|

Copyright Johns Hopkins University Press Spring 2003

In

his 1563 edition of Actes and Monuments, John Foxe lingers over the

death of Sir James Hales. Hales had been a supporter of Edward VI's

efforts to entrench ecclesiastical reform, and with Mary's ascension he

was thrown into prison and harassed into recanting his Protestant

loyalty. Foxe explains that after an attempted suicide Hales was

released; he then, "either for the greatnes of hys sorow, or for lacke

of reste and reason, or for lacke of good counsell, or for that he

would avoyd the necessity of hearing masse," drowned himself at his

estate in Kent.1 Since suicide represented not only the cardinal sin of

despair but was, as a contemporary legal scholar wrote, an "offence

against God, against the king, and against Nature," Hales's death

became a "propaganda disaster" for the Protestants. Conservative

churchmen took immediate advantage-Stephen Gardiner used Hales's case

to declare Protestantism a "doctrine of desperation" (1116) in Star

Chamber. Protestant historiographers thus felt some urgency in

refurbishing Hales's reputation; Raphael Holinshed put as positive a

spin as he could on Hales's death, while Foxe tried to induct him into

the fellowship of Protestant saints.2 Foxes approach to justifying

Hales's suicide is distinct from other Protestant apologists; rather

than placing responsibility on either Hales's lack of sound mind or his

coercion by his persecutors, Foxe attempts to justify the act of

suicide itself.3 Foxe cites early Christians who, while suffering under

the persecution of the early church, kept "their fayth and religion

unspoted" (1116) by suicide, asking rhetorically "how many examples

have we in the first persecutions of the Churche, of those men who

willynglye having killed & drowned themselves, onely upon an honest

cause ye bare out the matter, are yet registred in the workes of worthy

writers to their perpetuall prayse?" (1116).4 Foxe lays out multiple

examples taken from patristic texts (particularly Eusebius) of early

Christians who "did cast downe themselves headlong & brake their

owne neckes" so as "to avoyde suche horrible pollution of themselves"

through "sacrifice to heathen idols" (1116).

By aligning the

defense of true religious faith with the preservation of purity which

may be justly defended with self-destruction, Foxe extends his defense

of suicide to examples that conflate the defense of religious belief

with the defense of physical chastity. Foxe cites the "virgins of

Antioch... who to the end they might not defyle themselves with

uncleannesse, and with ydolatrie through the perswasion of their

mother, casting themselves headlong into a river together with their

mother, did fordo themselves, although not in the same water, yet after

the same manner of drowning, as this maister Hales did" (1116-17). Foxe

follows the virgins of Antioch with a story of "Brassila Dyrrachina"

who, when a "yong man" was "about to deflowre her ... fayned her selfe

to be a witche" and convinced her attacker that she would "geve him an

herb, which shoulde preserve him from all kynde of weapons." To prove

it, she "layde the herbe upon her owne throte" and had him test it; and

"so with ye losse of her life, her virginite was saved" (1117).5 Foxe

also tells of the "death of Sophronia a Matron of Rome, who when she

was required of Marentius the tiraunt to bee defiled... went into her

Chaumber, and with a weapon thrust her self through the brest and dyed"

(1117). And while these women were not directly defending their faith

with their suicides, Foxe concludes with the question, "who can tell,

whether master Hales, meaning to avoid the pollution of the Masse, did

likewise use the same kinde of death to kepe his faith undefiled,

wherof there ought to be as greate respect and greater to, then of the

chastitye of the bodye?" (1117). Foxe thus validates suicide as a

defense against a violation not of Christian spiritual virtue, but of

physical chastity,

And so, in Foxes argument, the hierarchical

tyranny of the Catholic oppression ceases to be an act of religious

persecution but is reconfigured as an act of erotic violence, exposing

a powerful erotic scripting of religious persecution that reverberates

throughout Foxes work. In this essay I examine this integration of

eroticism and suffering in early modern martyrology, an integration

which produces not only a historically specific form of interiority but

also a powerful mechanism for nonconformist evangelism. I will first

examine the figure of the woman martyr (Anne Askew in particular) who

is authorized to speak within a specifically early modern narrative

formulation of rape. I contend that the intersection of sexuality and

suffering upon the female body was vital to the development of the

activist, self-justifying, and self-contained individual who would

become the dominant model of Protestant subjectivity. This produced the

Protestant martyr-subject in discursive terms that were primarily

gendered female, even as most martyrs were men. I argue, therefore,

that as male bodies were placed within this narrative, in one sense the

feminizing erotics of rape infused reformist martyrology with the image

of the raped man, invoking the abject erotics of sodomy as a weapon

against Catholic persecution. Yet since early modern homoeroticism was

not simply analogous to heteroeroticism, I contend that the

libidinalized suffering of martyrs simultaneously energized the tropes

of male friendship, an erotic discourse which, while central to

dominant social, political and religious alliances, was often

discursively indistinguishable from sodomy.6 Foxes text thus points to

an interaction of "productive" and "disruptive" homoeroticisms that

work in cooperation to structure the male subject of martyrology. And

so, with the suffering body as the nexus of subject formation,

historically specific discourses of desire intersect to mold radically

modern versions of the female subject while at the same time generating

distinctly conservative forms of male homosocial alliance.

I. SUFFERING SUBJECTS

The

most extreme bodily pain is, without a doubt, central to Foxes work. In

fact, the dramatic display of martyrs suffering in relentlessly graphic

fashion is part of the realism that is one of the key distinctions

between the emergent form of Protestant martyrology and its medieval

Catholic forebears.' Traditional hagiographies had focused on the

martyr's release from pain, as in Eusebius,s church history when Bishop

Polycarp's singed flesh gave only the smell of incense, causing him to

be put to a comparatively painless death by the sword.8 But by the

sixteenth century, Protestant discomfort with the supernatural

disallows such miraculous intervention, and thus the new Protestant

poetics of martyrdom drives forward the physical experience of pain,

emphasizing the centrality of suffering for the subject of martyrology.

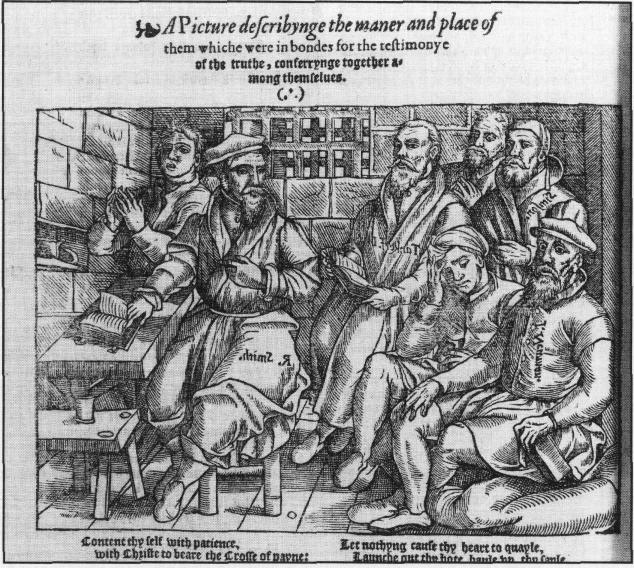

This is most evident in the gory death of Bishop Hooper, who burns very

slowly in an ill-lit fire (see figure 1):

In the which fire he

praied, with somwhat a loud voice: Lord Jesu have mercy upon me: Lorde

Jesu have mercy upon me. Lord Jesus receave my spirit. And they were

the last wordes he was herd to sound: but when he was blacke in the

mouth, and his tonge swollen, that he could not speake: yet his lippes

went, till they wer shrounke to the gommes: & he did knocke his

brest ith his handes untill one of his armes fel of, and then knocked

still with the other, what time the fat, water,and blond dropped out at

his fingers endes, until by renewing of the fire, his strength was

gonne, and his hand did cleave fast in knocking, to the yron upon his

brest, so immediately bowing forwarder, he yelded up his spirit. (1062)

