| MILESAGO - Groups & Solo

Artists |

| The

Dave Miller Set |

Sydney 1967-70, 1973

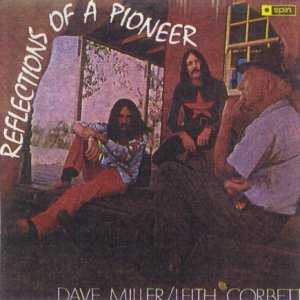

A

1968 publicity shot of the DMS, which was also used on the cover

of the Hope EP

L-R John Robinson, Ray Mulholland, Dave Miller, Bob Thompson

Harry

Brus

[bass] 1967

Leith Corbett [bass] 1969-70

Mick Gibbons [guitar] 1967

Greg Hook [keyboards] 1967

Mike McCormack [drums] 1969-70

Dave Miller [vocals, guitar] 1966-70

Ray Mulholland [drums] 1967-69

John Robinson [lead guitar] 1967-70

Bob Thompson [bass] 1967-69

The Dave Miller Set is an important group

in the history Australasian music and one that has been long

overlooked for much too long. They were one of the most popular

and hard-working live bands on the east coast scene in the late

'60s. They are still fondly remembered for their classic psychedelic

single Mr Guy Fawkes, which was Go-Set's Single

of the Year for 1969, but they are significant for several other

reasons, not least the emergence of guitarist and composer John

Robinson, one of Sydney's original 'guitar heroes', who went

on to further fame with Blackfeather and also became

an influential guitar teacher.

Most importantly,

the DMS was a key chapter the career of New Zealand-born singer-songwriter

Dave Miller, a performer as remarkable in his own right

as was his group. Dave is a crucial link between the formative

music industries of Australia and New Zealand. He honed his craft

in thriving Christchurch scene and since they were teenagers

he has been a close friend and colleague ofmost of the top New

Zealand acts of the era including Max Merritt, Ray

Columbus and Dinah Lee.

The DMS career

spans the fascinating transitional period from the end of the

"scream era" in 1967 to the start of the infamous Radio

Ban in 1970. They were one of the first Australian acts to pick

up on the heavy rock/progressive rock trend pioneered by overseas

acts like Cream, Hendrix, Free and Led Zeppelin, a direction

which was developed after 1970 by groups like Kahvas Jute, the La De Das and Blackfeather.Their style was

forged on Sydney's university and college circuit, and in the

thriving inner-city club scene that was fulled by the influx

of American servicemen on "R&R" leave -- just as

Dave's hometown of Christchurch had been 'revved up' several

years earlier by the arrival of American personnel as part of

"Operation Deep Freeze". The DMS and the other groups

that played around Sydney at that time are not well remembered

today, but their various members went on to form some of the most

notable bands of the early 70s -- Mecca became Kahvas Jute, Gus & The Nomads evolved into Pirana, Levi Smith's Clefs

spawned no less that three bands Fraternity, Tully and SCRA, and the DMS itself of

course became Blackfeather. Despite a solid following throughout

NSW and in Queensland, the DMS were victims of the infamous Sydney-Melbourne

rivalry and they were almost completely ignored in Victoria --

Stan Rofe was the only Melbourne DJ who played them -- and unfortunately

they never managed to establish a national presence.

As with his

first band Dave Miller & The Byrds, Dave handled virtually

every aspect of the DMS business affairs, and his entrepreneurial

skills guided them to considerable success in Sydney, in New

Zealand and even as far afield as Fiji, and it would be

difficult to name another local self-managed act of the period

that achieved anything like the same success. As somoene with

considerable experience and ability in this area, Dave's first-hand

observations on the management (at that time or the lack thereof)

are also of great interest. Another important thread is Dave's association/collaboration

with influential industry figures -- Eldred Stebbings, Ivan Dayman, Graham Dent, Nat Kipner and Pat Aulton. Dave moved easily in industry circles,

had a good rapport with the media, was a tireless promoter and

organiser on behalf of his band, and his collaboration with Festival

house producer Pat Aulton created some classic recordings.

The five

records that The Dave Miller Set recorded for the Spin label

are among the freshest and most enjoyable Australian pop-rock

singles of the late '60s. Little-known, and too long out of print

(come one, Festival, what's the story?) they are genuine classics

of their kind. All were produced, arranged and included vocal

and instrumental contributions by the great Pat Aulton,

one of the most prolific, influential and talented producers

of the period. The development of the partnership between Pat

and the band is engagingly snapped in the sequence of records

-- their 'Animalistic' debut Why, Why Why, the confident,

optimistic strut of Buddy Beui's Hope (their first hit

single), a superb version of The Youngbloods' Get Together,

their psychedelic masterpicece Mr Guy Fawkes, and the

lost piece of the puzzle, their ill-fated cover of Chicago's

Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is? It might otherwise

have been a transitional single, but which disappeared into the

black hole of the Radio Ban, effectively marking the end of the

group's career.

These ten

sides are also a testament to the band's professionalism, creativity

and efficiency as a performing unit. All were done in one or

two takes, and Dave reckons that they would typically knock off

both sides of a single in a single three-hour session. Dave's

bright, clear tenor voice suited a wide range of material, and

the variety of styles in which he could perform is a tribute

to his versatility. They chose the A-sides well, playing to their

strengths, and the arrangements feature plenty of invention and

just plain good fun. There's a freshness and sincerity, the essence

of the good-time spirit of the DMS, in all of them. They are

also a great illustration of one of our recurring MILESAGO themes

-- how Australian bands recorded cover versions of lesser-known

overseas songs that were in most cases far better than the originals.

The B-sides offer a glimpse into other facets of the band's repertoire,

and in the absence of live recordings, No Need To Cry

(the B-side of their last single) is about as close as we're

likely to get to what the DMS actually sounded like at their

peak as a live band, as well as chronicling two of Dave's earliest

songwriting efforts.

We hope this

account will go some way to rectify the previous lack of information

about Dave's career before, during and after the DMS and to correct

some of the misnomers abut the band. For more detail about Dave

Miller and the DMS we exhort readers to read transcript of the

excellent Dave Miller interview by our friend Steve Kernohan.

We are profoundly grateful to Dave Miller, John Robinson and

Pat Aulton for their generous cooperation over many conversations

and interviews.

Well before he came to Australia, New

Zealand-born Dave Miller was already a significant figure in Kiwi

music, fronting one of the best NZ 'beat' outfits of the period,

Dave Miller & The Byrds. Dave grew up and began his

career in the fertile musical scene of Christchurch in the late

50s and early 60s, the city that also gave birth to Max Merritt & the Meteors,

Ray Columbus & The Invaders, Dinah Lee and more recently singer Bic Runga and pop heartthrobs ZED.

In his teens Dave became close friends

with both Ray Columbus and Dinah Lee, and like so many young hopefuls

in the City of Churches, he and his friends all looked up to the

example of Christchurch's No.1 musical son, the great Max Merritt.

With teenagers everywhere, they were smitten by the first wave

of rock'n'roll -- Elvis, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, Chuck

Berry, Buddy Holly and The Everly Brothers, whom Dave as a teenager

saw when they toured New Zealand ca. 1960. Dave also nominates

Cliff Richard & The Shadows as a crucial influence

on almost every local band of the time, and in that pre-Beatles

period, "The Shads" were for quite some time the

model of how a group should look, sound and act. But most of their

early first-hand experiences of rock came from the pioneering

"downunder" rockers -- Australia's Johnny O'Keefe, New

Zealand's Johnny Devlin, and of course Max, whom Dave counts as

one of the best performers ever to emerge from the local scene.

