How Equalization Upsets Equality

Robert Bass

Department of

Philosophy

Coastal Carolina University

Conway, SC

29528

rhbass@gmail.com

Diminishing marginal utility arguments are frequently urged as reasons for equalizing or for moving toward equalization of incomes.1 Perhaps surprisingly, they do not often get much detailed attention. Some find them obviously persuasive -- and say so in about three sentences. Others find them obviously defective -- and dismiss them in about three sentences. (Still others, it may be suspected, avoid discussion of them for fear of finding them persuasive.) As the purpose of the present paper is to examine this line of argument, some work -- more than can be crammed into three sentences -- is necessary to see what is being said and how it works (or doesn't work, as the case may be).

The strategy of the paper is as follows. I think that the diminishing marginal utility argument does not, under normal circumstances, support equalization of incomes. Moreover, the reason that it does not, is integral to the argument under a favorable interpretation. (Among other things, I shall not question the moral appropriateness of the utilitarian assumptions underlying the argument.) I will approach the argument "from the outside in." I will begin with a statement of the argument, then examine and reject (or at least stipulate away) a number of criticisms. Finally, we will be prepared for consideration of the argument itself, favorably interpreted. And under that interpretation, employing very weak assumptions about what is required for the success of the argument, it will be shown to fail in its own terms.

It is best to begin with a sketch of the argument under discussion while leaving open the possibility that it will need refinement or qualification in light of subsequent consideration; such a sketch will at least provide a focus for discussion:

According to this argument, equality is desirable because an egalitarian distribution of economic assets maximizes their aggregate utility. The argument presupposes: (a) for each individual the utility of money invariably diminishes at the margin and (b) with respect to money, or with respect to the things money can buy, the utility functions of all individuals are the same. In other words, the utility provided by or derivable from an nth dollar is the same for everyone, and it is less than the utility for anyone of dollar (n - 1). Unless b were true, a rich man might obtain greater utility than a poor man from an extra dollar. In that case an egalitarian distribution ... would not maximize aggregate utility even if a were true. But given both a and b, it follows that a marginal dollar always brings less utility to a rich person than to one who is less rich. And this entails that total utility must increase when inequality is reduced by giving a dollar to someone poorer than the person from whom it is taken.2

A point that should be obvious from the outset is that, though the argument supports equalization or moves in the direction of equalization of incomes,3 it is not an intrinsically egalitarian argument. That is, it does not appeal to any notion that an equal distribution is better than an unequal distribution independently of consequences4 -- independent specifically of consequences in terms of utility-maximization. If the consequences were different than the argument takes them to be, then it might not turn out to be an argument for equalization. (It might in fact require an unequal distribution or even redistribution away from equality.)

Beyond this obvious point, something needs to be said about what is meant by diminishing marginal utility. Utility, roughly, can be taken to be a measure of the strength of a person's preferences with respect to some outcome.5 Thus, if two different outcomes have the same utility for you, then, if you could not have both, you would be indifferent between them. If one outcome of a pair (when you could not have both) had greater utility for you then that is the one you would choose. If you had to give up something which itself had positive utility for you -- time or money, say -- to get one of the outcomes, you would give up more to obtain the one with the higher utility.

If this is what utility is, what is "the principle of diminishing marginal utility"? What is it doing in the argument? It's really a fairly commonsensical notion. Consider ice-cream. (And suppose that you like ice-cream, i.e., that it has positive utility for you.) A single serving may be delicious. A second serving may be enjoyed. And perhaps a third .... But at some point, one doesn't want any more ice-cream.6 Each additional serving has less utility than the one before. It may be that at some point, the utility derivable from eating more ice cream actually becomes negative or it may be that associated costs, such as discomfort, sickness or expense, outweigh any additional positive utilities derivable from the consumption of more ice cream. Which way we choose to describe the situation probably makes little difference. In either case, one will not continue consumption indefinitely. The example can be generalized or so, at least, economists are inclined to think. That is, for any good from which utility is derived, an additional unit will have less utility than the one before (and may, depending on how the utility function is described, actually result in costs in terms of utility). Importantly, for the sake of the argument under consideration, it applies to money. Each additional dollar is worth less to its recipient than the one before. (This may not be strictly true though it is assumed in Frankfurt's formulation of the argument above. Eventually, this will be attended to, but for the present, it is sufficient if the relation tends to hold.) However, in the case of money, economists typically argue that, however many dollars one may already have, each additional dollar will still confer a positive, though perhaps minute, additional utility since dollars can be exchanged for any of a large range of other goods. (An assumption seems to be at work here that we are not completely satisfiable beings and that our satisfaction can always be increased by some good or other that is available in exchange for dollars.)

