|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

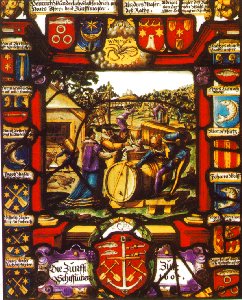

Heraldry is living survival of the great medieval world

of European chivalry. First introduced as a means of identification in

battle and tournaments, it gradually spread to society as a whole.

Today the knights in amour and many families who bore these coats of arms have disappeared, but heraldic tradition lives on in the royal arms, flags, emblems, road signs, sports badges and corporate logos of the modern world. Unravel the language and grammar of this social code that has been an inspiration for artists as well as an invaluable tool for historians, archaeologists and those interested in tracing their family tree... |

| Modern heraldry: from arms to logos

After a period of decline between the world wars, there has been a marked revival of interest in heraldic studies in most of western Europe over the past thirty years or so. University researcher and archivists are now showing more interest in arms than their predecessors. Moreover, thanks to the increasing use of computers they can greatly widen the scope of their research and investigations. But heraldry is not just the prerogative of scholars. It is also a part of everyday life. In some countries (Switzerland or Scotland, for example) there has in fact never been any break between medieval and contemporary heraldry: arms have continued to be displayed on many monuments and, over the centuries, taken up more and more space. |

|

|

In others, it is mainly the arms of corporate bodies,

especially cities, that continue to reflect the presence of heraldry in

everyday life. Today this urban heraldry is very much alive and has sometimes,

as in Scandinavia, given rise to highly original works.

However, the influence of heraldry is not just found on arms. It is also reflected in flags, direct descendants of the heraldry system - nearly all the flags of the world respect the heraldic rules on tincture combinations: in logos, which in some cases compete crudely with arms and are often based on canting charges, and even in road signs, designed as genuine arms that scrupulously respect heraldic rules regarding the use of tincture, both in Europe and world-wide. |

| The rules and composition...

Armorial bearings are made up of two elements, charges and tinctures, which are placed on a shield whose contour lines can take various shapes. The triangular form, inherited from medieval shields, is not obligatory, it is simply the most common. Some arms are inscribed in a circle, an oval, a square, a lozenge (frequently so in the case of women's arms from the l6th century in England) and there are even countless arms whose border is in fact the same as that of the object on which they are placed. If this object is a banner, the trappings of a horse or a piece of clothing, its border may also form the border of the arms. Within the shield, tinctures and charges cannot be used or combined at will. They obey a small number of binding rules of composition. These are the rules that most clearly distinguish European arms from types of emblem used by other cultures. |

|

In Asia, Africa, pre-Columbian America and the Muslim states we may therefore find at any one time, emblems that more or less closely resemble western arms, though they are never composed on the basis of a code of strict, unchanging rules.

|

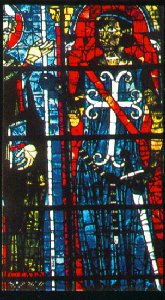

The Six tinctures of heraldry

The main rules of blazon relate to the use of tincture. This generic term covers both metals - Or (gold/yellow) and Argent (silver/white) - and colours - Gules (red), Azure (blue), Sable (black) and Vert (green). The first five can be found everywhere and are very common on the arms of all periods and all regions. The sixth, Vert, is less common, for reasons that have never been fully explained. There is also a seventh tincture, found even less frequently: Purpure (purple) not really regarded as a real heraldic tincture. |

These heraldic tinctures are absolute, conceptual. almost immaterial: the tones do not matter. For instance Gules can be vermilion, cerise, carmine, garnet red, etc.; what counts is the idea of red and not the material and chromatic representation of that tincture. The same applies to Azure, Sable and Vert, and even to Or and Argent, which can be rendered by yellow and white (as is commonly the case) or by gold and silver. For instance, on the arm of the King of France, Azure semy of Fleurs-de-lis Or, the Azure can be sky blue or ultramarine and the fleurs-de-lis lemon yellow, orange yellow or gold, it really does not matter. The artist is free to translate Azure and Or as he sees fit, depending on the material he is working on, the techniques he is using and his own aesthetic sense. In the course of time the same arms can therefore be represented in very different tones.

| The rules of blazon

Blazon arranges its six tinctures in two main groups - metals and colours. (There is also a third group, furs: Ermine and Vair.) It places Argent and Or in the first, Gules, Sable, Azure and Vert in the second. The basic rule is that a colour may not be placed on a colour or

a metal on a metal. To take the case of a shield depicting a lion: if the

field of this shield is Gules (red), the lion may be Argent (silver/white),

Or (gold/yellow) but

|

|

|

But these questions of visibiliry do not fully explain these rules.

