|

|

|

The Jordan Valley |

|

|

|

The Jordan Valley,

which extends down the entire western flank of Jordan, is

the country's most distinctive natural feature. The Jordan

Valley forms part of the Great Rift Valley of Africa, which

extends down from southern Turkey through Lebanon and Syria

to the salty depression of the Dead Sea, where it continues

south through Aqaba and the Red Sea to eastern Africa. This

fissure was created 20 million years ago by shifting tectonic

plates.

The

River Jordan

© Jordan Tourism Board

The

northern segment of the Jordan Valley, known in Arabic as

the Ghor, is the nation's most fertile region. It contains

the Jordan River and extends from the northern border down

to the Dead Sea. The Jordan River rises from several sources,

mainly the Anti-Lebanon Mountains in Syria, and flows down

into Lake Tiberias (the Sea of Galilee), 212 meters below

sea level. It then drains into the Dead Sea which, at 407

meters below sea level, is the lowest point on earth. The

river is between 20 and 30 meters wide near its endpoint.

Its flow has been much reduced and its salinity increased

because significant amounts have been diverted for irrigational

uses.

Several degrees warmer than the rest of the country, its year-round

agricultural climate, fertile soils, higher winter rainfall

and extensive summer irrigation have made the Ghor the food

bowl of Jordan.

The Jordan River ends at the Dead Sea, which, at a level of

over 407 meters below sea level, is the lowest place on the

earth's surface. It is landlocked and fed by the Jordan River

and run-off from side wadis. With no outlet to the sea, intense

evaporation concentrates its mineral salts and produces a

hypersaline solution. The sea is saturated with salt and minerals–its

salt content is about eight times higher than that of the

world's ocean–and earns its name by virtue of the fact

that it supports no indigenous plant or animal life. The Dead

Sea and the neighboring Zarqa Ma'een hot springs are famous

for their therapeutic mineral waters, drawing visitors from

all over the world.

Dead Sea at night.

© Zohra

South

of the Dead Sea, the Jordan Valley runs on through hot, dry

Wadi ‘Araba. This spectacular valley is 155 kilometers

long and is known for the sheer, barren sides of its mountains.

Its primary economic contribution is through potash mining.

Wadi ‘Araba rises from 300 meters below sea level at

its northern end to 355 meters above sea level at Jabal Risha,

and then drops down again to sea level at Aqaba.

The seaside city of Aqaba is Jordan's only outlet to the sea.

Its 40 kilometer-long coastline houses not only a tourist

resort and Jordan's only port, but also some of the finest

coral reefs in the world. The rich marine life of these reefs

provides excellent opportunities for snorkeling and diving.

|

|

|

|

|

The Mountain Heights |

|

|

|

The

highlands of Jordan separate the Jordan Valley and its margins

from the plains of the eastern desert. This region extends

the entire length of the western part of the country, and

hosts most of Jordan's main population centers, including

Amman, Zarqa, Irbid and Karak. We know that ancient peoples

found the area inviting as well, since one can visit the ruins

of Jerash, Karak, Madaba, Petra and other historical sites

which are found in the Mountain Heights Plateau. These areas

receive Jordan's highest rainfall, and are the most richly

vegetated in the country.

Wadi

Mujib.

© Jad Al Younis, Discovery Eco-Tourism

The

region, which extends from Umm Qais in the north to Ras an-Naqab

in the south, is intersected by a number of valleys and riverbeds

known as wadis. The Arabic word wadi means a watercourse valley

which may or may not flow with water after substantial rainfall.

All of the wadis which intersect this plateau, including Wadi

Mujib, Wadi Mousa, Wadi Hassa and Wadi Zarqa, eventually flow

into the Jordan River, the Dead Sea or the usually-dry Jordan

Rift. Elevation in the highlands varies considerably, from

600 meters to about 1,500 meters above sea level, with temperature

and rainfall patterns varying accordingly.

