Assassination

Domitian was murdered as the result of a palace

conspiracy on September 18, 96. Ironically, the conspirators were not noble but came from

the very heart of his household. The plot had been carefully planed leaving no doubt that

the time and place were chosen with deliberation. Suetonius (Dom. 17) gives the

most detailed account of Domitian's assassination, received in part from a boy present

during the murder who was attending to the Lares shrine. He names Parthenius (a highly

influential chamberlain who was allowed to carry a sword) as the organizer of the plot

(16.2) and Stephanus, the steward of his niece Domitilla. Other conspirators were

Clodianus, Satur (a head chamberlain and Parthenius's freedman), Maximus and an unnamed

gladiator. Dio names Stephanus and Parthenius as conspirators and includes Segeras and

Entellus, not mentioned by Suetonius (Dio 67.15-16). He adds that the plot had the

support of the praetorian prefects Petronius Secundus and Norbanus and names Domitia as

knowing about the conspiracy. It would have been impossible for the conspiracy to succeed

if at least one of the prefects had not been involved.

Domitian was murdered as the result of a palace

conspiracy on September 18, 96. Ironically, the conspirators were not noble but came from

the very heart of his household. The plot had been carefully planed leaving no doubt that

the time and place were chosen with deliberation. Suetonius (Dom. 17) gives the

most detailed account of Domitian's assassination, received in part from a boy present

during the murder who was attending to the Lares shrine. He names Parthenius (a highly

influential chamberlain who was allowed to carry a sword) as the organizer of the plot

(16.2) and Stephanus, the steward of his niece Domitilla. Other conspirators were

Clodianus, Satur (a head chamberlain and Parthenius's freedman), Maximus and an unnamed

gladiator. Dio names Stephanus and Parthenius as conspirators and includes Segeras and

Entellus, not mentioned by Suetonius (Dio 67.15-16). He adds that the plot had the

support of the praetorian prefects Petronius Secundus and Norbanus and names Domitia as

knowing about the conspiracy. It would have been impossible for the conspiracy to succeed

if at least one of the prefects had not been involved.

The murder took place around midday. Domitian had foreknowledge of the

hour of his death, fearing the fifth hour.[1] When Domitian asked the time of day from an

unnamed servant he was given the wrong time (Dom. 16.1). Put off-guard, Domitian

was unsuspecting when Stephanus asked urgently to see the emperor with information

regarding a conspiracy. While the emperor read a document Stephanus gave him, the steward

stabbed him in the groin with a dagger concealed on his left arm by bandages from a mock

injury. Domitian fought back, disarming Stephanus and injuring his assailant. Domitian

called to the boy to give him a dagger kept hidden under a pillow but the weapon had had

its blade removed. The remaining conspirators were close by and rushed the emperor when

they realized Stephanus was in trouble, stabbing Domitian seven more times.

The probable pretext for the conspiracy was the execution of Flavius

Clemens and Domitian's secretary Epaphroditus, who had been Nero's secretary and helped

him to commit suicide (Nero 49). Domitian's increasingly suspicious nature had

alarmed his courtiers to protect themselves. On the part of Stephanus, revenge for the

execution of Clemens and exile of Domitilla may have been a factor. Dio gives the reason

for the assassination that Domitian had "conceived a desire" to kill the

conspirators and had written their names on a tablet of linden-wood, which was discovered

and given to Domitia (Dio 67.15.3). An improbable scenario. Later, Dio more

pragmatically says the executions of Flavius Clemens and Epaphroditus (67.14.4)

precipitated the assassination. Suetonius gives as reasons that Domitian had executed

senators (Dom. 10-11), he was too rigorous in the enforcement of his financial

policy (Dom. 12) and his increasing arrogance (Dom. 13.) Although Domitia is

not mention by Suetonius, she may have realized that political reality dictated the death

of her husband. Whatever her role, 25 years later she continued to refer to herself as

"Domitian's wife" when she could have avoided it. (Corpus Inscriptionum

Latinarum 15.548a-9d). Procopius also recorded an act of her devotion when Domitia

ordered a statue of her husband to be made (Secret History 8.12-22).

Nerva, also, is not mentioned by Suetonius but Dio says he was fully

informed. Philostratus suggests that Nerva conspired with Apollonius of Tyana against

Domitian (Vita Apol. 7.8, 20, 32) but this is certainly a fabrication. He was not

the nominee of the Senate being chosen by the praetorian prefect after discussing the

subject with a number of men who did not accept, as they thought their loyalty was being

tested (Dio 67.15.5). Why did Nerva accept without question? It is apparent that he

knew in advance of the assassination.