A feature unique to Christchurch in the early '60s was the

influx of American personnel who passed through the city as part

of "Operation Deep Freeze", the establishment of the

American Antarctic base. Christchurch was chosen because it had

the only airfield in the region big enough to accomodate the huge

US military transport planes that ferried staff and equipment

to and from the base. The American influx gave the Christchurch

scene a special "leg up" and it many respects it became

the "Liverpool of the south", thanks to the infusion

of original blues, R&B and rock'n'roll records brought in

by the Yanks, as well as the Fender guitars that were so highly

prized at the time (thanks to The Shadows) and so hard to come

by in other places. Another more personal musical influence was

Dave's friend Hoghton Hughes who worked in a local record

shop and whose access to rare import singles introduced Dave to

many classic records of the period by original artists like Jimmy

Reed and Chuck Berry.

The credit for Dave's start in music

actually belongs to his younger brother Graeme Miller,

who also developed a passionate interest in rock'n'roll and took

up drums in the early '60s.

Dave: My brother went out one day

and came home with a drum kit - as simple as that! Set it up

in the lounge room... and taught himself to play drums. Quite

quickly, in point of fact.

Graeme joined his first band The Numonics

in early 1962. They often supported another popular local group

led by Maori singer-guitarist Pat Nehoneho, The Saints,

which was fronted by dual vocalists Phil Garland and Diane

Jacobs. Pat liked Graeme's playing and he recommended him

to Phil and Diane when they put together their own band after

The Saints broke up. This was The Playboys, with Graeme

on drums, bassist John O'Neill, lead guitarist Brian

Ringrose (who had just left Ray Columbus & The Invaders),

Mark Graham on rhythm guitar, Phil and Diane -- who was soon

to be famous in her own right as "Dynamic" Dinah

Lee.

The Playboys often rehearsed at the Miller

house, and Dave sat in and sang with them on many occasions, although

he was yet to perform publicly. By this time that Dave was already

good friends with Ray Columbus, whose with his band The

Invaders were already one of New Zealand's hottest bands and would

soon to set the Australian charts on fire with their classic hit

She's A Mod. Original Invaders lead guitarist Brian Ringrose

was classically trained and already a well-rounded musician, but

he had left the Invaders when they moved up to Auckland (at the

same time as Max Merritt) preferring to stay behind in Christchurch

and complete his tertiary entrance certifcate.

The Playboys quickly built up a solid

following in the Christchurch area. In late 1962 they were invited

up to Auckland for six weeks to deputise for The Meteors at Auckland's

Top Twenty club while Max and the band were away on a national

tour (just before their first trip to Australia). This was not

uncommon practice, Dave says -- resident bands in Auckland would

often bring in a "locum" group from a regional city

like Wellington or Christchurch while they were away on tour,

and the substitutes could then be packed off home when they returned,

without the risk of losing their spot. But while The Playboys

were in Auckland, Dinah was spotted by leading NZ guitarist Peter

Posa. He came back the next night with Ron Dalton

of Viking Records, New Zealand's major independent label. Dalton

immediately offered Phil and Dinah solo contracts and even before

the Top Twenty gig had finished they had announced their intention

to leave the band.

Obviously The Playboys were going to

need a new singer fast, but the solution was close at hand: Dave

had sat in with the band at many rehearsals, he was familiar with

the repertoire ... and he could sing. Dave's "call-up"

into music came in the form of a classic telegram from his brother

in Auckland, which read:

GIVE UP SMOKING. START

LEARNING SONGS. YOU'RE OUR NEW SINGER.

The Playboys/Dave

MIller & The Byrds

Dave's debut with The Playboys in early 1963 was a baptism of

fire -- he had to follow "Dynamic" Dinah onstage at

her farewell gig in Christchurch:

Dinah did her farewell, and I followed her

immediately onstage and did about four numbers at this big venue

called The Caledonian Hall. ... it was a huge, big crowd, and

I can tell you, I hardly slept for the week prior, I was that

damn nervous!

Luckily, Dave proved to be a natural

showman and a great addition to the group. This new lineup comprised

two sets of brothers -- Dave and Graeme Miller, John O'Neill and

his younger brother Kevin-- plus Brian Ringrose. Kevin O'Neill

had replaced Mark Graham, who gave up performing to work in his

parents' hotel business shortly after Dave joined.

It was not long after this that Dave's

friend Hoghton Hughes gave The Playboys their first break:

We did all the various gigs around, and I

was very closely friendly with a chap called Hoghton Hughes.

Now Hoghton, if you don't know, is the brains trust behind the

MusicWorld conglomerate out of New Zealand and Australasia

-- the budget music label. When I first met Hoghton, he was working

in an electrical shop that had record sales -- the predominance

of course was the little old 45s -- and I found he was the most

hip bloke in town, so I used to buy my records there, and and

as a consequence of that we got very friendly.

The reason we took off so significantly in

Christchurch -- and when I say took off, it just absolutely skyrocketed

-- was the fact that there was an elderly gentleman, his name

was Ridings, and he ran a very old-fashioned dance hall and it

was called The Latimer. Christchurch has a number of squares

and boulevards, and this place in Latimer Square had been going

for years. But he decided, on the advent of Merseybeat, that

he might try and embrace something a bit more modern. They'd

built a new big hall in the centre part of town, just beside

the Avon River, the Horticultural Society Hall and he got the

licence to be able to put live entertainment in there, dancing,

etc, ... and he called it The Laredo. And he used to buy

his records from Hoghton Hughes, and he said to Hoghton: "Who

would be the best band in Christchurch to put in a venue like

that?" And Hoghton, knowing me and knowing what we were

all about and liking the band also, said there's only one to

even contemplate and that was The Playboys. So this bloke got

in touch with me, and we did it, and we pulled capacity crowds

into that place -- they used to queue on the street.

The Playboys settled into a hugely successful

residency at The Laredo, which ran from late 1963 to late 1964.

It was a heady period for the young musos, who by that time were

earning as much eight pounds per week each from gigging-- pretty

impressive, considering that the average weekly wage back then

was only around ten pounds!

In June '64 Beatlemania took Australia

and New Zealand by storm, and Dave and the group were among the

thousands who flocked to see the Fab Four play in Christchurch.

After seeing the matinee show, The Playboys played their regular

gig that night at The Laredo. Dave revealed that, in one of those

great "couldabeen" moments, they managed to contact

to members of the Fabs and their entourage by phone at their hotel

after The Beatles' second show. Things even got to the stage where

a couple of the Beatles agreed to come over to the Laredo to join

the Playboys onstage for a jam, but the plan was foiled because

the Christchurch police would not provide security for the trip

between hotel and venue!

The Playboys might have remained a local

attraction but they got a crucial break in late 1964, which soon

set them on the road to national prominence, when they were spotted

by Howard

Morrison. Howard is part of a famous

New Zealand family -- his father Tem was an All-Black, Howard

himself (now Sir Howard) is an elder statesmen of New Zealand

music and one of the country's best-loved entertainers, and his

son is actor Temuera Morrison of Once Were Warriors

fame.

At the time that they met, Howard was

the leader of the hugely popular vocal group The Howard

Morrison Quartet which had been one

of New Zealand's top attractions for almost a decade. Howard and his agent Benny Levin caught a Playboys

gig one night when they were in Christchurch, and they were impressed

enough to invite them to be the Morrisons' backing group on their

upcoming summer tour of NZ holiday resorts.

This was to be a special event, and the engagement of the Playboys

-- a typically generous act by Howard -- was

the turning point in their career. Although Harry M. Miller was

keen to take them overseas, Howard was reluctant to leave home

and family so he had decided to break up the goup. They were about

to embark on their farewell tour, the last of the hugely popular

"Summer Spectacular" concerts, promoted by their manager,

Harry M. Miller, that had played to hundreds of thousands

of new Zealand holidaymakers in previous years. It was, as Dave

aptly puts it, "big bikkies to a little band like us!".

