Divine opera

|

|

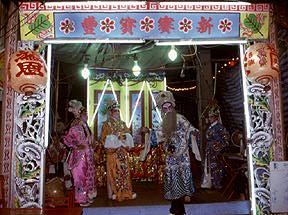

CULTURE: A revival is underway in Chinese opera circles in Thailand

with new troupes and more performances. But instead of enacting the old musical dramas

in front of human audiences, they are staging them for gods at sacred shrines |

|

Suthon Sukphisit When the ancestors of today's Thai Chinese community migrated south and arrived in this country, they brought their culture with them and preserved it in their new surroundings. Southern Chinese culinary arts and social structures - both in the community and in the family - were transplanted to Thailand where they continue to exist and evolve today. Also included in their cultural baggage were traditional Chinese forms of entertainment which brought them solace as they endured the rigors of beginning life anew in a place that was far from home. One form of popular theatre that they especially loved was ngiw, or Chinese opera. Theatres specialising in ngiw could once be found on roads like Yaowaraj and New Road which run through the heart of Bangkok's Chinatown. But as time passed by, the original audience began to die off, and the younger generation opted for a newer life style with different forms of entertainment. Performances in Bangkok of Chinese opera became less frequent and for a time it appeared that they were in danger of disappearing altogether. Today, however, there is a kind of ngiw revival in progress with new troupes and more performances. But there is a difference. Instead of enacting the old musical dramas in front of human audiences, they are staging them for gods at sacred shrines. When Chinese people settle together to form a community, they find comfort in their belief that they are shielded from harm by a protective deity who keeps watch over them. Traditionally, they express gratitude to this guardian spirit by building a shrine to which they make gestures of reverence every day. Then, once a year, they make their protecting god a more elaborate offering in the form of a ngiw performance which is enjoyed both by the deity it is dedicated to and by the members of the community who get to watch free of charge. But their chance to enjoy the operas is limited to once a year. Here in Thailand, as the Chinese communities like those centering around Yaowaraj and New Road grew larger, one performance a year was no longer enough. Theatre devoted especially to ngiw appeared, where audiences had to pay, but were able to view performances every night. They were highly popular, especially as they were the only form of entertainment available. At the height of their vogue there were many of them, including the Sin Faa, the Thien Kua Thien, the Sri Mueang, and the Chalerm Raat. Half a century ago the admission fee was 10-20 baht - expensive for the time but evidently no deterrent, as they did very good business. As time passed and tastes changed, audiences declined and business fell off to the point where, over the past 20 years or so, some of the ngiw theatres were converted into cinemas. Others were adapted to lower forms of entertainment; the Thien Kua Thien, for example, became a stripshow venue. The Sin Faa started showing films of ngiw instead of live performances, although every once in a while a live troupe from abroad would appear to those willing to pay the high entrance fee. Eventually this, too, came to an end, and today it sells videotapes of ngiwfrom China. Many other old theatres shut down altogether. A few survive as movie houses that specialise in porn. But ngiw theatres in their original form are completely gone. That does not mean, however, that Chinese opera has followed them into extinction. Today it has found a new home at the more than 15,000 sacred Chinese shrines found throughout Thailand.

