| |

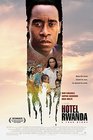

CONSEQUENCES OF WORLD INACTION EXPOSED IN HOTEL RWANDA CONSEQUENCES OF WORLD INACTION EXPOSED IN HOTEL RWANDA

In 1994, Paul Rusesabagina saved the lives of 1,200 persons in his role as manager of Sabena Airline's four-star Hotel Milles Collines in Kigali, the capital of Rwanda. Hotel Rwanda, directed by Terry George, tells that story. As the movie explains through the dialog of various actors, Belgium was once the colonial power in Rwanda. To handle some of the colonial administration, the Belgians favored the lightskinned, urban Tutsis over the more populous darkskinned rural Hutus. In 1962, Rwanda became independent. In 1993, a civil war arose, with Tutsi rebels attacking Hutu-dominated government forces. After a UN-brokered peace agreement in August, the UN dispatched the UN Assistance Mission in Rwanda (UNAMIR) as peace observers, assigned to monitor implementation of the peace agreement but not to use force. But when the airplane of President Habyarimana, a Hutu, was shot down in April 1994, the Hutus suspected Tutsi treachery and mobilized for revenge against the Tutsis, whom they called "cockroaches." In the film, UNAMIR's Force Commander is Colonel Oliver (played by Nick Nolte), though in actuality Brigadier-General Roméo Dallaire held that position in Rwanda. When the film begins, Paul Rusesabagina (played by Don Cheadle) is arriving back in town from an overseas trip. He is surprised to see members of the majority Hutu ethnic group mobilizing for something violent aimed at the minority Tutsis. As Hutu commanders inevitably come knocking at the door of the hotel to demand the heads of all Tutsis, including Rusesabagina's spouse Tatiana (played by Sophie Okonedo), a Tutsi, he calls upon friends in high places to intervene, from his Hutu contacts in the Rwanda army to the president of Sabena Airlines to UNAMIR's Col. Oliver, a Canadian. The foreign press also puts videos of some of the massacres on television screens throughout the world, but the images are just as quickly forgotten; as Col. Oliver notes, the Tutsis are not even "niggers," just "Africans" who can be easily ignored elsewhere. Because the turmoil in Rwanda comes on the heels of the massacre of UN and American forces in Somalia, the UN, Belgium, Britain, and the United States are gun shy. In 1994, Paul Rusesabagina saved the lives of 1,200 persons in his role as manager of Sabena Airline's four-star Hotel Milles Collines in Kigali, the capital of Rwanda. Hotel Rwanda, directed by Terry George, tells that story. As the movie explains through the dialog of various actors, Belgium was once the colonial power in Rwanda. To handle some of the colonial administration, the Belgians favored the lightskinned, urban Tutsis over the more populous darkskinned rural Hutus. In 1962, Rwanda became independent. In 1993, a civil war arose, with Tutsi rebels attacking Hutu-dominated government forces. After a UN-brokered peace agreement in August, the UN dispatched the UN Assistance Mission in Rwanda (UNAMIR) as peace observers, assigned to monitor implementation of the peace agreement but not to use force. But when the airplane of President Habyarimana, a Hutu, was shot down in April 1994, the Hutus suspected Tutsi treachery and mobilized for revenge against the Tutsis, whom they called "cockroaches." In the film, UNAMIR's Force Commander is Colonel Oliver (played by Nick Nolte), though in actuality Brigadier-General Roméo Dallaire held that position in Rwanda. When the film begins, Paul Rusesabagina (played by Don Cheadle) is arriving back in town from an overseas trip. He is surprised to see members of the majority Hutu ethnic group mobilizing for something violent aimed at the minority Tutsis. As Hutu commanders inevitably come knocking at the door of the hotel to demand the heads of all Tutsis, including Rusesabagina's spouse Tatiana (played by Sophie Okonedo), a Tutsi, he calls upon friends in high places to intervene, from his Hutu contacts in the Rwanda army to the president of Sabena Airlines to UNAMIR's Col. Oliver, a Canadian. The foreign press also puts videos of some of the massacres on television screens throughout the world, but the images are just as quickly forgotten; as Col. Oliver notes, the Tutsis are not even "niggers," just "Africans" who can be easily ignored elsewhere. Because the turmoil in Rwanda comes on the heels of the massacre of UN and American forces in Somalia, the UN, Belgium, Britain, and the United States are gun shy.

|

The Belgian contingent leaves UNAMIR, precipitating a withdrawal of forces from other countries. France is supplying arms to the Hutus, thus taking sides. Rather than increasing the strength of UNAMIR and directing the force to stop what Washington euphemistically calls "acts of genocide," the UN mission is scaled down from 5,000 to 270 soldiers, and all Caucasian foreigners are given safe conduct out of the country. Rwandan refugees then pour in to the Hotel Milles Collines, the premier hotel of the country, and Rusesabagina assumes responsibility for feeding and housing them until Col. Oliver, who remains in charge despite the pullout, arranges a convoy to refugee camps near the Tanzanian border, from which they are bussed to safety in Tanzania as armed Tutsi rebels advance on Kigali. Rusesabagina's courage and resourcefulness, taglined "When the world closed its eyes, he opened his arms," contrasts with the horrors of the three months in which approximately one million Rwandans were slaughtered, mostly by machetes. Titles at the end indicate that Rusesabagina, a consultant in the making of the film, now lives in Belgium with his wife and family, and that two of the organizers of the genocide are now imprisoned as a result of war crimes trials. The Political Film Society has nominated Hotel Rwanda for awards as best film exposé of 2004, best film in raising consciousness about the need to respond to human rights crises, and best film raising consciousness about how peaceful solutions to conflicts are preferable either to violent methods or to the abandonment of the Rwandans by the international community to the genocide that occurred. Hotel Rwanda makes a powerful statement at a time when history is repeating itself as the residents of Darfur, Sudan, face a similar catastrophe and the international community's dilatory response is insufficient to prevent hundreds of thousands of refugees from spilling across the border into makeshift camps. MH

YVONNE KOZLOVSKY GOLAN CONTRIBUTES THIRTY-FIRST WORKING PAPER

The Birth of the Holocaust in Motion Pictures, which was presented at the Film & History conference in Ft. Worth during mid-November, is the latest contribution to the Working Paper Series of the Political Film Society. The author, an Israeli scholar, discovers that early black-and-white images of the Holocaust were carefully organized and yet are still seen as authentic even though color footage was taken at the time. The essay is available for a donation of $5, as are all the other Working Papers, which are listed on the Society's website.

|

|