Shrill cries shattered the morning quiet and a group of naked boys rushed wildly toward the river, their bare feet heedless of the rough ground of the pampa. A few undernourished dogs yelped about their legs. A bald-headed vulture, annoyed by the intrusion, raised its beak from a decaying carcass, then lifted itself heavily into theair. For a few moments it hovered high up hawking raucously, then flapped away into the early sun. A long-legged Patagonian hare - waked from sleep - darted blindly in front of the boys, stopped, bounded off and was lost in the brown scrub lining the riverbank. Barking excitedly, the dogs scampered on its trail. "After him!" cried the boys.

Love of the hunt was second nature to them. They were too young to hunt big game like the guanaco, the rhea and the puma. But chasing small game like the diminutive pampa deer or the hare was a favorite pastime.

But now even this was not to be.

"Stop!"

At the command the boys halted and looked up at their leader.

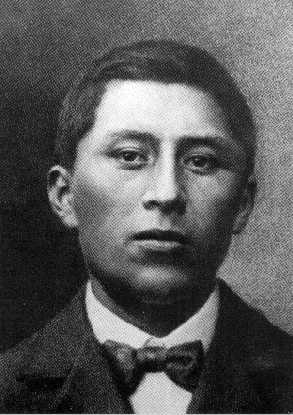

At twelve years of age he was stockily built and muscular with a short neck; his feet were scarred at the edges and the toes long and separated. His thick black hear fell around his ears but was cut straight across the brow and bounded with a bright cloth band. The face was squarish, the mouth large and tending to heaviness, giving the impression of a stoic and unresponsive disposition - had it not been for the eyes. These were lively, intelligent and at the same time warm and outgoing. The other distinguishing feature was his complexion. This was of a lighter shade and of more delicate texture than that of his companions.

"To the river!" he cried. With that he dashed ahead and the others quickly followed. At the sight of the chilling, iron-brown depths of the river, however, their enthusiasm vanished. The leader also halted, but only for an instant. Then he plunged in. The next moment the others, squealing with delight, churned the water into a foaming caldron of squirming arms and legs.

With short, powerful strokes the leader reached the opposite bank and climbed on a rock. "Follow me!" he called. Waiting just long enough for them to scramble out of the water, he raced off in the direction of the tolderia. In and out between the toldos he led his companions, leaping over this obstacle, running under that; now he sped into the nearby scrub, now over rocks, now doubling up through lean-tos, until thoroughly exhausted, he threw his glistening wet body on the ground, breathless and laughing. His companions followed and lay beside him panting. Once they had regained their breath they began to chatter excitedly.

Suddenly, at the sound of a woman's high-pitched voice, their chatter ceased. The voice called a second time, louder and more insistent. Finally, on of the boys shrugged his shoulders, rose to his feet and hurried off. Another voice called, and another boy rose. Evidently the women had completed their morning ritual at the upper part of the river.

Though some twelve years had elapsed, the leader could still hear the soft padding of his mother's naked feet as in the semidarkness she carried him to the river. She would first bathe herself quietly, then lower him into the undulating water, rubbing him vigorously to keep him from becoming numb. After drying him in the rough cloth which covered her while she washed, she would envelop him in a warm lambskin and lay him on the riverbank. This left her free to wash the cloths she had brought, soaping them with crushed chacay leaves and beating out the sudsy dirt with a paddle. Gathering him up together with the clothes, she would hurry back to to the tolderia which had become discernible in the early light.

Now he heard her calling him and like the others he made his way along the dustry tracks to a large toldo stadning by itself in the center of the tolderia.

In the early days the toldo was a tent of skins erected hastily or with care depending on the length of stay. Now it was built with thatched roof and adobe walls. The light came through the door which faced away from the constant cold wind from the4 southwest. The dark interior was painted with red earth fixed with rhea grease. The family possessions, including pigs and chickens, were stored inside.

Without a word the boy squaated with the rest of his family around the shallow fire pit in the center. His mother handed him a gourd of stew made from maize andchunks of guanaco meat. She wore a black garment of homespun held to her body by a cloth belt, and over this a shawl fastened at her bosom by a heavy silver brooch. She had bound her hair with a headband of silver coins.

