Recently, (January 2008), I received an email from Joe Jadwick from North Carolina. Joe's dad, Raymond, served on the Net Tender USS Nutmeg AN-33, during World War two. Joe had stumbled across this website and was interested in knowing if we ever have any reunions. Of course, I got him in touch with those who are in charge of the ALL NET TENDER REUNIONS. The are already signed up for the October 2009 Reunion. It was a thrill to find another old net tender sailor.

But … (and this is fantastic) … yesterday, (February 4, 2008), I received the following email from Joe with photo:

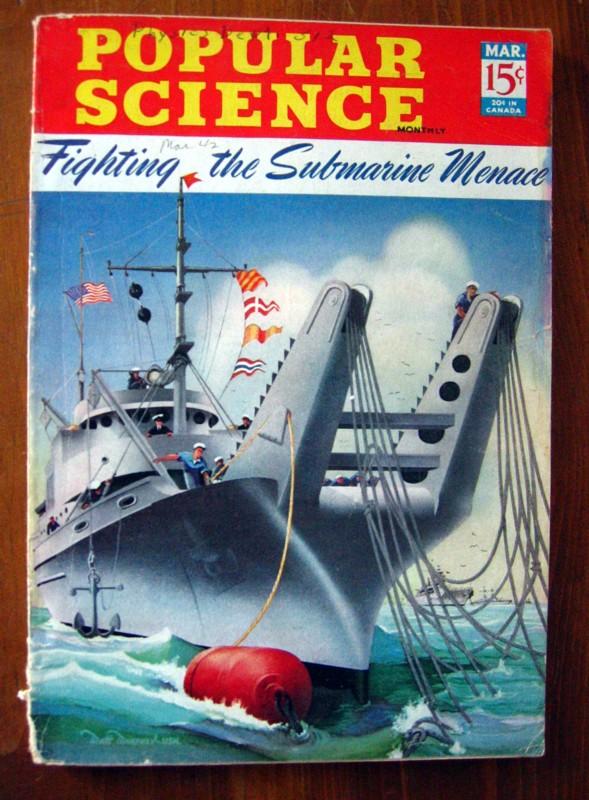

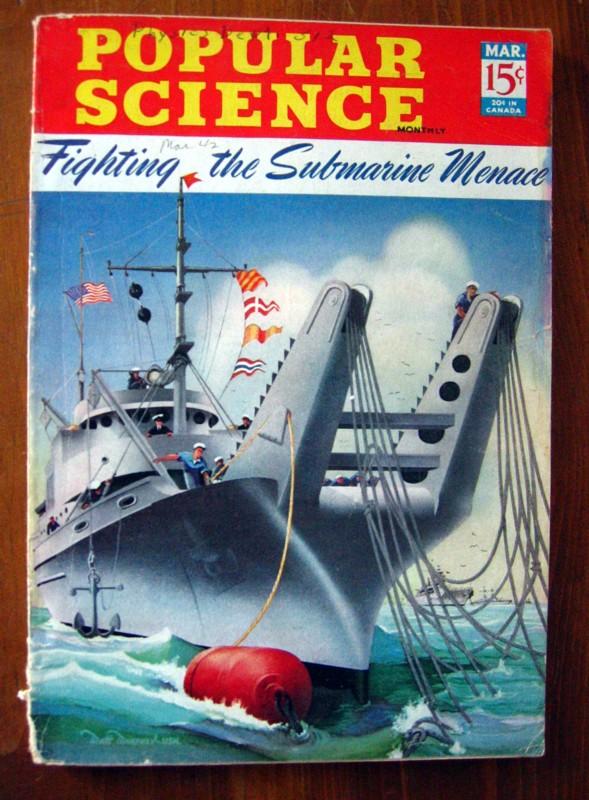

Just bought this magazine on ebay a minute ago.

Wanted to share the info so that everyone knows it is out there

and staying in the family.

Joe Jadwick

Yes ... it is a Popular Science Magazine dated March 1942. Price was 15 cents. You can contact Joe at ... joeaandp@nc.rr.net ...

UPDATE ... 3 March 2009:

His dad Raymond at ... raynrose@verison.net

Today I received the Popular Science Magazine from Joe. It was more than I had ever expected.

Following is the write-up found on pages 49, 50, & 51, of the magazine:

Harbor nets, often supplemented by natural obstacles and by block-ships purposely sunk at suitable points, completely close the mouth of a port. Their floats support a mesh of heavy metal, extending all the way to the bottom and anchored or weighted sufficiently to prevent the entrance of an enemy submarine. Reportedly of as much as three-inch thickness, their close-mesh stops both submarines and torpedoes. So that friendly vessels can enter and leave port thus screened, a movable ‘gate’ section of the net may be opened or closed at will.

The U. S. Navy has already developed special vessels designed from the keel up for the express purpose of handling harbor nets. If they have been turned out on schedule - - war restrictions on launching announcements preclude more definite information - - a fleet of from 70 to 90 or more net boats should now be in service. They fall into three classes.

Most interesting of the new craft are the largest type --- 500 ton vessels intended for laying and repairing nets. From their over-hanging bow gear to their rounded sterns, they have an overall length of about 160 feet. The class includes ships named after trees, such as the U. S. S. Locust, Boxwood, and Gum Tree. So as not to interfere with construction of seagoing men-of-war, many have been built at inland shipyards.

A second type of net vessel, resembling a barge but specifically equipped for its service, acts as the gate of the net. A Pennsylvania shipbuilding and engineering firm has been filling Government orders for many of the 110-foot, motorless craft.

Net-tending tugs, the third class of boats, open and close the gates. They also, on occasion assist in net-laying operations. Many of these 70 to 100 foot wooden craft, it is reported, have been built for the Navy. Others have been purchased from tugboat operators and converted for Navy purposes, as has at least one purse seiner.

During the last world war, tugboats alone served as hastily improvised net-laying vessels, in contrast with the specialized ships now available. Likewise, gasoline drums and beer kegs have given away to large wooden floats, to support the nets.

No less advance has occurred in the art of laying the Army’s controlled harbor mines. In contrast with ‘contact’ mines, the Army mines distinguished between friend and foe. Moored in submerged rows, they are set off electrically by observers in hidden casemates ashore, just as an enemy vessel goes by. Telescope spot the location of surface craft. But if a hostile submarine blunders into one of the mines, the bell immediately rings in the casemate.

U. S. Harbor protection by nets and mines is as vital as it deems strong. New kinds of nets have been developed, and new methods of net laying perfected, including ways to keep the unwieldy apparatus in position. And modern mine planting crews can quickly transform a defenseless port into one that offers a deadly menace to hostile visitors.