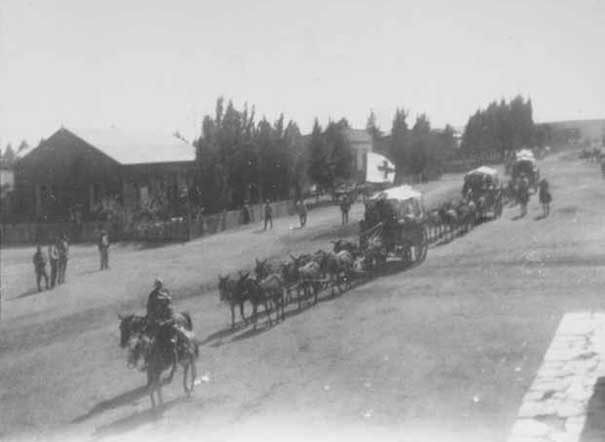

Ambulance during Anglo-Boer War

Photo supplied by Alwyn P Smit

Back to home Back to Historical

The

Van Rensburg's of Rensburg Siding, Colesberg, Cape part

1

The Anglo-Boer War Introduction

part 2

The Anglo-Boer War around

Rensburg Siding: Boer Leaders part 3

The Anglo-Boer War around

Rensburg Siding Nov 1899 part

4

The

Anglo-Boer War around Rensburg Siding Dec 1899 part

5

The

Anglo-Boer War around Rensburg Siding Jan 1900 part

6

The Anglo-Boer War around Rensburg Siding Feb 1900 part 7

The

Anglo-Boer War in retrospect part

8

Australian units, persons and casualties part

9

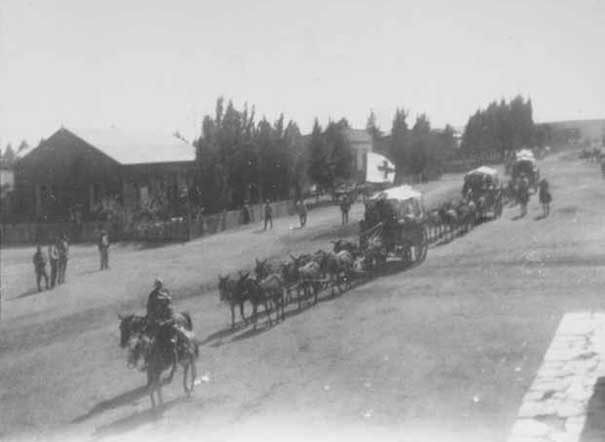

MAIN

MAP source http://www.mjvn.co.za/anglo-boer/mainmap1.jpg

The Anglo-Boer War: Australians capture De Wet's artillery gun at Rensburgdrift part 10

Page 1 Page 2

The

Anglo-Boer War around Rensburg Siding

February 1900

On 31st January and 1st February General French returned to Rensburg Siding, and started to withdraw some of the cavalry regiments, including the NZ regiment to Modder River.

Celliers

in his diary makes mention that on Thursday 1st February 1900 he went and visited

the Boer hospital at Colesberg. Dr Gustav A Mangold was chief of staff at the

hospital. Before his arrival at Colesberg, Dr Mangold was the head of the Johannesburg

division of the Red Cross. During November 1899 Mangold was sent to Norvalspont

with a support team and medical equipment. At Colesberg Mangold was appointed

the head of a field ambulance and three hospitals. Celliers description of the

hospital: "Men heeft groote luchtige zalen voor die zieken en gewonden

uitgezocht, operatiekamers enz., alles in volmaakte orde. Indien wij ver van

een dorp in het veld hadden moeten kampeeren zouden wij zulk een mooie gelegenheid

niet gehad hebben voor onze hospitalen. In andere opzichten is de nabijheid

van het dorp weer niet goed, daar het ons moeite kost de manschappen er uit

te houden en tot dienst te bepalen. Wij maakte kennis met de vrouw van den dominé

[Most likely the spouse of the reverend G.A. Scoltz]; zij gaf ons een mandje

vruchten mee. Colesberg heeft prachtige tuinen, nergens zag ik nog zulke groote

moerbeien- en vijgenboomen". [Huge hall-like rooms were kept aside for

the wounded. We were fortunate to be near town, and not in the open veldt. Being

near town however, led to various problems with the burghers. We met the wife

of the local church minister and she gave us a basket with fruit. Colesberg

had beautiful gardens with the loveliest mulberry and fig trees]

Oorlogsdagboek van Jan F. E. Celliers 1899 - 1902, p. 64. 1 Februarie 1900

(Dond.).