Given these points plus the assumption that Frankfurt employs that people's utility functions with respect to money or additional dollars of income are the same,7 the diminishing marginal utility argument for equalization is fairly straightforward. The wealthy man gets less utility out of an additional dollar than does someone who is poor. In fact, he gets less utility out of his most recently acquired dollar than would his poorer neighbor. Hence, equalization.

This, though apparently straightforward, is plainly too fast. At the very least, a ceteris paribus clause needs to be added. If other things are not equal -- if, for example, there are somehow substantial costs (in terms of utility) associated with the necessary transfers -- then the equalization conclusion may not follow. Before considering these issues, however, it's worthwhile to spend a bit of time on some attempts that have been made to prevent the diminishing marginal utility argument from getting off the ground.

The most direct attack on the argument is posed by those who claim that we can't do interpersonal utility comparisons. And since we have to do interpersonal comparisons (in order to establish or support the assumption that people's utility functions are the same with respect to income), the argument fails from the outset. We do not know, on this account, that a transfer from a wealthy man to a poor man increases utility, even if other things are equal. And without that knowledge, we can't give reasons in terms of utility-maximization for making the transfer.8

Though it is plain enough what the bearing of a denial of interpersonal comparisons is on the diminishing marginal utility argument, it is less clear what people mean -- or have meant -- by the denial. The denial itself has been motivated and argued for in different ways, only some of which can be considered here.9 Three (successively weaker) interpretations of the denial stand out. The Outright Denial claims that there is no underlying reality that a utility function describes. A utility function, on this view, is a construct imposed by an observer and based solely upon actual choices.10 The Ordinalist Denial admits an underlying reality on which a utility measure may be based, but claims that this consists solely of ordinally ranked outcomes (or preferences with respect to outcomes).11 The Agnostic Denial does not commit itself to particular claims about the underlying reality of utility functions. It only claims that we cannot know, even if there is a fact of the matter, when one person derives more utility from an outcome than another.12

The Outright Denial is the strongest -- and also the least plausible -- of the three. It certainly rules out interpersonal comparisons: nothing to compare ... therefore, no comparisons. Among other things, it implies that one cannot know anything even about the relative weighting or ranking of one's own preferences at a given time apart from observing how one in fact behaves.13 This seems bizarre.14 It is, at any rate, vastly remote from the ordinary understanding of "preference" in which the preferences one has motivate choices; they are not simply induced from choices. The Outright Denial amounts to a claim that there is "nothing that it is like" to have a preference.

The Ordinalist Denial attempts to rule out interpersonal comparisons by virtue of an argument that one person may prefer A to B while another prefers B to A but that there is no fact of the matter as to whether the preference of one between the two alternatives is greater than or less than the preference of the other. If a wealthy and a poor person both prefer to have one more dollar (over what they already have), there isn't any strength of preference between the alternatives to be measured (or to differ).

The Ordinalist Denial is somewhat more plausible than the Outright Denial. But that may be largely the result of being compared to a position which is itself thoroughly unattractive. It certainly appears introspectively that there is such a thing as strength of preference, that one can judge that one prefers one outcome to another more strongly than one prefers that other to a third outcome. (This can be the case even if we don't have any reliable or precise measures, instruments or operations for determining the difference. Long before there were thermometers, people had reason to think that the relation "warmer than" was not just ordinal.) The Ordinalist has offered no reason to deny this; at most, he may hope to reinterpret it.15

The Agnostic Denial is the most plausible since it does not feel called upon to deny or reinterpret what appears to be the case in introspection. It only claims that we don't know how to do interpersonal comparisons. This is a claim which may be backed up by a challenge. That is, someone who thinks interpersonal comparisons possible can be challenged to explain how, in a particular case, he knows.16 And, in a particular case, especially if the challenger gets to specify the details, there may be no persuasive answer.