The tour contract was purely verbal,

but Howard was as good as his word in every respect. His example

inspired Dave in his own career and he still speaks of Howard

in glowing terms:

We were taking a risk of a lifetime, bearing

in mind that the average age of the band was only about 18 at

that time, and we had the families absolutely shaking in their

boots about what we were doing. We could have been left high,

dry and stranded, and it be the archetypal rip-off.. Howard's

one of those people whom I have a great admiration for, because

all the terms he nominated to me were all spoken, and they were

sealed with a handshake, but he never, ever once

let me down in any capacity. Paid everything, did everything

-- his word was his bond, and I admire that implicitly.

The Playboys went first to Auckland,

where they were provided with a house, then on to Roturua for

pre-tour rehearsals. Just before they set out they decided to

change their name to The Byrds, to avoid confusion with

other acts like America's Gary Lewis & The Playboys, and Normie Rowe's backing

band of the same name. According to Dave, the change came

some time before the famous American band of the same name had

their first hit. That in turn necessitated the later addition

of "Dave Miller & .." prefix.

Over that summer the Byrds and the Morrison

Quartet played to literally tens of thousands of people, an experience

which thoroughly honed their playing and showmanship. The Morrisons'

had broad family appeal and performed a commensurately wide range

of material, which The Playboys had to learn quickly and throroughly;

the repertoire for the tour comprised at least 50-60 songs, according

to Dave, on top of their own material. Bolstered by Brian Ringrose's

classical training, they rose to the task. Morrison was a consummate

showman who demanded the best from them, and the band all learned

a great deal from the experience. A double live album was recorded

during the tour, which climaxed with a New Year's Eve concert

in Howard's home town of Rotorua.

When the tour finished and Dave &

the Byrds hit the Auckland club circuit in early 1965 they were

red hot, one of the most polished and entertaining pop acts in

the country. They quickly snared the residency at the poular Shiralee

(later The Galaxie), a slot that had just been vacated by Dave's

old mate Ray Columbus, and they were soon pulling in big crowds.

In another typically generous gesture,

Howard and Benny Levin recommended the Byrds to Eldred Stebbings,

owner of the Zodiac label. The association with Stebbings

was not a particularly congenial one, although the singles themselves

are fine recordings, given the primitive facilities available

to Zodiac, and much of the credit for this is due to Zodiac's

engineer, John Hawkins (who also did some great work with

The La De Das).

Dave and The Byrds scored a major hit

in Auckland 1965 with their debut single, a strong cover of Jimmy

Reed's Bright Lights Big City, a favourite song that he

had discovered back in Christchurch via his friend Hoghton Hughes.

It was Top Five hit back home in Christchurch and in Wellington,

and peaked at a very creditable #13 nationally. It was backed

by a cover of Little Lover, a Graham Nash song originally

cut by by The Hollies, who were a major influence in NZ

at the time, as they were in Australia on groups.

They also charted in several cities with

their follow-up, How You've Changed. It was backed

by a rocky cover of Wake Up Little Suzie, by Dave's old

faves The Everly Brothers.

Because Bright Lights, Big City had

done so well, I beleived that I was right being in blues territory.

I was comfortable with that. So for the second single I chose

a song called How You've Changed. Now we've been credited

with borrowing that from The Animals, or from The Yardbirds --

and that is rubbish as well. I have an album to this day, which

I got from Hoghton Hughes in the late Fifites, called One

Dozen Berrys, by Chuck Berry, and it's on that.

The flip side was a very rocked-up version

of The Everly Brothers' Wake Up Little Suzie. A strange

sort of coupling, in retrospect, but we gave it that sort of

Jimmie Reed/Chuck Berry 'chunka-chunka' rhythmic feel, as opposed

to country. And we belted the hell out of it, and it was a major

hit in places like Rotorua. It hit the Top Ten there, and they

didn't want to know about the other side.

The breakthrough success of Bright

Lights had enabled the band to work outside Auckland, and

they made regular trips to neighbouring towns like Hastings, Gisborne

and Napier. It was also in this period that Dave began to blossom

as a self-managed performer:

The smart turkey in me had realised -- why

was I hanging around Auckland for twenty quid a week? Why didn't

I run my own shows? And I burned the candle at both ends, out

in the middle of the night, 2, 3 and 4 o'clock in the morning

pasting up posters, being at newspaper offices the next day pestering

away for press, being at radio stations and sitting in on the

radio stations making sure they played the single twice. All

of those things. That's why I didn't end up finding a manager

in Australia either...

Not long after the second single came

out in mid-'65 the O'Neill brothers decided to leave for personal

reasons. Dave replaced them with rhythm guitarist Al Dunster

from leading Auckland group The Dallas Four, and Liverpool-born

bassist Chris Collier, who had come from a band in Napier.

This last lineup cut one more single, the rather gimmicky

No Time backed with another Everly's number, Love is

All I Need:

I was listening to a pile of import things

at Eldred Stebbings' place, and I heard this thing -- No Time,

it's called, and it was by Dave, Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick and Tich,

and it was their very first single, before they broke through.

It was in 3/4 time, and it's based around the chimes of a clock.

And I thought "There it is -- it's got it's selling feature"

And in pockets it did good things for us as well.

Their final recordings were released as a self-titled five

track EP that is now a prized NZ collector's item. Dave describes

the five tracks as a pretty representative slice of the sound

and style of their sets at that time. It was recorded completely

live in the studio, warts and all.

There's the old blues standard Help Me,

based around the "Green Onions" thing; Ain't Got

You which The Yardbirds and The Animals covered, and I think

we might have been inspired more by The Animals. There was an

old Johnny Otis standard, called Tough Enough -- we did

a very good version of it but we originally got it from Cliff

Richard & The Shadows. We went down their standard arrangment

route, but that time it had become such a workhorse it was much

more 'lead-booted' than they would have done it. And then there

was a verison of Buddy Holly's That'll Be The Day, that

had been inspired more by the Everly Brothers, off that Rock'n'Soul

album that I told you about. And then we did what I suppose would

best be described as "Pretty Things" type arrangement

of the old Fats Domino standard Let The Four Winds Blow.

Dave and Brian had also begun writing together around this

time, and they made some private demos of the songs they wrote

but it wasn't until he moved to Australia that Dave's original

material began to be recorded. Happily these first demos still

exist (along with some other exceedingly rare and important NZ

recordings) in the possession of Brian Ringrose.

Dave is nothing if not a realist, and

by 1966 he could see that even though the NZ scene was booming

and The Byrds were doing extremely well, any further local success

would be limited, and that they'd soon be going over old ground.

By this time The Invaders, Dinah Lee and The Meteors had all crossed

the pond and were enjoying varying degress of success. Australia

was the obvious next step for The Byrds, as it was for any ambitious

NZ band -- although Dave says he was seriously considering trying

his luck in Hamburg. Al Dunster, who had already crossed the Tasman

with The Dallas Four, was keen to try Australia again (and his

girlfriend was there too). But the rest of the group were reluctant

to move and start all over again -- Brian Ringrose, for one, had

been performing since he was a child, and he didn't relish the

prospect of having to start all over again in a new country. He

stayed at home and is today one of the most respected musicians

on the NZ scene.

The Byrds honoured their outsanding commitments

and went their separate ways in early 1966. Dave is insistent

on one point -- the Byrds did not go to Australia and become

the Dave Miller Set, as most accounts have stated. Only Al and

Dave went over and while they remained friends, they never worked

together again professionally after the Byrds.

Dave did a few final solo gigs, then

he prepared to go over to Sydney. He naturally wanted to further

his career, but there was another especially compelling personal

reason for the trip -- his fiance Corinne (whom he had met in

Christchurch two years earlier while performing at the Laredo)

had just moved to Sydney with her family.