They also date back to the very rich symbolism of tinctures during the

feudal period, a symbolism that was undergoing major changes at the time.

For the new social order that was becoming established in the West after

the millennium was accompanied by a new system of tinctures: white, red

and black were no longer the only basic tinctures as was often the case

in classical antiquiry and the late Middle Ages; blue, green and yellow

were now promoted to the same rank, in social life as in all the codes

relating to it. The emergent science of heraldry was one of these codes.

Whatever their origin, over the centuries these rules on the use of tinctures governed all the arms that were created. However, they were often infringed when two or more different arms were combined (or marshalled) within one shield and two tinctures that should in principle not touch each other necessarily became adjacent. When Edward III proclaimed himself King of France in 1337, he combined the arms of the two kingdoms on the same shield. In the new shield created by `quartering', the Azure field of the arms of France necessarily touched the Gules field of the arms of England. |

| The charges: an unlimited choice

Tinctures make up the essential component of arms. For although arms without charges do exist, there are none without tinctures, even though some arms are only known to us through monochrome documents, as seals or coins. But the range of charges that can be displayed on them is obviously much wider. It is unlimited: any animal, plant, object or geometrical form can become a heraldic charge. Over the centuries, new devices continually widened the range of choice. In our century, for example, several cities that have airports display stylized aeroplanes on their arms, while some winter sports resorts depict two Skis in saltire. Similarly, in the former USSR and Romania under Communist rule, several kolkhozy or collective farms were attributed arms decorated with combine harvesters or other agricultural machines. In these cases we are far away from the heraldic spirit. |

|

|

For although anything can be a heraldic charge, not everything is.

The range of charges normally used was in fact fairly small, at least until

the l7th century. During the decades following the appearance of arms in

the l2th century, it was confined to some twenry charges. Subsequently,

the number continued to grow; but until the end of the Middle Ages not

more than forty or so charges were in use. The range of choice became more

diversified in the l7th and l8th centuries in particular, first in the

Germanic countries and central Europe, then outside Europe, when other

continents began to turn to heraldry: exotic plants and animals started

to appear on shields.

For a long time it was fairly rare to find plants, except for the fleur-de-lis and rose, and everyday objects on arms. The charges encountered most frequently consisted, in almost equal proportions, of animals, geometrical figures (or ordinaries) resulting from the division of the shield into a certain number of bands or compartments, and small charges that were also more or less geometrical but could be placed anywhere on the shield: bezants, annulets lozenges, stars, billets and so on. At the end of the Middle Ages and at the beginning of the modern age, when the range became more diversified, it was primarily plants (trees, flowers, fruit, vegetables) and objects (arms, tools, clothes) that were added to the original charges. After that shields were charged with buildings, parts of the human body, letters of the alphabet and even actual scenes, which turned somc arms into small pictures that were illegible and contrary to the spirit of heraldry. |

| As the range of charges on which people could draw to create arms diversified over the centuries, so the number of charges placed on each shield increased. In the l2th and l3th centuries, there were generally only two charges per shield; in the l8th century it was quite common to place four, five, six or even more different charges on a shield, which was therefore divided up into several compartments. Over the generations the main charge was joined by several secondary ones. Family arms rarely stayed exactly the same: they often tended to become more complex with time, especially among the nobility. |  |

|

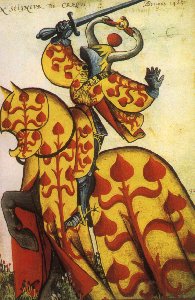

The eagle versus the lion

From the outset, animal figures were an essential and original component of heraldry. On a third of all arms, the main charge is an animal. The lion is certainly the most popular heraldic charge in every region, period and social class. Nearly fifteen per cent of European arms are charged with a lion - a little more in the Middle Ages, a little less in modern times. That is a considerable proportion, since the next charges in order of frequency, the `Fess and the `Bend', that is two geometrical designs or `ordinaries', account for less than five per cent. In fact, when arms became established in the course of the l2th century, the lion became the definitive king of the beasts in all the western traditions. Previously, the bear had been king in much of Germanic, Celtic and Scandinavian Europe. |

| The heraldic lion is always shown in profile, more often erect (rampant)

than lying down (couchant). In early English armoury, until the late 14th

century, any lion that was not rampant was called a `Lion leoparde'. This

term may date back to an ancient Greek convention that distinguished between

the lion, usually shown with a heavy mane and in profile, and the leopard,

which had less hair and was shown looking towards the observer. Later the

term leopard was applied only to the `Lion passant guardant', that is a

lion walking, with its right forepaw raised and its head facing the spectator,

as in the royal arms of England; hence the expression `the leopards of

England'. Nowadays, the term leopard applies only to the real animal, which

is rarely found in blazon.