See J. C. Roos, "Het Transchvaalsche Roode Kruis" gedurende die

Tweede Vryheidsoorlog 1899 - 1902, pp. 47 - 51, 153;

Staatscourant der ZAR 19(1083), 06.12.1899, p. 1752;

TAB, RK 4(13) Rooikruis......: rapport van dr. Mangold, 11.12.1899.

Ambulance during Anglo-Boer War

Photo supplied by Alwyn P Smit

The Boer Forces at beginning of February: General H Schoeman - 4,680 men, 2 Krupp guns, 2 Armstrongs and 4 Maxims, spread over a 18 miles front.

3,000 of these

were defending the front line -

Under Grobler: 400 on the Boer right, and 200 at Colesberg Bridge,

De la Rey and 1,080 men were on the left flank defending the railway line and

the dust wagon route to Norvals Pont.

The numbers by Piet de Wet's Orange Free staters is not known.

The English Forces at the beginning of February: 5,275 men with 14 guns.

400

artillary men consisting of - 4th Battery had six 15 pounders; J Battery had

six 12 pounders; 37th Battery had 2 Howitzers.

3,300 infantry - 2nd Bedfordshires - 1st Royal Irish - 2nd Worcestershires -

2nd Wiltshires - One batallion Royal Berkshires.

1 550 were cavalry regiments - 2 squadrens 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons - 490

Australian Mounted Infantry - 175 Victorian Mounted Infantry & 44 Australians

Infantry and Remingtons Guides.

History of the War in SA vol 1, p 407 68-69, and Die geskiedenis

van die Tweede Vryheidsoorlog in Suid-Afrika, 1899 -1902, IV, p 145.

Celliers gives

some interesting insights into the Boers from the cities who were totally out

of place in the veldt, fighting the English.

Celliers-dagboek pp. 65 en 66. 2 Febr. 1900 (Vr): Er zijn in onze

lagers zekere mooie jongens uit de steden zich tusschen onze Boertjies gevoelen

als visschen op het drooge. De mooie kleeren heeft mijnheer meegebracht, de

hagelwitte gesteven halsboorden en manschetten. Op de kleeren van dezen mijnheer

is niet één vetkolletje te bespeuren, en als hij de hoed afneemt,

o, wat een zoete geur, en hoe mooi en steil dat haar aan die eenen kant opgeborsteld,

en aan den anderen kant plat neergeplakt met het meest correcte en schoonste

paadje er door.

Zelfst de zalonstap is niet vergeten en oefent nog de oude kracht wanneer er

dames voorbeijkomen. Want je moet niet denken dat zulk kostelijk vleesch geschapen

is om in de kliprandjes en het veld vernield te worden door zonnebranden en

nachtkoude! Hemel, hoe zou het portret er dan wel uitzien dat mijnheer wil laten

maken als hij thuiskomt, met geweer in de hand, patroonbandolier om de schouders

en de houding van: het is volbracht, en hier ziet gij het hoogsteigen werktuig?

En, bovendien, wat, als een kogel het een onmogelijk maakte voor de menschheid

om ooit zulk een portret te zien te krijgen? Maar ach en helaas, hoe blind zijn

de menschen, en van alle menschen het ergst, de Boer op commando! Zoo werd mijnheer

aangezegt dat hij het dorp moest vaarwel zeggen voor het lager niet zonder verlof

mocht verlaten, en dienst moest doen als andere burgers. Verbeeld je, een Professor

(!) of B.A. onder orders van een lot Boeren! Mijnheer stoorde zich eenvoudig

niet aan het opdracht, Maar op een gegeven oogenblik hoort hij aan de deur te

kloppen, twee ruwe Boeren met geweren in de hand verzoeken mijnheer om hen te

volgen. Wat wil mijnheer doen? Hij gaat nog even naar binnen om zijn haar in

orde te maken, oefent zich voor den spiegel in het zetten van een martelaarsgezicht

en geeft zich dan over, onverschrokken, perfect in houding en kleeding, aan

de geleide van het "canaille".

Zoo vonden wij hem, Commandant en ik, in de tent waar het verhoor zou plaatsvinden.

