Booze was my life. I was a nervous wreck.

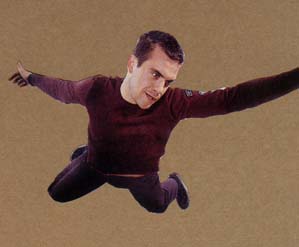

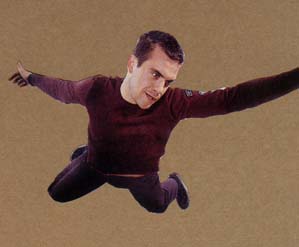

He was a teen star, then a fat joke - an infamous indie scene inebriate with a pop

career in pieces. Yet, suddenly, Robbie Williams is

seducing mature record buyers, brandishing platinum albums and having something

like the ultimate guffaw.

David Cavangh wonders, How did he do that?

"Basically, I'll tell you what happened. When I was in Take That, I used to work my bollocks off.

And the if we get a night off, I'd go out and get cunted. Yeah? As you do. so it all gets on top

and I leave the band. Now, once you've got no work, my instant thing is, go get pissed.

So I got pissed - for a year. Longer. Maybe a year and a half, two years. And when the time comes

for me to do work again, I'd completely forgotten how to stop drinking. As choreography had been a

part of my life, booze was a part of my life. I looked ridiculous. I was saying

rediculous things. And basically I'd got the potential to be one of the biggest artists in the world

if I put the work in, look fine and say good things."

"Basically, I'll tell you what happened. When I was in Take That, I used to work my bollocks off.

And the if we get a night off, I'd go out and get cunted. Yeah? As you do. so it all gets on top

and I leave the band. Now, once you've got no work, my instant thing is, go get pissed.

So I got pissed - for a year. Longer. Maybe a year and a half, two years. And when the time comes

for me to do work again, I'd completely forgotten how to stop drinking. As choreography had been a

part of my life, booze was a part of my life. I looked ridiculous. I was saying

rediculous things. And basically I'd got the potential to be one of the biggest artists in the world

if I put the work in, look fine and say good things."

Whiplashing his tenses like a dodgem slamming against a rubber circumference, Robbie Williams is ever so

keen to self-appraise. He can breeze through five years in as many seconds. Take That? Ner ner, Gary

Barlow, rashin-fashin Dick Dastardly, ner ner, booze, drugs, rehab. You can tell Robbie

comes from a showbiz background: when he starts to sing a song, he ends up singing the whole song,

practically getting down on one knee like Al Jolson.

In his life as one fifth of Britain's biggest-selling boy band, Robbie was on sale in the shops as a

duvet-cover, a doll and a pillowcase: a Stoke-on-Trent teenager playing shelf wars with Snoopy and Tiny

Tears. He arrived in a box and left in a bag. As if by afterthought, the group also made records.

Robbie hadn't a clue who produced them, let alone played on them, and couldn't have pointed out the

studio where they were made if you'd shown him a photograph of it.

"The most embarrassing thing I've ever had to endure in my life was on a schools tour of America with

Take That," he says with emotion. "It was at the height of the New Kids On The Block backlash and very

'street', and we had to sing a song called I Found Heaven. I was dancing almost apologetically."

In 1996 he started making records under his own name. Ousted controversially by Take That, he put out

a symbolic cover version of George Michael's Freedom '90 I Will Survive or

If My Friends Could See Me Now - and sold a creditable 270,000 copies. He followed this with three

deliberately raucous, Oasis-style singles in 1997, outlining more and more of his new direction and selling

progressively fewer and fewer records. The fourth of these singles, South Of The Border, saw his fanbase

slump to a dismaying 40,000 in September.

BY THE end of November, Robbie was haemorrhaging fans left, right and centre. His album, Life Thru A Lens,

totted up a catastrophic take-home of 33,000 copies in its first eight weeks, before disappearing from the chart

altogether. The three-album deal he had signed with Chrysalis on the sroke of 00:00:01 a.m. on June 27, 1996

was starting to liik increasingly extravagant and over-optimistic. As a last resort,

the ballad Angels was released by Chrysalis as a single on December 1, 1997.

Angels was to rescue Robbie's career at a stroke. It's stirring nine-note stairway arpeggio lift-off

("and through it all...")proved enough of an Elton John-like hook to entice those winter buyers craving a

fix of something not too disimilar to Candle In The Wind, while its arrangement offered sufficient

drama to place Angels in the respectable company of top-drawer weepies like Eric Carmen's All By

Myself, The Hoolies' The Air The I Breathe and Kiki Dee's Amoureuse. In short, the mums

bought it and, two months after release, Angels was still in the Top 10.

This left Robbie in an interesting position. He hardly needed the money. He certainly didn't need fame.

