|

Ghost on Grant Street?

Some say a dead federal judge still comes to work at the courthouse -- in spirit

Sunday, April 09, 2000

By Torsten Ove, Post-Gazette Staff Writer

He was a bearded, barrel-chested judge from Erie who smoked six cigars a day despite the occasional objection from someone in a courthouse elevator, and he didn't put up with much nonsense.

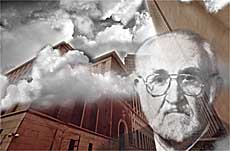

Does the ghost of U.S. District Judge Gerald J. Weber haunt the federal courthouse? (Peter Diana, Post-Gazette illustration)

When a defense lawyer once argued that his client deserved leniency on the grounds that he had learned his lesson, the judge said, "The only thing that's going to teach him a lesson is when he hears the cold steel bars of the jail cell closing around him."

Despite his pragmatism, U.S. District Judge Gerald R. Weber was smart as a whip, a Harvard graduate, a World War II intelligence officer and a man who enjoyed pastimes as disparate as fishing and taking his staff to the opera.

In short, Weber was colorful.

So maybe it fits that in death he seems as vibrant as he was in life.

The judge died of cancer in 1989, but the federal courthouse legend -- an urban myth, maybe -- is that his ghost roams the fourth floor of the Grant Street building late at night in black robes, especially when contractors have been working on the building.

"That sounds like my husband," said his widow, Berta, of Erie. "He's supervising. He'd certainly be interested in a story like that. He had such a reputation of being a character."

Most everyone in the courthouse has heard talk of the ghost of Judge Weber, although the apparition is apparently as elusive as a CIA spook. Eyewitnesses are hard to come by, too, although dozens of people swear at least one contractor in years past fled the building in fear after a run-in with the judge.

"I've heard about the judge more than once," said building manager Rick Murphy. "I haven't met him yet. But I've been on the fourth floor when the elevator stops, the doors open, then close, and it moves on. And no one has hit the button for the fourth floor. I guess the judge is coming to work."

Except Weber's courtroom was on the eighth floor, not the fourth, but why quibble?

History lesson

The federal courthouse was originally designed to be a postal center.

The courthouse, built during the Depression, is a natural breeding ground for spooky stories, especially among the All Purpose Cleaning Service staff that works all hours of the night. They say they've felt and heard spirits for years on the ninth floor, the fourth floor, the first floor.

"I've heard them call my name," said Janet Evans, a 15-year employee of All Purpose who has had strange experiences in the chambers and courtroom of Judge Donald Lee on the ninth floor. "It's a male voice. He'd say my name while I was running the sweeper. I'd turn around and no one would be there."

None of this is hard to understand once you spend a few hours in the building in the middle of the night.

The basement levels, especially, are full of strange passageways, odd rooms, massive pipes and conduits snaking every which way and plenty of dark corners. Of the upper floors, the fourth is particularly creepy. Ever since GSA removed the P.J. Dick Corp. from a renovation project in the early 1990s after a dispute over the work, the floor has been in a state of disarray, its ceilings gutted, its walls stripped and a scattering of weak light bulbs casting shadows everywhere.

"On the fourth floor there are spots where you will suddenly feel a cold draft, but there aren't any windows or doors open, and the hair on the back of your neck stands up and you say, 'OK, let's just keep moving,' " said Ron Litke, the building's maintenance inspector. "It's spooky up there anyway because it's dark. But there are times when you feel someone is watching you."

The origin of the Judge Weber story is hard to pin down, but it starts on this floor.

Depending on who's telling the tale, it goes something like this:

About five years ago, an electrical contractor was working to install a new fire alarm system. Contractors generally worked at night so they didn't disturb court proceedings. As the man stood on a ladder with his work illuminated by temporary light bulbs hanging from the ceiling, he suddenly saw a figure in a black robe appear beneath him.

"How's it going?" the figure asked, then walked away.

At first the worker thought his partner was playing tricks. But when he saw the robed figure several other times, he fled the floor and told the security officers someone was walking around in a black robe on the fourth floor. They asked him who he thought he saw. The worker went to the eighth floor, where portraits of all the judges who have served in the courthouse are displayed on the wall, and pointed to the picture of Weber.

After that, the man left the building and swore he'd never come back.

He also supposedly wrote a letter about the incident, but finding it is like, well, chasing a ghost. Everyone swears someone wrote something in a log of some sort.

If so, GSA doesn't have it. "Check with the [court security officers]," they say.

The security officers don't have it. "Don't you have anything better to do than chase ghosts?" said one amused guard.

The U.S. Marshals don't have any reports, either, and say they've never even heard the story. (Of course, even if they had, they could neither confirm nor deny it).

Greg Lazar, a GSA electrical engineer who handles projects for the courthouse, has heard the stories from various contractors and subcontractors, but hundreds of them worked in the building in the mid-1990s, and he can't remember which one is supposed to have started the whole thing. Not that he's a big believer in the first place.