Still, the claim that we cannot (ever or justifiably) do interpersonal comparisons is itself deeply unpersuasive. In the first place, none of us acts as if we believe that it is true. Consider, for example, charitable giving.17 If we didn't think we could do interpersonal comparisons, we shouldn't be able to see any difference between giving money to someone who's starving and making out a check to a random millionaire. After all, the millionaire might get more utility out of it.18 For a second example, consider court awards of damages. These amount to attempts on the part of a jury to judge what monetary payments are appropriate to compensate a victim for having suffered some harm. Damage awards are almost always contestable -- in the sense that they are not both clearly and precisely right. But, for almost any particular case that may come before a court, some solutions can be ruled out as plainly wrong. We may not be able to say just what a broken arm is worth but we can certainly say that it is worth more than one and less than a billion dollars. That is, however roughly and inaccurately, we do manage to make interpersonal comparisons.

Second and more deeply, if it is denied that we can do interpersonal comparisons, that will create problems for intrapersonal comparisons.19 Almost no one thinks that it is especially problematic that we can make judgments about the relative strength of our own preferences.20 As Hare notes,

[E]ven if we say nothing about other people's preferences, our whole governance of our lives depends on the solution of a problem of which knowledge of other people's preferences is a special case: the problem of truly and with confidence representing to ourselves experiences which are now absent; for all or nearly all preferences are between experiences, etc., at least one of which is absent.21

There may, of course, be epistemic dificulties connected with interpersonal comparisons which do not apply in the intrapersonal case. That would only imply that we need more evidence or are less reliable or can judge reliably over narrower ranges of cases. But such difficulties do not support the Agnostic Denial. If we can make (reliable, justified) intrapersonal comparisons, then, in principle, we can do the same interpersonally.22, 23

Sometimes the diminishing marginal utility argument is attacked for incorporating and relying upon unrealistic assumptions. Frankfurt, whose outline of the argument was quoted above, says that

both [the assumption that for everyone the utility of money invariably diminishes at the margin and the assumption that people's utility functions with respect to money are the same] are false. Suppose it is conceded, for the sake of the argument, that the maximization of aggregate utility is in its own right a morally important social goal. Even so, it cannot legitimately be inferred that an egalitarian distribution of money must therefore have similar moral importance. For in virtue of the falsity of [the assumptions], the argument linking economic equality to the maximization of aggregate utility is unsound.24

Frankfurt is correct in this, of course, and in fact has more to say about the unrealism of the assumptions. But so far as his argument depends on this claim (that the diminishing marginal utility argument is unsound), it looks as though he has made things too easy for himself.

Lerner, for example, in his 1944 discussion of the argument, didn't make either mistaken assumption. With respect to the sameness of utility functions, he assumes only that "the satisfactions experienced by different people are similar .... [and] that it is not meaningless to say that a satisfaction one individual gets is greater than or less than a satisfaction enjoyed by somebody else."25 With respect to the invariably diminishing marginal utility of incomes (which Lerner takes, some complications apart, to be required for rational choice), he says "it is not necessary ... to suppose that the expenditure of income is always conducted in a perfectly rational manner. As long as some considerable proportion of expenditure is governed by a rational choice of items that yield a greater rather than a smaller satisfaction, the marginal utility of income will in general decline."26

Lerner can afford these weaker assumptions because he is not concerned to have an argument that guarantees that aggregate utility is maximized if incomes are equal. He is only concerned to argue that equal division of income "maximizes the probabletotal of satisfactions in the society."27 His claims are on behalf of a general policy. The argument is one about maximizing expected aggregate utility under conditions of partial uncertainty. If he is validly arguing from good approximations (and if there aren't better approximations available), then, arguably, that's all the support a policy needs.28

So, are the assumptions good approximations? It seems to me, though I shall not argue the matter at length, that they are.29 In the ordinary choices that fall to the lot of each of us -- with respect to charitable giving, damage awards, norms of courtesy, etc. -- we typically do make these assumptions in default of special information to the contrary. If the diminishing marginal utility argument is to be criticized, then attention should be focused elsewhere than on the realism of these assumptions.