Chinese Opera TroupsIn the past, all members of a ngiw troupe, both its leader and its actors, were ethnic Chinese. Training in the art began in early childhood - and only girls needed apply: both the hero and heroine roles were played by women. Parents generally welcomed the idea of their child leaving home to take up residence with a theatre troupe. But as Chinese opera declined and other professions became more lucrative and prestigious, parents became less receptive to having their children become ngiw performers. A career in business or a profession became a more desirable target. Many young Chinese became doctors, and found themselves highly respected in the community. Those who became Chinese opera singers had to work hard, and when they became too old to perform found themselves in the dilemma of having no skills that could be applied in other kinds of work. Despite the decline, however, work has always been available for Chinese opera performers. Troupes are hired for annual performances at shrines all over the country. Today, however, the heads of most ngiw troupes hire performers from Isan instead of Chinese singers, who are very scarce. It isn't necessary that the actors speak Chinese; all they have to do is memorise the words required by their parts. Not only stage roles are taken by Thais from Isan these days. The musicians, too, usually come from the Northeast. But all of this change makes very little difference to the audience, as those who understand all of what is going on up on stage are few and far between. Whatever the quality and accuracy of the performance, in most cases, it will do. At present there are about 30 ngiw troupes active in Thailand, not more than 10 of them made of up Chinese performers. Most of them have work to do all year long, as they are invited to perform at different community shrines. According to the usual pattern, a troupe might perform at a shrine in Bangkok for four days, then go to Chiang Mai for eight days, then perhaps on for another four-day stint in Udon Thani, and so on until the end of the year, after which the cycle begins again. Every three years, a given shrine may choose to hire another troupe, which would require the one that formerly played there to find a replacement, and then to arrange a new schedule for the year. All ngiw ensembles operate in this nomadic fashion. A typical ngiw troupe will consist of 35-45 members. Seven of them will be musicians who play the saw (a bowed string instrument), the khim (another stringed instrument, played with mallets), three kinds of drum, and two kinds of chaab (cymbals). Another 20 troupe members are actors and the rest are cooks, electricians, stagehands and the like. The troupe doesn't have to construct the stage as that is the responsibility of the shrine where the performance is being given. They may, however, bring a large piece of canvas to serve as a roof. Large shrines sometimes maintain permanent stages for Chinese opera performances. In adjusting to the requirements of different types of performances, when performing at a small shrine in Bangkok for only a couple of days, the troupe will reduce its forces, with only the necessary number of its members taking part. The cook, for example, may not go. But if it is necessary to pack up everything and depart for a new venue, they can do it very quickly. For example, if the troupe finishes a Bangkok performance at midnight, and must then travel to Chiang Mai to give another one the next day, they start packing as soon as the Bangkok show is over. It only takes an hour to pack everything up. Then they put it aboard a 10-wheel truck and take to the road. They'll arrive in the new location the following afternoon and by 7 p.m. they'll have the new stage set up and ready for a performance. Every ngiw troupe has its own jao, or presiding guardian spirit, which is usually represented by a wooden imaged carves in the style of a Chinese doll. When they arrive at a shrine to perform, they set their jao near the image of the one to whom the shrine is dedicated, as if their protecting spirit were making gesture of reverence to the one it is visiting. When the performance is given, it doesn't matter if no one comes to watch, because the troupe feels that the shrine's jao is watching. Usually there are children sitting on the ground in front of the stage, but they are usually just hanging around rather than actually watching the action on stage.

Ngiw Kae BonAlthough the Chinese opera theatres of Yaowaraj and New Road are all gone, those people remaining, most of them elderly, who still love watching ngiw can still see it when the spirit moves them. Performances still take place regularly at the shrine to Jao Phaw Suea on Unaakan Road. The Jao Phaw Suea Shrine is a highly revered site that constantly draws crowds of people who believe it to be sacred. Some believers visit the shrine to make requests of it for various things, and if their wishes are granted, they express gratitude by offering a ngiw performance. As a result, Chinese opera can be seen there every day except Saturday and Sunday. The administrative office of the Jao Phaw Suea Shrine must hire troupes to give these performances, known as kae bon, daily. Each is hired for three years, and it is a condition that the performers must be Chinese, not Thais from Isan. The members of the troupe sit at the shrine from 10 a.m. until 4 p.m. each weekday. They do not wear the elaborate makeup associated with ngiw, and they wear ordinary clothes. They can be hired for the kae bon performances at the rate of 200 baht for five minutes. It often happens, however, that someone will want to hire the troupe to present a kae bon Chinese opera both during the day and at night. This means that they will perform during the day, and then continue from 7 p.m. until 10 p.m. In such cases they will also have to wear makeup and appear in costume. The fee for an event of this kind is 20,000 baht, and it must be arranged in advance. At such a performance, the people who form the audience are generally advanced in years. Anyone happening upon a sponsored ngiw of this type will notice an elderly group of spectators watching it with great concentration. Ngiw once enthralled Chinese migrants who had come to settle in a new land. Although old audiences dwindled and newer generations lost their taste for it, performers kept the art essentially as it had been in the past, retaining the original Chinese language and refusing to offer the operas in Thai. But today, ngiw artists do not entertain hopes of winning new viewers from among those who neither speak nor understand Chinese. They are performing for divine beings, not for living people. As a result, Chinese opera as performed in Thailand is odd. It has no well-known stars of the kind found in the other performing arts. And there is never any applause. Spirits who reside in shrines do not let on which artist brings them the most pleasure, and react to even the finest performance with silence.

|

© The Post Publishing Public Co., Ltd. All rights reserved 1997

Contact the Bangkok Post

Web Comments: Webmaster

Last Modified: 12/12/97; 10:02:53 AM