Coinage

Claudius’ portraits show he was not an unattractive person. Notions that Claudius was too homely or grotesque in appearance to be portrayed accurately on his coinage ignores comments that he was pleasant to behold (Claud. 30.) He closely resembled his uncle Tiberius, except Claudius had a broader skull. His neck muscles are noticeably over developed which may be the result of his effort to control the trembling of his head. Claudius’ earliest portraits as emperor display the fiction of the eternal youth imagery of Augustus, which was reflected on coin portraiture. However, Claudius moved away from idealized portraits to show himself as he looked in life. The most famous of these statues is the full-length portrait of the emperor as Jupiter from Lanuvium. This portrait shows us a man in his fifties with bags under his eyes, jowls and a furrowed forehead, presenting a stark contrast to the youthful, well-muscled body. The hair in this portrait is the typical Julio-Claudian layered hair with comma-shaped locks, parted near the center.

Claudius’ coinage can be divided into two groups based upon his usage of the title pater patriae. Although he received the title in January 42, Claudius did not introduce P.P into his titles on his gold and silver coins until 46, and it did not become universal until 51. Claudius never used the praenomen imperatoris but he allowed its use as a cognomen with the number of imperial salutations as they increased (to 27 at the time of his death.)

The coinage Claudius introduced to commemorate his family occurs at the beginning of his reign when he wished to point up his famous father, mother and brother. The coins issued in the name of his father Nero Claudius Drusus were in gold, silver and bronze. The aurii and denarii recall the German victories by depicting a triumphal arch inscribed: DE GERM(ANIS) along with another type depicting crossed oblong shields, spears and trumpets. A sestertius was issued depicting Claudius on the reverse seated amid a pile of miscellaneous weapons which may have been intended to show the son sharing in the honors of his father.

Antonia is depicted on gold and silver coins wearing a corn-wreath with her hair in long plaits, being presented in the guise of Ceres. [1] One reverse depicts Antonia as Constantia, holding a torch. This depiction, with the meaning of constancy, may denote the long widowhood of Claudius’ mother but the inscription CONSTANTIAE AVGVSTI (which should be AVGVSTAE if Antonia is meant) refers to Claudius. Another type depicts two long torches linked by ribbons with the legend SACERDOC DIVI AVGVSTI, which may refer to the dignity of the Vestals granted to Antonia by Gaius when she received the title Augusta. The dupondius issued of Antonia shows her bare headed with long plaits. The reverse bears an inscription of Claudius with the emperor depicted standing, veiled and togate, holding a simpulum.

Claudius also honored Germanicus and his wife, Agrippina with coins in their named. These are conventional depictions following the commemorative issue of Gaius. A dupondius was struck in the name of Divus Augustus with a reverse showing Livia seated, holding corn-ears and a long torch. This may depict the statue Claudius erected of his grandmother following her deification.

Gold and Silver Types

CONSTANTIAE AVGVSTI. This type depicts the figure of constancy or perseverance seated, touching her face with her right hand. This reverse type appears to be a very personal one for Claudius himself enduring his many years of neglect by his family calling upon his endurance or constancy.

An important type for its propaganda value is: IMPER(ATOR) RECEPT(OS). The praetorian camp is depicted as a circular structure. The wall of the camp with two portals bears the coin inscription like a frieze. The inside wall would not be visible to an observer and so is elevated with the camp tower between the wall sections. The wall is shown properly squared off and the gates roughly correspond to the via decumanus and via principalis cross. The sentry on guard is a colossus towering above the troop quarters and the eagle-topped standard is likewise far too tall. Like many architectural depictions this one is illogical and represents the best the die-cutter could do to convey the meaning.

Another type expressing similar sentiments is: PRAETOR(IANUS) RECEPT(US). The emperor, wearing a toga and standing, gives his right hand to one of the praetorians who holds an eagle. Claudius is depicted accepting the fealty of the praetorians, which was later translated into the clasped hands device. With this and the prior type, Claudius advertised that his power had come first from the soldiers and not from the Senate.

