Doctor of discretion

'Niles babies' sift secrets

of home for unwed mothers

|

|

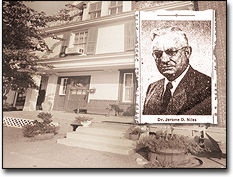

At 11 E. Main St.

in Middletown, Dr. Jerome D. Niles operated a home for unwed mothers in

the 1930s and early 1940s.

|

Dover Bureau reporter

10/08/2000

MIDDLETOWN -- An old brick

residential building in downtown Middletown has become the focal point

for an untold number of middle-aged men and women searching for their true

identity.

Behind the doors at 11 E.

Main St., Dr. Jerome D. Niles operated a home for unwed mothers in the

1930s and early 1940s -- and the confidentiality he promised has nearly

closed the door to the information the babies born under his care are so

desperately seeking.

Those babies, now in their

50s and 60s, are asking simple questions that most people can answer without

a moment's thought:

Who was my mother?

Who was my father?

Where am I from?

These are questions that

people such as Ann Weinblad and Terry Sheron can ask but not answer.

Their mothers became pregnant

at a time when abortion was virtually unavailable and unwed motherhood

was perhaps the greatest shame a woman could bring upon her family.

These young women needed

a secluded place to spend the last months of their pregnancies, competent

medical care and an assurance that a good home would be found for their

babies.

So they came to Niles, whose

home for unwed mothers promised the utmost in discretion.

Now, a half-century later,

that discretion is causing heartache and frustration for the babies who

passed through his doors.

Few records exist and those

that do are suspect. The doctor and his secretary are dead, their files

apparently destroyed. No one even knows for sure how many babies Niles

delivered.

Nothing about the babies

Jerome D. Niles was born Feb.

28, 1884, in Kinneyville, Pa. He graduated from Lock Haven State Normal

School in Lock Haven, Pa., and received his medical degree in 1905 from

Medico-Chirurgical College in Philadelphia.

When he took the Delaware

medical licensing exam in 1910 he scored a 75.8 -- with 75 being the minimum

passing score.After

completing his residency in Philadelphia, Niles moved about 1907 to Townsend,

where he would live the rest of his life.

A respected physician, Niles

served as president of the Delaware Medical Society and the New Castle

County Medical Society. In 1945, he was named president of the state Board

of Health. A street in Townsend bears his name.

Sometime about 1930 -- the

records have been lost or destroyed -- Niles converted his general practice

in Middletown into a home for unwed mothers.

"They had a regular hotel-like

setup for them, rooms, areas for cooking," said John Weid- lein, who owns

the building. "It was nice. It was a high-class place."

Some of the Niles babies

have found their way to Weid- lein's doorstep in recent years, but he has

little information to give them.

Niles "had a nurse who knew

the names of the girls and their parents, and when he passed away she refused

to give away any of the information," Weid-lein said.

Thinking back on conversations

he had years ago with old-timers who remembered Niles, Weidlein was struck

by what they omitted.

"Everyone knew that he had

a home for unwed mothers, but no one ever said anything about the babies,"

he said.

"I don't remember anyone

saying anything about the babies."

From time to time, a Niles

baby arrives in Middletown, hoping to put together the pieces of a puzzle

that have been scattered by the winds of time.

Niles died Jan. 18, 1963.

Chances are, the person will

end up at Butler & Cooke Antiques at 13 E. Main St., an old brick building

that housed the Peoples National Bank before it went bust during the Depression.

There they will find proprietor

Jan Butler ensconced among her lamps and other artifacts.

"These people say, 'I want

to see this place. This is where I was born,' " Butler said.

Or they might end up next

door at 11 E. Main St., looking for a clue about the residential building's

past.

Sometimes they will find

their way to the office of Ellen Combs-Davis, a septuagenarian who has

lived her life in Middletown and seen her share of local history.

There they might show her

a birth certificate, their only real link to a mother they never knew.

Combs-Davis will share what

she knows about Niles, but there is little she can do to help.

A finder of families

Ginger Farrow bills herself

as "Delaware's only finder."

She helps adoptees who are

seeking their birth parents, and birth parents who are seeking their natural

children.

She does not speak highly

of Niles.

Because Niles was paid by

the unwed mothers and may have collected fees from couples who adopted

the babies, his actions were unethical, Farrow said.

And because many of the Niles

babies wound up with birth certificates bearing inaccurate or misleading

information, and normal adoption procedures were skirted, Farrow places

Niles squarely in the ranks of the black-market baby operations so prevalent

in the 1930s and 1940s.

"Adoption is a moneymaking

business," Farrow said. "Nobody wanted to deal with it back then, and people

don't want to deal with it today."

According to Farrow, who

has tried to help several Niles babies research their origins, many of

the unwed mothers were young Jewish women from New York and northern New

Jersey. Many of the babies were placed with Jewish families in those areas.

The lack of verifiable information

in the Niles adoptions has made it almost impossible for Farrow to help

the Niles babies who have come to her for help.

"So many of them have false

names," Farrow said.

One of the Niles babies who

came to Farrow for help was Ann Weinblad.

A quest for Betsy Ross

Weinblad was born on Flag Day

1938. Her birth certificate says her name is Betsy Ross.

Curiosity about her birth

certificate led Weinblad on a quest in search of her identity, a quest

that led from her home on Long Island in Williston Park, N.Y., to Middletown.

Weinblad is 62, a Long Island

resident who said her chief occupation has been "raising children, dogs

and turtles."

