Patrick Cudmore passed away on 7 October 2001, of a heart attack. To quote a close friend of his - "Patrick was an amazingly unique individual and will be sadly missed by all who knew him."

The following article is from the January 1985 issue of

"Sail" (ISSN 0036 2700), page 89, and was part of a special section titled

"Introducing Tomorrow", concerning technological developments in sailing.

Both the text and photographs are by Keith Taylor, the magazine's then editor, and are ©

"Sail" magazine.

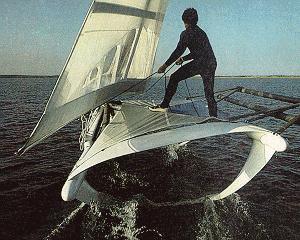

At rest on the wind-roiled waters of Duxbury Bay near Plymouth, Massachusetts, "Seaflier" looks for all the world like a big wounded seabird. Low in the water, its single wingsail cocked at an awkward angle, and the tops of its pontoons lapped and splashed by water, it seems to be losing the battle to stay afloat. Adjustments completed, its solitary rider pivots the Dacron wing to its optimum angle of attack, and "Seaflier" takes flight powerfully and gracefully. Under ideal conditions and with adroit sheeting, it is foilborne, climbing up 2 feet vertically and reaching or exceeding windspeed in two or three boatlengths while unschooled spectators gasp in amazement.

Launched in October last year [1984], the current

prototype is the third in a series first conceived by its designer, Patrick Cudmore, in

1971. Cudmore's earlier work received recognition from a variety of sources,

including Boston's Museum of Science and the 1981 Rolex Spirit of Enterprise Awards

judges, but it took the involvement of Peter Wallace, an Australian entrepreneur

living in Boston, to make the latest boat a reality. Wallace and Cudmore, partners

in the Seaflight Corporation, now envisage production boats and a sport that will

leave boardsailing in their spray. Both men acknowledge, however, that they must

first develop and refine sailing and control techniques.

Neither hydrofoil sailboats nor canted rigs are particularly new, but Cudmore's

lightweight proa-configured craft with its cantilevered, articulating wingsall and

inverted, elliptical arch, surface-piercing foils offers a glimpse of a future made

possible by sophisticated design and strong but light composite plastics.

According to the inventor, his craft "operates at

three performance levels: in buoyant or displacement mode at speeds under 5 knots, in

hydrodynamic mode at intermediate speeds to 14 knots as the majority of lift develops on

the top surface of the foil, and in hydroplaning mode as the underside of the foil

achieves lift near the water's surface at high speed."

The mast canted to weather is intended to reduce heeling moment while generating vertical

lift as well as forward thrust. The sailor stands to sail the boat, grasping the two

lines that control the angle of the balanced wingsail. Because of the balanced

effect of the sail, sheet loads are minimal. "Tacking" is achieved by

bearing off onto a reach, feathering the sail, and then rotating it and reversing its

curvature before accelerating on the new tack.

In its present form "Seaflier" has no rudders. Steering control when

foilborne is achieved by rolling the craft sideways. Rolling to windward turns

the boat away from the wind. Rolling to leeward causes it to round up.

Although rudders were initially eliminated to minimize drag, it became obvious in early

sea trials that some form of low-speed steering control was necessary.

Once

up on the foils, the craft seems relatively stable in pitch, although optimal

performance is achieved in a fairly narrow range. Cudmore says it achieves its

best lift-drag ratio at a 2-degree angle of attack.

Achieving a consistent angle of attack and the required degree of roll is one of the

problems Wallace, Cudmore, builder Ted van Dusen, and technical assistant Scott Clifton

are still overcoming. In the boat's first weeks of testing in a variety of

conditions, a typical flight covered anywhere from 100 yards to 1/4 mile. The boat

climbed onto its foils in windspeeds of 8 to 10 knots and demonstrated considerable pitch

and roll stability in flat water and rough. Although weather problems, breakages,

modifications, and the cold water of Duxbury Bay conspired to limit sailing time, everyone

concerned with the project has successfully flown the boat.

[End of article.]

The Seaflier was an interesting project to work on. The foils worked quite well and lifted the boat out of the water quite gently. Translating Patrick Cudmore's concept into a functioning reality was sometimes a challenge. The cambering wing type of sail plan, for example, needed some more development work.

Patrick had hoped to control the direction the boat sailed by heeling the boat so the center of effort moving to weather or leeward would make the boat head up or down. The response was too slow to deal with gusty conditions. When flying, heeling the rig to leeward would slowly make the boat head up; however, when the leeward pontoon touched the water the drag turned the boat the other way. Trying to run in and out on the rack to control the heel and trim the sail to suit the wind direction required more skill than we could master in a few dozen trials. We tried adding a large rudder, but with all the foil area the response was sluggish and it was one more control to deal with. We did manage a few spectacular runs which showed good potential.

[End of addendum]

If you have further information on this craft, please email aerohydro.