The northern part of the Mountain Heights Plateau, known as

the northern highlands, extends southwards from Umm Qais to

just north of Amman, and displays a typical Mediterranean

climate and vegetation. This region was known historically

as the Land of Gilead, and is characterized by higher elevations

and cooler temperatures.

South and east of the northern highlands are the northern

steppes, which serve as a buffer between the highlands and

the eastern desert. The area, which extends from Irbid through

Mafraq and Madaba all the way south to Karak, was formerly

covered in steppe vegetation. Much of this has been lost to

desertification, however. In the south, the Sharra highlands

extend from Shobak south to Ras an-Naqab. This high altitude

plain receives little annual rainfall and is consequently

lightly vegetated.

|

|

|

|

|

The Eastern Desert (Badia) |

|

|

|

Comprising

around 75% of Jordan, this area of desert and desert steppe

is part of what is known as the North Arab Desert. It stretches

into Syria, Iraq and Saudi Arabia, with elevations varying

between 600 and 900 meters above sea level. Climate in the

Badia varies widely between day and night, and between summer

and winter. Daytime summer temperatures can exceed 40°C,

while winter nights can be very cold, dry and windy. Rainfall

is minimal throughout the year, averaging less than 50 millimeters

annually. Although all the regions of the Badia (or desert)

are united by their harsh desert climate, similar vegetation

types and sparse concentrations of population, they vary considerably

according to their underlying geology.

The volcanic formations of the northern Basalt Desert extend

into Syria and Saudi Arabia, and are recognizable by the black

basalt boulders which cover the landscape. East of the Basalt

Desert, the Rweishid Desert is an undulating limestone plateau

which extends to the Iraqi border. There is some grassland

in this area, and some agriculture is practiced there. Northeast

of Amman, the Eastern Desert is crossed by a multitude of

vegetated wadis, and includes the Azraq Oasis and the Shomari

Wildlife Reserve.

To the south of Amman is the Central Desert, while Wadi Sarhan

on Jordan's eastern border drains north into Azraq. Al-Jafr

Basin, south of the Central Desert, is crossed by a number

of broad, sparsely-vegetated wadis. South of al-Jafr and east

of the Rum Desert, al-Mudawwara Desert is characterized by

isolated hills and low rocky mountains separated by broad,

sandy wadis. The most famous desert in Jordan is the Rum Desert,

home of the wondrous Wadi Rum landscape. Towering sandstone

mesas dominate this arid area, producing one of the most fantastic

desert-scapes in the world.

|

|

|

|

|

Wildlife

and Vegetation |

|

|

|

Arabian

Oryx at the Shomari Reserve.

©

Jordan Tourism Board

Throughout

history, the land of Jordan has been renowned for its luxurious

vegetation and wildlife. Ancient mosaics and stone engravings

in Jawa and Wadi Qatif show pictures of oryx, Capra ibex and

oxen. Known in the Bible as the "land of milk and honey,"

the area was described by more recent historians and travelers

as green and rich in wildlife. During the 20th century, however,

the health of Jordan's natural habitat has declined significantly.

Problems such as desertification, drought and overhunting

have damaged the natural landscape and will take many years

to rectify.

Fortunately, Jordanians have taken great strides in recent

years toward stopping and reversing the decline of their beautiful

natural heritage. Even now, the Kingdom retains a rich diversity

of animal and plant life that varies between the Jordan Valley,

the Mountain Heights Plateau and the Badia Desert region.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

Jordanian habitat and its wildlife communities have undergone

significant changes over the centuries and continue to be

threatened by a number of factors. A rapidly expanding population,

industrial pollution, wildlife hunting and habitat loss due

to development have taken a toll on Jordan's wildlife population.

Jordan's absorption of hundreds of thousands of people since

1948 has resulted in the over-exploitation of many of its

natural resources, and the country's severe shortage of water

has led to the draining of underwater aquifers and damage

to the Azraq Oasis.

