Brno (1902-1932)

Before the War

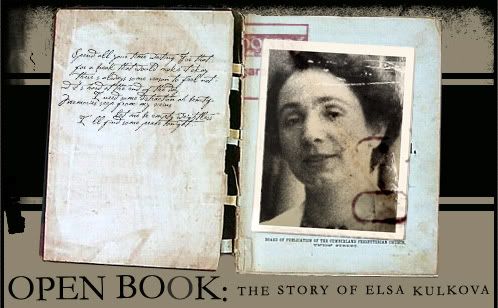

Born on April 14, 1902, Elsa was the firstborn child of Eduard and Ema Skutecky, Moravian Jews. Elsa and her two siblings grew up in the flourishing city of Brno, Czechoslovakia. Czechoslovakia had gained its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire after World War I, and was composed of the

provinces Bohemia, Moravia, Slovakia, and the Transcarpathian Ukraine. Czechoslovakia was quite diverse at this time as well, containing Czechs, Slovaks, Ukranians, Hungarians, and Jews. Brno was located in the province of Moravia. Because it was urbanized, Elsa probably encountered this diversity in her everyday life.

provinces Bohemia, Moravia, Slovakia, and the Transcarpathian Ukraine. Czechoslovakia was quite diverse at this time as well, containing Czechs, Slovaks, Ukranians, Hungarians, and Jews. Brno was located in the province of Moravia. Because it was urbanized, Elsa probably encountered this diversity in her everyday life.

Elsa’s father owned a shipping business, and Elsa’s family led a life of privilege. With its independence in 1918, Brno also saw a surge in Czech schooling and culture. However, at the time of Elsa’s graduation, there were only 84 Czech-speaking schools in Brno. Still, Elsa was one of the many children to attend a German-language secondary school, from which she graduated in 1920. Her brother may have gone to the new Czech University, which opened in 1919. Elsa enjoyed time with her family, as well as time out on the town. Elsa would have done her food shopping in Brno’s market district, going to the fruit and vegetable markets on Na bastach Street and Novobranska Street.

Elsa had gotten married and moved with her husband to Bratislava. However, her stint in Bratislava was brief; the marriage failed and Elsa returned to Brno in 1926, where she opened a millinery shop. Like her father, Elsa was gifted in the art of enterprise.

Brno was quickly becoming a more heavily industrialized city in the beginning of the century. Its biggest industries were metalworking and textiles. However, Brno’s industries were hard-hit in the economic crisis of the 1930’s. World War II also disrupted business in Brno. Jewish businesses were reposed by the state and Czech businesses were diverted to war production; any resistance was suppressed.

Politics in Brno at this time foreshadowed the dark years to come. Various Czech parties (The Czechoslovak National Socialist Party, Czechoslovak Social Democratic Workers' Party, Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, Czechoslovak People's Party) contended for power between the years 1920-1935, each gaining its moment in the spotlight. However, in 1935 the German Sudeten Party gained a foothold; the influence of this party would lead to the occupation of Czechoslovakia by Germany in 1939.

Olomouc and Brno (1933-1942)

Occupied Bohemia-Moravia

After running her little business for several years, Elsa married Robert Kulka on May 24, 1933. The couple moved to Olomouc, Robert’s hometown. A year later Elsa gave birth to her only child, whom she and Robert named Thomas. When Elsa’s father died in 1937, the Kulkas returned to Brno to assume leadership of his shipping company. Elsa’s widowed mother moved in with them.

After running her little business for several years, Elsa married Robert Kulka on May 24, 1933. The couple moved to Olomouc, Robert’s hometown. A year later Elsa gave birth to her only child, whom she and Robert named Thomas. When Elsa’s father died in 1937, the Kulkas returned to Brno to assume leadership of his shipping company. Elsa’s widowed mother moved in with them.

Hitler had felt the right to annex Czechoslovakia, the population of which was 25% German, into the Third Reich. In 1938 Hitler issued the ultamatum that he would start a war in Europe unless the Sudetenland, the border province of Czechoslovakia that was heavily German, was annexed to Germany. In the year 1938, Sudentenland was ceded to Germany when the world powers signed the Munich Pact that agreed to Hitler’s demands in an attempt to avoid conflict. Still, Hitler invaded Bohemia-Moravia in 1939, and it became a German protectorate.

Many business owners in the former Czechoslovakia lost their livelihood under German occupation, and the Kulkas were no exception. The Germans started their restrictions on Jews. Beginning in 1938 Jews had to register their property, which made it hard to get the collateral needed to emigrate, even though the Nazis formally encouraged emigration.

Had Elsa wanted to write to a friend in Omoluc to ask about his condition, she would have had to pick her words carefully. This is because shortly after the occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1939, the SS imposed what it called “currency control” of mail.