Earlier, it was noted that the argument requires a ceteris paribus clause. A large array of objections to the diminishing marginal utility argument has been based on claims to the effect that other things are not equal. There have, in particular, been numerous claims that considerations of efficiency or incentives militate against the argument's egalitarian conclusion. Also mentioned have been considerations about the cost of administering transfers to equalize incomes. If these were sufficiently high, any gains in aggregate utility from equalization might be matched or outweighed by the added costs of a transfer-administering bureaucracy. Such considerations often seem quite plausible. It may be that an economy with equal distribution of incomes would be much poorer than one with certain kinds of inequalities. (It would not be enough just to show that it would be somewhat poorer. Some loss in total incomes could be more than compensated by increased utility derived from income among the net transferrees.)

This is, in part, why I have referred to the argument as an argument for equalization or for moves in the direction of equalization of incomes. If transfers directly or indirectly interfere enough with maximizing aggregate utility, the diminishing marginal utility argument will not require those transfers. (It may not require any transfers if the diminishing marginal utility considerations are completely swamped by efficiency or other concerns.)

However plausibly it might be claimed that, under the conditions of the real world, the ceteris paribus clause is unsatisfied, I do not wish to rely upon such contentions. I am willing to stipulate that the clause is satisfied.

Another line of criticism of the diminishing marginal utility argument claims that it relies upon a zero-sum assumption. It is assumed that the quantity of wealth is static and can only be differently distributed, not increased.30 But in a world in which wealth is not static, and given reasonable assumptions about incentives and/or efficiency, it is entirely possible that total utility will be maximized under an unequal distribution. (It is even possible that everyone's utility will be greater than under an equal distribution.)

Of this sort, I take it, is David Schmidtz's argument that in a world in which production is a possibility, it may be important to leave (or place) assets in the hands of those who get less utility from them and therefore would rather invest than consume them. And resources invested in production can, of course, yield greater future utility.31 This is a special case of the general point that a sum over the outcomes of a set of maximizing operations is not necessarily a maximal sum -- and is, I think, entirely correct.

Nonetheless, correct though it is, I will not avail myself of it. There is a still deeper problem with the diminishing marginal utility argument. To see what it is, I will stipulate away these considerations.

Thus far, I have rejected or stipulated away a variety of criticisms of or objections to the diminishing marginal utility argument. What remains?

Imagine a community in which utility functions for all members are similar but not identical.

Assume also that it is generally true that incomes have diminishing marginal utility. (If it were assumed that utility functions were identical or that additional income always has declining marginal utility, then the argument would be subject to Frankfurt's objection that the assumptions are false.)

Assume that the community has a stable population so that no complications are introduced by expanding or declining population.

Assume that it is not the case that total wealth is liable to any substantial increase or decrease due to exogenous shocks.

Assume that there are no efficiency, incentive or transaction-cost problems with a policy of equalization.

Assume that the wealth of the community (and therefore, total real incomes) can be described as zero-sum in the following sense: Total wealth is insensitive to and will remain approximately the same regardless of distributive arrangements. This needs to be spelled out a bit more fully. There is a sense in which wealth can't be insensitive to distributive arrangements. For human beings are inevitably consumers. Therefore, in a world of limited (immediately consumable) resources, they must also be producers or suffer progressive impoverishment. Total wealth will not be insensitive to total work done, so distributive arrangements cannot be divorced from a requirement that a certain amount of work be done. (To avoid complications, I shall omit or assume away any disutilities that may derive from resentment against a labor requirement.)

Labor, as will be discussed further, must be viewed, over some range of cases, as having increasing marginal disutility -- and hence will count as a cost to be offset against the utility derivable from income. Since we are only assuming that utility functions are similar rather than identical, and since there will not be a precise way of determining what each person's utility function is, it is reasonable to suppose that a Lerneresque argument would support, for a relevant class of approximately equally capable laborers, an equal labor requirement.32

It appears that Lerner's argument would apply here in full force. The best policy that could be adopted with respect to income distribution would be one of equalization. Does that settle matters? It does not.