"Zepherin," she said, "although it is not yet summer you were early in the river this morning. Was it not too cold?"

The boy was about to reply when a deep voice rumbled from the shadows of the toldo.

"Woman, it is never too cold for a Cura. Just as it is never too hard for a Cura to lead his men into battle."

"Husband," protested Rosaria, "we are no longer at war. We no longer raid or kill."

"In peace or war a Cura must always honor his name. And Zepherin has a friend in the spirit of the river."

Zepherin remembered how long ago, when he was an infant, he had tumbled into the Rio Negro and the turbulent waters had rapidly borne him beyond help. Miraculously, he had floated downstream until the river had deposited him on its banks. His father had told him that the spirit Gneche had plucked him out of the water. But the black-robed huinca had poured water over him in some sort of incantation. He had told the cacique he did not like to hear anyone say that. It was God, he said, who had saved the child and it was clear God must have important work in store for him.

After eating, Zepherin withdrew and threw himself on a thick brown-and-white guanaco skin in the corner of the toldo. He pulled a second one over him, laid his head on a smooth block of woodand, undisturbed by the noise the others made, fell asleep.

In earlier times when not at war or hunting, the usual occupation of the male was lolling on the floor of the toldo swapping stories or just sleeping. Sometimes it included spying on the enemy, on the cacique, or even on one's own father or son. The rest of the time they spent in horse-racing, gambling, or taking care of their hunting gear. As son of the cacique, Zepherin was accustomed to being left alone. Too much discipline might destroy his initiative. Zepherin still remembered the story of Waiquiner, son of the cacique Mariano.

Waiquiner's father, after drinking, had begun to beat his wives, making them huddle fearfully in a corner. When he had finished beating his first wife he staggered across the toldo to seize his second. This was Waiquiner's mother. Mariano found his way barred by a sturdy young Indian with a dagger in his hand.

"Stop!" ordered Waiquiner.

"Stop? Why?"

"I forbid you to touch my mother."

"You forbid me? And if I do?"

"I will plunge this dagger into your heart," Waiquiner replied evenly.

"Suppose, instead, I kill you?"

"I do not care. But I will not let you touch my mother."

Waiquiner's father stared at him for a while. Then he stumbled off drunkenly to his pallet.

"Come here, son," he called out eventually. Waiquiner approached him cautiously. "Put that knife away, you need not be afraid," the chief urged. "You have a brave heart. You are a true son of mine." Taking the boy on his knee he turned to the cowering women. "Worry no more tonight. Waiquiner's courage has saved you from a beating."

The boys had loudly applauded Waiquiner for his manliness. Zepherin, on his part, had also assured himself that he would have done the same if anyone had dared to lay a finger on his mother. But when he thought of the kind of man his fatheer was he wondered who, whether boy or man, could stop him from doing what he wanted.

When the sun had risen over the mountains Zepherin opened his eyes. Bending over him was a young girl. She peered down at him for a moment until she was sure that he was fully awake. Then she wagged her finger reprovingly.

"Lazy brother!" she scolded. "Sleep like that during the day and the Colocolo lizard will creep up on you and drink your blood. Or else the Chonchon bird will make your head fall off! I heard him cackling in the woods yesterday. Someone is going to die! So get up, lazy brother, or it might be you!"

"Puah!" Zepherin turned his head away. "Clarisa, you talk like a little child!" He ran the tip of his tongue across his upper lip. It would be a long time, apparently, before he would be obliged to pluck hair off his face. His gaze fell on the length of tendon hanging over his bed. The knots told him that it was the forth day of the week. Suddenly he remembered what lay ahead. Quickly throwing off the rung, he stood up and stretched under the admiring gaze of Clarisa.

"Mama," he said, "do I have to fetch wood and water? Cousin Bernard promised to teach us how to throw the boleadora, and do trick riding and shooting. Besides," he drew himself up, "the son of the cacique ought not be seen so often fetching wood and water. They will say I am a woman."

