would work on their new PC. (Gate's version of BASIC for the Altair had been well-received. Even better, his Altair BASIC contained its own elementary operating system, so it could run on a machine with no OS installed.) IBM then went to visit Kildall at his small company, Intergalactic Digital Research. There problems began. IBM wanted to meet with Kildall in absolute secrecy, which Kildall and his wife (and business partner) disliked. Finally, when the meeting did take place, Kildall revealed that he was in fact working on a version of CP/M that would work on IBM's new product. However, he refused to give IBM any special preference, as he knew that other companies would also be interested in his OS. Also, Kildall was not in a huge hurry to market the new version of his operating system; the current versions were bringing in about $6 million dollars per year on then-current (Z-80 and 8080 based) hardware, even without signing a secretive, complicated contract with IBM for use with the new, untried 8088-based system.

The IBM representatives left frustrated; they needed an operating system and they needed it soon in order to meet their shipping date. Returning to Bill Gates, they asked if he could help them.

|

|

Bill Gates (right) and Paul Allen in 1981, soon after they signed the deal with IBM. |

Indeed Gates could. It turned out that a friend of his, Tim Paterson, owned a small computer company, Seattle Computer, and had been working on a CP/M clone called "QDOS" (for "Quick and Dirty Operating System") as a side project. Ironically, QDOS was written so that Seattle Computer could demonstrate its computer products on new computers running Kildall's planned new version of CP/M, but Kildall's project (called CP/M 86, because it ran on Intel's then-new 8086 and 8088 chips) was late shipping.

Anyway, Gates and his company Microsoft first leased and then bought the rights to QDOS for roughly $50,000. They cleaned up the program a bit, then turned around and sold it and IBM-compatible versions of BASIC, Fortran, Pascal, and COBOL to IBM for $1 million. While this deal was certainly shrewd, it was not dishonest--the programming languages were necessary for other programmers to develop applications for the IBM. The true brilliance of the deal was that Microsoft got to keep some rights to DOS and sell it to other companies; IBM--with some reason--thought that the programs and the computer were the money-makers, not the operating system. An operating system with no applications to run on it is, after all, only good for a few hobbyists.

As a result of this deal, DOS was bundled with IBM's personal computer when it shipped. Kildall did eventually finish CP/M 86, which ran on the IBM…but it appeared a year after IBM had begun marketing their PC. Even worse, Kildall charged $279 per set of disks. Not surprisingly, it was not a big hit, even though some felt that CP/M 86 was a superior product. Eventually the price was lowered and the product renamed DR-DOS, which stands for "Digital Research DOS." While this DOS competitor eventually faded away, it continues to be used by some hobbyists and certain specialized commercial computer applications.

IBM officially launched their computer, the IBM PC, in August of 1981. The base unit, featuring a 4.77 MHz Intel 8088 chip, 64 kilobytes of RAM, DOS 1.0, a single floppy drive and no hard drive, sold for just under $3000. Most used a black and white (or black and green, or black and amber) screen. However, if one purchased several hundred to several thousand dollars of upgrades (more RAM and a second floppy disk and/or a hard drive), the machine actually became useful. And, even though DOS could not usually run a CP/M program, the two operating systems were similar enough that software companies could usually rewrite their software to run on the IBM quite easily. Within a year or so, the IBM PC had a word processor (WordStar, rewritten from the CP/M version in a single night!), a database program (dBase, also ported from CP/M), Peachtree accounting software, and of course a spreadsheet (VisiCalc, ported to the IBM PC platform).

However, even with IBM in back of it, the other PC makers (Radio Shack, Atari, Commodore, Apple, and others) continued the thrive, at least for a time. While the IBM PC did well, selling 200,000 the first year, the Commodore VIC-20 and Radio Shack units sold at least as well. The IBM machine was obviously aimed at the business market; the machine was expensive and bulky, programs ran slowly, graphics were poor, and non-business program offerings (such as games) were quite limited. However, they could offer excellent sales and service, especially for businesses. The machine was also designed so that accessories (add-in cards, printers, memory, etc.) could be installed easily, and soon others were manufacturing parts and accessories to extend the original limited capabilities. And, to its credit, for several years IBM led the way in improving the unit: Within two years they had announced the IBM PC-XT which, for about $5000, included a floppy drive, 128 kilobytes of RAM, and best of all a 10 megabyte hard drive. There was also the much more limited "PC Jr." for about $1000, but it sold poorly.