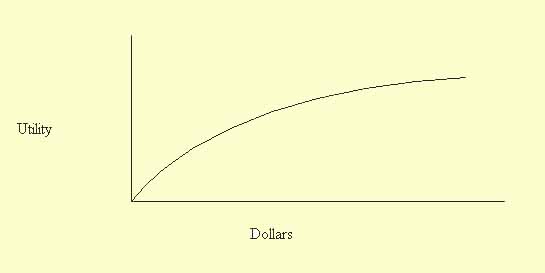

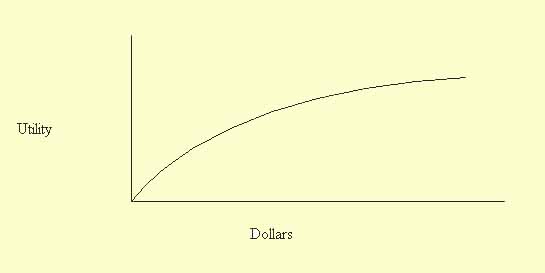

In general, people will have to work to acquire incomes. That is, they will exchange time, effort and the products of their talents for the incomes they receive. (Call what is exchanged, 'labor.') Since they will have diminishing marginal utility for income, the relation between the incomes they receive and the utility derived from them can be represented in this way:

Each increment in income will be accompanied by an increase in utility though the increase will be less at higher ranges of income than at lower. We approach an important question here: If a person can exchange additional labor for additional income, why would that person ever stop working? She is, after all, better off in terms of utility for each marginal increment of income. If diminishing marginal utility for income is all that counts, there is no answer. It could be suggested that sheer physical incapacity may intervene. She does not labor further because she cannot. But this is no help in most cases. People do not normally work (for income) to the limits of their capacity. What else is involved?

Briefly, it can be said that her utility function for marginal increases in income is not all that is involved. Labor may be tiresome, boring, repetitive, demanding. Other things than labor may be attractive, fulfilling, pleasant. In some range of cases, labor normally has increasing marginal disutility. That is, one's desire or willingness to labor further decreases and may become negative as the amount of labor increases. This is equivalent to saying that, as the quantity of labor rises (in the relevant range of cases), one would attach an increasingly high utility to the option of ceasing to labor.

As the utility that can be derived from ceasing to labor -- that is, ultimately, from the available alternatives to labor -- becomes sufficiently high, it will exceed the utility derivable from additional income that could be received in exchange for labor. Here, we can explain why the worker who gets additional utility for each marginal dollar received would nevertheless stop working. She will stop when the utility derivable from ceasing to labor exceeds the utility derivable from additional income.33

It might be said that these considerations, resting on the assumption that incomes may differ according to labor, are not relevant to the equal-income world we have been imagining. But this would be a mistake. Even if people cannot alter their incomes by working more or less, the underlying utility functions for income and for labor will still exist and will still determine the actual utilities workers derive from income. (If they did not, then that would undermine the diminishing marginal utility argument.)

Since it is not being assumed that people's utility functions are exactly the same, some will have more rapidly diminishing marginal utility for income than others. They will, correlatively, have more rapidly increasing marginal disutility for labor than others. We have been assuming that all work the same amount and receive the same income. This amounts to the employment, in the imagined equal-income community, of an average utility function. Actual utility functions will vary around the average, but the best that the equal-income distribution policy can achieve is to disburse income and labor requirements in accordance with the average.

The utility functions of some, it may be assumed, will exactly match or not significantly diverge from the average utility function on which the standard work requirement and income disbursement is based. But notice what is implied about all the other members of the community. Consider the person whose rate of diminishing marginal utility for income is higher. He would, if he had the choice, have stopped working before the standard work requirement was met even if he also had to accept a reduced income in order to do so. His utility gain for marginal income past the point at which he would have stopped working is exceeded by his utility loss from the marginal disutility of (further) labor. Or, consider the person whose rate of diminishing marginal utility for income is lower than the standard. If she had the choice, she would have continued working in exchange for additional income past the fulfillment of the standard work requirement. Her reduced loss of utility from the marginal disutility of labor up to the point at which she would have stopped working is exceeded by her utility loss from foregone income. Only those whose utility functions exactly (or almost exactly) match the asumptions embodied in the equal incomes and work requirements prevalent in this community are as well off. No one is better off. Everyone else is worse off.