He only needs (as he says) to walk down the street for the car-horns to start beeping at him. What Angels

has giving him is something he's never had before: a potentially long and artisically prosperous life in music.

For all The Verve's trophies, Robbie is the first commercial pop phenomenon of 1998.

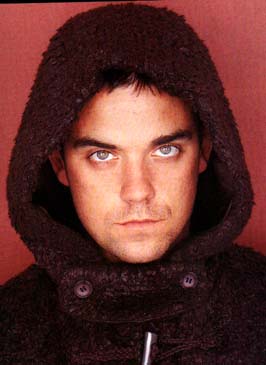

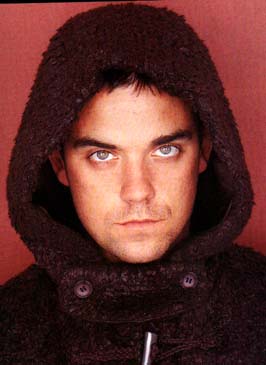

It is approximately 1.15 on a golden Tower Bridge afternoon. Bronzed from two weeks in Jamaica, Robbie

has flown back to London to face the happy music. In a studio just south of the Thames, he tells a good story

about dropping in on Sly & Robbie in a Kingston studio and being completely ignored. He makes eye contact

very early, and smokes cigarettes like a snooker player watching Stephen Hendry compile his seventh successive

maximum break.

Q isn't immediately sure how seriously it should take Robbie. Two months ago he was pop history. Now he's a good

bet for the Music Week's Man Of The Year. "The Brook Green team (Chrysalis) got their reward over the

festive season," fawned the trade paper's editorial on January 17. "The once-wayward Robbie

has blossomed into a real star."

Oh, he has? Angels was written a year ago, and those who reviewed the album in September

either ignored it or picked it as the worst song. Suddenly we all knew he had it in him?

In two interviews to promote the album, Robbie said that he didn't care how well it sold; that

pop music was just a hobby; and that if it all went belly-up tomorrow, he could always become an actor.

No mention of Angels there.

Oh, he has? Angels was written a year ago, and those who reviewed the album in September

either ignored it or picked it as the worst song. Suddenly we all knew he had it in him?

In two interviews to promote the album, Robbie said that he didn't care how well it sold; that

pop music was just a hobby; and that if it all went belly-up tomorrow, he could always become an actor.

No mention of Angels there.

"Protection," he explains hastily. "I didn't know how the album was going to be received, and I was probably

covering myself. Put it this way, I don't want to do anything else but make music."

If we're going to salute Robbie, and there's something very likeable about him

that makes Q want to try, let's do so for the right reason. Not because he left a boy band in order to become an alcoholic.

Not because he climbed calculatingly on board an Oasis bandwagon, even modifying his singing style on certain songs to

accommodate tell-tale inflections of Liam Gallagher. And not because he made an album pissed, either.

Here are the reasons why Robbie deserves acclaim. He is an old-fashioned entertainer, raised on Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan

and Tom Jones, who brings showmanship, humour and versatillty to a down-at-heel indie-rock circuit. He has, from a standing start,

already shown evidence of a sparkling talent for putting words together: like early Rod Steward with hints of Morrissey

and Shaun Ryder. Angels is very good. Baby Girl Window, the album's final song, is even better.

And rather than just make another album like Life Thru A Lens this year, he wants to get into new recipes of hip hop, guitars

and stream-of-consciousness wordplay. A song he recorded last night, which he playeds on a ghetto blaster, is more novel than anything

on Life Thru A Lens: syncopated with clavinet, funk guitar and a New Orleans flavour - Beck meets Dr John meets the sound of

Robbie Williams pushing himself.

"I have ridiculously eclectic tastes," he reveals. "The first album I bought was The Wall, I grew up listening to

Showaddywaddy, Adam & The Ants, Darts and loads fo electro stuff - Doug E. Fresh & The Get Fresh Crew, Afrika Bambaataa,

Grandmaster Melle Mel & The Furious Five. At school I listened to hip hop. But I aspire

to Las Vegas. Fifteen years from now, I just want to be able to sing Angels and say, This song has been very

good to me. Tom Jones is a definite hero."

If you listen to every song Robbie has released as a solo arist (and there are more than you might think: 23 of them), he

covers a variety of styles - from standards (Ev'ry Time We Say Goodbye) to Pet Shop Boys-style Euro-ennui (Falling In Bed Again); from

mincing cover versions (Kooks) to poignant acoustic reveries (Baby Girl Window).

It transpires that he once tried to persuade Take That to do a live versio of Primal Scream's Rock.

He even got them to listen to the song. ("I think somebody said it was too clever," he recalls.)