When she was a child, her

parents told her she had been left on the steps of an orphanage, and because

it was June 14 -- Flag Day -- the orphanage named her Betsy Ross.

Her parents gave her their

last name -- Arnold -- but when she was 21, she asked for her adoption

papers. Her birth certificate identified Weinblad as Elizabeth Ross.

She eventually learned that

her birth mother's name probably was Ross, but that the woman's first name

most likely was a fabrication.

Weinblad also learned that

her adoptive parents picked her up in Langhorne, Pa., home of The Veil

-- a notorious babies-for-sale operation ruun by Charles M. Janes and his

wife.

The Veil, which also operated

a maternity home at Marshall and Matlack streets in West Chester, Pa.,

was denied a license by the state and was forced to close in the late 1930s.

Weinblad's sister wasn't

a Niles baby. She was a Veil baby, adopted through the West Chester home.

Other Niles babies searching

for their roots have gravitated toward Weinblad, and they share their experiences

with her.

Some people told her Niles

placed advertisements in the Jewish newspapers in Brooklyn about his services,

Weinblad said.

Weinblad went to Middletown

several years ago and met with Niles' secretary, Rebecca Bramble.

"I was trying to endear Rebecca

Bramble to me. I wrote her a letter, how [Niles] really helped out a lot

of people and he helped a lot of babies," Weinblad said.

But Bramble could not or

would not supply any information.

Weinblad is frustrated with

the New York state law that keeps her from seeing the papers her birth

mother may have signed giving her up for adoption.

She said she harbors no ill

will toward Niles. But she said she does find the legacy of Niles' practice

somewhat distasteful.

"Of course, he was in it

for the money," Weinblad said.

"It was a good market. It

was a good business, and it is a good business today. People who are attempting

so desperately [to have a baby] will pay any price," she said.

"It's kind of sordid, no

matter which way you look at it."

A family of Niles babies

Terry Sheron of Litchfield,

Conn., comes from a family of Niles babies.

Her older brother was born

in West Chester, Pa., in 1937 -- possibly at The Veil.

Niles delivered her younger

brother in 1944 in Middletown.

And though she has no birth

certificate to prove it, Sheron has concluded she was delivered by Niles

in 1938.

"How my parents found him,

I'd like to know," said Sheron, who sells display advertising at a small

Connecticut newspaper.

Sheron stumbled across the

fact that she was adopted during a conversation with an aunt in 1985.

"In 1985, I went to my mother

and told her, 'It's time, here it is,' " Sheron said. "She was very upset."

Sheron's mother "couldn't

and wouldn't remember anything," she said.

Sheron believes her parents

went to Niles for their children because they might not have qualified

for a conventional adoption.

"My parents were older, and

probably going for a newborn infant. My mother was 38, my father about

the same age. I would think that had been a factor," Sheron said.

Sheron's older brother, a

major in the Air Force, died in 1972, never knowing he had been adopted.

Her younger brother's birth

certificate, signed by Niles, lists the adoptive parents as the birth parents

-- a ruse used at The Veil and other black--market baby operations to circumvent

adoption laws.

"These guys were taking money

from the customer and taking money from the pregnant mother. They were

taking money both ways," Sheron said.

Sheron has three sons and

four grandchildren, and wishes she could tell them something about their

heritage.

But with no birth certificate

and little hope of ever finding one, she cannot.

Though Sheron remains angry

about the circumstances of her adoption, she wants to believe that perhaps

the Middletown physician "really had a good heart."

Regardless of Niles' motivation,

the hurt remains.

"I just feel outraged, because

my mother, when I told her I needed to know who I was, she was of the old

school and her remark to me was: 'You know, I just could have left you

there. I could have left you there.' And it cut so deep ... "

Doing society a favor

Ellen Combs-Davis has lived

her life in the town where she was born, and she remembers Niles and his

family.

"His younger son John was

killed in an airplane accident a day before he went in the service for

World War II," Combs-Davis recalled.

The Nileses' other son, Jerome

D. Niles Jr., died in 1998. Some of the Niles babies who tracked him down

said they found him either unwilling or unable to provide any information.

The doctor's wife, Loretta

Niles, died in 1980.

Niles' only living relative,

a granddaughter who lives in the Washington, D.C., area, said she had no

information on the doctor.

Not long ago, a woman approached

Combs-Davis, looking for information.

"She was born at the Delaware

Hospital; she said she understood her mother had worked in a bank on Main

Street in Middletown and that she lived on East Main Street," Combs-Davis

said. Delaware Hospital is now Wilmington Hospital.

Combs-Davis told her where

Niles' office was, and that the bank -- now the antiques shop -- was next

door.

The woman showed Combs-Davis

a birth certificate, but the birth mother's name had proved to be bogus.

"I said, 'Well, it would

be natural for your mother not to use her real name,' " Combs-Davis said.

"She was glad to get that far, but I couldn't tell her anything else."

Middletown was an ideal location

for a practice such as Niles'. Located on a major north-south highway and

accessible by rail, Middletown was far enough from New York to ensure anonymity

but close enough for convenient travel.

"In those days, when a girl

got pregnant, she would want to go far away from home," Combs-Davis said.

When Niles died, the weekly

Middletown Transcript published a detailed obituary. But no mention was

made of the maternity home at 11 E. Main St., even though "everyone in

Middletown knew about it," building-owner Weidlein said.

Combs-Davis said Niles was

respected in Middletown, and it would be unfair to second-guess his motivation

so many years later.

"He gave a home to unwed

mothers, and protected them and saved their children," Combs-Davis said.

"So he did society a favor."

|