Foxe directly compares Hooper's death with Polycarp's,

questioning who was more virtuous in his suffering, for

though

Policarpus, being set in the flame (as the story sayth) was kept by

miracle from the torment of the fyre, til he was stricken down with

weapon & so dispatched: yet Hoper by no less miracle armed with

patience, & servent spirite of Gods comfort, so quietly despised

the violence therof, as thoughe he had felt lyttle more then dyd

Policarpus in the fire flaming rounde about him.9

Foxe

implicitly attacks the early versions of martyrdom, emphasizing that

pain must be endured with patience, not erased, for martyrdom to be

spiritually valued. Hooper is not eased of his pain as is Polycarp; he

is given the strength to endure the suffering, "armed with patience,

& servent spirite of Gods comfort" in a way that is "no less a

miracle" than the fantastic interventions of Polycarp's death. It is

Hooper's great personal strength, augmented by God's grace, which makes

it seem "as though he had felt little more than did Polycarp."10 For

Foxe, the suffering of the body is the reality of martyrdom, a reality

which had in the past been clouded by the "famed additions of forged

miracles" of corrupt Catholic hagiographers; it is this personal

suffering that defines the acts of good men and gives authority to the

Protestant martyr.11

The extreme suffering of the martyr thus

becomes the condition of individualized and interiorized strength

manifested as "constancy," the central and oft repeated term used to

describe the Reformation martyr. This presents a problem for modern

historians of subjectivity, since it seems to defy the cultural

authority of spectacular punishment theorized by Michel Foucault as the

nexus of early modern social order.12 In a most disconcerting manner,

martyrdom inverts the Foucauldian model of disciplinary suffering; the

subject on the scaffold resists governing authority by translating

suffering from an effect of the subject's dissolution to that which

sanctions and empowers the subject, in opposition to the very governing

power which inflicts that suffering. And while the martyrological genre

does not debunk the disciplinary potential of the suffering body, the

importance of works such as Foxes calls for a revised examination of

the potential relationship between subjectivity and suffering.13 For

Foucault, the spectacle of the dismembered body defines the limits of

subjectivity, while martyrdom points to a different way of looking at

the relationship between suffering and subjectivity, as the tropes of

pain and violation are appropriated as constitutive to the subject.14

In

its resistance to Foucault's paradigm of early modern punishment, Foxes

text may seem a precursor of the bourgeois subject that emerges in the

eighteenth century when the individual invested with interiority and an

inner life becomes the privileged nexus of meaning. And while new

historicist and cultural materialist critics have argued that the

application of this model of interiority in the sixteenth century is

anachronistic, the excess of affect in Hooper's death expresses a form

of individualism that seems to resist the social, political, and even

ecclesiastical purposes of the text.15 And while this does not disable

the new historicist critique of the romanticization of subjectivity,

calling the concept of interiority illusory does not simply negate the

concept.16 Therefore I contend that for Foxe (and for much of early

modern culture) the interior truth of the subject becomes known through

pain which, as Hooper's death shows, emerges through an appropriately

theatrical expression of somatic violation. In essence, knowledge of

the subject's interiority emerges as the body is torn asunder.17 For

while Foxes work includes many martyrs who die without flinching, for

Hooper, Ridley, and a host of others, pain is not erased, nor is it

even mitigated by faith, as their screams for mercy attest.18 This is

not stoic fortitude, but real torment, experienced with savage

performativity. These key moments articulate a form of martyrdom and a

relationship between suffering and subjectivity quite distinct from

earlier medieval or later modern versions of martrydom, where the most

extreme suffering of the body marks not just the virtue but the

individualized essence of the subject.19

II. RAPE AND THE AUTHORITY OF WOMAN

But

what is the relationship between the articulation of an early modern

suffering subject and the gendering of that subject? Scholars have

begun to recognize the importance of gender in Protestant martyrology,

and arguably the most significant woman in English martyrology, both to

Elizabethans and to modern scholars, was Anne Askew, burned for heresy

in 1546.20 Askew's story, written by herself, was twice edited by the

two major arbiters of martyrology in Reformation England, first by John

Bale and then by Foxe, who reproduced Bale's edition (without Bale's

commentary) along with a detailed description of Askew's death. And

while Askew's narrative of her interrogation is primarily concerned

with the philosophical debate over central theological terms, as with

Foxes justification of Hales's suicide, an eroticized violence haunts

the margins of the text and emerges in the key dramatic details of her

narrative. In Askew's case her spectacular death is not the central

violence in her drama; for Askew, her suffering comes with her torture.

John King has asserted that Askew's account has particular power

because it is unusual in its exposure of "the full rigor of torture, an

unheard-of practice in Tudor England."21 Askew presents her torture on

the rack as being used not so much as a method for the discovery of

truth, but as an excessive, and extremely personal, act of violence.

She writes, with almost brutal austerity,

then they ded put me

on the racke, byause I confessed no ladyes nor gentyllwomen to be of my

opynyon, and theron they kepte me a longe tyme. And bycause I laye

styli and died not crye, my lorde Chauncellour and mastre Ryche, toke

peynes to racke me their owne handes, tyll I was nygh dead.22

Askew's

detail that her interrogators chose to torture her with "their owne

handes" implies that their excessive zealotry is driven by sadistic

pleasure. In his commentary on Askew's text, Bale explicates the scene

further:

A kynges hygh counseller, a Judge over lyfe and

deathe, yea, a lorde Chauncellour of a most noble realme, is now become

a most vyle slave for Antichrist, and a most cruell tormentoure.

Without al dyscressyon, honestye, or manhode, he casteth of hys gowne,

and taketh here Upon hym the most vyle offyce of a hangeman and pulleth

at the racke most vyllanouslye.23

This loss of "manhode"

suggests the traditional erotic formulation equating lack of control

with male heterosexual desire, and with rape in particular.24 Bale even

more directly than Askew equates Askew's torture with excessive desire,

thus emphasizing the moral weakness of Askew's persecutors. The writing

of the scene seizes the power from the torturers and places authority

with Askew, whose terse and controlled description is directly opposed

to her tormentors' loss of self-mastery. This authority and control as

a writer has made Askew particularly notable to scholars of early

modern culture, for not only does she defy the prohibitions on women's

speech but she also invests herself with the liberal ideals of

interiority, self-containment, and resistant self-justification; she

constructs herself as anachronistically modern.25

How, though,

does Askew's position within the larger genre of martyrology

participate in creating this "forum for [the] secularizing and

gendering [of] private identity"26 Frances Dolan has argued that while

women like Askew who were publicly executed in the early modern period

could gain authority to speak, the violence of execution carried

distinct erotic connotations: "the executioner would appear as a brutal

rapist, [and] the spectators as sadistic voyeurs." Therefore women

could maintain their authority to speak only as long as their "virtue .

. . [was] registered by means of their disembodiment."27 Indeed, as

Foxes defense of Hales shows, such a correspondence between

disciplinary violence and rape is vital to the writing of martyrdom.

The narratological formulation of rape in early modern culture, most

famously articulated in William Shakespeare's The Rape of Lucrece, was

more than a description of physical assault; rape was primarily about

an attempt at seduction (supported by a threat of force) which finally

fails as the narrative ends in violence.28 With this sort of structure,

rape becomes a potent metaphor for the theological struggle of the

martyr, as the very soul of the victim is assaulted-at first not

physically-but by tempting calls for the recantation of her heresy. And

in the rape narrative, as in martyrology, the final application of

physical violence spells an ironic victory for the victim, who defies

the physical threat of the violator with her eloquent resistance. And

as the victim (both of rape and martyrdom) rewrites the event (or is

written about), she/he is able to reconstruct her physical loss. So,

just as Lucrece defends her chastity and brings down the Tarquins's

rule by relating her story to her husband and his allies, it is through

the writing of her/his story that the martyr is able to maintain

her/his spiritual (if not physical) integrity even through the act of

violation and beyond her/his death.

I would suggest, then, (in

contrast to Dolan) that Askew's speech is not enabled because the

eroticization of her torture is suppressed, but that the perception of

her torture as rape authorizes her resistant voice. For while one may

not actually see Askew's torture, because of martyrology's reliance on

repeated spectacles of the suffering body, it is difficult not to

imagine her suffering at the lascivious hands of her tormentors. The

trope of martyrdom-as-rape demands that the fantasy of Askew's violated

body haunt her narrative; her sexualized body must remain at least

partially visible (while rigorously policed), emerging only at the

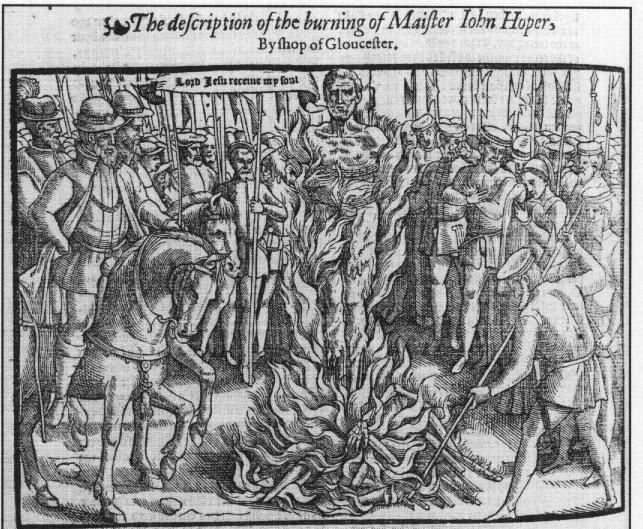

borders of the text. For example, the title page of her first

examination deploys, in bold print, verses from Proverbs 31: "Favoure

is desceytfull / and bewtye is a vayne thynge. But a woman that feareth

the lorde / is worthye to be praysed. She openeth her mouthe to wysdome

/ and in her language is the lawe of grace." So while it is clear that

a woman's potential sexuality, her "bewtye," must be contained by

"fear," it is also clear that if properly contained she may be

authorized to open her mouth "to wysdome," as Askew has done.29 This

productive tension between sexuality and its containment is manifested

in the representation of Askew's body on her title page (see figure 2).