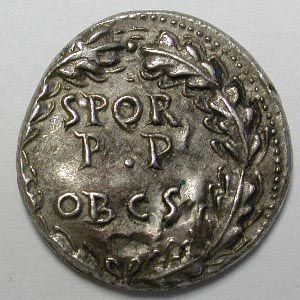

EX S. C. /OB CIVES /SERVATOS and S.P.Q.R./P P/OBCS (issued on awarding Claudius the title pater patriae.) The reverse records that awarding of the corona civica by the Senate to Claudius for his forbearance in sparing the lives of the members who conspired to kill Gaius. The inscriptions are set in three lines within the oak leaf crown.

PACI AVGVSTAE. This intriguing type represents Nemesis, an avenger of crimes, here in the guise of Victory. The figure holds a caduceus, more typical of Pax or Felicitas, but the presence of wings include the idea of Victory; a snake is positioned before the figure. In this type, the power to punish has been supplanted by self-restraint. It recalls the virtue of Claudius in refraining from punishing those who plotted against him and justly deserved to be condemned but were forgiven.

DE BRITANN. This type was issued to commemorate the conquest of Britain. Depicted is a three portal triumphal arch surmounted by an equestrian statue with trophies on either side, similar to the arch depicted on the coins of Nero Claudius Drusus.

Bronze Types

SPES AVGVSTA. The appearance of Spes (Hope) is doubtlessly connected to the birth of Claudius’ son, Britannicus, on February 13, 41. This is the first time Spes was used for dynastic purposes and would occur frequently among later emperors. This coin was restored by Titus and Domitian.

CONSTANTIAE AVGVSTI. This type occurs on an As and is related to the gold and silver issues. Here, however, the figure of constancy differs. The figure of a woman wearing a helmet is standing, attired in a garment reaching to her knees with a cloak flowing behind. The right hand touches her face. A military meaning can be drawn from this depiction of constancy representing courage.

LIBERATVS AVGVSTA. Liberty is shown holding the familiar pileus in her right hand but does not have a scepter. This was a regular and important issue for Claudius symbolizing the restoration of freedom after the excesses of Gaius and the promise of good government provided by the emperor. This type is one in a long line of similar representations that would later become LIBERATVS PVBLICA under Galba.

CERES AVGVSTA. Ceres is seated on an ornamental throne and is holding corn-ears and a long torch. The issuance of this type recalls Claudius’ concerns over the corn supply. It was restored by Titus.

SC with Minerva. Against a bare background the goddess Minerva is seen fully armed in a fighting stance. Minerva was a suitable patron for Claudius representing wisdom and soldierly action. This coin was restored by both Titus and Domitian.

From 51 until 54, gold and silver coins were issued by Claudius in the names of Agrippina and Nero. Agrippina appears on her coinage wearing a crown of corn-ears, her hair arranged in a long plait reminiscent of Antonia’s portrait. A true innovation in Claudius’ coinage occurred when the portraits of Agrippina and Nero appear as reverse types. These coins clearly declare the partnership between the emperor and empress and mark Nero for the succession. Of official issues, Britannicus’ portrait is limited to appearing with Octavia and his half-sister Antonia on coins issued in Cappadocia in 46. [2] Britannicus was well represented in provincial coinage.

Cistophori

The reign of Claudius marks the first issues of cistophori since Augustus, but they were not struck in large quantities and so are rare. The cistophori bearing the join portraits of Claudius and Agrippina and the coins struck in Agrippina’s name are the only ones that can be assigned a date (from 50-54.) The most significant of Claudius’ cistophori shows the temple of Artemis Ephesia, with the inscription DIAN EPHE. The reverse shows an interesting detail in the pediment of three rectangles. The surviving fragments of the temple, one of the wonders of the ancient world, are not complete enough to provide an answer as the use of these rectangles. This reverse of Claudius, when considered with a similar reverse of a coin issued by Hadrian, show that these rectangles were openings that could be closed by wooden shutters. So, a coin of Claudius helped determine an important architectural feature. [3]