"What do I know about rock'n'roll? I wouldn't have an A-Level, but I'd have a GCSE. I've been watching VH1 Rock Legends a lot

recently, to tune up on my knowledge," he smirks. "When I met Oasis, I was already a big

Beatles fan. But we were very closted in Take That. We weren't allowed to talk to people,

or find out anything about ourselves. I'd already gone a before. I'd said to the boys, After this tour I want to leave.

And everybody cried. I said, All right, I'll stay. Then I went to Glastonbury and I thought, Fucking hell,

Liam gets to do all that? Can I get the sack now?"

Robbie's solo career began with a pointed dig at his former band. It continued with a meaningful

(to him, if no-one else) cover version of XTC's Making Plans For Nigel on an early

B-side. He then told journalists he was working on a song to fix Gary Barlow's wagon good

and proper, to be called Ego A Go Go (eventually written in early '97, it appears

on his album). And, sure anough, he was still stirring things on his tour last autumn, ending the show each night

with a frenetic punk annihilation of Gary's beloved Back For Good. He even bought Gary's solo album

in HMV last June just so he could return it the next day, loudly demanding his money back.

All good fun, of course, if of little value to the consumer. What really pisses Gary off, surely, more than any of this,

is the cruellest truth of all: that Gary didn't write Angels himself.

"Of course," Robbie nods, in a glad-you-spotted-that sort of way. "But he coulnd't write Angels.

He couldn't write a song with such spiritual intent and actually mean it. I don't mean that in a disrespectful

manner. I saw him a few months ago and we laid a few things to rest. But he couldn't write that. He couldn't

write that."

In fact, Angels was a co-write between Robbie and his increasingly valuable musical director,

keyboard player and producer, Guy Chambers. An ex-member of World Party and songwriter in an early '90s band called

The Lemon Trees, Chambers is Robbie's fith songwriting collaborator in 18 months. It is he who made the

difference: he brought the Beatles-Oasis sensibility that Robbie wanted - along with an old Lemon Tree song called

Lazy Days, which became, with rewritten lyric's, Robbie's third single - and Chambers will have the job

of producing and co-writing the next album.

Chambers came from a list of names to Robbie by Chrysalis at the beginning of 1997. By that time, Robbie

had been through four co-writers in 18 months and had a grand total of two usable songs. The first of these,

written in the summer of 1996, was Cheap Love Song, a My Sweet Lord-style mid-pacer

(and B-side of South Of The Border) that emerged from a shorlived songwriting spree with Owen Morris,

producer of Oasis and Ash. When Robbie fell out with his then manager, Morris's friend Tim Abbot, the majority

of the songs were scrapped.

His next writing partner was Anthony Genn, who had played bass in a mid-80's line-up

of Pulp, but was more famous as the streaker who ran on to the stage during Elastica's performance at

Glastonbury in 1995. As the festival's other news-making stage-invader that year (with Oasis), Robbie was

understandably drawn to Genn. However, none of the seven songs they wrote in tandem has been released, or looks

likely to be.

His next writing partner was Anthony Genn, who had played bass in a mid-80's line-up

of Pulp, but was more famous as the streaker who ran on to the stage during Elastica's performance at

Glastonbury in 1995. As the festival's other news-making stage-invader that year (with Oasis), Robbie was

understandably drawn to Genn. However, none of the seven songs they wrote in tandem has been released, or looks

likely to be.

Towards the end of 1996, having come up with not one tune that could legitimately follow up

Freedom '96 as a single, Robbie took the advice of his record company and flew to Miami to

write with Desmond Child and Eric Bazilian, and record with American session musicians.

Child was near-legendary: he had written for Bon Jovi and Aerosmith. Bazilian, as Robbie

was often reminded, had written One Of Us for Joan Osborne. These were unusual (and expensive)

collaborators for someone looking to have himself a mouthy Britpop smash his, and Robbie admits

he found the experience far from liberating.

"Desmond Child is a funny man," he says, shaking his head. "I don't mean to be disrespectful,

but... Do you like my swimming pool, Robbie? You should do, you paid for it. They're nice people,

but in their own sort of Bon Jovi-esque manner. I left the studio one night and I said,

Listen, this song has not got that British, ironic feel to it. So I came in the next day and I could

tell Desmond had been awake furiously thinking about this. He says, I've had this great idea. It's

called The Boys In The Pub..."

Somehow, as a trio of men might build a conservatory, they constructed Robbie's second solo single,

a song called Old Before I Die.

"Bazilian was the main driving force behind Old Before I Die, and when I got home I thought,

This is a good tune, it's sort of pseudo-indie, but that's fine. I phoned Bazilian up and he said that

Desmond really helped a lot and, you know, the three of us should write together...No good."

Robbie candidly describes himself as a nervous wreck throughout this period, but he at least had the

confidence, on his return to England, to dump the Miami recording of Old Before I Die

and begin again, and not to even bother with four other Child-Bazilian songs.

