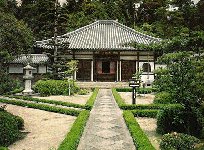

The Horai garden at Daichiji is maintained by Shimizu Toshiharu, a

priest who teaches social

studies at nearby Shirayama Middle School. His wife is usually the one

to show people around,

though. As one walks along the corridors to the viewing pavilio n, two

things are striking: the

strong smell of cypress and an odd plunk....plunk....plunk....coming

from the loudspeakers

attached to the ceiling. The former is from recent construction work. On

February 2, 1993, a

particularly heavy snow caused the roof of the main hall to cave in. The

building has since been

entirely rebuilt in cypress to the precise dimensions of the original.

The latter, an acoustic addition

to the viewing experience, is an amplified recording of water dropping

into a suikinkutsu echo

chamber. The original concept of the garden was also an acoustic one.

The smooth, soft sound of

the wind blowing through the pines growing on the site in th e 17th

century was a reminder of the

sea and islands depicted in the garden.

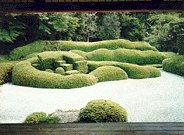

The walk along the corridor is short and one soon arrives at Horai

Teien. A massing of shaped

green azaleas set against the natural (though constructed) hillside

behind and white sand below is

the primary feature of the garden. (plan to be attached) Marc Trieb sees

the Horai garden as an

example of the juxtaposed modes of formality (shin, gyo, so) that "have

served as a generative

force behind much of Japanese art and environmental design." The shea

red okarikomi shrubs

suggest a treasure ship being tossed among undulating waves of the sea.

Azalea cubes and spheres

form the treasure in the ship piled around the almos t invisible stones

that are said to represent the

seven gods of fortune. To the right of the ship's prow is a separate

rounded mass of azalea with a

protruding stone forming a turtle-shaped kameshima beneath the eaves of

the building. Behind the

kameshima, running perpendicular to the viewing platform and providing a

geometric counterpoint

to the waves is a line of hinoki (cypress). In the foreground below the

viewing pavilion's steps, is a

round, flattened stone flanked by two more small azaleas. This is meant

to provide a place for

zazen meditation while viewing the garden.

The purplish-brown of winter foliage gives way to a bright floral

display from late May to mid

June. This becomes lush green foliage by August and September. In

autumn, the momiji maple

trees on the hillside behind burst into flame.

The garden was built in the early decades after the Tokugawa government

restored peace and

stability at the beginning of the 17th century. It is unclear, however,

precisely when the garden was

constructed. The current pamphlet and interpretive signs both claim

Kobori Enshu (1579-1647)

himself designed the garden in the late 1620's. This is certainly

possible, but, like many of the

gardens with which Enshu is credited, his connection here is debatable.

Th e temple was still in

ruins during Enshu's lifetime and it seems unlikely the

garden would have been built

before the temple buildings were restored in. This did not occur until

twenty years after Enshu's

death. In fact, a number of referenc es refer to his grandson being

responsible for this garden.

Enshu's fame as a designer and arbiter of taste was so profound, it was

not unusual for successive

generations of designers to adopt his name, thereby lending legitimacy

to their work.

The juxtaposition of an okarikomi azalea garden sandwiched between

temple buildings and a

hillside is not unique to this garden. The garden at Raikyuji temple in

Okayama is structurally quite

similar, the only differences between the two being the sli ghtly

earlier construction data at Raikyuji

and the sharper, more choppy lines of the topiary. The smoother lines at

Daichiji probably reflect

the lesser role of the stone insertions.

|

The temple at Daichiji dates back 1200 years to its 8th century founding

by Gyoki (670-749), a

prominent Korean-born priest that travelled extensively spreading the

Buddhist doctrine.

While the karesansui of Horai Garden is the most significant feature on

the temple grounds today,

it is one of the more recent transformations of the site. Gyoki is

thought to have originally dug a p

ond here in the shape of the Chinese character kokoro (heart/soul/mind.)

Similar kokoro ponds

(see Saihoji) have appeared in numerous Japanese gardens, even to the

present, but they appear

to have been particularly popular in the latter centuries of the Heian

period (794-1185) after the

importation of Buddhism from China (538AD). The first temple building

was erected on an island

located in the center of this pond. An unusual feature was the pond's

use as an irrigation resevoir

for nearby fields. The pond no longer exists, however, and the

irrigation function is now served by

two much larger resevoirs just to the west and northwest of the temple

grounds. The temple was

known as Kantansan Seirenji in these early centuries and was established

as a pray er site for

protection of the state.

In the early 1320's the temple changed hands from the Tendai branch of

esoteric Buddhism to a

Zen sect based at Kyoto's Tofukuji Temple. Long neglected, the grounds

were restored and seven

additional structures added.

In 1577 the entire temple was burned to the ground during one of many

military campaigns that

would eventually lead to the reunification of Japan under the Tokugawa

regime. The temple was

restored until 1667 to celebrate the completion of Minakuchi-jo Castle

nearby. The present

Buddha Hall(butsuden), chashitsu, and priest's quarters (hojo) date from

this time. The name of the

temple was also changed at this point. Its proximity to two large

resevoirs lent inspiration for its

present appelation, Dai chiji, the "Temple of the Large Pond."

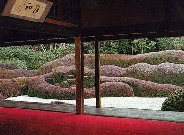

In addition to Horai Teien, a second garden between the teahouse and

storeroom contains pines

resembling dancing cranes. The storehouse background is kept whitewashed

to reflect the moon

during evening tea ceremonies, creating the illusion of an open garden

in a very confined space.

Here, the garden is an abstraction of a mountain view with a stream

flowing through a valley.

Other examples of clipped karikomi appear around an ancient (over 300

years old) pine tree in

the foregarden at the entrance of the temple. While the venerable pine

tree has been there for

some time and is qu ite impressive, the entrance garden is a 20th

century addition of little note.