This was actually a secret censorship. There were currency control offices in the Brno 2 post office, the Olomouc 2 post office, and many others in Czechoslovakia. Senders of inspected mail that the SS considered insurrectionist would be imprisoned.

This was actually a secret censorship. There were currency control offices in the Brno 2 post office, the Olomouc 2 post office, and many others in Czechoslovakia. Senders of inspected mail that the SS considered insurrectionist would be imprisoned.

The Kulkas were evicted on January 2, 1940. Elsa’s brother and sister, also in Brno, chose to emigrate to Palestine. Robert, however, wanted to try to stay in Brno to save the family business. A year later, Elsa was forced to sell the shipping business that her father started from scratch for only 200 Czechhhoslovak crowns—only $10.

Bohemia-Moravia was home to an estimated 90,000 Jews in 1941 when the Nazis began the deportation of Jews to ghettos. Most of these Jews were deported to Thereinstadt, and from there to eastern European death camps like Sobibor and Auschwitz-Birkenau where most were killed. Less than 2,000 Jews remained in Bohemia-Moravia after the war.

Bohemia-Moravia was home to an estimated 90,000 Jews in 1941 when the Nazis began the deportation of Jews to ghettos. Most of these Jews were deported to Thereinstadt, and from there to eastern European death camps like Sobibor and Auschwitz-Birkenau where most were killed. Less than 2,000 Jews remained in Bohemia-Moravia after the war.

Terezín (March-May 1942)

The Privileged Ghetto

As a Czech and business owner, Elsa was a so-called “privileged” Jew, meaning that she and her family got the “privilege” of being sent to the Thereinstadt ghetto in Bohemia-Moravia with other “privileged” individuals—those who had

served in the Great War, wealthy, or otherwise prominent Jews—on March 31, 1942. Thereinstadt housed Czech, Dutch, German, and Danish Jews. Elsa’s family was deported there with the belief that they were being moved to do forced labor for the Nazis. Thereinstadt was the Nazi’s model ghetto (they allowed the Red Cross to investigate it in 1944, although they staged a farce to make it seem humane) and as such conditions there were slightly better than in other ghettos. Nazi propaganda was audacious enough to deem it a “spa town.” Still, “slightly” is the operative word; Thereinstadt, or Terezín as the Czechs called it, was the home to a total of 141,184 Jews during the war. At its liberation in 1945, 16,832 remained in Terezín; one-fourth of these survivors died of disease shortly afterwards.

served in the Great War, wealthy, or otherwise prominent Jews—on March 31, 1942. Thereinstadt housed Czech, Dutch, German, and Danish Jews. Elsa’s family was deported there with the belief that they were being moved to do forced labor for the Nazis. Thereinstadt was the Nazi’s model ghetto (they allowed the Red Cross to investigate it in 1944, although they staged a farce to make it seem humane) and as such conditions there were slightly better than in other ghettos. Nazi propaganda was audacious enough to deem it a “spa town.” Still, “slightly” is the operative word; Thereinstadt, or Terezín as the Czechs called it, was the home to a total of 141,184 Jews during the war. At its liberation in 1945, 16,832 remained in Terezín; one-fourth of these survivors died of disease shortly afterwards.

Jewish ghettos existed prior to the war, but these were “free” ghettos, where Jews had to stay inside the ghetto walls at night but could go and come as they pleased during the daytime. The ghettos of the Second World War were purposely designed to breed instability. Unreasonably small, people were forced to crowd together in small tenement-like houses. Elsa slept in a two-level bunk bed that she shared with 10-12 other women. Close quarters such as this, combined with poor sanitation and nutrition, were breeding grounds for disease. Of the few Jews who weren’t sent to a concentration camp, most died of disease in Thereinstadt.

Jewish ghettos existed prior to the war, but these were “free” ghettos, where Jews had to stay inside the ghetto walls at night but could go and come as they pleased during the daytime. The ghettos of the Second World War were purposely designed to breed instability. Unreasonably small, people were forced to crowd together in small tenement-like houses. Elsa slept in a two-level bunk bed that she shared with 10-12 other women. Close quarters such as this, combined with poor sanitation and nutrition, were breeding grounds for disease. Of the few Jews who weren’t sent to a concentration camp, most died of disease in Thereinstadt.

Despite their dire situation, the captives of Terezín kept their morale up and maintained their cultural life. Intellectuals gave lectures, orating to packed buildings. Artists produced drawings and paintings. Composers and actors taught their art and gave performances. Terezín even had a library of more than 60,000 books. The Jews also continued to defy the Nazi’s will by revering Jewish laws, holidays, and customs.

Even if they were starving, the Jews still fasted on the high holy day of Yom Kippur to show their religious devotion couldn’t be suppressed. Many people maintained contacts with the outside world through mail and postcards, although delivery was slow and subject to being read by the SS. Elsa and her family were able to maintain a semblance of normal family life in the ghetto as unit. However, this fragile peace and family unity were soon to be sundered forever.