After the lion comes the eagle, king of the skies and sometimes competing with the lion for the throne of king of the beasts - in modern times, in fact, empires have all chosen the eagle and not the lion as their heraldic emblem. In heraldry, the two animals are more or less mutually exclusive: in regions where lions are frequently displayed (Belgium, Luxembourg, Denmark, for instance) there are few eagles, and vice versa (Austria, northern Italy). The blazoned eagle is also rather unlike the real animal. It is shown Flattened, its body facing the spectator and its head in profile, with a very prominent beak and claws. The eagle appears on about two per cent of European arms, especially those of the nobility. |

|

|

From the real to the fantastic: the heraldic bestiary

Other animals occur less frequently and form a bestiary that has not changed for a long time. The stag or hart and the boar, the game , the aristocracy most liked to hunt, appear from the beginning, as do the bear and the wolf. The wolf is most common in Spanish heraldry. Domestic animals are more rare, appear later and are less common among the nobility. Dogs - recognizable by their collar - and cattle tend to be found more on peasants' arms in some countries on the Continent, while sheep can be displayed on the arms of towns and religious communities. The horse occurs in English heraldry, though on the Continent it is notable for its absence. Sometimes considered as a mere tool, sometimes as the equal of humans, it had a status of its own in early societies. Apart from the eagle, the main birds represented w on shields are the raven, the cock, the swan, a certain number of waders (cranes, herons, storks) and a few ducks, peacocks, ostriches and parrots. The dove and the pelican are found mainly on ecclesiastical arms. As for the falcon, it is as rare as the horse, although it was the bird medieval aristocracy preferred. But the bird most commonly seen on European arms is not real at all; archetypal and stylized, it cannot

be identified as belonging to a particular species. The heraldic term for

it is the martlet, although it has little to do with the martin. It is

a small bird, always shown in profile and generally repeated several times

on the same shield. It was represented without feet from the end of the

13th century and in France it was deprived of its beak from the Renaissance.

As used in heraldry, this bird looks more like a small geometrical devia

(star, bezant, lozenge) than an animal; it is often shown on arms in England,

northern France and the Netherlands.

|

| Much the same applies to a fish known as the pike (or luce). It

bears little resemblance to a real pike and is a stereotype fish, with

an elongated body; generally two fish are represented upright and back

to back on the shield. The pike is the charge most often borrowed from

the fish world. Equally stylized but more curvilinear and with an enormous

head and a kind of crop is the dolphin, which again bears little resemblance

to the cetacean of the same name.

Lastly, it should be noted that monsters, hybrid creatures (sirens, chimeras) and fabulous beasts (unicorns, dragons, griffins) are much more rare on arms than is generally believed. They only entered the bestiary and mythology of heraldry at a late date and in limited number. |

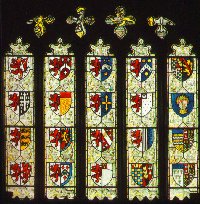

| The design and composition of coats of arms

The first arms had a simple design: a device of one tincture placed on a field of a different tincture. Since the arms were meant to be visible from afar, the design was schematic and any features that would help identify them were stressed or exaggerated: the contours of geometrical forms, the head, feet or tail of animals, the leaves and fruit of trees. The device occupied the entire field of the shield and the two tinctures, bright and clear, were associated according to the rules described earlier. These few principles, born on battlefields and at tournaments, formed the basis of the heraldic style, which every designer had to follow in order to remain faithful to the original spirit of heraldry. |

|

|

Over the centuries, however, amoral bearings tended to become more crowded and complex in their design. As we have seen, on family arms secondary charges were often added to the original one; or the shield was divided and subdivided into an increasingly large number of compartments, armorial', combining a number of different arms within the confines of one shield. These divisions expressed relationships, ancestry and marriages or displayed the ownership of several fiefs, titles or rights. Some modern arms have ended up being illegible as a result of being quartered again and again; the grand quarters of Queen Victoria could have 256 quarterings. |

| Once they became marks of ownership and began to appear on countless

objects of everyday life, arms became smaller in comparison to those displayed

on the banners and shields of the 12th-century combatants. Not only did

they become difficult to decipher but their artistic effect also declined.

