Ute use of the Garden area as a winter campground can be attributed not only to the customary absence of rival Plains Indians, but also to the presence of large herds of elk on the nearby mesa. In the early spring of 1858 Captain Marcy of the U.S. Army observed two herds of several hundred elk each there; three years later Melancthon Beach estimated a winter herd of over 300 elk.

An 1860 pioneer named Irving Howbert later recounted the story of 300 Utes under Chiefs Ouray and Colorow, who spent the winter of 1866-67 camped near Balanced Rock in the Garden of the Gods. The story was told to a meeting of the Half Century Club in the 1920's; a synopsis has been preserved in the Kerr Scrapbooks at the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum:

"They did not bother us in Colorado City, and we felt no great alarm. They were more inclined to be friendly than otherwise. But one day a party of them came into town and made a demand upon us for 20 sacks of flour."They told us that they were nearly out of provisions and were in danger of starving. They said that they had come to ask that we give them the flour, but that so pressing was the need that if we were to refuse they would take it anyhow.

"The matter was talked over by the people of the town and not a person was found who did not think it the right thing to give them that for which they asked. It was the general belief that they were facing starvation and much sympathy was felt for them. So the 20 sacks of flour was presented and the Indians went away with it, grateful for the food."

Following the Indian Wars of the late-1860's, the Arapahoes and Cheyennes discontinued their visits to the Pikes Peak region. In the absence of their hereditary enemies, the Utes came to the Garden of the Gods in summer as well as in winter. One 1870's warm-weather visit was described by Chase Mellon in Sketches of Pioneer Life and Settlement of the Great West. Chase was the half-brother of Queen Palmer, who was in turn married to William Jackson Palmer, the founder of Colorado Springs. The Palmers owned an estate at Glen Eyrie, just up Camp Creek from the Garden of the Gods:

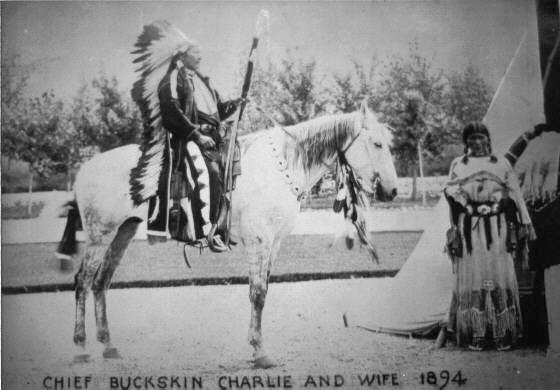

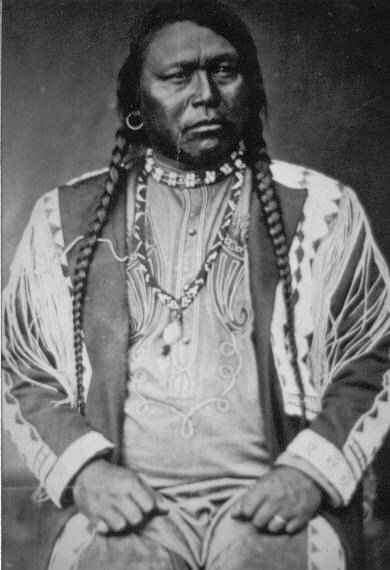

"Five hundred Utes with their squaws and papooses paid Glen Eyrie a visit that same year (mid-1870's). We understood that they were on their way to fight the Cheyennes, hereditary enemies. Perhaps they were choosing a place in safety in which to leave their old men, women and children and had often passed along the trail just outside our gates which led to Denver and the land of their enemies. They pitched camp and pastured their ponies in a cottonwood grove along Camp Creek within the limits of Glen Eyrie and less than a mile from the house. One never locked door or windows in the early days and it was no uncommon thing for my mother and others to be waked in the morning by Utes wanding through our rooms in perfect innocence, impelled merely by childish curiosity to see what sort of a wigwam the white man lived in."Chief Washington, an old chief of the tribe, was with the party and we feared no harm because he was then a friend of the Great White Father, whom he had visited in Washington and from whom he had received a silver medal, as large as a small plate, which he proudly wore suspended around his neck. We children were constantly at the encampment, and one day persuaded him in his wigwam, a little removed from the rest of the Indians on a slight eminence, as befitted his rank and dignity, to put on his headdress. As he did so his figure straightened up and he looked in spite of his great age, every bit the Indian in his feathered headpiece, its long feathered train reaching the ground, that one sees in picture books. Young Bill, a buck who in one of the last outbreaks of the Utes a few years later became a bad Indian, made us bows and arrows and taught us how to shoot.

"Once we and some of the grown-ups were invited to a feast. My eyes still smart at the recollection of the smoke-filled tepee. The meal was cooked over an open wood fire in the center and the smoke was supposed to find outlet in the aperture at the top. I well remember the look of the meat, dipped out of the pot and handed to each of us with great ceremony. We were bound to eat or be guilty of unendurable insult to our hosts. It looked the color of an elephant's hide and just about as tough.

"After the Indians had been with us for several weeks our elders thought it time for them to move on. So they called in former governors of the Territory. The pow-wow was most peaceful, ceremonious and flowery, and the Indians consented to go at Governor Hunt's suggestion that they should not impose further upon the hospitality of the white squaw. So one day we watched them take the trail for the north...Visiting the site of the camp after the Utes had gone, we heard a faint crooning and saw a feeble old squaw digging in the ashes of extinguished fires, searching for food. What became of her I do not remember, but she was not allowed to starve and die where the tribe had abandoned her."