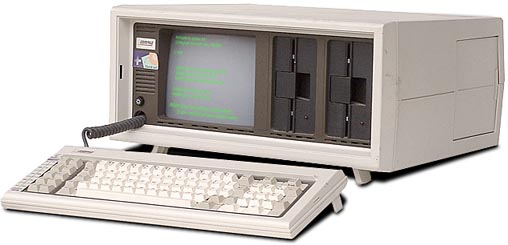

Oddly, IBM had trouble making much money from its PC's, even though it sold millions of them and for several years it commanded the business market. Part of the problem seems to have been that they had a good reputation, but their computers were too expensive for most home and many small business users. Their machines were also conservative in design, especially considering that they were built using parts readily available on the open market. This situation created an opportunity for others to enter the field. Soon Compaq figured out how to legally copy (more precisely "reverse engineer"--figuring out exactly what something does, then making something else that does the exactly the same thing, but in a different way) and produce the only thing really unique about the IBM--its ROM-BIOS chip. In 1983--only two years after the IBM PC had been introduced!--they began marketing the first "PC clone." This PC could run any program that the IBM did, and was also somewhat cheaper. Even better, the whole thing was at least somewhat portable. The whole thing, screen and all, weighed a little under 30 pounds, making it "luggable."

|

|

The Compaq Portable, the first IBM clone. This well-designed computer was very successful and put Compaq on the map. (For more information, see http://oldcomputers.net/compaqi.html) |

This overall trend---IBM paving the way, pursued by competitors who copied and sometimes slightly improved their equipment---persisted until 1987, when IBM made several major, but in retrospect understandable, blunders. First, they were slow to market a PC based on Intel's then-latest-and-greatest chip, the 80386. As a result, Compaq raised eyebrows by marketing a 386-based machine first, making the company look more like an innovator than a copier for the first time.

Secondly, when IBM did finally introduce its new line, the PS/2 series, it included a low end unit based on the 8088 chip, a couple of midrange units based on the 80286 chip, and a high-end unit based on the 80386 chip. There were two problems here: first, nobody wanted the low-end unit, because the chip was so outdated and lacked capability. Second, out of frustration with being copied, IBM introduced its own internal PC architecture (called "Microchannel Architecture," or MCA) so that people would have to purchase only IBM-licensed parts and add-in cards. While these cards actually worked very well, a purchaser could only use them in IBM machines, and the price was quite high. As a result, MCA was not a commercial success and the clone-makers pulled ahead in the market.

Thirdly, IBM tried to leave DOS behind and introduce its own operating system called OS/2. First introduced in 1987, IBM spent years and millions of dollars trying to make it go "mainstream." Like microchannel architecture, OS/2 had some excellent technical points. However, it was too slow, expensive, and cumbersome for most users. Later on, Microsoft would also discourage other software companies from writing programs for it. OS/2 remains a niche market to this day. Microsoft, on the other hand, was working to build upon, rather than replace, DOS with its Windows program.

As a result of these three errors (slow production of 386 machines, MCA, and OS/2), IBM spent millions of dollars and a great deal of time developing products that few people purchased. As a result, IBM lost its lead in the very market that it created. Compaq takes the lead in a market filled with clone-makers--only to be displaced within 10 years by Dell, who finally figures out how to market effectively to both home and corporate users! Indeed, if the "IBM clone" market had not been so diverse, supported by a number of different companies (Compaq, Hewlett-Packard, and other "big names," plus countless "mom-and-pop" small computer shops), IBM might have derailed the IBM-compatible PC market.

Others did not have so much infrastructure and were thus not so lucky. Apple, for example, also made a number of serious mistakes. From about 1980 to 1983 Apple neglected development of the popular and profitable Apple II line for the disastrous Apple III and Lisa machines. (For more about the Lisa, click here!)

|

|

The Apple Lisa, the first commercially-sold computer with a graphical user interface. While capable, the machine was slow, overpriced (about $10,000), and had little software available for it. It took four years and $50 million to develop...then sold less than 100,000 units total. It was marketed from 1983 to 1985. In 1989 Apple ended up dumping thousands into a landfill. Picture source: www.macgeek.org/museum/applelisa1/ |

After recovering somewhat with the Macintosh lineup, Apple again lost ground due to bad marketing during much of the 1990's. However, since Apple is a single company, other companies could not step in and "fill in the slack" when Apple stumbled. The result is that Apple is now primarily a niche product.

We thus conclude our introduction to the development of PC design and architecture which set the core computer configuration that is common today. However, there is one more important chapter in the history of computers, which will be the subject of the next lesson: the role of multimedia for the IBM PC, and also the emergence of the internet.