In recent decades, Jordan has addressed these and other threats

to the environment, beginning the process of reversing environmental

decline. A true foundation of environmental protection requires

awareness upon the part of the population, and a number of

governmental and non-governmental organizations are actively

involved in educating the populace about environmental issues.

Jordan's Ministry of Education is also introducing new literature

into the government schools' curriculum to promote awareness

of environmental issues among the young students.

The National Strategy presents specific recommendations for

Jordan on a sectoral basis, addressing the areas of agriculture,

air pollution, coastal and marine life, antiquities and cultural

resources, mineral resources, wildlife and habitat preservation,

population and settlement patterns, and water resources. The

plan places considerable emphasis throughout on the conservation

of water and agriculturally productive land, of which the

contamination or loss of either would bring swift and significant

consequences to Jordan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

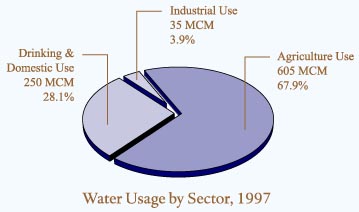

The

gravest environmental challenge that Jordan faces today is

the scarcity of water. Indeed, water is the decisive factor

in the population/resources equation. Whereas water resources

in Jordan have fluctuated around a stationary average, the

country's population has continued to rise. A high rate of

natural population growth, combined with periodic massive

influxes of refugees, has transformed a comfortable balance

between population and water in the first half of this century

into a chronic and worsening imbalance in the second half.

The situation has been exacerbated by the fact that Jordan

shares most of its surface water resources with neighboring

countries, whose control has partially deprived Jordan of

its fair share of water. Current use already exceeds renewable

supply. The deficit is covered by the unsustainable practice

of overdrawing highland aquifers, resulting in lowered water

tables and declining water quality. On a per capita basis,

Jordan has one of the lowest levels of water resources in

the world. Most experts consider countries with a per capita

water production below 1,000 cubic meters per year to be water-poor

countries. In 1997, Jordanians consumed a total of 882 million

cubic meters (MCM). In 1996, per capita share of water was

less than 175 for all uses. This placed Jordan at only 20

percent of the water poverty level. The extent of the crisis

is further demonstrated by the fact that, from the 1997 total

of 882 MCM, around 225 MCM was pumped from ground water over

and above the level of sustainable yield. Likewise, about

70 MCM was pumped from non-renewable fossil water in the southeast

of the country.With Jordan's population expected to continue

to rise, the gap between water supply and demand threatens

to widen significantly. By the year 2025, if current trends

continue, per capita water supply will fall from the current

200 cubic meters per person to only 91 cubic meters, putting

Jordan in the category of having an absolute water shortage.

Only two years from now, in the year 2000, Jordan is expected

to require 1257 MCM of water to cover minimum domestic, industrial

and agricultural needs. Quantities from sources available

by that time will not exceed 960 MCM, bringing the deficit

to 297 MCM. Of the required total, 61 percent will be needed

to maintain existing agricultural activities, 31 percent for

domestic consumption, and six percent for industrial uses.Responding

to the challenge, the government has adopted a multi-faceted

approach designed to both reduce demand as well as increase

supply. The peace treaty signed in 1994 by Jordan and Israel

guaranteed Jordan its right to an additional 215 MCM of water

annually through new dams, diversion structures, pipelines

and a desalination/purification plant. Of this 215 MCM, Jordan

is already receiving between 55 and 60 MCM of water from across

the border with Israel through a newly-built pipeline. Jordan

is also entitled to build a series of dams on the Jordan and

Yarmouk rivers to impound its share of flood waters. To this

end, the Karama Dam in the Jordan Valley has been built to

store 55 MCM of water, mainly from the Yarmouk, and its yield

will be used to help irrigate some

6000 hectares in the southern Jordan Valley.

|

|

|

|

|

|