Late nights and flickering lights on the fourth floor can make anyone see things. Add in a few strange sounds, which any old building makes, and a healthy dose of imagination and you've got ghosts.

"Any good story gets bigger the longer it goes," Lazar said.

But is any of it true?

Well, kind of.

Kevin McGill, the former building manager who now works in Hartford, Conn., remembers that a contractor did write a letter in which he complained about the working conditions.

"He didn't like the fact that entire sections of the fourth floor were dark," he said. "I guess it creeped him out."

But McGill says the man never mentioned a ghost. Over the years, he figures, the story has mutated in the telling, and somehow Weber got mixed in.

The original contractor, Guardian Technology Inc. of Cleveland, wasn't much help sorting it all out. The company referred calls to its parent, Buckeye Fire Equipment of North Carolina, but officials there said they hadn't heard the story and wouldn't comment on any aspect of the courthouse project because of ongoing litigation. According to GSA, Guardian defaulted on the fire alarm project.

The guys at Miller Electric Construction, which handled the fire alarm installation after Guardian left, heard the story of the ghost when they took over.

They haven't seen any phantom judges, but weird things did happen on the fourth floor about a year ago. John Bateman, the foreman on the job, remembers telling a co-worker the ghost story one night. When the two men went into a small room in the corner, they found law books lining the shelves. Bateman's co-worker picked one up.

"He opens it and puts it on a desk, and the page he opens it to is about a federal case involving his wife," Bateman said. "There must have been 200 or 300 books on the shelves in there, and he picked that one and opened it to that page. I told him the judge did that for him."

The judge might not be alone on four. One longtime cleaning woman said the spirit of a former director of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, which used to be on the floor, is also roaming around. She's felt strange things on nine, too, where doors have been known to open and close on their own.

"I feel them, I know they're there," she said of the spirits. "They don't bother me, but I feel them swishing past."

Maybe one of them is John McIlvaine. A federal judge appointed in 1955, he suffered a heart attack in 1963 in the courtroom now occupied by Judge Donetta Ambrose on the sixth floor. He died on a couch in the office outside the courtroom, making him the only judge of the 48 who have served the Western District of Pennsylvania to die in the courthouse.

But Weber seems to suit the ghost legend best, especially this month. Beyond his personality, he was most noteworthy for ordering the consolidation of five school districts into one to create the Woodland Hills district in 1981. Now, two decades later, a three-week trial is under way in federal court to determine if Woodland Hills should be released from federal oversight.

It would be a fine time for the judge to turn up.

"I would like to come down," says Berta Weber, "and meet him sometime

Does the ghost of U.S. District Judge Gerald J. Weber haunt the federal courthouse? (Peter Diana, Post-Gazette illustration)

When a defense lawyer once argued that his client deserved leniency on the grounds that he had learned his lesson, the judge said, "The only thing that's going to teach him a lesson is when he hears the cold steel bars of the jail cell closing around him."

Despite his pragmatism, U.S. District Judge Gerald R. Weber was smart as a whip, a Harvard graduate, a World War II intelligence officer and a man who enjoyed pastimes as disparate as fishing and taking his staff to the opera.

In short, Weber was colorful.

So maybe it fits that in death he seems as vibrant as he was in life.

The judge died of cancer in 1989, but the federal courthouse legend -- an urban myth, maybe -- is that his ghost roams the fourth floor of the Grant Street building late at night in black robes, especially when contractors have been working on the building.

"That sounds like my husband," said his widow, Berta, of Erie. "He's supervising. He'd certainly be interested in a story like that. He had such a reputation of being a character."

Most everyone in the courthouse has heard talk of the ghost of Judge Weber, although the apparition is apparently as elusive as a CIA spook. Eyewitnesses are hard to come by, too, although dozens of people swear at least one contractor in years past fled the building in fear after a run-in with the judge.

"I've heard about the judge more than once," said building manager Rick Murphy. "I haven't met him yet. But I've been on the fourth floor when the elevator stops, the doors open, then close, and it moves on. And no one has hit the button for the fourth floor. I guess the judge is coming to work."

Except Weber's courtroom was on the eighth floor, not the fourth, but why quibble?

History lesson

The federal courthouse was originally designed to be a postal center.

The courthouse, built during the Depression, is a natural breeding ground for spooky stories, especially among the All Purpose Cleaning Service staff that works all hours of the night. They say they've felt and heard spirits for years on the ninth floor, the fourth floor, the first floor.

"I've heard them call my name," said Janet Evans, a 15-year employee of All Purpose who has had strange experiences in the chambers and courtroom of Judge Donald Lee on the ninth floor. "It's a male voice. He'd say my name while I was running the sweeper. I'd turn around and no one would be there."