Her body is composed and elegant; she stands almost as a Greek statue,

a classical model of Woman. She also prominently displays in her hands

a Bible tightly closed with clamps, visibly maintaining the physical

integrity of the Word just as she maintains the integrity of her body,

signifying her appropriately contained sexuality as described by the

quotation from Proverbs. Yet she is not sanitized of eroticism, and her

figure is still marked as both female and sexualized; her breasts are

clearly visible under her gown, and her hair threatens to burst out of

its containing ribbon. And the specter of erotic assault remains, for

partially concealed behind her skirt is the figure of a serpent adorned

with a leering papal head, denoting the insidious phallic force of the

persecution of the Antichrist that threatens to slither up her dress at

any moment. Here the iconic power of Woman, developed from highly

conservative discourses of patriarchal control of the female body,

becomes applicable not just to the idealized bodies of fantasy women,

but becomes accessible to women as a strategic move in the theological

and political debates of the Reformation.30 These women are able to

speak in an authorized voice, sanctioned by their eloquent textual

defense of their bodies, both physical and spiritual, which Askew

exploits to produce a sanctioned space for her own narrative.

III. SODOMY

Askew's

radical speaking voice shows how the feminized structure of resistant

suffering has an exceptional authority as a model of subjectivity, to

such an extent that it becomes part of the overarching generic formula

of Protestant martyrology. As Megan Matchinske has pointed out, the

Protestant martyrological subject that "will . . . become synonymous

with later Reformation paradigms for both men and women finds at least

one of its early voices in an institutionally framed definition of

acceptable, reformist, female exegesis."31 Bales introduction to

Askew's first examination compares her to Blandina, a central martyr of

the early church, as the "mother of martyrs... for her Christen

constancye," and so as a protomartyr for the entire Protestant martyr

tradition.32 One can see the gendered dynamic of male assault and

female defense developed in Askew's narrative repeated throughout Foxe;

its seduction leading to rape structure eerily parallels the repeated

struggle between the Catholic examiner and the soon to be martyr, which

John Knott has called the standard "script" of Protestant

martyrology.33 In a sense, all martyrs that follow Askew, the "mother

of martyrs," must utilize the specifically female tropes developed in

her protomartyrdom.

Most martyrs, though, were not women. So

while the erotic narrative of rape becomes most visible when women

become the objects of sexual violence, its form persists even as men

become the objects of that violence, disrupting the normative hierarchy

of male mastery defined by masculine penetration of women. Yet male

martyrs do not simply become women-in an early preface to Actes and

Monuments Foxe sets forth martyrs as "the true Conquerers of the world,

at whose hand we learne true manhoode"("The Utility of this History,"

22r). Certainly, as early modern England was a highly patriarchal

culture, the valorized injury of the martyr must be reserved for the

male body in order to secure the authority of martyrdom for men. And

thus the writing of male martyrs demands that the hierarchical violence

of rape be translated from the female body to the male body, a complex

shift which creates martyrdom as an overdetermined site for the

contradictory impulses of horror, pleasure, and devotion that circulate

around male homoeroticism in early modern culture.

In a certain

sense, the male subject of martyrdom is written in a manner parallel to

the defensive structure of the female martyr; throughout Actes and

Monuments the specter of sexual assault haunts male martyrs' suffering

just it does for women martyrs. This becomes most clear in episodes

involving Bishop Bonner, whose assaults upon the bodies of innocent men

and boys are elucidated as peculiarly excessive and are laced with

erotic tropes. In Bonner's examination of Thomas Tomkins in 1555, the

specter of erotic violence is rendered in terms distinctly parallel to

Askew's torture. Foxe shows Bonner's interest in Tomkins to be in

excess of his religious mission of conversion; Bonner takes an

inexplicably personal interest in Tomkin's torments just as Askew's

tormentors take with her: "Doct. Boner B. of London kept the sayd

Tomkins with hym in prison halfe a yeare. Duryng which tyme the sayd

Bishop was so rigorous unto hym"; Bonner "beat hym bitterly about the

face, whereby his face was swelled," and "tooke Tomkins by the fingers,

and held his hand directly over the flame, . . till the vaines shronke,

and the sinewes [burst]."34 And most significantly, before beginning

this torture Bonner "caused [Tomkins] beard to be shaven," which enacts

a powerfully eroticized degradation of the male subject to an

erotically subordinated position. The victim is stripped of his marker

of patriarchal authority and is rendered a potential object of male

sexual desire, not as a feminized figure but as a boy.35 Due to its

associations with classical precedence and its understood practice

amongst the elite and educated (and thus relatively protected) classes,

pederasty was one of the few visible forms of homoeroticism in early

modern culture.36 Yet even those most invested in such classical models

had limited tolerance for pedophilia, not because it eroticized male

relationships, but because the power dynamics of the relationship were

(ironically) too much like those between men with women.37 Michel de

Montaigne expresses this anxiety in his essay "On Friendship," where he

condemns the "Greek license" as an excessive and uncontrolled desire,

as a "furie" or "insolent and passionate violences" analogous to the

disruptive violence of heterosexual rape, thus paralleling Bonner's

pedophilia to the unrestrained desire exhibited by Askew's torturers.38

|

|

|

|

Foxe

can thus be seen as caricaturing Bonner as manifesting a recognizably

disruptive form of homoerotic desire. A demonized, and particularly

Catholic, excess of desire thus becomes visible not just upon the

bodies of women, but upon the bodies of men as well. Foxe develops

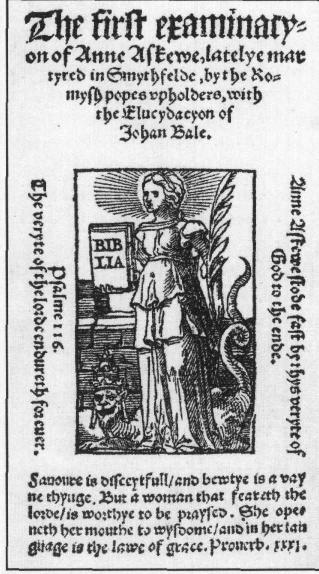

Bonner's passions most famously in the text of Actes and Monuments that

surrounds the sensational woodcut "The Ryght Picture and True

Counterfyt of Boner, and his Crueltye, in Scourgynge of Goddes Saynctes

in his Orchard" (1689) (see figure 3). On the page below the woodcut

Foxe includes a short poem describing Bonner as a grotesque figure of

unnatural excess, declaring "natures woorke / is thus deformed now" in

Bonner, for he is a "Cannibal" with "belly lowen and head so swolne"

(1689).39 His corpulent belly, the poet declares, arises from his

unnatural appetite, for "it should appeare that blood feedes fat," and

that his "belly waxt with blood."40 Foxe follows this poem with

elaborate descriptions of Bonner's excessively violent "scourgynge[s]"

of young men and boys, analogous to his assault on Tomkins. Foxe tells

of Thomas Hinshaw, who Bonner had

knele against a long bench in

an arbour in his garden, where the said Thomas with out any enforcement

of his part, offred hymselfe to the beating, and did abide the fury of

the said Boner, so long as the fat panched bishop could endure with

breath, and till for wearinesse he was faine to cease, and geve place

to his shamefull act. (1691)

Bonner's beating of Hinshaw "till

for wearinesse he was fame to cease" mirrors a failure of

self-governance by Askew's interrogators, and suggests the exhaustion

of erotic expenditure. Foxe also tells the similar story of John Miles,

who Bonner "had ... incontinentlye to his Orchard" where he likewise

"skewed his cruelty upon him" (1650). And while there is no direct

declaration of Bonner's erotic desire, the OED gives a

fifteenth-century definition of "incontinentlye" as "wanting in self

restraint, chiefly with reference to sexual appetite," clarifying what

is "shamefull" about these acts." Foxes rendition of Bonner's desires

becomes more apparent in the woodcut's "ryght Picture and true

counterfeyt of Boner," which extends the erotic implications of

scourging well beyond what the text suggests.42 The male figure

suffering under Bonner's attentions is not just "knele[ing]," as the

text describes Hinshaw, but is on his hands and knees, and bares not

his back to be scourged, but his backside. Bonner is positioned

strategically behind his exposed victim with his codpiece notably

swollen beneath his engorged belly. The woodcut's powerful suggestion

of anal penetration, combined with the accretion of erotic implications

in the accompanying text, produces a quite distinct image of Bonner as

a violent sexual predator.