Australia and The Dave Miller Set

Al Dunster travelled to Australia first, soon followed by Dave who arrived in Sydney in April 1966. Through

Al's friendship with the manager there, Dave scored a job at the Sydney CBD venue The Bowl in Castlereagh St, part of the pop empire run by influential manager-promoter Ivan Dayman, whose Sunshine agency and record label was home to many leading

mid-60s acts and whose roster included Normie Rowe, Peter Doyle,

Mike Furber and Tony Worsley and Blue Jays. Sunshine also ran

venues like The Bowl (where The Easybeats had one of their first

residencies) and Brisbane's famed Cloudland

Ballroom. The manager of The Bowl, Graham

Dent, was himself an Kiwi expat and when Dave arrived in Sydney Graham's main job was as the manager of Dave's old mates Max Merritt & The Meteors. Needless to say, Graham knew of Dave's achievements in New

Zealand and hired him on the spot.

Dave worked for several months at The

Bowl and other venues as MC, introducing Sunshine acts like Normie

and Peter Doyle, and performing as a DJ and solo singer. While

not as cretively fulfilling as his previous work with the Byrds,

this period proved important for Dave in making connections on

the Sydney music scene, particularly Spin

Records boss Nat

Kipner.

In that fluid period at the end of the

"scream era" Dave says he seriously considered the idea

of leavng the pop scene and moving into the lucrative club circuit:

I wasn't sure which way to go, because even

people like a youthful Doug Parkinson, at that stage ... they

were sort of flailing around doing all sorts of semi-clubby type

things ... none of us competely knew exactly what to do...there

were lots of other people, like Digger Revell, they were making

a real living out of it. I nearly got caught up in it. I kept

thinking "I owe it to my fiance, I owe it to myself'.

What drew him back into the pop scene

in late 1966 was Dayman and Dent's decision to revamp The Bowl

as a discotheque and rename it the Op-Pop Disco. Dave was

asked to put together a house band, so he contacted an old friend

from New Zealand, drummer Ray Mulholland, (ex- The

Rayders) who was keen to come over and

work in Sydney. Dave then recruited a promising young bass player,

Harry Brus (ex-Amazons) who went on to become a longtime

backing player for Renee Geyer and one of Australia's most respected musicians.

The lineup was completed by guitarist Mick Gibbons (ex-The

Bluebeats) and keyboard player Greg Hook (who later worked

with Respect, Odyssey, Stevie Wright and Lindsay Bjerre), thus

creating the first lineup of The Dave Miller Set.

Unfortunately, by the time Dave had put

the new group together Dayman and Dent had changed their minds

about the house band, and a rather disgruntled Dave had to scratch

around for other opportunties. The Set's first major gig proved

to be an important showcase, and the turning point for the new

band's future. They were hired as part of a package show headed

by Johnny Young &

Kompany and Ronnie Burns, at the Sydney

Royal Easter Show in March 1967. The DMS (minus Dave) backed Ronnie

Burns and Dave rejoined them for their own sets. Because Greg

Hook was unavailable for the gig (he had a day job) Dave decided

to add a friend of Harry's as second guitarist for the duration

of the Show -- teenage guitarist John Robinson, formerly

with Sydney outfits The Lonely Ones and Monday's Children.

Harry (who was already becoming something

of a favourite with the girls) acquired his own small 'fan club'

at the Show, who followed him around and called out his name during

the sets. At one point they started up their chant of "We

want Harry!" during Johnny Young's set, prompting "Mr

Nice Guy" Johnny to yell back: "Who the f*** is Harry?"!

Harry also has a precious segment of Super-8

footage that was taken the group (without Dave unfortunately) were playing with Ronnie Burns, which is probably the only remaining visual record of this original lineup.

After the Easter Show gigs, the band

broke up for short time while Dave went back to New Zealand to

marry Corinne. He felt he had discharged his obligations to the

members of the group, and now married, he knew that he could make

far more money as a solo artist on the club circuit. He had no

definite plans when he got back to Sydney, but he had no chance

to make any -- the rest of the band approached him almost immediately,

anxious to reform and keep going.

So Dave reconstituted the group, but

Mick Gibbons and Greg Hook didn't rejoin. Having one fewer mouth

to feed made life a little easier financially, so he kept the

Mark II DMS as a four-piece with Harry, John and Ray. This second

lineup was shortlived though -- John was keen to work with his

former Monday's Children bandmate, English-born bassist Bob

Thompson, and it wasn't long before Bob was brought in to

replace Harry.

When the DMS first formed they played

much the same repertoire as The Byrds including covers of The

Yardbirds, The Kinks, The Animals and other poular favourites.

The first lineup made no commercial recordings, although they

did tape three demo tracks (which Dave still has) at a studio

in Manly Vale run by Bruce Brown, with the late Duncan

McGuire engineering. Brown became the house engineer at Albert's

Studios in Sydney in the '70s and '80s, and McGuire the renowned

bassist in Doug Parkinson In Focus, Friends, Ayers Rock and the Southern Star Band among others.

By the time Bob Thompson came on board

in late '67, there were big changes happening in music overseas,

especially the emerging UK acts like Cream and The Jimi Hendrix

Experience. As John found his feet

in the band they gradually adopted this "heavier" style,

becoming one of the first Australian bands to do so, although

this transition was made technically possible by Dave's entrepreneurial

skills.

John was already a proficient player

-- his original ambition was to be a jazz guitarist -- but he

was yet to develop into the guitar wizard he would soon become,

and Dave worked assiduously on developing John's stagecraft and

showmanship. Over the next three years Dave provided John with

the space and scope to develop into one of the most powerful and

innovative electric guitarists on the scene, in the tradition

of players like Clapton and Peter Green. It's certainly not unreasonable

to suggest that Dave can be considered as an Autralasian equivalent

to John Mayall.

One immediate and important effect of

John's arrival was to help change the musical direction of the

DMS at this crucial time in rock music:

John: I happened

to be at Nicholson's Music Store one afternoon and picked up

two new releases: Strange Brew by Cream and Hey Joe

by Jimi Hendrix. Cream were good and I'd heard Clapton before

with John Mayall and the Yardbirds, but Jimi was another thing

altogether. Stone Free, the B-side was a good example

of what a small group could do, and after playing both records

to the guys, we all agreed that this was the direction to go

in. By the New

Zealand tour of Xmas '67, we had most of the Hendrix and Cream

releases covered.

Dave too was always on the lookout for

new sounds (he would later introduce the band to Led Zeppelin)

and clearly these records had a big effect. Their significance

to the band and the period was immortalised by Dave when he namechecked

both Strange Brew and Stone Free on their version

of Sam Cooke's Havin' A Party, the B-side of their second

single Hope.

The Bowl period proved frustrating in

some respects, but it paid off in other ways. As mentioned previously,

it enabled Dave to make connections with important people on the

Sydney music scene, and the friendship that developed between

Dave and Spin Records boss Nat Kipner, (father of Steve

& The Board's Steve Kipner) led directly to the DMS

being signed to the label. Kipner teamed them with Pat

Aulton, who is justly famous for

the many classic discs he produced for Normie Rowe, Kahvas Jute,

Neil Sedaka and many others. It was a to be happy and productive

partnership, and Pat produced and arranged all of the band's singles

was well as contributing backing vocals and additional instruments.

As with Howard Morrison, Dave is unequivocal in his admiration

and respect for Pat, whom he compares to George Martin:

Pat was one of the most complete and comprehensive

people I've ever met. In the beginning perhaps he wasnt so sure

of me, but by the time we got through No Need To Cry and

Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is, we were very

close friends. We'd socialise together and do all sorts of things.

The admiration built over time, but my admiration for him was

profound right from the very beginning.

He was very interesting. He fascinated me.

It found it a bit daunting at first, being a totally self-taught person. He could play keybords ... he'd been on television and played keyboards and sung .. he could really sing. He

was great with harmony, he knew how to arrange, he could orchestrate, he could do all those sorts of things. If Pat was in control, a good job was going to be done. I've been in the studio and they'd be putting down backing tracks and he'd say "Hang on, John -- the G-strings's gone flat". He was able to hear all those things, all those nuances.