Even if they were starving, the Jews still fasted on the high holy day of Yom Kippur to show their religious devotion couldn’t be suppressed. Many people maintained contacts with the outside world through mail and postcards, although delivery was slow and subject to being read by the SS. Elsa and her family were able to maintain a semblance of normal family life in the ghetto as unit. However, this fragile peace and family unity were soon to be sundered forever.

Located off of significant railroad tracks, Terezín was not only a ghetto; it was a way station. Residency in Terezín was temporary for everyone unfortunate enough to be sent there: Beginning in 1942 Terezín deported Jews by the thousands every month to their deaths in eastern European death camps Majdanek, Treblinka, Sobibor, and Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Ossowa (May-September 1942)

Extermination Through Work

At 40 and 52 years old, respectively, Elsa and her husband were still stout enough to work. Her elderly mother and seven-year-old son were not; both were sent to the Sobibor death camp on May 9, where they were gassed upon arrival. Ema was 62. Thomas was only 7 years old. Their sad fates coincided with many other Jews who weren’t robust enough for the SS work standards. However, the final days of those chosen to do hard labor was arguably worse. On May 9 Elsa and Robert were deported to the labor camp Ossowa.

At 40 and 52 years old, respectively, Elsa and her husband were still stout enough to work. Her elderly mother and seven-year-old son were not; both were sent to the Sobibor death camp on May 9, where they were gassed upon arrival. Ema was 62. Thomas was only 7 years old. Their sad fates coincided with many other Jews who weren’t robust enough for the SS work standards. However, the final days of those chosen to do hard labor was arguably worse. On May 9 Elsa and Robert were deported to the labor camp Ossowa.

The Nazis used Jewish slave labor as the manpower to produce all sorts of goods for the German war effort. Concentration camps manufactured everything from uniforms to cars to bombs. Much of the work was pointless, serving no purpose other than “extermination through work”—a Nazi philosophy quite contrary to the deceptive phrase “arbeit macht frei” (“work will make you free”) that was emblazoned over the entrances to many concentration camps. The work at labor camps was hard, and the Jew slaves were expected to work in harsh conditions and given little or no food. Prisoners tried to get indoor work if they could since it wasn’t as strenuous and meant that they could sometimes steal little scraps from the workroom. Outdoor work entailed hard labor like stone hauling in any season or weather, every day. As a woman, Elsa wouldn’t have automatic assignment to lighter work. The Nazis were trying to work the Jews to death, no matter their gender.

The average day in a labor camp that Elsa would have experienced started with a wake-up call at 4am. This was followed by a role-call which the Jewish prisoners sometimes had to stand through hours; some died of fatigue from it. At 6am the 11-hour workday began, with only a few short breaks. At 9pm there was a night role-call and then the workers were sent back to their barracks. During the workday, the SS used beatings for even minor rule-breaking and public executions to terrorize the workers and keep them in line. Hygiene in labor camps was predictably bad, and many Jews succumbed to disease. Robert died after two months at Ossowa. Four months later, exhausted, Elsa died as well at the age of 40.

The average day in a labor camp that Elsa would have experienced started with a wake-up call at 4am. This was followed by a role-call which the Jewish prisoners sometimes had to stand through hours; some died of fatigue from it. At 6am the 11-hour workday began, with only a few short breaks. At 9pm there was a night role-call and then the workers were sent back to their barracks. During the workday, the SS used beatings for even minor rule-breaking and public executions to terrorize the workers and keep them in line. Hygiene in labor camps was predictably bad, and many Jews succumbed to disease. Robert died after two months at Ossowa. Four months later, exhausted, Elsa died as well at the age of 40.

Afterwards

Although Elsa didn’t survive the war, some very lucky Jews did. After Germany’s capitulation the concentration camps and ghettos were liberated. Many people went to DP (Displaced Persons) camps, some of which were horrifyingly on the same sites as ghettos had once been, where they received food, healthcare, and clothing. Their homes and money lost, their families slaughtered, the survivors of the Holocaust faced a new set of problems. Where could they go and how could they start their lives anew? With the resurgence of Zionism, some Jews were able to return to the Jewish homeland in Palestine. However, this was a British protectorate and Britain was very staunch about enforcing immigration quotas. Anti-Semitism raged through most of Europe, so some Jews sought asylum overseas. Jews went to the US and Canada, although immigration quotas for Jewish refugees were limited in these countries as well. The Dominican Republic accepted the largest about of Jews, and became a popular destination point. Other Jews went to Australia, New Zealand, South America, and a few even went to China. These Holocaust survivors would forever live with the scars, both physical and mental, of their horrible experience. Most have tattoos of serial numbers and vivid memories of murder. As they will always remember, it is important that we who follow them never forget the atrocities of the Holocaust, and work to make sure that this history is never repeated.