In general the heraldic style, which reached its peak at the court of Burgundy

in the 15th century, became less inventive, more mechanical and also more

affected from the 17th century; it still showed some signs of vigour in

the Baroque art of Austria, Bavaria and northern Italy.

Elsewhere it was often cold and graceless, a victim of the theorists of heraldry who wanted to codify and lay down everything (composition, numbers, proportions) exactly, leaving no room for inventiveness and little for elegance. In the 20th century, however, several German (notably Otto Hupp), Swiss and Scandinavian artists have managed to restore to heraldic design the simplicity and force of expression it had in the Middle Ages. |

|

|

Deciphering arms

Apart from quartering and the frequent combination of two arms on a single shield, another essential feature of armorial composition is its depth. Several levels are piled one on top of the other and they must be read starting from the lowest level. In fact, that is how , most medieval images must be read, especially those from the late Romanesque period, when arms first appeared: first the lowest level, then the intermediary ones and finally the level nearest to the spectator's eye - an order that goes against the grain today. When designing armorial bearings, artists first choose a field, then charge it with a device; if they want to add other features they have to place them on the same level as the charge or - as frequently happens superimpose a new level; it is impossible to go backwards. So the shield can be regarded as made up of a series of levels: the lowest represents the original structure and the main charges of the arms; the middle and top ones are charged with successive augmentations and help to distinguish between, for example, two branches of the same family or two individuals from the same branch. |

| The crest: mask or totem?

The shield is the essential element of heraldic composition. In the strict sense of the word, it bears the arms. In the course of time, however, accessories were added to this shield, some purely decorative (helmets, coronets, mantling), others serving to indicate the identity, rank, office or dignity of the owner. But on the Continent these external elements were never governed by rules (though they were in England), unlike the tinctures and charges on the shield proper. The earliest external ornament is the crest on the upper part of

the helmet. Its origins go back as far as classical antiquity, where its

function was military: to frighten the enemy, to make the combatant look

bigger and to attract beneficial forces towards him. At the end of the

Middle ages it became mainly a ceremonial piece of decoration: worn at

tournaments, rarely at war, it was a fragile structure of wood, boiled

leather, canvas and plumes. When depicted on paintings or monuments, the

crest above the shield was never represented realistically; sometimes it

took on considerable proportions; sometimes it grew in number. For example,

during the Baroque period, a shield divided into four quarters were even

given four different crests.

|

|

|

Over the centuries, in fact, the crest decoration on the helmet,

which at first was individual and could be changed at will depend on circumstances

or the whim of the user, tended to stay the same and become hereditary

within one family. It could then repeat a charge displayed on the shield

or, more frequently, consist of another charge.

In Germanic countries, family crests became established very early on and were often an essential part of the shield. In Poland and Hungary the crest often acquired a totemic function, with all the members of a family group using the same crest and the name of that crest being used as the surname of the entire dynasty. Elsewhere, crests were used more flexibly and intended for display purposes, although many of them eventually became hereditary. In England, for example, shields became so heavily charged and complex in the 18th and 19th centuries that the crest was often used more frequently than the arms. |

| Collars, insignia and other devices

Other external ornaments include the `supporters'. They first appeared on seals in the course of the 14th century and are made up of animal or human figures what appear to be holding up the shield. They have been used more widely in modern times but remain ornamental, even though some families have always tried to use the same supporters. Conversely, the collars of orders of chivalry and the insignia of office and rank (episcopal cross, crosier, sword belonging to a constable) are personal and significant. They help identify an individual when i he armorial shield itself only indicates the family a and they can often provide a certain amount of data on the life or career of that individual. The many coronets that surmounted shields from the 17th century are, on the whole, decorative. There are five coronets of rank that may surmount the arms of English peers. Finally, from the end of the Middle Ages, a motto, in the modern sense of the term, would sometimes be added to the shield. It could be a single word, derived from the war cries of feudal times, or an entire phrase. The mottoes were generally inscribed on a scroll or ribbon. Some are individual, some belong to a family or community. The same individual or family could have several mottoes, while the same motto could be common to several families, communities or unrelated individuals. |

|

|

|

|

|

|