Foxe extends his description of

Bonner's excesses further in a story he recalls, "although it touche no

matter of religion, yet because it toucheth somthyge the nature and

disposition of that man" (1691). Foxe describes that while traveling

the Thames on a barge, Bonner and his chaplains "espyed a sort of yong

boyes swimming and washing themselves" (1691). Attracted to this scene,

Bonner seductively approaches the boys with "verye gentle language, and

fayre speache, untyl he had set his men a land" (1691). Then Bonner has

the men violently assault the boys, "beatyng some with nettels, drawing

some throw bushes of nettels naked" (1691), all as Bonner watches. The

very senselessness of this scene, with no theological or political

implications, but only insinuations of some corruption of "nature and

disposition," is the nadir of Foxes degradation of Bonner. The Catholic

persecution of the true church is reduced by its connection to the

"democratizing implications of lust and pain" that Debora Shuger sees

circulating in the early modern construction of the suffering

individual. As Shuger quotes Lear, "thou rascal beadle, hold thy bloody

hand! / Why dost though lash that whore? Strip thy own back. / Thou

hotly lusts to use her in that kind / For which thou whipp'st her."43

For Lear, sexual desire becomes directly connected to suffering as that

which the subject defines her/himself against. Desire and suffering

together are the obscene and disruptive forces that must be resisted,

and Bonner, with his grotesque desires and deformed body with its

"belly lowen and head so swolne," becomes the transgressive and

carnivalesque form against which the classically contained subject of

martyrdom may be differentiated.44

This phobic deployment of

homoeroticism in Protestant martyrology is part of the legacy of

reformist anti-Catholic propaganda that equates Catholicism with

homoerotic transgression. Bale's work is notorious for his use of this

strategy, as when in his Acts of English Votaries Bale "takes some

popular and apparently innocuous stories (such as Gregory I's comments

on the beauty of English slave boys) and creates a sodomitical

subtext."45 Bale particularly focused on the homosocial space of the

monastery, which he made a synonym for homoerotic excess. As he

extravagantly accuses Catholic votaries, we see nothing in you but

haughtiness, vainglory, covetousness, pride, hatred, malice,

manslaughter, banquetings, gluttony, drunkenness, sloth, sedition,

idolatry, witch-craft, fornication, lechery, lewdness, besides your

filthy feats in the dark when women are not ready at hand.46

In

his commentary on Askew's examinations, Bale equates the Catholic

Church with "a spirytualte, called Sodome and Egypte [where votaries]

rejoyce in myschefes amonge themselves."47 This vague, sexualized

transgression that is isolated and hidden, this idea of "myschefes

among themselves," was a particularly potent weapon against monastic

orders, and it was quite likely that the politics surrounding the

dissolution of the monasteries motivated the development of antisodomy

laws in the 1530s.48

IV. FRIENDSHIP

This specific

demonization of sodomy, though, is not equivalent to modern homophobia;

recent scholarship has shown that there was no coherent discourse of

homoeroticism in early modern England, and so no single form of

homosexuality, or even the understanding of sexuality as a formative

aspect of subjectivity.49 "Sodomy" (or the "sodomite" as an entity), as

the closest contemporary term, existed as an only vague, surreal

horror; like Bale's "myschefes among themselves," sodomy was not even

identified with a specific set of sexual acts and could be associated

with any act that did not support procreation. Sodomy was not even

limited to the body-it could incorporate any subversive behavior such

as treason or heresy; it was "a seditious behavior that knew no

limit."50 Yet the very perception of sodomy as a limitless

transgression opened a space for differentiated articulations of

desire, as the excessive horror attached to the specter of sodomy

precluded any sort of self-identification as a sodomite.51 Accordingly,

there were a wide variety of erotic formulations that could exist

simultaneously with sodomy, without their mutual continuity being

recognized. Thus the deployment of sodomy in Protestant martyrology

does not exclude the text's enactment of authorized forms of

homoeroticism.

|

|

As

Alan Bray has pointed out, the prohibited forms of homoeroticism that

fell under the rubric of sodomy were often functionally

indistinguishable from the eroticized discourse of male friendship

which was vital to the structures of politics and patronage in early

modern culture.52 Eroticized relationships between men were key to the

coherence of alliances, particularly as they were articulated in a

language of physical and spiritual intimacy that was not exclusively

platonic, but dependent upon a distinctly physical intimacy both in its

rhetoric and in actuality. This intimacy constituted a sanctioned

homoeroticism formulated (though not consciously) against the

disruptive, antisocial eroticism that composed sodomy.53 Of course, as

Mario DiGangi points out, "just because the discourse of male

friendship allowed a place for homoerotic desire does not mean that all

friendships were necessarily homoerotic." DiGangi goes on to point out

that the discourse of friendship reveals

a multiplicity of

possible social configurations, erotic investments, and sexual acts:

this multiplicity cannot be reduced to a uniform system of behavior. .

. .[But] it is nevertheless the case that early modern gender ideology

integrated orderly homoeroticism into friendship more seamlessly than

modern ideological formations, which more crisply distinguish

homoeroticism from friendship, sexual desire from social desire.54

There

was, then, a noteworthy opening within the relationships between men

that enabled particular forms of eroticism to emerge and generate

powerful affective relationships between men, opposed to (or at least

not recognized as) the disorderly desires of sodomy. So, within this

incoherent network of contrasting forms of homoeroticism, martyrdom's

eroticized suffering could be simultaneously equated both with sodomy,

which was to be resisted with abject horror, and the eroticized

intimacy of friendship, which was to be embraced as a constitutive

element of privileged male subjectivity.

A key distinction

between the erotics of sodomy and those of friendship was that, unlike

the "passionate violences" of the "Greeke license," the participants in

idealized friendship had a balanced and symmetrical exchange of desire.

As Jeffrey Masten argues, friendship was to be based in an "erotics of

similitude" where "gentlemen friends are identically constituted." So,

even while pederasty was condemned, the ideology of friendship

"valorizes another, interpenetrating version of sex between men."55 The

structure of martyrdom, though, was not one of symmetry or equality;

the related formulas of rape and sodomy are objectionable precisely

because they are hierarchical. But still, a desire to suffer this sort

of sexual violation was the primary drive of martyrdom; as Foxe put it,

martyrs were valorized for "offer[ing] their bodies willinglye" to the

"rough handling of their Tormentours" (23v), just as Hinshaw offered

himself willingly to Bonner's erotic attentions. This is the paradox

Dolan's work gestures toward; that is, that despite the erotic

significance surrounding public execution, male bodies were still

rendered visible objects of sexual violence on the scaffold. Because of

this, I argue, the eroticized violence of public execution does not

necessarily follow an exclusively heterosexual logic of active male

penetration and passive female penetrability. And so, in the spectacle

of the penetrated male body there is a potential for an erotic economy

that disrupts heteronormative gender hierarchy.56

This erotic

structure is particularly evoked in early modern devotional writings;

as Richard Rambuss has pointed out, in the poetic formulation of

devotion to the body of Christ in the works of writers such as Richard

Crashaw, John Donne, and George Herbert, erotic desire is powerfully

writ in the spectacle of the suffering male body. In these works

an

orifice or perforation in the body becomes the portal for devotional

access to Jesus: one thus enters him or is entered by him, and Christ

and Christian together are deluged in the salvific streams that from

the penetrated body. . . The position of ravisher and ravished,

penetrator and penetrated, can variously and successively be taken on

by male, female, and undecidably gendered devotional bodies as they are

rendered ecstatically expressive, devotionally stimulated.57

And

thus the generic structure of martyrology produces a homosocial/

homoerotic continuum that manages to evade the dangerous asymmetry that

might elicit the specters of sodomy and rape, while still maintaining

the hierarchical opposition that invests the martyr with his erotic

power as victim. Martyrs all share the same position in relation to

power-they are all simultaneously subjected to authority as the objects

of erotic violence, and so are "identically constituted" as male

friends, even as they take upon their bodies the eroticized penetration

of their persecutors. And so in Actes and Monuments the potential for a

counterheteronormative desire emerging from suffering allows martyrdom

to represent both the hierarchical violence of rape/sodomy and a

virtuous, yet still erotically charged, desire of symmetrical exchange.

It is together that martyrs suffer violation, and this violation is

their bond.