None of this is hard to understand once you spend a few hours in the building in the middle of the night.

The basement levels, especially, are full of strange passageways, odd rooms, massive pipes and conduits snaking every which way and plenty of dark corners. Of the upper floors, the fourth is particularly creepy. Ever since GSA removed the P.J. Dick Corp. from a renovation project in the early 1990s after a dispute over the work, the floor has been in a state of disarray, its ceilings gutted, its walls stripped and a scattering of weak light bulbs casting shadows everywhere.

"On the fourth floor there are spots where you will suddenly feel a cold draft, but there aren't any windows or doors open, and the hair on the back of your neck stands up and you say, 'OK, let's just keep moving,' " said Ron Litke, the building's maintenance inspector. "It's spooky up there anyway because it's dark. But there are times when you feel someone is watching you."

The origin of the Judge Weber story is hard to pin down, but it starts on this floor.

Depending on who's telling the tale, it goes something like this:

About five years ago, an electrical contractor was working to install a new fire alarm system. Contractors generally worked at night so they didn't disturb court proceedings. As the man stood on a ladder with his work illuminated by temporary light bulbs hanging from the ceiling, he suddenly saw a figure in a black robe appear beneath him.

"How's it going?" the figure asked, then walked away.

At first the worker thought his partner was playing tricks. But when he saw the robed figure several other times, he fled the floor and told the security officers someone was walking around in a black robe on the fourth floor. They asked him who he thought he saw. The worker went to the eighth floor, where portraits of all the judges who have served in the courthouse are displayed on the wall, and pointed to the picture of Weber.

After that, the man left the building and swore he'd never come back.

He also supposedly wrote a letter about the incident, but finding it is like, well, chasing a ghost. Everyone swears someone wrote something in a log of some sort.

If so, GSA doesn't have it. "Check with the [court security officers]," they say.

The security officers don't have it. "Don't you have anything better to do than chase ghosts?" said one amused guard.

The U.S. Marshals don't have any reports, either, and say they've never even heard the story. (Of course, even if they had, they could neither confirm nor deny it).

Greg Lazar, a GSA electrical engineer who handles projects for the courthouse, has heard the stories from various contractors and subcontractors, but hundreds of them worked in the building in the mid-1990s, and he can't remember which one is supposed to have started the whole thing. Not that he's a big believer in the first place.

Late nights and flickering lights on the fourth floor can make anyone see things. Add in a few strange sounds, which any old building makes, and a healthy dose of imagination and you've got ghosts.

"Any good story gets bigger the longer it goes," Lazar said.

But is any of it true?

Well, kind of.

Kevin McGill, the former building manager who now works in Hartford, Conn., remembers that a contractor did write a letter in which he complained about the working conditions.

"He didn't like the fact that entire sections of the fourth floor were dark," he said. "I guess it creeped him out."

But McGill says the man never mentioned a ghost. Over the years, he figures, the story has mutated in the telling, and somehow Weber got mixed in.

The original contractor, Guardian Technology Inc. of Cleveland, wasn't much help sorting it all out. The company referred calls to its parent, Buckeye Fire Equipment of North Carolina, but officials there said they hadn't heard the story and wouldn't comment on any aspect of the courthouse project because of ongoing litigation. According to GSA, Guardian defaulted on the fire alarm project.

The guys at Miller Electric Construction, which handled the fire alarm installation after Guardian left, heard the story of the ghost when they took over.

They haven't seen any phantom judges, but weird things did happen on the fourth floor about a year ago. John Bateman, the foreman on the job, remembers telling a co-worker the ghost story one night. When the two men went into a small room in the corner, they found law books lining the shelves. Bateman's co-worker picked one up.

"He opens it and puts it on a desk, and the page he opens it to is about a federal case involving his wife," Bateman said. "There must have been 200 or 300 books on the shelves in there, and he picked that one and opened it to that page. I told him the judge did that for him."

The judge might not be alone on four. One longtime cleaning woman said the spirit of a former director of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, which used to be on the floor, is also roaming around. She's felt strange things on nine, too, where doors have been known to open and close on their own.

"I feel them, I know they're there," she said of the spirits. "They don't bother me, but I feel them swishing past."

Maybe one of them is John McIlvaine. A federal judge appointed in 1955, he suffered a heart attack in 1963 in the courtroom now occupied by Judge Donetta Ambrose on the sixth floor. He died on a couch in the office outside the courtroom, making him the only judge of the 48 who have served the Western District of Pennsylvania to die in the courthouse.

But Weber seems to suit the ghost legend best, especially this month. Beyond his personality, he was most noteworthy for ordering the consolidation of five school districts into one to create the Woodland Hills district in 1981. Now, two decades later, a three-week trial is under way in federal court to determine if Woodland Hills should be released from federal oversight.

It would be a fine time for the judge to turn up.

"I would like to come down," says Berta Weber, "and meet him sometime