To put this differently, it is likely that many workers would have a reason to engage in exchanges of money for labor or of labor for money to improve their total utility. Those who have too much money (compared to the labor they are required to perform to receive it) will pay those who have too little money (compared to the labor they are required to perform) to do work for them. Differences in income will reflect utility-maximizing decisions of workers. A person who has a higher rate of diminishing marginal utility for income will tend to have a lower income. But this does not imply that he is worse off in terms of utility. Similarly, a person who has a lower rate of diminishing marginal utility for income will tend to have a higher income. But this does not imply that she is better off with respect to utility. An observer, attending to objective inputs or costs and rewards could say that one chose to pay reduced costs in labor and accept reduced monetary rewards while the other chose to pay increased costs in labor for increased monetary rewards. Both will have made a utility-maximizing decision. The result will be an unequal but Pareto-superior distribution of income.34

More broadly, consider the two possibilities: an equal and an unequal income distribution with an efficient labor market. If the distribution is equal (and utility functions are not the same), people will have reasons to move away from it. If the distribution is unequal, they will not have reason to redistribute to achieve complete equality. And if, perchance, people's utility functions are such that an equal distribution really does maximize aggregate utility, then people will, in an efficient labor market, move toward that -- even if there is no agency that concerns itself with arranging an equal distribution.35 There may be no better income-distribution policy than equal shares; that does not mean that there is nothing better than an income-distribution policy.

If the argument here is correct -- if, that is, there is not even under favorable assumptions a diminishing-marginal-utility-based case for equalizing incomes, then the conditions or objections stipulated to be satisfied or avoided may have even more weight than their proponents have thought. If there are any legitimate concerns about, say, efficiency or incentives, in the equal-income society, they are surely even more relevant if the case for equalization is flawed when those considerations are absent.

Diminishing marginal utility considerations may be quite appropriate for the distribution of largesse by an external benefactor. It may be very plausible, in such circumstances, to distribute so as to equalize or move in the direction of equalizing incomes or assets. But governments in real economies are not external benefactors and what they have to distribute is not (normally) externally provided largesse.36

[1] Arguments of this type will, for convenience, be referred to as "the diminishing marginal utility argument," or sometimes, where the context makes it clear, just "the argument."

[2] Harry Frankfurt, "Equality as a Moral Ideal," Ethics 98 (October 1987), pp. 24f. As stated, the argument applies to "economic assets." To simplify discussion, I will refer primarily to incomes.

[3] In subsequent cases, I will use "equalization" as an abbreviation for the phrase, "equalization or moves toward equalization of incomes (or wealth)." I will use "equalizing incomes" in a parallel way and will not spell these out at length except where it seems to have a bearing on the argument.

[4] This may be a too restrictive understanding of what is implied by or required for egalitarian arguments. One might wish to say that someone who reaches egalitarian conclusions just is an egalitarian, regardless of the manner in which those conclusions are reached. However, this can be treated as a terminological issue which need not be settled here. The point of the distinction -- which is not merely terminological -- appears in the text.

[5] This is only a rough equivalent. Other rough equivalents that have been suggested are pleasure and preference-satisfaction. A formal treatment, perhaps not exactly captured by any of these, can be provided in terms of a Von Neumann-Morgenstern "utility function" which is a measure of a person's preferences on a constructed interval scale and requires that the person's preferences meet a set of conditions assumed or argued to be necessary if the person is to be rational.

[6] That is, one doesn't want any more to eat at that time. But one might want a carton to put in one's freezer for later. Or two cartons. Or three. But at some point ....

[7] This does not seem to be strictly true though it is assumed in Frankfurt's presentation. But, like the claim about invariably diminishing marginal utility, I think it tends to be true and thus is a useful approximation. Whether it upsets the argument will come in for attention later.