The desire for suffering fundamental to martyrology

manifests itself most evidently in Foxes writing of Thomas Bilney's

final evenings in prison. Bilney was one of the early Cambridge

reformers who had converted Hugh Latimer, and who had been a profound

influence on Matthew Parker. But he had become a problematic figure for

later reformers, and so Foxe, possibly to divert attention from more

unsettling issues, focuses on a particularly dramatic moment from just

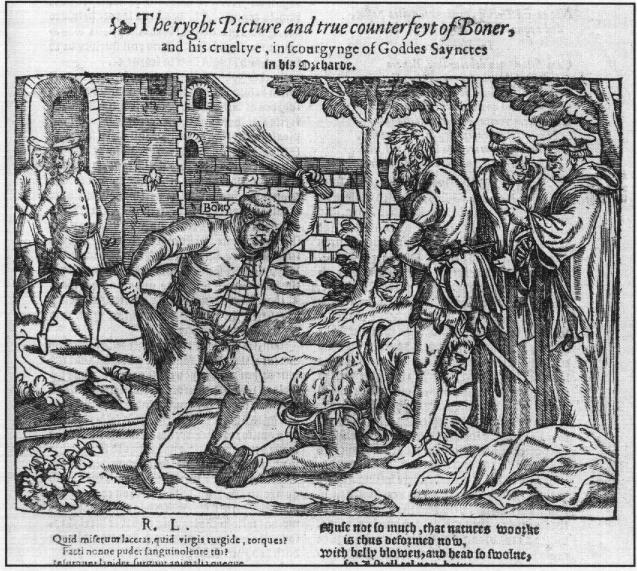

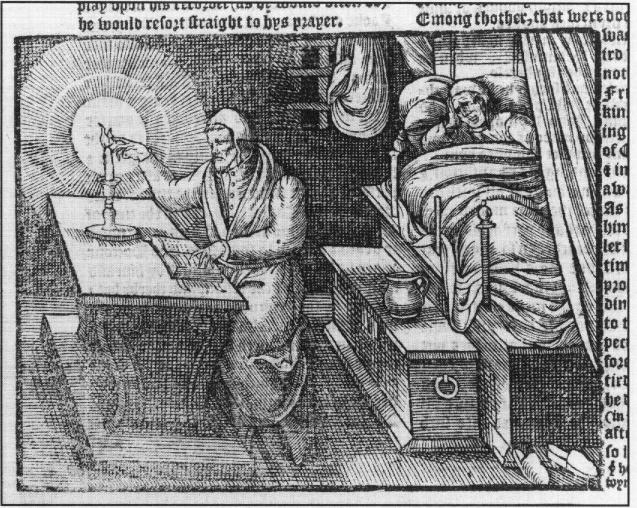

before his death.58 In this episode, Foxe conceives of Bilney's

suffering not simply as a passive act of tolerance or resistance;

Bilney actively seeks out suffering, and even becomes his own

tormentor. As Foxe reports, Bilney "would manye times attempte to prove

the fire [by] holding his finger nye to the candle" (467). What is

significant about this scene is not just the religious zealousness it

expresses, but that Bilney is engaged in this martyrdom-in-- miniature

in the intimate space of his bedchamber, and with a very intimate

audience. For while Bilney was in prison, two church scholars had been

sent to try and draw him back to orthodoxy; yet while they "lay with

him in prison in disputation" it is not Bilney who is drawn back into

the fold but it is one of the doctors who is seduced to Bilney's

nonconformist beliefs: "Doct. Call by [the] worde of God through t'

holy ghost, and by Maister Bilneyes doctrine and godley life whereof he

had experience, was converted to Christ" (467). And in the woodcut that

accompanies the scene, it is the newly converted Dr. Call who is

looking on from the bed (with some curiosity) as Bilney burns his

finger; "said the doctor that lay with him, what do you master Bylney?

He answered nothing but trying my flesh by Gods grace, and burninge one

ioynt" (467, see figure 4). That the doctor "lay" with Bilney does not

demand, of course, that they be represented as physically "lying"

together; in the sixteenth century the word could signify "discussion"

or "intellectual debate." Yet to "lie" also had (and still has) sexual

connotation, and the woodcut does represent Bilney's and Call's

relationship in a way that suggests physical intimacy. Bilney and Call

are shown to be bedmates in their shared cell, their intimacy

emphasized by the curtain hung hastily over the barred window, as well

as the presence of domestic accoutrements like a pair of slippers and a

washing pitcher scattered around the room. This sort of physical

intimacy was a particularly important element of the institution of

male companionship as it is constructed in the writings of Montaigne,

Francis Bacon, Richard Braithwait, and others. As John Lyly describes

the intimate friendship of Euphues and Philautus,

they used not

only one board but one bed, one book (if so be it they thought not one

too many). Their friendship augmented every day, insomuch that the one

could not refrain the company of the other one minute. All things went

in common between them, which all men accounted commendable.59

Foxes

representational choice thus exposes the interplay between the

suffering of martyrdom (which Foxe has invested with such erotic

potential) and the physical intimacy of early modern male friendship.

The

self-inflicted nature of Bilney's suffering also has powerful erotic

resonance in early modern religious discourse. Self-torture echoes the

practice of scourging the flesh in flagellation, common in private

devotions of the early modern period. But by the sixteenth and early

seventeenth century in Protestant Europe, flagellation was becoming

associated with autoerotic pleasure; in a German medical treatise of

1629, flagellation is shown to act as a sexual stimulant, especially

for men. "That there are Persons who are stimulated to Venery by

Strokes of Rods, and worked Up into a Flame of Lust by Blows and that

the Part, which distinguishes us to be Men, should be raised by the

Charm of invigorating Lashes.1160 And in late sixteenthcentury English

anti-Catholic writing, flagellation was often seen as a suspect

solitary pleasure; in his undercover expose of supposedly debauched

practices in the seminary for exiled English Catholics in Rome, Anthony

Munday focuses on the elaborate physical penance performed by the

residence. Munday describes how one of his compatriots tries to seduce

him to the physical pleasures of selfflagellation:

he willed me

to trie it once, and I shoulde not finde any paine in it, but rather a

pleasure. For (quod he) if Christe had his fleshe rent and tome with

whips, his handes and feet nayled to the Crosse, his precious side

gored with a Launce, his head so pricked with a Crowne of thorne, that

his deere blood ran tilling downe his face, and all this was for you:

why should you feare to put your body to any torment, to recompence him

that hath done so much for you?61

This sort of anti-Catholic

propaganda may have influenced Foxe to alter his version of Bilney's

prison experience, for by the 1583 edition of Actes and Monuments

Bilney's act of self-torture has been moved out of the bedchamber and

into a public space. Bilney is no longer testing the flames before his

lone bedmate but while "sitting with his ... friendes in godly talke,"

and is making his display as part of a public pedagogical act, where

the listeners "tooke such sweete fruite therin, that thy caused the

whole sayd sentence to be fayre written in Tables, & some in theyr

bookes."62 It is possible that the erotic valences of Bilney's

self-burning became too easily identifiable with the erotics of

Catholic self-flagellation, and so it had to be placed in a communal

setting, with multiple witnesses to legitimate the wholesome intention

of the act.63

|

|

But

in the 1563 edition, the erotics of suffering made visible in the image

of Bilney and Call's male friendship translates the demonized desires

of Catholic violence to an erotics of virtuous nonconformist suffering.

In the exchange between Bilney and Call, the physical intimacy of male

friendship inherent to the bedchamber has been transferred to the

spectacle of suffering, which, (following Rambuss's reading of

devotional poetry) has a significant affective power to conjoin the

devotional writer with the divine. The erotic language surrounding the

wounded body thus operates as a "technology of affect," to borrow Lisa

Jardine's term. Like the Erasmian epistolary rhetoric of intimacy

analyzed by Jardine, the rhetorical construction of suffering acts to

"convey passionate feelings, [and so] to create bonds of friendship"

among martyrs."This technology of affect is, as Jardine says, what

stands in for physical proximity, reproducing the physical intimacy

vital to male friendship; it is this intimacy that is generated in

Bilney and Call's cell. Bilney is not in direct physical contact with

Call, for he has left their mutual bed; but as Bilney lays his finger

to the flame, the virtuous martyr to be and his new convert are unified

not through direct physical union, but through the affective power of

Bilney's spectacular suffering.