MILESAGO was also privleged to talk to

Pat recently about his work with the DMS. His comments about them

echo Dave's admiration for his former producer, and he

also offered some fascinating insights about the DMS recording

sessions and his working methods at the time.

Dave was a very diligent young

man, very enthusiastic. He had a very good ear. We got on extremely

well, extremely well. They were all very fine players, very efficient

in the studio. I just kept them in tune (laughs). They were quite

a joy to work with.

I don't believe in doing things over and over,

like a lot of people do -- you just end up losing the plot. It's

all about art and design. If you're designing a piece of music,

you've got to get everything right before you roll the tape.

We always worked very hard, setting things up, rehearsing, getting

the sound and making sure everyone was right in the spirit of

the thing. If you prepare thoroughly, you can usually capture

it pretty quickly. Dave and the band were good at that and you

can hear the results on those records -- they have a lot of sponteneity.

I can be a taskmaster, and perhaps someof

them found it bit frustrating sometimes, but ultimately it paid

off. I took a lot of time getting the sound just right. With

the drums, for example, I used to tune them myself. I'd tune

them in key, to the first the third and the fifth, and I'd always

be calling for "more dampening, more dampening" on

the snare or on the toms, to get a 'thicker 'sound. Another thing

I remember was that I never had to do much with Bob Thompson's

sound -- he always had that pretty right himself, he knew how

it should be.

We were always listening to new things from

overseas, always experimenting, trying to work out how they got

a certain sound or effect, and then try to reproduce it. I used

to listen particularly the English groups -- I felt they had

a bit more 'heart' than some of the American things, which could

be a bit 'flowery', as it were.

I personally supervised the entire installation

of the four-track and the desk at Festival when we moved to the

new premises [in mid 1967]. I was there day and night, every

day for about two weeks. Once it was in, I said to the chief

technician, the fellow who'd designed it all "Well, nobody

else knows this like I do" -- which was perfectly true --

"so I'm going to do all the engineering". And they

said "OK".

I did all my own engineering. The 'flanging'

on Guy Fawkes I did myself.. I held my finger on the rim

of the tape reel to control the effect -- that was all done in

one go. We didn't have a lot of equipment, like compressors and

things like that. The only major thing we used was the Pultec*,

but that was great, it really gave the sound a lot of 'bite'.

[*Pultec was a brand of audio

equaliser made by Pulse Technololgy P/L of New Jersey. They were

a staple of many top studios in the '60s (e.g. Motown) and are

now a highly prized piece of vintage studio gear.]

Of course this was in the days before things

like fuzz boxes. Do you know how we got fuzz tone on the guitars

back then? We used to go down to Allens music store from time

to time, and we'd a few second hand Fender amps, little ones

that had been traded in for bigger models. We'd take them back

to the studio and take a razor blade to the speaker cones. It

would give you a wonderful distorted sound. We used to have great

fun with that!

I remember it being a very happy working relationship.

We worked very, very hard but we got results and we had a lot

of fun. It was a fabulous time.

The debut DMS single, released in October

1967, was Why Why Why, a cover of a Paul Revere

& The Raiders song, written by their bass player Philip Volk.

The B-side, Hard Hard Year was actually the first DMS recording,

and was cut some time before the A-side. It was produced by Robert

Iredale, who worked on many famous early recordings for Festival

including The Bee Gees, Col Joye, Johnny O'Keefe and Dig Richards

& the R'Jays.

According to Dave, Hard Hard Year

was primarily a test to see how well they worked in the studio.

Spin were obviously happy with the result, so Nat Kipner teamed

them up with producer Pat Aulton, who had just become Festival's

house producer, for the recording of what became the A-side. At

Pat's suggestion they flattened the song out from 3/4 to 4/4,

because Hard Hard Year was in 3/4 time. Dave's delivery

showed a definite Eric Burdon influence, but it's a very creditable

effort.

The single had only limited exposure

in NSW, but remarkably, it charted in NZ when they toured there

at the end of 1967, thanks to support from pioneering Auckland

pirate radio station Radio Hauraki. It was also anthologised

on the 1968 Spin various artists compilation So Good Together

... The Stars of Spin.

To get back to New Zealand, Dave had

taken a typically ingenious step -- he approached the P&O

cruise line and worked out a deal to to provide 10 hours of entertainment

per week in return for passage to New Zealand and back on the

liner Himalaya during one of its Pacific cruises. It was

a roaring success, as Dave recalls, and the cruises became an

annual fixture:

It was one of the happiest boats I've ever

been on, one of the most absolutely ecsatatic, fun times of my

life, and the band's life. And the very first night we started

playing at 8 o'clock and we were still playing at eight the next

morning. We'd honoured our commitment in one night!

With typical aplomb, Dave also arranged

a special party performance for the crew, and this too was a great

success. The staff decorated the mess room specially and togged

up in fancy dress for the occasion. It paid off handsomely in

goodwill between the band and the crew -- as Dave's says, "I

never even had to lift a guitar pick after that!"

The success of the record was gratifying,

but the trip to New Zealand had another vital outcome. They were

low on cash and had been struggling with woefully inadequate equipment,

so Dave tackled the problem with his usual creative flair:

When John brought Bob Thompson into the band

he had a horrible little el-cheapo bass guitar, and virtually

no equipment, and I was running around trying to provide him

with bits and pieces. It really was difficult, and the band was

desperately short of equipment, and on that first trip back to

New Zealand, I could see the desperation that I was going to

be faced with. So I went to company in Auckland that Brian Ringrose

and I had dealt with quite a lot, called Jansen. They were an instrument manufacturing company, they

made amplifiers, all sorts of electronic accoutrements, and they

also made a range of electric guitars and basses and acoustic

guitars ... in terms of New Zealand I suppose they were the equivalent

of the Fender factory, they covered the whole gamut. I knew these

people from the days of The Byrds of course. We'd moved into

Jansen equipment and we used to promote that on stage. So in

desperation I went to the factory and spoke to the people, cos

they remembered me of course, and said "Can you do us deal?"

And they did us a deal for a range of photographs, etc, by which

we bought the stuff at cost. But that also posed me huge headache,

because we didn't have too much money ... the truth is I borrowed

the money from my father."

That put us really on the rails, because

Bob had a Telecaster-type bass copy, a 150 watt amp with four

cabinets with two twelves in each. John had two cabinets with

four twelves in each, and I think he had a 100-watt head. So, all of a sudden we'd gone

from being 'Mickey Mouse' in terms of equipment, to being a very

professional band. We were quite the envy of many contemporaries

of ours when we got back, for the very simple reason we went

away being rather pathetic and puny, and we came back looking

thoroughly professional. There were a lot of people really not

sure how and why all this had come about, but that really did

help, because we needed that equipment.

Acquiring the new gear was timely --

by '68 the influence of Cream, Hendrix and The Who were reverberating

around the world and the combination of their own keen ears and

the powerful new gear sound enabled DMS to become the first local

groups to pick up on this trend and develop it convincingly in

the local context. When the group returned to Sydney in early

1968 they scored a residency at the Op-Pop disco in Sydney, where

they shared a bill with The Twilights -- "definitely a class

act" recalls John -- one of many top Aussie acts with whom

the DMS regularly shared the bill, including The Masters Apprentices,

Tamam Shud, Doug Parkinson and Jeff St John.

Their next single, appropriately entitled

Hope, had a particularly interesting background. The original

version came from the 1967 debut album by The Candymen, and it

was co-written by Buddy

Buie and Candymen lead guitarist John Rainey Adams. They started out in the '50s in Dothan, Alabama

as members of The Webs, the group that launched the career of

singer Bobby Goldsboro, a childhood friend of Buie's. When they

backed Roy Orbison on a visist to Dothan he was so impressed that

he hired them on the spot as his permanent band, and and Buie

became his tour manager. Renamed The Candymen, they worked with

Roy for seven years, touring the world, and Adkins played lead

on many 'Big O' classics including Oh Pretty Woman. After they left Roy they cut two albums under their own name for ABC and Buie became a successful songwriter-producer, with credits including the Classics Four's Windy and Spooky, as well as hits for Billy Joe Royal and BJ Thomas. In the '70s he set up his own studio in Atlanta, where he put together the

session band that became The Atlanta Rhythm Section.