"I talked myself out of five very big American radio hits," he says philosophically. "But I might

as well still be in Take That if I'd sung those songs."

Finally, for no other reason than the fact that his mother's boyfriend had quite liked

The Lemon Trees, Robbie chose Guy Chambers. They wrote Angels together within hours

of meeting.

AFTER THIS comedy of errors, timewasters and compromises, Robbie probably deserves

to savour his last laugh. The irony is that he has only fleeting memories of making the album.

Immediately after completing it, he was in rehab.

AFTER THIS comedy of errors, timewasters and compromises, Robbie probably deserves

to savour his last laugh. The irony is that he has only fleeting memories of making the album.

Immediately after completing it, he was in rehab.

The saddest thing he says all day relates to a time in his life when he doubted he even had

a future as a performer. It was only seven months ago. Not long out of the clinic, still feeling

frail, he was due to shoot a video for his projected fourth single, Let Me Entertain You,

one of the album's mor abrasive tracks. Two days before the shoot, he telephoned his management

to cancel the release.

"I couldn't have put out a song that asked that," he explains. "I couldn't have asked the public,

Let Me Entertain You. I hadn't got the confidence. Because somebody might have said, No."

Mark the differnce in the 24-year-old now, though. He is the biggest selling ex-Take That member, out-performing

Gary Barlow, and his album has one more single to come. A few months late, Let Me Entertain You

is scheduled for March 16. He is now able to ask that of the public.

And he's thought of something funny. "I was round Noel's house one day in 1996,"

he remembers, "and he'd got this great song. It was called Freedom, funnily enough.

He goes, It's for you if you want it. But it's five o'clock in the morning," he ruefully smiles,

"and of course I completely forgot all about it."

Q Magazine, April 1998

HOME

"Basically, I'll tell you what happened. When I was in Take That, I used to work my bollocks off.

And the if we get a night off, I'd go out and get cunted. Yeah? As you do. so it all gets on top

and I leave the band. Now, once you've got no work, my instant thing is, go get pissed.

So I got pissed - for a year. Longer. Maybe a year and a half, two years. And when the time comes

for me to do work again, I'd completely forgotten how to stop drinking. As choreography had been a

part of my life, booze was a part of my life. I looked ridiculous. I was saying

rediculous things. And basically I'd got the potential to be one of the biggest artists in the world

if I put the work in, look fine and say good things."

"Basically, I'll tell you what happened. When I was in Take That, I used to work my bollocks off.

And the if we get a night off, I'd go out and get cunted. Yeah? As you do. so it all gets on top

and I leave the band. Now, once you've got no work, my instant thing is, go get pissed.

So I got pissed - for a year. Longer. Maybe a year and a half, two years. And when the time comes

for me to do work again, I'd completely forgotten how to stop drinking. As choreography had been a

part of my life, booze was a part of my life. I looked ridiculous. I was saying

rediculous things. And basically I'd got the potential to be one of the biggest artists in the world

if I put the work in, look fine and say good things." Oh, he has? Angels was written a year ago, and those who reviewed the album in September

either ignored it or picked it as the worst song. Suddenly we all knew he had it in him?

In two interviews to promote the album, Robbie said that he didn't care how well it sold; that

pop music was just a hobby; and that if it all went belly-up tomorrow, he could always become an actor.

No mention of Angels there.

Oh, he has? Angels was written a year ago, and those who reviewed the album in September

either ignored it or picked it as the worst song. Suddenly we all knew he had it in him?

In two interviews to promote the album, Robbie said that he didn't care how well it sold; that

pop music was just a hobby; and that if it all went belly-up tomorrow, he could always become an actor.

No mention of Angels there. His next writing partner was Anthony Genn, who had played bass in a mid-80's line-up

of Pulp, but was more famous as the streaker who ran on to the stage during Elastica's performance at

Glastonbury in 1995. As the festival's other news-making stage-invader that year (with Oasis), Robbie was

understandably drawn to Genn. However, none of the seven songs they wrote in tandem has been released, or looks

likely to be.

His next writing partner was Anthony Genn, who had played bass in a mid-80's line-up

of Pulp, but was more famous as the streaker who ran on to the stage during Elastica's performance at

Glastonbury in 1995. As the festival's other news-making stage-invader that year (with Oasis), Robbie was

understandably drawn to Genn. However, none of the seven songs they wrote in tandem has been released, or looks

likely to be. AFTER THIS comedy of errors, timewasters and compromises, Robbie probably deserves

to savour his last laugh. The irony is that he has only fleeting memories of making the album.

Immediately after completing it, he was in rehab.

AFTER THIS comedy of errors, timewasters and compromises, Robbie probably deserves

to savour his last laugh. The irony is that he has only fleeting memories of making the album.

Immediately after completing it, he was in rehab.