Met het eene been een weinig naar achteren, zoodat alleen de teen op ten grond

rustte, de eene hand in de zij, zoo stond hij daar, als een standbeeld van de

"gemartelde hoogstwaardigheid". Het verhoor bracht mijnheer vreeselijk

in het nauw, en zijn verdediging was eene aaneenschakeling van uitvlugten, die

elkaar zóó tegenspraken dat wij (o, zonde!) ons lachen onmogelijk

bedwingen konden. De angstzweet stond op zijn voorhoofd. In een zalvende, bijna

huildende kinderstem -- doch nog altijd een zeer fijn fabicaat -- drukte de

knaap zijn verbazing uit dat zijn "lieve" en "achtbare"

Commandant zoo hard op hem neerkwam; het was toch de eerste keer; nooit zou

er weer een klacht zijn enz. enz.

Als tegenover een kind dat beeft voor den stok, zoo sloeg het medelijden onzen

Commandant om het hart: en het end was, dat onze "dandy" met een vermaning

vrij kwam. Buiten de tent stonden de Boertjes wachten, ala zwaluwen die uil

bij daglicht vervolgen. Van hun theater verwijderd en overgeplaatst in een smeltkroes

als het commandoleven, waar karakters onvermijdelijk bllotgelegd worden, waar

ruw doch raak geoordeeld wordt, daar hebben zulke heertjes het zwaar te verduren.

en dat lijden houdt niet op, want, als een schooljongen, is de Commandomensch

onverbiddelijk, en het heerschapje kan met den besten wil van de wereld zijn

fatsoen niet weer veranderen.

In den namiddag had de begrafenis plaats van een onzer krijgsmakkers (zekere

De Villiers)[Johannes Hercules de Villiers from Pretoria. Staatscourant der

ZAR 20(1096), 14.02.1900. p.119.] die aan typhuskoorts in het hospitaal overleden

was. Het roodekruis wagen werd als lijkkoets gebruikt opdat de vijand niet op

ons schieten zou. Buiten de stad, aan de noordzijde, is onze begraafplaats en

daar voerden wij hem heen. Alleen wij, zijn krijgskameraden, stonden om het

graf daar geen familielid ergens in de nabijheid was.

[In short: The youngsters from the cities brought along their best clothing

and looked like fish on dry ground. Their hair were still in shape and they

always tried to impress the young ladies in town. These young men were not born

to be fighters in the kopjes and have their beautiful skin burnt in the hot

sun. The commandant more than once scolded them and this made them tremble with

fear. Ultimately they had to adapt to the harsh conditions and become the same

as the rest of all the men. In the afternoon the burial of De Villers took place.

He died in hospital, suffering from the ever present typhus fever. We used the

Red Cross wagon, knowing that the enemy won't shoot at us. Our cemetery was

to the north of town and only the fighting burghers were at the grave, as no

family were near]

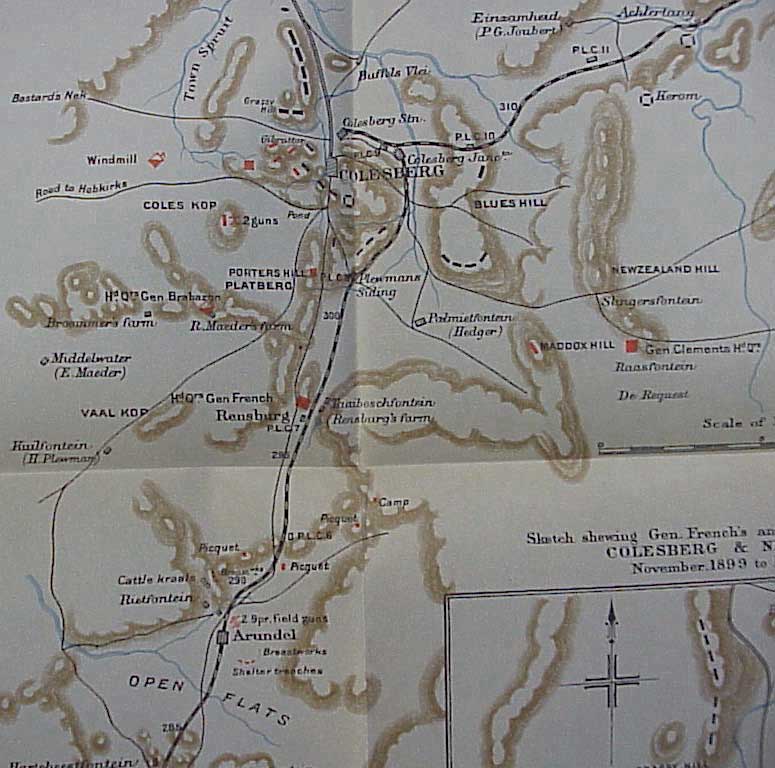

On Monday 5th February 1900 General Clements moved from Slingersfontein to Rensburg

Siding, to take over command from General French.