The primary significance of

this eroticized structure of martyrology is that, like the bond of

friendship, it is a productive force. Male friendship was not simply an

emotional intimacy between men, but was, as Masten points out,

"constitutive of power relations in the [early modern] period," so much

so that the emergent model of companionate marriage, with its emphasis

on reproduction, was articulated in terms coterminous with the

structures of male friendship.65 In martyrdom, this logic of generative

friendship is deployed in support of the apostolic agenda of the

Protestant church. This is evident in one of the most famous moments in

Actes and Monuments, the communal death of Bishop Ridley and Father

Latimer. As they are brought to the stake, Foxe constructs an almost

romantic moment between the two men; as Ridley sees Latimer "with a

wonderous cheerful) looke, [he] ranne to hym, embraced, and kissed

hym." Together they go to the place of their burning and, as many

martyrs before and after, kiss the stake and pray. And "after they

arose, the one talked with the other a little whyle.... What they said,

I can learn of no man" (1769). And while this moment of martyrdom is

not as clearly invested with erotic implications as Hinshaw's scourging

or Bilney's bedchamber, it is the presence of the stake on which they

will suffer (Ridley most spectacularly) that centers the scene, both

producing and validating their intimacy. The moment thus becomes a

cooperative generation of transcendental truth, dramatically

articulated in the apostolic force of martyrdom's spectacle. As Latimer

declares at the stake to Ridley, "be of good comfort maister Ridley,

and play the man: wee shall this day light such a candle by Gods grace

in England, as (I trust) shall never be put out."66 The spectacle of

Ridley and Latimer's deaths thus transforms the fire of martyrdom into

the flame of truth, the truth of the Reformed church. And whereas the

rape narrative is gendered female, this production of truth is

explicitly gendered male by Latimer's heroic call to his partner in

suffering to "play the man." And, paralleling the logic of male

friendship, this manly suffering is not a singular suffering; it is a

collective masculine suffering, a suffering of the "we" who have the

power to "light such a candle." It is a masculine communion of martyrs

that shall produce truth, a masculine communion absolutely contingent

upon the leveling force of the eroticized "rough handling" of

tyranny.67

This apostolic homosocial intimacy reverberates

throughout Foxes text, propped against the tyrannical violence of papal

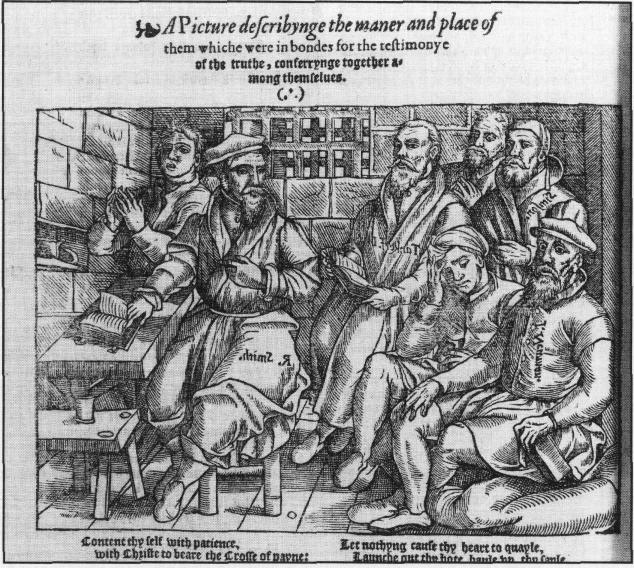

sodomy. This becomes clearly manifested in Foxes egalitarian fantasy of

spontaneous all-male Protestant communities being established in

English prisons during Mary's reign. Robert Smith's Newgate community

is a particularly good example of this male intimacy, where "caste in

an outwarde house wythin Newgate" (1260) the soon to be martyrs have

"Godlye conference within themselves with dayly prayinge and publyke

readynge, whiche they to theyr greate coumforte used in that house

together" (1260). This ad-hoc monastery has its own woodcut

illustration, where seven male figures are clustered intimately in a

sparsely furnished room, tightly closed in by walls (see figure 5).

This community is laced with intimate erotic valences as the figures

are positioned so closely that the two men in the bottom right corner

seem to have their legs intertwined, with the man in the right of the

frame having his hand placed delicately on the other man's left knee.

Thus the very male intimacy that generated Protestant suspicion of

sexual "myschife" in Catholic monasteries is not only maintained, but

is praised as an ideal form for a virtuous reformed church. It is clear

that for Smith's congregation, the antisodomy propaganda of Bale and

others does not disrupt the practical deployment of affective intimacy

between men in the establishment of the true church.

V. "RAVISHED WITH ZEALE"-THE THEATRE OF MARTYRS

So,

as Smith's gathering in Newgate shows, the technology of affect

produced in the eroticized spectacle of suffering is a powerful

mechanism for constituting the intimate homosocial communities of the

reformed church. How, though, does this mechanism operate in the

spectacle of the martyr suffering alone, as many martyrs do, without a

community formed around them? How does a death like that of Bishop

Hooper fit into this matrix of intimacy modeled by Ridley and Latimer

or the Newgate congregation? I contend that the power of the spectacle

of suffering to produce alliance is not limited to the formulation of

relationships within the narrative. A martyrology's function, and not

just for Foxe, is an evangelistic one, it is not simply to construct an

ideological figuration of subjectivity. The story of the martyrs'

suffering is designed to testify to the true faith and advocates its

adoption; it is thus crucial to Foxes project that his text itself

inspires imitation beyond itself. Foxe describes his project as

didactic, where the reader is to learn "not onelye what in those dayes

was done, but also what ought nowe to be followed" ("The Utility of

this History," 22r). As Foxe writes, after witnessing martyrs offer up

their bodies "to the rough handling of their tormentors ... is it so

great a matter then for our part, to mortifie our flesh?" ("The Utility

of this History," 22r). Martyrs are to inspire imitation, to make more

martyrs. This is the primary role of a martyrdom like Hooper's, where

the affective power of his dramatic suffering is not targeted to an

audience within the text, but is designed to reach out to the reader

through its dramatic power and draw them to the true faith of the

reformed church.

|

|

The

text is designed to stimulate such action not through rational

argument, but through the affective power of witnessing the spectacle

of suffering that gains its affective power over the audience (that is,

the reader) by means of its theatrical presentation.66 It is, of

course, commonly known that early modern nonconformist ethos included a

profound suspicion of the theatre. But as Ritchie Kendall has argued,

despite the stated antipathy to dramatic forms, "drama touched the raw

nerve of noncomformity," and theatricality acted as a primary mechanism

for representing the power of individuated nonconformist struggle for

faith.69 The Puritan passion for martyrology is a powerful testament to

this argument, for the performance of martyrdom is, in its essence,

dramatic.70 And Foxe, like other nonconformist writers, emphasizes the

dramatic elements of the form, portraying highly dramatic

interrogations (often in dialogue form) and laying out the martyrs'

performances on the scaffold for maximum dramatic effect.71

Even

though "the works of the nonconformist spirit almost invariably stop

short of the stage," the affective power of theatrical representation

to act upon its audience, even in written form, is not disabled.72 And

puritan writers conceived of that power as an erotic force, a demonic,

invasive threat that violates the very souls of the witness. John

Northbrooke stated that "I am persuaded that Satan hath not a more

speedie way and fitter schoole to work and teach his desire, to bring

men and women into his snare of concupiscence and filthie lustes of

wicked whoredome, that those places and playses, and theaters are."73

And William Prynne declared "[s]tage-Playes devirginate unmarried

persons, especially beautifull, tender Virgins who resort unto them."74

Theatre itself is conceived of as a potential rapist, able to force

itself upon the victim and coerce him/her to erotic acts. Laura Levine

points out that antitheatrical writers saw theater, in its classical

origins, as a mechanism for making women vulnerable to men, and so

"theater [was] founded on and in rape." For Levine, "theater itself

comes to be synonymous with its origins, for pamphleteers conceive of

it as a kind of rape of the mind, a'ravishing' of the senses."75

And

so, for Foxe and his fellow Protestants, the theatricality of

martyrological narrative mimics the violence exercised by the

tormentors themselves; as the Catholic persecutors exercise their

unnatural desires upon the bodies of the martyrs, in turn the

horrifying spectacle of the martyrs' torment ravish the audience. But

as with the shift from Catholic sodomy to virtuous homoerotic

friendship, this erotic violence becomes, for reformist writers, a

righteous eroticism. Affective erotic power is transferred from the

satanic and disorderly to the didactic and evangelistic, creating and

expanding the nascent "elect nation" of English Protestantism.76 In the

schema of martyrological representation, then, it is not necessary to

actually suffer physical violence to become ensconced in the erotics of

martyrdom-one simply must be part of the audience of martyrdom. And so

the logic of Hooper's dramatic death becomes clearer, for it is

structured to enclose the reader in the moment. In the horrifyingly

explicit woodcut, Hooper does not look up to the divine, nor does he

look to other figures in the frame. His direct stare meets the reader's

gaze with firm conviction. His suffering reaches out to ravish the

reader's senses with the sublime display of wounds and draw her/him

into his suffering. As Foxes contemporary Meredith Hanmer writes, in

his introduction to his 1577 translation of Eusebius church history,

If

we stande upon the Theater of Martyrs, and there behold the valiant

wrastlers, and invincible champions of Christ lesu, how can we chuse

but be ravished with Zeale when we see the professors of truth torn in

peeces by wilde beastes, crucified, beheaded, stoned, stifled, beaten

to death with cudgels.77

Here the martyrological text takes the

place of the persecutor, and the reader becomes the ravished victim.

The theatrical spectacle renders the spectator (or the reader)

powerless before it, and so the dramatic writing of martyrdom

reproduces within the reading subject the very ravishment it displays,

extending the desires of the text beyond its own bounds and into the

souls of its audience.