[8] This statement is too strong. It might be, that we do not, in a particular case, know that a transfer will increase aggregate utility, but do know that such transfers would normally or generally increase utility. If what is under consideration is only the single transfer, then ignorance about its outcome would be a reason not to make it (on utility-maximizing grounds -- though there might be other reasons for making it). But if what is under consideration is a policy of transfers from the wealthier to the poorer, our ignorance about the particular case would not undermine it.

However, the partisans of "no interpersonal comparisons" would find this remark beside the point, even if technically correct: How, they would ask, without interpersonal comparisons, are we ever to know "that such transfers would normally or generally increase utility"?

[9] For a survey of some of these, see Lawrence H. White, "Is There an Economics of Interpersonal Comparisons?" (Manuscript, 1994).

[10] "...[T]he scale of values or wants manifests itself only in the reality of action. These scales have no independent existence apart from the actual behavior of individuals. The only source from which our knowledge concerning these scales is derived is the observation of a man's actions. Every action is always in perfect agreement with the scale of values or wants because these scales are nothing but an instrument for the interpretation of a man's acting" (emphasis added). Ludwig von Mises, Human Action (Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1963 [3rd rev. ed.]), p. 95. Curiously -- and inconsistently -- the same author also expresses a version of the Ordinalist Denial. See note 11.

[11] "A judgment of value does not measure, it arranges in a scale of degrees, it grades. It is expressive of an order of preference and sequence, but not expressive of measure and weight. Only the ordinal numbers can be applied to it, but not the cardinal numbers." Mises, p. 97.

[12] I have not found a straightforward statement of the Agnostic Denial. It seems to be a fall-back position that people adopt when pushed with regard to the weakness of the Outright and Ordinalist Denials.

[13] Perhaps, if the Outright Denial is correct, one could still form hypotheses(based on prior experience) about what one's preferences are, i.e., about how, in different circumstances, one would act.

[14] One is reminded of the story of two behaviorists in post-coital conversation: "It was wonderful for you, darling. How was it for me?"

[15] Assume a reinterpretation succeeds. Presumably that would mean that we have a large array of ordinally stated preferences over sets of outcomes that differ only slightly from their neighbors. Our judgments about the relative strengths of preferences would then be, essentially, comparative estimates of how many ordinal rankings intervened between the compared outcomes. In effect, we would have identified a perhaps multi-dimensional measure of the minimum difference in the world that makes a difference in our preference orderings. (If there is any other way to reinterpret experienced strengths of preferences so that they refer to or are expressive of nothing but ordinal rankings, I don't see what it is.) It doesn't seem that this would undermine ordinary comparative judgments any more than the atomic theory undermined ordinary comparative judgments about length or volume.

[16] This is sometimes, confusedly, defended with a claim to the effect that we sometimes or often get things wrong when we attempt interpersonal comparisons. But, in order to know that we get things wrong, we would have to sometimes get things right. A related confusion is involved in the claim that our fallibility with respect to interpersonal comparisons shows that we don't really know, that we're just guessing. But, leaving aside any criticisms based on diagnosis of the former confusion, it is simply not true that fallibility entails that we don't know anything. There are any number of fields -- as examples, meteorology and medical diagnosis -- in which we can do much better than chance but still make frequent errors.

[17] Leave aside questions about why people who think interpersonal comparisons impossible would do any charitable giving.

[18] No doubt a story could be constructed in which it is actually plausible to say that the millionaire gets more utility from the gift than the person who's starving. But -- and this is at least a large part of the point -- a story would have to be constructed. In the absence of special circumstances, we are almost all convinced that the starving person gets more from a gift of the same dollar amount than would the millionaire.

[19] This point is discussed in R. M. Hare, Moral Thinking (Oxford: Clarendon, 1981), pp. 124-128.

[20] E. F. McClennen has pointed out to me that there may be problems as difficult and intractable as those associated with interpersonal comparisons in dealing with intrapersonal comparisons over time. In fact, the latter problem might be viewed as just another case of interpersonal comparison -- comparison between the preferences of time-defined selves. This may somewhat weaken or reduce the scope of the point that I, following Hare, was making, but I do not think that it completely eviscerates it. Hare's point refers to absent experiences -- and these may be experiences about which a person could have a present preference and which could be had conditional upon a present choice. If we can ever be reliable or justified in our preferences, even in such a restricted case, it seems that we can't simply rule out the possibility that we can be reliable or justified in making interpersonal comparisons.