Conclusion

Claudius’ reign marks a turning point for the principate. Augustus converted the powers bestowed on him at various times, capitalizing on his success in the civil war, to create the position of princeps (leading citizen.) Tiberius received the same powers but refused to adopt the name Augustus (constantly refusing pater patriae as well) and acted as a private citizen who happened to have distinguishing powers. Gaius received all of the powers of his predecessors at a blow (having held only the questorship) from the Senate after being saluted emperor by the praetorians. Claudius, too, had been emperor for one day before the Senate voted him all significant powers, and this practice became the usual procedure: the principate had become a single office.

Although the emperor’s freedmen had always been important figures at court under Claudius they assumed greater authority and the imperial bureaucracy grew, becoming a governing body in its own right. There must have been senators who were offended by having to deal with Claudius’ Greek freedmen, which is no doubt behind the many slurs found in the writings of the ancient historians. Modern scholars see Claudius differently than ancient historians as being in control and not controlled by his wives and freedmen.[4] Traditionally, Roman men insisted that the place of women be in the home tending to domestic matters. They were fearful of a strong woman exerting power, such as Livia, who was in the eyes of Suetonius, Tacitus and Dio lusted insatiably after power.

Claudius appears to have had a less chauvinistic opinion of women and accepted his wives as partners in power. Even so, he refused Messalina the title of Augusta, possible because it would set a precedent. Agrippina was allowed the title because of her position within the imperial family. But the paranoid attitude of Roman men would not allow Claudius to be a partner in power, he had to be weak and subject to the whims of his wives rather than accept such a partnership. The various political executions that took place during his reign occurred from the ruthless necessity to maintain his regime.

Claudius has received blame for selecting such an unsuitable youth as Nero for the succession and abandoning his own son. This is a hindsight view. The popularity of Nero was at the root of his selection. He could not be denied his place in the succession because of his blood connection to Augustus; in short, he was the only person who could succeed Claudius and not be challenged. The evidence that Claudius abandoned Britannicus is slim. He was a political realist who understood the fragility of his regime and the necessity for the popular Nero to have his place in the succession as Britannicus’ colleague. There was little else that Claudius could do for his son except insist on his rightful position.

The character of Claudius remains an enigma. Fictional accounts paint him in terms too glowing and ancient sources present us with a bloodthirsty tyrant. What emerges from a closer study is an intelligent and capable man who was an efficient manager of the Roman empire. As emperor, he displayed a ruthless side placing the security of his principate first. This has made Claudius open to criticism of being arbitrary and cruel but until he married Agrippina the possibility of a successful coup was very real.

The rebellion of Scribonianus frightened Claudius into the reality that he could easily fall victim to a conspiracy, so it was better to err on the side of maintaining security. The notion that he enjoyed seeing physical pain, particularly during gladiatorial shows, is an exaggeration to make him callous and cruel (Claud. 34.) All that can be said in this vein is that Claudius possessed the human frailty of loosing his temper, a fault that he found worthy of reprimand in himself. In short, he was a rational man who acted in what he hoped were the best interests of the empire and his family.

Claudius set a standard of conduct for his successors as to the concerns of a paternalistic autocracy: keep the people fed and entertained, maintain public works, reward the army, try to keep good relations with the Senate, rely on you amici for advice and provide for the succession. As the Roman empire continued to expand and age, the role of emperor Claudius set for his successors marks him as the first true Roman emperor.

© David A. Wend 1999

Footnotes

1 For an analysis of the hair style of Antonia and Agrippina, see Tameanko, Marvin,"The evolution of the empresses’ hairdos on Roman coinage from Augustus to Constantine: Part I," The Celator (May, 1997), 32-42.

2 Sutherland, C.H.V.,The Roman Imperial Coinage:Augustus to Vitellius,(Spink and Sons, 1984), p. 120.

3 Grant, Michael, Roman History From Coins, (Cambridge University Press, 1958), pp. 64-5.

4 Barrett, op. cit., p.76.