Auburn University

| [Footnote] |

| An

earlier version of this essay was presented at "John Foxe and His

World; An Interdisciplinary Colloquium," held at the Ohio State

University in April 1999. 1 would like to thank Megan Matchinske, Chris

Frilingos, and Hilary E. Wyss for their insightful readings and patient

suggestions. |

|

| 1

John Foxe, Actes and Monuments (London, 1563), 1116. Hereafter cited

parenthetically by page number. All citations are from the 1563

editions unless otherwise specified. |

| 2

M. Dalton, The Country Justice (London, 1626), 234, quoted in Michael

MacDonald and Terence Murphy, Sleepless Souls: Suicide in Early Modern

England (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1990), 15, 62, 63. MacDonald and

Murphy assert that while there was a formal abhorrence of suicide in

medieval culture as well as in the eighteenth century,

sixteenth-century England saw a particularly severe enforcement of

suicide as both a religious and secular crime. The difficult Foxe has

defending Hales becomes evident with the disappearance of Hales from

Actes and Monuments by the 1583 edition. |

|

| 3

John Hooper, in his "A Brief Treaties Respecting Judge Hales," places

the responsibility for Hales's suicide on his recantation, which,

Hooper contends, left Hales vulnerable to satanic influence, as a

"new-made Christ is not able to keep the devil away" (in The Later

Writings of John Hooper, ed. C. Nevinson, Parker Society [Cambridge:

Cambridge Univ. Press, 1852], 374), quoted in MacDonald and Murphy, 62.

Although he does note the stress caused by Hales's jailers'

psychological harassment, Foxe does not foreground the argument that

Hales was non compos mentis at the time of his death. |

| 4

John Donne makes visible the precarious connection between martyrdom

and suicide as he cites multiple early church martyrs who become

"enforcers of their owne Martyrdome" to support his paradoxical defense

of suicide (Biathanatos [New York: Fasimile Text Society, 1930], 64). |

| 5

Christopher Marlowe also adapted this story in act 4 of 11 Tamburlain

the Great, in Doctor Faustus and Other Plays, ed. David Bevington and

Eric Rasmussen (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1995). |

|

| 6

Alan Bray delineates the conflation of friendship and sodomy in his

"Homosexuality and the Signs of Male Friendship in Elizabethan

England," in Queering the Renaissance, ed. Jonathan Goldberg (Durham:

Duke Univ. Press, 1994), 40-61. Many scholars have expanded upon his

work, most eloquently Jeffrey Masten in Textual Intercourse:

Collaboration, Authorship, and Sexualities in Renaissance Drama

(Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1997). By engaging with male-male

erotic relationships as discursively distinct from male-female

relationships, my argument follows the work of these scholars, as well

as Valerie Traub's call to recognize that "gender, sexuality, and

subjectivity are separate but intersecting discourses" (Desire and

Anxiety: Circulations of Sexuality in Shakespearean Drama [New York:

Routledge, 1992, 102). Yet I also contend that recognizing the

structural continuities between early modern heteroerotic and

homoerotic economies of desire is crucial to understanding the

circulation of sexuality in Protestant martyrology. |

|

| 7

See John R. Knott, Discourses of Martyrdom in English Literature

1563-1694 (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1993); and Helen C. White,

Tudor Books of Martyrs (Madison: Univ. of Wisconsin Press, 1963). |

| 8 The Auncient Ecclesiasticall

Histories of the First Six Hundred Yeares

After Christ, trans. Meredith Hanmer (London, 1577), 65-68. |

| 9 Foxe adds this comparison between

Hooper and Eusebius in the 1583

edition (1502). The description of Hooper's death remains fundamentally

unchanged between the editions. |

| 10 My emphasis. |

|

| 11 This quotation is from the 1583

edition describing the death of

Clement, about whom Foxe says "forasmuch as I finde of his Martyrdome

no firme relation in the auncient authors, but onely in such new

wirters of latter tyres, which are wont to painte out the lives and

histores of good men, with famed additions of forged miracles, therfore

I count the same of lesse credite, as I do also certaine Decretail

Epistles, untruely (as may seeme) ascribed and intituled to his name"

(38). |

| 12 Michel Foucault,

Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan

(New York: Random House, 1979). Foucault briefly discusses the

instability of public execution, primarily in terms of its popular

festive potential; he argues that "in these executions, which ought to

show only the terrorizing power of the prince, there was a whole aspect

of the carnival, in which rules were inverted, authority mocked and

criminals transformed into heroes" (61). For discussions of the

troubles surrounding the scaffold, see Thomas Laqueur's "Crowds,

Carnival and the State in English Executions, 1604-1868," in The First

Modern Society: Essays in English History in Honour of Lawrence Stone,

ed. A. L. Beier, David Cannadine, and James M. Rosenheim (Cambridge:

Cambridge Univ. Press, 1989), 305-55; Peter Linebaugh, "The Tyburn Riot

against the Surgeons," in Albion's Fatal Tree: Crime and Society in

Eighteenth-Century England, ed. Douglas Hay, Peter Linebaugh, John G.

Rule, E. P. Thompson, and Cal Winslow (New York: Pantheon, 1975),

65117. |

|

| 13

Janel Mueller's "Pain, Persecution, and the Construction of Selfhood in

Foxes Actes and Monunwnts" offers a useful reading of Foxes uses of the

body in pain, emphasizing the importance of the suffering subject to

early modern theology. But she sees the structures of martyrdom as

offering a "decisive challenge to reading the early modern body as a

locus of sexualized pleasure" (Religion and Culture in Renaissance

England, ed. Claire McEachern and Debora Shuger [Cambridge: Cambridge

Univ. Press], 162). I contend, following Richard Rambuss, that

representations of suffering do not necessarily exclude eroticism; see

his response to Caroline Walker Bynum in Closet Devotions (Durham: Duke

Univ. Press, 1998), 42-49. |

|

| 14 The

perception of pain as an element that only acts negatively against the

subject recurs in Elaine Scarry's The Body in Pain: The Making and

Unmaking of the World (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1985). Scarry

focuses primarily on torture, which limits the scope of her

investigation; she does not investigate other cultural fields (from

martyrdom to modern S/M subcultures) where suffering is central to the

production of the subject. Most other academic works on pain follow

this logic, such as Roselyne Rey, The History of Pain, trans. Louise

Elliott Wallace, J. A. Cadden, and S. W. Cadden (Cambridge: Harvard

Univ. Press, 1993); David B. Morris, The Culture of Pain (Berkeley:

California Univ, Press, 1991); and Morris, Pain as Human Experience: An

Anthropological Perspective, ed. Mary-Jo Delvecchio Good, Paul E.

Brodwin, Byron J. Good, and Arthur Kleinman (Berkeley: California Univ.

Press, 1992). Psychoanalytic theory has offered a useful approach to

the question of identity and the eroticization of suffering, most

recently in Leo Bersani, "Is the Rectum a Grave?" October 23 (1987):

197-222; and Kaja Silverman, Male Subjectivity at the Margins (New

York: Routledge, 1992). |

|

| 15

In particular, Stephen Greenblatt has argued that the early Protestant

structure of constancy, the form of interiority so clearly manifest in

Foxe, is not analogous to the individualized and private virtue which

would emerge with the intense autobiographical self-scrutiny of

seventeenth-century Puritans. For Greenblatt, the inner constancy of

the martyr was produced through theatrical spectacle, as the early |

|

| Tudor

nonconformist was a subject produced by a performative repetition of

narrative models or archetypes, a "creature of the book" that demanded

a communal or public representation. See "The Word of God in the Age of

Mechanical Reproduction," in Renaissance Self-Fashioning (Chicago:

Univ. of Chicago Press, 1980), 74-114. See also Francis Barker, The

Tremulous Private Body (New York: Methuen, 1984); and Goldberg, James I

and the Politics of Literature (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Univ.

Press, 1983). The uses to which Foxes text is put throughout the

sixteenth and seventeenth century exhibit the ideological instability

of martyrology. Acres and Monuments at its inception was profoundly

orthodox, with clear high church and monarchical sympathies. But by the

early seventeenth century the text was deemed by the status quo to be

threatening enough to cause Laud to refuse a license for a new edition.

By that point, Foxes work had become vital to radical nonconfomists as

a foundational text supporting the resistance to centralized authority

in favor of individual conscience. So, despite his declaration of

allegiance to centralized ideologies, Foxe produced a text that

resisted enclosure within a hierarchical ordering of church and state. |

|

| 16

As Katherine Eisaman Maus eloquently puts it, new historicist critique

"often seems to assume that once this dependence [on social context] is

pointed out, inwardness simply vaporizes, like the Wicked Witch of the

West under Dorothy's bucket of water" (Inwardness and Theater in the

English Renaissance [Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1995], 28). |

| 17

For a discussion of the truth found in the violation of the body see

Jonathan Sawday, The Body Emblazoned: Dissection and the Human Body in

Renaissance Culture (London: Routledge, 1995). |

| 18

Bishop Ridley's death, like Hooper's, is paralleled with Polycarp's in

a way that emphasizes the reality of his suffering. Rather than

refusing to be bound to the stake as did Polycarp, Ridley calls "good

fellowe knocke it in harde for the fleshe will have his course" (1378).