Released in April 1968, Hope was

a quantum leap in the band's studio work. Dave cites it as one

of his favourite recordings, and its not hard to see why -- it's

a psych-pop classic, a tremendously strong and hugely enjoyable

record that brims with confidence and optimism. Dave's vocal is

spot-on and the infectious backing, in a brisk march tempo, skips

along with some great ensemble playing by the group. It's topped

off by Pat's sparkling arrangement for horns, piccolos and strings

(with contributions from Sven Libaek, who scored the horns

and piccolos). The B-side is a swinging, good-time version of

Sam Cooke's Havin' A Party, a perennial stage favourite

that Dave often performed with The Byrds which he updated with

the namechecks of Stone Free and Strange Brew. The

single did quite well in Sydney, peaking at #27, largely thanks

to Ward Austin of 2UW who liked the song and was instrumental

in breaking it into the chart with regular airings on his afternoon

shift.

In another example of Dave's inventive

entrepreneurial skills, the group signed a promotional deal with

the AMCO jeans company, which paid off in many ways -- not least

in the form of free clothes! They made appearances providing music

for Amco promotions in shopping centres and other venues, and

this brought them into contact with 2UW's Ward "Pally"

Austin, Sydney's leading pop DJ, who MC-ed the shows. Ward

loved Hope, picked it up immediately, helped it become

a Top 10 hit in Sydney, and became a long-term supporter.

The powerful Jansen gear gave them an edge over most other

Sydney groups, and their act was now starting to included longer

songs, extended solos from John, and improvised jams. Their gigging

range also expanding to include Newcastle and Wollongong, and

they soon developed a very strong following in both those cities.

By the middle of the year Hope had been picked up by 2UW

and was in the charts and DMS came in at No. 7 in the Go-Set

National popularity poll. As John observes: "Not bad for

a band that had not yet visited that Holy Grail of Oz Rock, Melbourne."

Later in 1968 Hope was also included on the Calendar compilaton

Australia's Star Showcase '68.

Late in the year there was another important

musical development, thanks to Dave's keen ear and his industry

connections:

John: Dave brought

along a pre-release copy of Led Zeppelin 1 to rehearsals

one day, and we proceeded to cover every viable tune on it. By

the time it was released here, we had been performing most of

it on stage for over five months! This added to our credibility

to no end with the punters.

The third single, released in October

1968 was a truly superb cover of The Youngbloods' peace-and-love

anthem Get Together , a song was recommended to Dave by

Pat Aulton. It should not be confused with Let's Get Together,

the saccharine Hayley Mills hit from 1961, a mistake that is often

made in references to the DMS. Their version of Get

Together is a real gem -- miles stronger than the original,

which sounds rather anaemic by comparison. (It's a great pity

that the DMS version was not used in favour of the original on

the soundtrack of the hit Australian movie The Dish.) Pat

Aulton's producton is typically brilliant, dynamic and beautifully

balanced; the rather fey and folky style of the original has been

transformed into driving 'west-coast' psych-pop and given some

classic '60s spice by the addition of John's newly-acquired and

highly-prized sitar, "a beautiful instrument" Dave remembers,

specially made for John by a leading firm in India.

The b-side Bread and Butter

Day is a driving slice of heavy-soul which gives a clearer

hint of what the band were delivering live. It was also an important

advance for the group -- Dave's first original song to be commerically

released, and John's first opportunity to really stretch out as a lead guitarist on record. He spikes the track with some scorching licks, climaxing

in a wailing, Hendrix-like solo. Lyrically, it convincingly explores

the "life is tough" theme, similar to that of Hard

Hard Year and for any working muso of the time, the phrase

"bread and butter day" was certainly an apt description

for their often hand-to-mouth existence.

After another round of local touring to promote the new single,

there was a second Pacific cruise at the end of 1968, which again

had important outcomes. In Wellington, John Robinson went to the

movies and caught Sergio Leone's spaghetti western For A Few

Dollars More. He had developed a keen interest in film music

after seeing Kubrick's SPARTACUS when he

was young, and he was captivated by the Ennio Morricone's classic

soundtrack. Because there was no soundtrack available John went

to see the film over and over to memorise the music; soon he was

lobbying the band to include some of his Morricone-inspired instrumentals

into the set list, and these were well-received by audiences.

They also went to Fiji with the cruise, and while in Suva they

picked up Jeff Beck's Truth album, which Dave cites

as another big influence on their repertoire. A remarkable outcome

of the visit was that Get Together became a local hit in

Fiji. Dave has flippantly suggested that this might have been

due to the fact the arrangement featured John's sitar, which (pardon

the pun) struck a chord with the locals, many of whom were of

Indian descent. But in a seroius tone but he does say that the

crucial factor was that a new civic auditorium had just been opened

in Suva. The DMS were the first non-Fijian group to play there,

performing a sold-out matinee that was packed into the aisles.

It was followed by a well-received nightclub gig that evening.

This made a very favourable inpression on the Suvans and firmly

established the DMS name there, and certainly they would have

heard few bands like them in previous years.

By the time of the Xmas '68-69 cruise, Bob Thompson was homesick

and keen to return to the UK. John convinced him to stay until

the cruise was over, afte which Bob departed in March 1969. (Much

to Dave's chagrin, he sold his Jansen bass rig to pay for his

ticket home). He was replaced by bassist Leith Corbett,

who had just left Sydney club band Heart'n'Soul.

Leith was already a friend, since the two groups were both handled

by the Nova

booking agency and often played the same venues, like the popular

Here Disco in North Sydney. Leith was actually not Dave's

first choice -- he originally approached Mecca bassist Bob

Daisley, who later joined Kahvas Jute.

But Leith's fluid bass style was right in line with their new

direction, and his flamboyant stage presence and flying mane of

hair also added signficantly to the group's stage presence.

By the start of 1969 the Set had become one of the most popular

live draws in the Sydney-Newcastle-Wollongong region, and each

new single had gained successively greater attention. Yet throughout

their career Melbourne was more or less a "closed shop"

for them, and despite several visits there they were unable to

crack the scene. They made a number of visits there after Hope

came out, playing venues like Berties and Sebastians, and even

appearing on UPTIGHT, but although they were well received in

concert they never manage to overcome industry resistance, especially

in radio -- Stan "The Man" Rofe was the only Melbourne

DJ who supported them and played their records, according to Dave.

In late January 1969 the DMS joined 9 other top bands at the

annual Moomba concert at the Myer Music Bowl, headlined that year

by the Masters Apprentices. The huge crowd, estimated at well

over 100,000, was second only to the crowd record of 200,000 set

by The Seekers at the 1967 Moomba concert. By all accounts it

was a wild event -- fifty people were injured, including three

police, "countless" others had to be treated for hysteria,

and twelve were arrested after fights broke out in various sections

of the crowd. During the DMS set a group of youths climbed the

cables onto the roof of the Bowl and started pelting police and

the crowd with bottles and other objects and concert promoters

Amco and 3UZ eventually had to stop the show for half an hour

while police regained control. At another point mounted police

were called in to disperse a group of about 400 brawling youths.

A contemporary newpaper about the show can be seen on page 168

of Jim Keays' book His Masters Voice, including a photo

of the Masters onstage, incorrectly captioned as being The Dave

Miller Set.