"Zepherin," replied his mother, "rarely will any of the others help me the way you do. But yesterday you cut enough wood for today as well."

"I can fetch the water," offered Clarisa.

"Go with your friends, my son." His mother smiled as she watched him bound out of the toldo, making no attempt to hide his pleasure.

It did not seem so long since she had carried him on her back or leaned his cradle-on-a-stick against a tree while she went about her chores. When he began to walk, she tethered him on a stake to make sure he did not wander. What contentment to cuddle him in bed each night and bathe his eyes with the milk of her breast against disease, to massage his nose carefully to flatten it out handsomely! She had not pierced his ears, since earrings, once the symbol of authority, were going out of style. How proud she was that Zepherin had not been a twin or had been deformed! For then she would have had to destroy him. She had not even bloodlet him to drain off the evil influences, so that he would grow up to be a great cacique like his father. Zepherin told her that he loved her very much but did not like to be reminded of the days when he was a helpless baby.

Once out of the toldo Zepherin was quickly surrounded by a group of boys.

"What shall we do today, Zepherin?"

"Today we shall practice horse-riding, throwing the boleadora and shooting the bow and arrow. Cousin Bernard stayed behind from the hunt to teach us . . . Look! There he is, waiting for us at the top of the hill. Let's race! Gualichu catch the last one!" The boys dashed after him, shouting war cries their fathers had once used in their fierce malones.

At the top of the hill stood a man wearing an open-neck shirt, wide trousers, and half-length coltskin boots. His bobbed hair was bound by a bright red-and-white cloth band and around his neck he had tied a yellow-and-blue kerchief. The moment he saw the boys appraoche his seized his boleadora by the strap uniting the three cords, and swung the three iron balls around his head. When they had gathered sufficient momentum, he leaned forward and flung them at the foremost boy. Sailing through the air like a giant three-legged spider the boleadora caught him at knee level, swirled about his legs and bound them tightly together. In a vain attempt to balance himself the boy threw up his arms, then pitched headlong to the ground and rolled over. For a moment he lay still, then he sat up while Zepherin and the others helped him unwind the boleadora. Holding it dangling from his hand, Zepherin ran to the top of the hill. "Cousin Bernard," he cried, "you must teach me how to throw like that!"

Bernard first showed them how to grip the thong of the single bola and how to release it at the precise moment. Placing the boys a good distance from one another he told them to practice throwing. By way of a flourish he also demonstrated his expertness with both the double and the triple boleadoras. He could even separate one of the whirling bolas while still keeping the other two in motion.

He was giving a lesson to Zepherin when one of the boys let out a scream and fell. Zepherin raced up behind his cousin and when they reached the boy, they found him unconscious. Disobeying Bernard's orders, the boy had started to swing the boleadora. The boleadora balls had flown out of control, and one, circling wildly, had struck him in the temple. A series of shakes, punches on the body, and slaps in the face finally revived him. When he realized what had happened, h e stoically took his place with the others without as much as a nod of thanks.

"That will do for the boleadora," said Bernard. "Let's try the riding tricks our fathers used in outwitting the huinca." He led them to a level stretch of ground where he had tied three horses to a tree. They had no apparel other than a sheepskin saddle and a bridle of twisted leather thongs.

It was still more than Zepherin had used on his first ride. That was when his father had taken him -- barely eight years old -- to the corral. The cacique had lifted him on to the broad, glistening back of a large roan, had placed his two tiny fists on the horse's mane, and without warning had given the horse a smack on the rump. The horse did not even turn its head; it bolted! The child's hands instinctively stiffened on the mane, as he clung on desperately with arms, legs and feet to avoid being jolted off that broad, bounding back.

Fortunately, the horse, sensing that its little burden presented no danger, soon came to a breathless halt. Then it quietly cantered back to its master. Laughing heartily, his father had taken him in his arms and placed on tiny hand on the horse's muzzle. The warm velvet touch soothed the boy and he kept stroking the horse's head until his father carried him back to the toldo. After that, riding became second nature to him. He was constantly running to the horses, and had been kicked more than once as he dashed in and out between their legs.