Nerva had connections to the principate on both sides of his family. His

uncle, also named M. Coccieus Nerva, had accompanied Tiberius into exile. He had a slender

relationship to the Julio-Claudians through his mother, Sergia Plautilla. Nerva was a

favorite of Nerva for his elegies and was one of four men the emperor rewarded for

services revealing Piso's conspiracy (Annals 15.72.1-5). He received the same

honors as Tigellinus, the praetorian prefect and enjoyed the exceptional honor of having

his portrait in the palace. For unspecified services for Vespasian during the Civil War

Nerva was granted the rare privilege of an ordinary consulship with the emperor in 71, the

only time Vespasian did not hold the consulship with Titus. Then, for loyal services

during the revolt of Saturninus in 89, Nerva held an ordinary consulship with Domitian in

90. His career was otherwise undistinguished; he had not been an visible figure but lived

a quiet life content to have influence at court, behind the scenes. Nerva had made himself

indispensable because of a network of spies and informers that kept him abreast of events.

Uncharacteristically, Nerva chose to back himself rather than remain loyal

to Domitian. Stories that his life was in danger and that he suffered exile are

fabrications created to disassociate himself with his predecessor (Vita Apol. 7.8; De

Caes. 12; Dio 67.15.5-6.) However, Nerva was a committed Flavian and as emperor

maintained good relations with the pro-Domitian faction in the Senate, and was notorious

for it (Letters 4.22). For the conspirators Nerva was a perfect choice as emperor

postponing a possible power struggle between generals, such as Trajan (who was governor of

Upper Germany), and he was old, sick and childless.[2]

†

Conclusion

In his study of Tiberius, Domitian probably came across the comment that

being in control of the state was like holding a wolf by the ears. The message was clear:

relaxation of power brings disaster. Domitianís display of magnificence was little

different from Augustus promoting his regime, although the princeps was more flexible in

dealing with the Senate. Vespasian, too, had worked with the Senate but dominated the

senators by keeping ordinary consulships in his family to firmly establish a dynasty.

Domitian took the office of emperor to its logical progression: autocracy. As the third

member of his dynasty, power had been established among the Flavians, so pleasing the

Senate was not a concern. Although the powers of the Senate were minimal they guarded

their privileges and were alarmed at being reduced to merely assenting to Domitian's

policy, and threatened by the admitting of new members who owed allegiance only to the

emperor. In spite of this, Domitian granted honors to even his most implacable enemies. If

Domitian was heavy-handed when wielding power he also possessed a sense of duty and skill

at governing that cannot be underestimated.

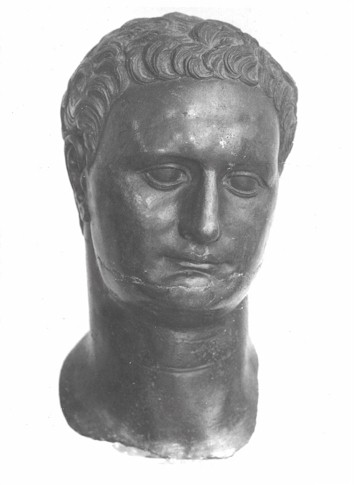

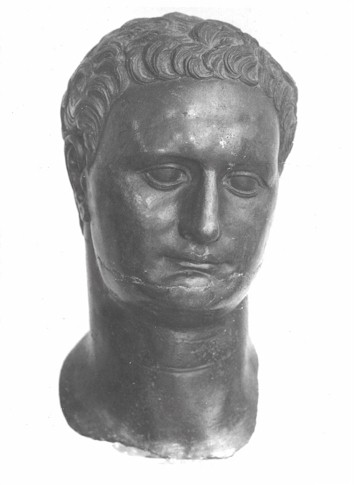

Domitian is described as tall and reasonably handsome with a tendency to

blush (Dom. 18). Like his father he became bald as he aged and wrote a pamphlet

titled The Care of the Hair, in which he quoted a line from the Iliad on the

short-lived quality of beauty. His choice of words indicates that Domitian was a realist.

Martial made reference to Domitianís baldness in a poem (5.49) and suffered no bad

effects from the comment, so the emperor can be said to have had a tolerant disposition.

Rather than being sexually promiscuous, he seems to have been something of a prude.

Domitian refused to kiss the hand of Caenis, his fatherís mistress, disapproving of

her relationship with his father. His enforcement of morality laws followed the example of

Augustus in upholding traditional virtues. The message on the extant portions of the

frieze of the Temple of Minerva in Domitianís forum is clear that duty, the

assumption of oneís proper place in society and obedience were the virtues the

emperor wished to instill.

Domitian spent about three years on campaign, at the time a substantial

period spent outside Rome.[3] He has been criticized for needless military exploits and

incompetence in the loss of legions and the treaty with Decebalus. Instead,

Domitianís military policy reflects his careful management of the empire. The

situation on the Danube became critical with Roman troops faced with fighting on more than

one front. Had there been more coordination on the part of the Germanic tribes and the

Dacianís the frontier could have been breached. By paying off the Dacians and

attempting to set one tribe against the other, Domitian sought to save the situation as

best he could. Fighting one enemy at a time was better than being overwhelmed!