[21] Hare, p. 126.

[22] We can, that is, unless we adopt skepticism about other minds.

[23] It might be argued that intrapersonal comparisons are unproblematic (in a way that interpersonal comparisons are problematic) because they are comparisons among states or possible states of ourselves. I don't think this objection can go through, but for the present it is sufficient to note that, if it is to carry weight, a great deal of elaboration is needed. It is just a tautology that intrapersonal comparisons are between states of the comparer while interpersonal comparisons are not (or not entirely). But adding a tautology to an account that doesn't generate a given conclusion will not make it generate that conclusion. What is needed is a plausible account of personal identity at a time and over time that would explain such privileged access.

[24] Frankfurt, p. 25.

[25] Abba P. Lerner, The Economics of Control (New York: Augustus Kelly, 1970 [1944]), p. 25.

[26] Ibid., p. 34.

[27] Ibid., p. 34.

[28] Lerner can admit, as he does, that "[i]f we knew the effect in every particular case it is virtually certain that an unequal division of income would be the best possible, but in the absence of this unattainable knowledge [the] conclusion in terms of probabilities still holds." Ibid., p. 37.

[29] Of course, the argument could be upset if there were utility monsters in the relevant population. But that's a common issue for utilitarian arguments. It doesn't obviously have a special bearing on this argument.

[30] Actually, I think this assumption is not necessary for the diminishing marginal utility argument to have force, though little rests on the point. What may be necessary is an assumption to the effect that total wealth is relatively independent of what people do. It is not crucial that wealth be static, only that total quantities of wealth (and therefore of utility derivable from wealth) not be significantly reduced under some distributive arrangements as compared to others.

[31] "Diminishing Marginal Utility" (Manuscript, 1995).

[32] There need not, however, be some sort of one-to-one matching where a single unit of income is tied directly to a single unit of supplied labor.

[33] This could be described differently, of course. For example, the utility derived from income could have included these factors. Then, at some point, it would have to be shown as declining -- i.e., marginal income would have negative utility. Then, the worker would cease laboring when marginal income ceased to have positive utility.

[34] More generally, any distributive arrangement which disburses incomes and requires some quantity of labor (whether egalitarian or not) but (a) is significantly insensitive to people's actual utility functions and (b) consequently leaves some receiving more income than they would prefer, given that they are also required to perform more labor than they would prefer in order to receive it and leaves others receiving less income than they would prefer if they could perform additional labor in order to receive it can be transformed into a different distribution by Pareto-efficient moves. (I said "significantly insensitive" because I am not assuming that the transaction and information costs for such exchanges are zero.)

Certain criticisms may be made of this argument. In particular, it may be claimed that the assumptions of equal abilities and an efficient labor market are misleading idealizations. Idealizations they certainly are; whether they are misleading is a different question. For, whatever aid and comfort they may give to inegalitarians, it seems that they or something very much like them are also needed by the diminishing marginal utility argument if it is to be at all plausible that equalizing incomes will not have unacceptably high costs in economic efficiency.

[35] This is significant because it has been assumed that there are no transaction costs associated with a redistributive program or agency. As there plainly are transaction costs in the real world, the fact that an equal distribution would come about anyway if it were utility-maximizing, seems to be decisive against such redistributive programs or agencies.

[36] What implications might diminishing marginal utility considerations have under realistic (not idealized) conditions? First, and most obviously, they would appear to support moves to increase the efficiency of markets. Second, they might support some sort of minimum income guarantee for those whose capacity for labor is significantly below average. Third, it should be noted that the purpose of this paper has not been to deny that there may be some reason for a policy of equalizing incomes; only to deny that diminishing marginal utility arguments supply that reason. (And, of course, if other sorts of arguments are admitted, it cannot be a foregone conclusion that they will support equalizing policies. Considerations of what is "earned" or "deserved" in particular may support inegalitarian conclusions.)