The boys now were intent on learning the tricks for which the Indians were famous. Many of these were purely acrobatic but some were relics of the days when they had fought the white man in defense of their homeland.

To demonstrate one of the more difficult tricks, Bernard led out a piebald with a bushy tail. Leaping into the saddle, he cantered off briskly for about a hundred yards, wheeled, and with a jerk of his thighs sent the horse racing toward them. As the horse dashed forward, Bernard let his body slide over so that when it came alongside, the boys could see nothing of its rider, until he let himself slide still further and appeared with his head hanging below the horse's belly. Then he quickly swung back into the saddle. The boys cheered.

As he walked over to the horse which carried the bundles of bows and arrows he found Zepherin blocking his path. Bernard wanted to brush past him but an appealing look in the boy's eyes stopped him.

"Well?" he asked gruffly. He already suspected what the request would be and was preparing to deny it.

"Could you let me try . . . just once?"

"Too dangerous yet."

"Cousin," pleaded the boy, "if I do not make the attempt just because it is dangerous, will the others consider me their leader and a true son of the cacique?"

Bernard studied the boy's face. It was always difficult to refuse a request from Zepherin.

"All right," he said. "But take no needless risk."

He had hardly finished speaking before Zepherin dashed to the piebald, leaped lightly into the saddle and was soon racing away. In imitation of Bernard he wheeled sharply and sent the horse dashing toward the group. As he approached he gradually slid across the broad girth of the animal, then down the side until he had disappeared. The boys held their breath, waiting for him to appear beneath as Bernard had done so that they could shout their applause. Instead, they heard a wild yell as something hit the ground with a thump, a cloud of pampa dust shot up, and a riderless horse raced past them. Zepherin lay where he had fallen, having thrown himself clear of the horse's flying hooves. When Bernard and the others reached him, he quickly rose to his feet. Covered with dust, his eyes red as fire, he still managed a wry smile.

Bernard stared at him. "Hurt?"

Zepherin shook his head vigorously.

His cousin continued to look at him. Finally, he walked over to the second horse, untied several long bundles of bows and arrows. Throwing the bundles at his feet he chose from them a heavy bow that reached up to his shoulder, plucking at the arc once or twice to test its strength. Carefully inserting the string in the nock of an arrow, he drew it back until his fingers were level with the corner of his mouth. Slowly and dramatically, for he was not insensitive to the admiration of the boys, he leaned backward, pointing the arrow straight up and let the string snap free. Then he kept his eyes fixed on the arrow as it soared heavenward. When it reached its zenith, it hovered for an instant, poised, turned upside down and began its swift fall to earth. Without the least expression on his face, Bernard took one casual step backward and watched the arrow plunge into the earth and stick, upright and quivering, exactly in the spot where he had been standing! With the slightest of nods he acknowledged the boys' applause.

When, without success, the youngsters had made several attempts to equal his feat, he glanced at the sun and told them to collect the bows and arrows. While they were watching Bernard bind them together, Zepherin suddenly seized the straight black hair of a companion and pulled with all his might. Quickly recovering, the boy shot out his hands, seized Zepherin's hair and the two began a test of endurance in which each one tried to cause the other so much pain he would cry out for mercy. Immediately forming a circle around the contestants, the boys took sides, inciting them to even more vigorous tugs.

How the contest would have ended is difficult to say. Although Zepherin could see tears in the eyes of his opponent, he was beginning to find the pain unbearable. Fortunately, Bernard was ready to go and did not want to be delayed by childish games. Besides, the length of the shadows warned him that the day was well advanced.

"All right," he called out. "Time to leave. No winner and no loser."

Fatigue and hunger had now overtaken the group and they pulled the contestants apart. When Bernard sang out, "On horse!" they gleefully swarmed up on the backs of the horses.

It was only when Zepherin had seated himself firmly on the horse that Bernard noticed the large red welt on Zepherin's side. He touched it gingerly; the flesh twitched. Zepherin looked into Bernard's eyes and flashed a smile. Bernard smiled back in understanding.