And then as the badly lit fire slowly burns, Ridley voices a tragic

parody of the miracle that kept Polycarp from burning, crying "lette

the fier come unot me, I cannot burne" (1378). |

|

| 19

Elizabeth Hanson has argued for an early modern ethos of truth in

suffering in her interpretation of the legalization of torture in the

late sixteenth century, when the tortured body became the contested

site of identity as "Elizabethan torturers sought to establish

discursive hegemony by forcibly appropriating their victims' speech.

Their victims, in struggling to maintain religious discourse in the

torture chamber, sought the same end by holding their enemies'

discourse at the frontier marked by torture" ("Torture and Truth in

Renaissance England," Representations 34 [Spring 1991]: 61). Debora

Shuger has also recognized the importance of suffering to constructing

the truth of self-authorized subjectivity; she sees the construction of

characters with "psychic depth" in Shakespeare as part of the

appropriation of religious structures of subjectivity to the realm of

the secular, which "demarcate[s] a generic selfhood distinct from one's

public, social identity-a selfhood already present in medieval

religious texts but in Shakespeare for the first time transposed into

secular, literary forms" ("Subversive Fathers and Suffering Subjects:

Shakespeare and Christianity," in Religion, Literature, and Politics in

PostReformation England 1540-1688, ed. Donna B. Hamilton and Richard

Strier [Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press], 59). |

| 20

For investigations on the importance of Askew, see Elaine B. Beilin,

Redeeming Eve: Women Writers in the English Renaissance (Princeton:

Princeton Univ. Press, |

|

| 1987);

and Megan Matchinske, Writing, Gender, and State in Early Modern

England: Identity Formation and the Female Subject (New York: Cambridge

Univ. Press, 1998). |

| 21 John King,

English Reformation Literature: The Tudor Origins of the Protestant

Tradition (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1982), 25. Torture had

been outlawed in England since the twelfth century, but came back into

use briefly with the pursuit of Jesuits in the later part of

Elizabeth's reign (see Hanson). My concern is not with the specific

function of torture, but the erotic inflections surrounding

representations of torture. |

|

| 22 Anne Askew, The Examinations of

Anne Askew, ed. Elaine V. Beilin (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1996),

127-28. |

| 23 Askew, 128. |

| 24

Bruce Smith states that the equation of loss of control with

heterosexual desire was "a standard topos in Renaissance moral

philosophy." Homosexuality in Shakespeare's England (Chicago: Univ. of

Chicago Press, 1991), 35. |

| 25 Matchinske, 24-52. 2 Matchinske,

29. |

|

| 27 Frances Dolan, "`Gentlemen, I Have

One More Thing To Say': Women on

Scaffolds in England, 1563-1680," Modern Philology 92 (1994): 162. |

| 28

For a discussion of the importance of the story of Lucrece's rape to

Renaissance humanists, not only as it originates in Livy but as it is

rewritten multiple times (Shakespeare's is only the best known English

version), see Stephanie Jed, Chaste Thinking: The Rape of Lucrece and

the Birth of Humanism (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1989). Jed

argues that Lucrece's rape was "a paradigmatic component of all

narratives of liberation" (49), and that the violence exercised on

Lucrece legitimized the establishment of republican government not just

for ancient Rome but for other Renaissance republics. For discussions

of the representations of Lucrece in early modern England, see Nancy

Vickers's The Blazon of Sweet Beauty's Best': Shakespeare's Lucrece,"

in Shakespeare and the Question of Theory, ed. Patricia Parker and

Geoffrey Hartman (New York: Methuen, 1985); Maus, "Taking Tropes

Seriously: Language and Violence in Shakespeare's Rape of Lucrece,"

Shakespeare Quarterly 37 (1986): 66-82; Jonathan Crewe, "Shakespeare's

Figure of Lucrece: Writing Rape," in Trials of Authorship: Anterior

Forms and Poetic Reconstruction from Wyatt to Shakespeare (Berkeley:

Univ. of California Press, 1990), 140-63; Coppelia Kahn, "Lucrece: The

Sexual Politics of Subjectivity," in Rape and Representation, ed. Lynn

A. Higgins and Brenda R. Silver (New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 1991),

141-59; and Mercedes Maroto Camino, "The Stage am I": Raping Lucrece in

Early Modern England (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Wellen, 1995). Katherine

Eggert's elegant and complex argument about the connection between the

representations of physical rape and theological tropes of the

"rapturous" in "Spenser's Ravishment: Rape and Rapture in The Faerie

Queene" (Representations 70 [Spring 2000]: 1-26), parallels the sort of

double logic I see at work in Protestant martyrlogy. |

|

| 29

This is actually a conflation of two verses, Proverbs 31:26 and 31:30,

in reverse order, which emphasizes the connection between speech and

sexuality and the strategic employment of sexuality as the source for

female speech. |

| In the sixteenth

century the contained female body became a powerful icon of continence

and purity, deployed with particular effectiveness by Elizabeth, whose

virginal body became representative of the boundaries of the state

itself. See Peter |

|

| 30 Stallybrass,

"Patriarchal Territories: The Body Enclosed," in Rewriting the

Renaissance: The Discourses of Sexual Difference in Early Modern

Europe, ed. Margaret W. Ferguson, Maureen Quilligan, and Nancy J.

Vickers (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1986), 123-44; Philippa

Berry, Of Chastity and Power: Elizabethan Literature and the Unmarried

Queen (London: Routledge, 1989); and Susan Frye, Elizabeth I: The

Competition for Representation (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1993). |

| 31 Matchinske, 43. |

| 32 Askew, 12. While John Rogers, the

first of the Marian martyrs, is often

named as the protomartyr of English Protestantism, Askew's influence on

the patterns of Protestant martyrdom is undeniable. |

| 33 Knott 16. |

|

| 34 Foxe does not include these

details in the 1563 edition. These quotes are from the 1583 edition

(1533). |

| 35

For an example of the erotic significance of shaving, see act 5, scene

3 of Christopher Marlowe's Edward II, in Doctor Faustus and Other

Plays. The ritualistic shaving of Edward, along with his death's strong

implications of anal eroticism, "can be seen as an attempt to 'write'

onto him the homoeroticism constantly ascribed to him" (Gregory W.

Bredbeck, Sodomy and Interpretation: Marlowe to Milton [Ithaca: Cornell

Univ. Press, 1991], 76). |

| 36 See Bray, Homosexuality in

Renaissance England (London: Gay Men's Press, 1982), 33-57. |

|

| 37 As Smith says, "like relations

between men and women, [pedophilia] is not a meeting of equals" (41). |

| 38"I

Michel de Montaigne, vol. 1 of Essais (1603), ed. Thomas Secombe,

trans. John Florio, (London: Grant Richards, 1908), 232-33, quoted in

Smith, 41. Bruce Smith has noted the legal connection between early

modern conceptions of rape and sodomy, 33-77. |

| 39 The poem is attributed to "G. G." |

| 40

While this image elegantly connects Bonner's "deformed nature" to

Protestant critiques of transubstantiation, the overdetermined image of

the cannibal also traditionally encloses the excesses of sodomitical

desire. |

| 41 While the secondary

definition of "incontinently" as meaning "immediately" is also

applicable in this context, it is reasonable to see the use of this

word as a pun expressing the hypocrisy of Catholic practice which,

according to Protestant propaganda, masked sexual impropriety with

religious zealotry. |

|

| 42

The identity of the victim in the woodcut is not specified. The

woodcut's caption and the wooded setting could signify either Bonner

beating Hinshaw "in an arbour in his garden" (1689), or it could

represent Miles after he had been taken to Bonner's "orchard" or

"arbor," as the 1583 edition names the location (2044). |

| 43 Slinger, 50. |

| 44

See Deborah Burks's analysis of the carnivalesque tropes in Foxes

representation of Bonner in her "Polemical Potency: The Witness of Word

and Woodcut," in John Foxe and His World, ed. Christopher Highley and

King (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2001). |

| 45

Alan Stewart, Close Readers: Humanism and Sodomy in Early Modern

England (Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press, 1997), 42. See also Donald

Manger, "John Bale and Early Tudor Sodomy Discourse," in Queering the

Renaissance, 141-61. |

| 46 John Bale, quoted in Burks, 15. 47

Askew, 57. |

| 47 Smith, 43-45. |

|

| 49 See Bray, Homosexuality in