The military situation on the Danube made it necessary to remove forces

from Scotland, giving up some conquered territory. This was a sound decision that future

emperors followed in turn. There was little in Britain the made it cost-effective to

conquer. Domitian was heaped with criticism for his decision but he must be credited with

the good sense to realize his military priority was elsewhere. Agricola had the glory of

conquering Britain but not the good sense to realize it was not worth it.

A sense of his sophistication is found in his devotion to the arts, by

surrounding himself with poets, creating beautiful buildings with his architect, Rabirius,

and his devotion to Greek culture.

Domitian was a solitary individual in contrast to his gregarious father

and brother. To his contemporaries, this need to disappear from the public eye fostered

opinions of a cold-blooded autocrat who spent his time torturing flies. But the need for

solitude is different from adopting the life of a recluse. Domitian separated his private

life from his public duties, as evidenced by the construction of a palace with clearly

defined areas for both aspects of his life. His relationship with his family is impossible

to gauge. His greatest affection seems to have been for only Domitia, particularly since

the empress remained faithful to the memory of her husband. Julia Titi remained resident

in the imperial palace during her widowhood, indicating she was not on bad terms with her

uncle. While a love affair with Julia is possible there is no evidence to suggest that it

ever happened. Toward Vespasian and Titus, Domitian performed his duty; seeing to the

deification of his brother, completing family building projects and establishing a cult

temple. There is no evidence either way to suggest good or bad feelings among them. It is

unknown what Domitian may have felt for his sister, Domitilla, his mother and his uncle,

T. Flavius Sabinus.

Domitianís obsessive devotion to Minerva has been considered a

substitute for an absent mother, however, the goddess suited the aims of Domitian

particularly well. The Sabine country, the ancestral home of the Flavians, was the place

of origin for Minervaís cult and the palladium, one of the goddessí

emblems, was associated as the symbolic transmission of power during the empire. The

goddess had a martial aspect that suited Domitianís military actions and she

represented the duties of domestic life (through spinning and weaving) and civic duty to

the state.

Domitian was an authoritarian figure for whom people were a means to an

end. The elaborate facade of grandeur that he built for the office of emperor has been

impossible to breach to find the man behind the mask. His morality was strict and

punitive, as was his inflexible application of the rule of law. A quote of Domitian that

nobody believes in conspiracies until the emperor is dead reveals the paranoia that

motivated him, particularly following the rebellion of Saturninus. Greater security,

however, was his ultimate undoing. It is ironic that Domitianís courtiers were those

who murdered him, fearful of the unpredictable nature of their master, while the Senate

remained impotent to take action.

After Domitianís death, aristocratic members of the Senate rejoiced.

They saw to it that a damnatio memoria that was passed but this measure appears to

have had mixed results. Only 37% of Domitianís extant inscriptions throughout the

empire were re-cut.[4] The reign of Nerva, in contrast, was greeted as a restoration of

liberty. But his fellow-consul, Fronto, had the last word on his colleague remarking,

"that it was bad to have an emperor under whom nobody was permitted to do anything,

but worse to have one under whom everybody was permitted to do everything." (Dio

68.1.3).

Domitian was murdered as the result of a palace

conspiracy on September 18, 96. Ironically, the conspirators were not noble but came from

the very heart of his household. The plot had been carefully planed leaving no doubt that

the time and place were chosen with deliberation. Suetonius (Dom. 17) gives the

most detailed account of Domitian's assassination, received in part from a boy present

during the murder who was attending to the Lares shrine. He names Parthenius (a highly

influential chamberlain who was allowed to carry a sword) as the organizer of the plot

(16.2) and Stephanus, the steward of his niece Domitilla. Other conspirators were

Clodianus, Satur (a head chamberlain and Parthenius's freedman), Maximus and an unnamed

gladiator. Dio names Stephanus and Parthenius as conspirators and includes Segeras and

Entellus, not mentioned by Suetonius (Dio 67.15-16). He adds that the plot had the

support of the praetorian prefects Petronius Secundus and Norbanus and names Domitia as

knowing about the conspiracy. It would have been impossible for the conspiracy to succeed

if at least one of the prefects had not been involved.

Domitian was murdered as the result of a palace

conspiracy on September 18, 96. Ironically, the conspirators were not noble but came from

the very heart of his household. The plot had been carefully planed leaving no doubt that

the time and place were chosen with deliberation. Suetonius (Dom. 17) gives the

most detailed account of Domitian's assassination, received in part from a boy present

during the murder who was attending to the Lares shrine. He names Parthenius (a highly

influential chamberlain who was allowed to carry a sword) as the organizer of the plot

(16.2) and Stephanus, the steward of his niece Domitilla. Other conspirators were

Clodianus, Satur (a head chamberlain and Parthenius's freedman), Maximus and an unnamed

gladiator. Dio names Stephanus and Parthenius as conspirators and includes Segeras and

Entellus, not mentioned by Suetonius (Dio 67.15-16). He adds that the plot had the

support of the praetorian prefects Petronius Secundus and Norbanus and names Domitia as

knowing about the conspiracy. It would have been impossible for the conspiracy to succeed

if at least one of the prefects had not been involved.