The band worked relentlessly but on the recording side, there

was a long gap -- almost a year -- between Get Together

and their next (and best) single. In early '69, around the time

that Leith joined, a friend at Polydor Records (David Kent, best

remembered of "Kent Report" pop charts fame) loaned Dave an advance copy of Sunrise, the debut album by Eire Apparent. Formed in Ireland, the band included guitarist Henry McCullough (later of Wings). Their album was produced and featured guitar contributions by Jimi Hendrix, whom the band had supported on tour in America in 1968. Dave was immediately captivated by two songs from the LP, Mr Guy Fawkes, written by lead guitarist Mick Cox (to whom Hendrix had given his famous hand-painted Gibson Flying V guitar) and Someone Is

Sure To, by lead singer Ernie Graham. Mr Guy Fawkes immediately inspired him and

he set to work remodelling the song to suit the DMS and convincing

the rest of the band and Pat Aulton that this had to be

the next single. Using his mother-in-law's reel-to-reel tape recorder,

Dave taped the song and then did a primitive editing job, literally

cutting the tape with scissors and splicing it with cellotape!

He cut it down from its original seven minutes length to something

around 3 minutes and over the next few months Dave and Leith worked

closely together on the arrangement and eventually they were able

to realise their plans thanks to Pat Aulton.

The result was a tour de force and its enduring quality

is a tribute to both band and producer. There are similarities

between Mr Guy Fawkes and The Real Thing, which

came out around the same time, but each evolved totally separately,

and Dave's clear, cinematic conception for his record shines through.

John Robinson's strummed guitar intro is every bit as evocative

and recognisable as that of The Real Thing. Leith's restless

and lyrical bass lines, the framework of the arrangement, are

eloquent without being intrusive; Dave's eerie, filtered vocal

gives it the perfect sense of strangeness, and the whole package

is beautifully realised by Pat Aulton's superb production, with

rich phasing, sound effects, an evocative neo-classical string

arrangement by Pat, performed by members of the Sydney Symphony

Orchestra. The explosion (also part of the original) Dave located

after a extensive search in the sound effects library at the ABC.

There is a restraint, a coherence, and a filmic sense to the song

that is absent from The Real Thing, which pretty well throws

in everything including the kitchen sink, production-wise.

And like its predecessor, Guy Fawkes continued the great

tradition of Aussie bands covering obscure overseas tracks and

coming up with versions that far surpassed the originals.

The energy-packed B-side, Someone Is Sure To, is a treat.

It makes very interesting listening now, sounding remarkably like

the choppy "new wave soul" stylings of the The Jam --

only about 10 years earlier! The double-tracked-guitar line that

closes the song is another innovative feature that makes it a

real discovery.

Mr Guy Fawkes it is now counted alongside The Real

Thing as one of the classics of Australasian psychedelia,

but the ironic twist to the story is that we almost didn't get

to hear it:

Dave: The guy

that was running the Spin record company -- it was based in North

Sydney in those days -- was called Tom Miller. I liked Tom immensely,

but the day that the promotional copies of Guy Fawkes

came out he called me on the telephone and said, "Can you

get down to the office?". I said, "Yeah".

Got to the office ... and I was pasted.

I was berated for "the worst piece of trash that the

Spin record company has ever been involved with", "an

absolute disgrgace". And I was

told that if it hadn't been for the fact that they trusted Pat

with this particular project, had they heard it at any stage

prior to this, it would never have been released. It was

the fact that it had already been pressed that meant they had

to go through with it. And they didn't want to know it. I was

told in no uncertain terms that it was the worst record that

the Spin record company had ever been associated with!

Of course, the result vindicated Dave entirely -- within weeks

of its release in July it was a Top Ten hit in NSW and at year's

end, Ed Nimmervol named it Go-Set's "Single Of The Year"

for 1969, an accolade of which Dave is justly proud. It was also

included on the Calendar compilation Australia's Top Talent,

one of the first local pop LPs to be released in stereo. Things

were really starting to look up for the group and the success

of Mr Guy Fawkes opened many doors for them.

At the session that produced the backing tracks for the Guy

Fawkes single, the DMS (sans Dave) also cut another

recording that Pat Aulton was producing -- the single Year

of War by Sydney singer Frank Lewis, with its melody lifted

from the famous Barcarolle from Offenbach's Tales

of Hoffmann. It too became a Top Ten hit in Sydney around

the same time as Guy Fawkes, and this created a unique

chart achievement for Leith, whose former band Heart'n'Soul

were also enjoying a hit with Lazy Life, a track cut just

before Leith quit and joined the DMS:

Dave: Leith

was in the charts with three records at one time, and this is

not a known fact for most people. He was in the charts with Lazy

Life, he was in the charts with Guy Fawkes and he

was in the charts with Frank Lewis and Year of War, which

was the Dave Miller Set, with Frank singing.

Another remarkable but little-known episode in the DMS story

took place in mid-1969, and we are very grateful to Dave for sharing

his recollections of this hair-raising affair, which he has never

before spoken about publicly. Through the middle of 1969, Dave

and John had been heavily involved in promoting Mr Guy Fawkes,

particularly with a popular 2SM DJ of the time, Mad Mel.

Mel and 2SM were organising a large inner-city concert, "Mad

Mel's Giant Stir", staged in The Rocks, on the grassed area

under the southern approach to the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

A few weeks before the Stir, the group was booked to play a

tour of Indonesia. It was a triple bill headlined by the DMS with

singers Mike Furber and Nikki Bradley,

whom they backed. The DMS went to Indonesia on a ten-day visa,

to play seven venues, 3 in Jakarta, two in Bali and one in an

another location. On arrival there was no proper itinerary waiting;

the schedule, such as it was, was to come back and play the seventh

gig in Jakarta and then back to Australia.

The tour played the first three nights in Jakarta in roofed

stadiums (built by the Dutch) -- where they were billed as "Beatles

dari Australia"! These were very large stadiums -- Dave

reckons the halls had a capacity of about 50-60,000 people --

much larger than anything the DMS had played before, except outdoor

gigs in Australia, and even then several times larger than the

biggest of those. All of the first three shows were sold out,

and at each gig many more people outside turned away. The DMS

sound relied on powerful amplification but the promoters only

provded them with puny Fender amps to play a huge outdoor sports

arena and the band had to try and play without the amps even being

miked and fed into the PA! Dave and John John both have rueful

memories of the sound:

John: It was

something like mosquitos buzzing around in a large public toilet.

Dave: The equipment

was pretty awful, we were trying to fill a huge auditorium,

and it was practially impossible. It was in the days before PAs,

mixing consoles, all that sort of thing.

Despite the technical shortcomings, the Jakarta gigs were a

success, the musicians were treated royally, and parties were

held in their honour. But after the third gig things suddenly

went "extremely wrong". The trickle of information suddenly

dried up, questions were not being answered, but Dave eventually

managed to discover that the scheduled gigs outside Jakarta had

been cancelled. Dave later found out -- to his dismay -- that

the promoters had also telephoned Sydney and fed both the Nova

agency and Dave's wife in Sydney a story (presumably also given

to the local press) that Dave was seriously ill, had been hospitalised,

and was unable to leave.

The full story, as Dave gradually pieced it together, was that

they were pawns in a rather shady game. Tickets for all the venues

had been pre-sold well in advance, but for some reason the promoters

had neglected to book the venues outside Jakarta. Unfortunately,

by the time the DMS and friends arrived, a major inter-Asian sports

event was in full swing. Needless to say, Indonesia was the host

nation, and the venues that would have been used for the concerts

were now all occupied. Presumably to avoid paying refunds, the

organisers had evidently decided to fabricate the illness story,

and hold Dave and the band incommunicado in Jakarta until

the sports festival was over and the concerts could be held.

Dave believes that the problems could have been easily solved

by negotiation between the promoters, the Indonesian authorities

and the Australian embassy, but in the event the promoters opted

to hush the whole thing up. In another time and place, this would

have been a problem rather than a crisis. But this was Jakarta

in 1969, and there was good reason to be very apprehensive.

Dave: "The

problem that I had was that we had a ten-day visa that was running

out at a very, very rapid rate, and I knew that in a country

like Indonesia ... which was extremely miltary in 1969

... if we did not have a permit to be in that country we could

be in dire strife. I could not get proper answers, and I could

not get authorities to assist me in any way, so they fabricated

the thing that I was ill."

We were being kept there to accomodate them,

so that they could save face, but no-one had taken into account

the precarious situation that we were placed in. ... I was extremely

uncomfortable with the predicament we were in. I have to tell

you -- it wasn't easy, and it was extremely dangerous

for Ray Mulholland and myself ... "

Marshalling all his considerable negotiation skills, Dave did

what he could to extricate the group from the situation. Through

contacts he had made, he was able to get in touch with one a senior

Indonesian police officer -- who by luck was an amateur jazz musician

and an avid fan of Western popular music. The contacts who arranged

the meeting did so, says Dave, at the risk of their own lives.

In the middle of the night, Dave and Ray went to the officer's

home, and although there was a family dinner in progress at the

time, he generously came out and listened to Dave's story. The

officer was very sympathetic, expressing great embarrrassment

over what had happened. He immediately organised a motorcade and

the band was ferried straight to the Jakarta airport, onto a QANTAS

plane and home forthwith. There was a happy postscript, however

-- on the plane home, the DMS was spotted by two Australian musos

who were on the same flight. They invited the DMS up to first

class where a raging party was in progress -- it was Johnny O'Keefe

and his entourage on their way home from entertaining the troops

in Vietnam!

Dave: "It

was champagne flight back for us after that, which was a nice

footnote to something extremely tense, extremely difficult."

Dave shielded the rest of the band, who were mostly unaware

of the dramas, but it was an unnerving experience for him, and

one that he has only recently felt comfortable to speak of.

By the time they arrived back in Sydney there was good news

waiting -- Mr Guy Fawkes had reached the Top Ten. Their

first major return gig after the Indonesian debacle was Mad Mel's

Giant Stir in August 1969, with a host of top Australian acts,

as well as visiting US singer Ray Stevens:

Dave: The profound

memory I have of the event was performing Mr Guy Fawkes.

I've never forgotten this. When it came to the explosion segment,

there were two trains approaching the bridge -- one to the south,

one to the north -- and right at the time of the explosion, both

those trains went across the bridge and crossed in the middle,

and the cacophony was quite incredible. It all fitted

into the texture of what was happening at the time, and I can

remember the crowd simply stoood and cheered. You couldn't have

planned it better. It was quite a magical moment.

Shortly after the Stir, Ray Mulholland left the group and he

was replaced by Mike McCormack (ex-Sect). The hard-hitting

drummer completed the Set's transition to a fully fledged heavy-rock

outfit, and in this final phase Dave also began playing rhythm

guitar onstage to bolster the sound during John's solos.

Dave: Mike was

I think one of the best heavy drummers in the country, in a 'John

Bonham' sort of fashion. Ray, having come through the Shadows

era was very "wristy" and I actually loved that part

of Ray's playing. He was very, very fluent with his hands on

the top part of the kit. Mike on the other hand was very dynamic

on the bottom part of the kit. If we could have been an Allman

Brothers sort of band, I would have had them both! (laughs)

It's regrettable that this lineup never really had the chance

to prove its mettle outside the live arena, and liewise it's a

real shame that the DMS never had the chance to record a full

album with Pat. Dave reckons they reached their peak as a performing

unit in the latter half of 1969, which was also probably the busiest

period of their career. They played countless city and country

gigs, and thanks to Dave's friendship with Sydney TV producer/host

John Collins they made numerous appearances on Collins'

late night music-and-talk show on Channel 10. They also recorded

a performance segment for the ABC's new nightly music show, GTK,

although it's know whether the tapes of this appearance have survived.

John Robinson was by now gaining a considerable following for

his guitar work, and he was also beginning to compose. Indeed,

he recalls that many musical ideas that began life in jams and

improvisations with DMS later became parts of Blackfeather's material

-- Seasons Of Change was one such song, born during an

onstage jam between Leith and John at Coffs Harbour in 1969.

The DMS played a lot of university gigs, and as Dave points

out, the music included longer arangements, with a lot of jamming,

extended improvistion and guitar pyrotechnics, simply because

that was what those audiences demanded. Still, Dave says that,

like most other acts of the day, they were a somewhat "schizo"

band, in that they could also adapt to a more commercial format

when playing to younger audiences. They could and did perform

a wide range of material, as he recalls, but the progressive material

was really the core of their music by this time and the ting that

set them apart from most other bands in the country.

Dave: By that

stage we were well and truly ensconced in that the progressive/underground

direction of music we were taking. The band had expanded so much

beyind the concept of a three-minute record that our live performances

were up in the echelon of Zeppelin, Who, Cream, whatever type

of band that you like to nominate. I don't want to be likened

to any or all of them, but there was an attitude to music and

its thinking and its style at that stage, and we were at the

forefront of that. If you look through my scrapbook, you'll find

there were many complimentary things written about the Dave Miller

Set as being as good as or better than some of the biggest interntional

names of the time.

We used to do a very very good version onstage

of The Weight, but we had to choose our material very

carefully, and we couldn't choose over-orchestrated stuff --

in the final analysis, we were just guitar bass and drums. It

was one of the reasons why I started to filter in on rhythm guitar,

to give John the space to become the "legendary lead guitarist"

and anchor the rhythm section a bit more.

Dave also recalled some of the hazards of life on the road

in the late '60s and gives a revealing insight into the reason

behind some of those long jams!

Dave: We travelled

a tremendous amount. We worked a lot. We did the country

gigs, we did the industrial centres, and we were constantly out

of Sydney as well as being in Sydney. When we were on the road

-- we lived in a time before mobile phones -- I was doing all

the bookings for us. We did have an agency; we worked thrugh

the Nova agency. I used them as a telephone answering system

for the most part. I couldn't be contacted because I was on the

road so extensively. But being on the road, I kept a schedule

of gigs and I created all the re-bookings in these places on

a cycle basis. I did the agency work and

in some places where I was encountering people for the very first

time, in fairly out-of-the-way places, I learned very quickly

there were "characters". I had heard from other people,

and I could see that this could unfold for me if I didn't keep

control over it.

A lot of people would use a powerful name,

get the country folk in from a large surrounding disctrict, and

the person repsonsible for operating this 'one night stand' would

often do a moonlight flit around 11:30 or so, in the half-hour

before the band finished. You'd come to the end of the night

and no-one was around with any money to pay anybody, and many

bands got ripped off by this absolutely uncouth way of doing

business. Nice as pie to your face at the beginning of the night,

but gone with the proceeds by the end. And of course everybody

that was left in charge of the place was told that the agencies

would be 'accomodated' in due course, and that's how it would

be.

When you're on the road, of course, you need

readies. And I found that I had to adopt a 'Chuck Berry' stance

with fly-by-nights like that. What I would do, knowing that there

were lots of people outside the venue, was that we would set

up and do a soundcheck, ostensibly -- and we would play BLOODY

LOUD so that everybody from around the township would know damned

well we were there. We'd do that and then shut down. Then I would

discreetly go to the namangement, go to the office and say to

them straight up: "Money NOW or we don't play." It

was that simple -- money up front, or we didn't play.

That's how I survived, but there were often

difficult situations and things that were rather untoward, and

there'd be many occasions where I'd just have to say to the guys

onstage: 'Play it out - I've gotta sort something out.' And I

used to have to -- as their manager, as their agent -- disappear

from the stage often -- and thus some of the protracted jams.

It was not me tiring of the thing, it was no me tiring of being

an artist. It was the fact that circumstances often made it that

I actually had to do some these things to keep on top of it for

the sanctity and well-being of the band. Thus