On the same day according to Celliers, the English were bombing them and the

Boers also bombed the English as they came within range. He refers to one Boer

Maxim gun which killed 5 English and severely wounded one. They were killed

to the right of Coleskop on the route which the wagons used. The casualties

on the English side were observed with a pair of binoculars. Celliers-dagboek

p.66. 5 Februari 1900 (M)

British

Howitzers shelled Boer positions north of Madocks Hill.

5th February: Most of the cavalry, The New Zealand Mounted Infantry who had

faught under Captain WRN Madocks R A, and all French's original forces withdrew

with French. He left behind a smaller, less mobile force, to cover a front over

30 miles in extent. They were as follows: A Squadron of Inniskilling Dragoons

under Lieut. NW Haig, 200 West Australian Mounted Infantry under Captain HG

Moor, half a battalion of the Royal Berkshire Regiment, 4 guns of the J Battery

RHA - the 4th Battery RFA took position on the west side of Colesberg. Also

on the west side at this time, Lieutenant Smith's 2 Howitzers of the 37th Battery

and about 1,000 Colonial troops which he felt was a strong enough force to contain

the Boers in their Colesberg position. General Clements, now in charge, had

to try and carry out this plan with a depleted force. He adopted a strategy

of "bluff" moving troops around at night and staying out of site during

the day. To support the infantry, mule-wagons were kept ready to move out at

any given moment.

General Clements

on Monday February 5th 1900 moved from Slingersfontein to Rensburg Siding,

to take over command from General French

On Wednesday 7th February Celliers writes about how the Boer Maxim gun was shelling the English at Coleskop: "Vroeg in den morgen begon onze maxim al zijn doef-doef-doef te laten hooren en Commandant riep ons op te staan en ons gereed te houden. Ik ging boven op ons kliprandje zitten met mijn kijker en kon de bommen van die maxim boven op Coleskop sien barsten. Later bedaard alles weer". [Early in the morning the maxim gun opened fire and the commandant asked us to be on the alert. I went to the top of the rocky hill and through my binoculars I could see the shells bursting over Coleskop] The next day it was the Boers turn to be shelled by the English. Oorlogsdagboek van Jan F. E. Celliers 1899 - 1902, p. 67, 68.

Thursday the 8th February - Boers attacked the Britsh left, seizing Bastard's Nek.

On

the 9th February 1900 the English rained lyddite bombs on the Boers Maxim, and

three Boers manning the Maxim were slightly wounded. In the afternoon the bombs

came flying again from Coleskop right across the Boers tents. Celliers describes

the sound of the bombs as the sound of a strong wind passing through the strings

of a harp, "De bomscherven en kogeltjes vloten en schreeuen met een geluid

als van een sterken wind door harpsnaren". Oorlogsdagboek

van Jan F. E. Celliers 1899 - 1902, p. 68.

Celliers describes how wonderful it was to be on commando for 3 or 4 months.

He does not need to worry the problems of every day life, no debt collectors,

no financial worries. "In een maand geven wij hier dikwijls niet meer dan

een shilling uit". It is like reliving ones childhood without the want

to posses or spend anything. Celliers-dagboek p. 68, 69.

10 Febr. 1900: He refers to the frustration caused by waiting and doing nothing on the Boer burghers. More and more of them request leave and every excuse is offered. Then there are others who are over keen to get into battle and want to take up arms without the knowledge of their leaders. He comments that as the days progress it is more difficult to keep order amongst the restless burghers. He then refers to a Chinese proverb: "a dog couped up in its cage gets annoyed by fleas but a dog on the hunt is not even aware of fleas". Or in Dutch "de hond in zijn hok wordt door zijn vlooien geplaagd, de hond op jacht voelt zijn vlooien niet". Oorlogsdagboek van Jan F. E. Celliers 1899 - 1902, p. 68.

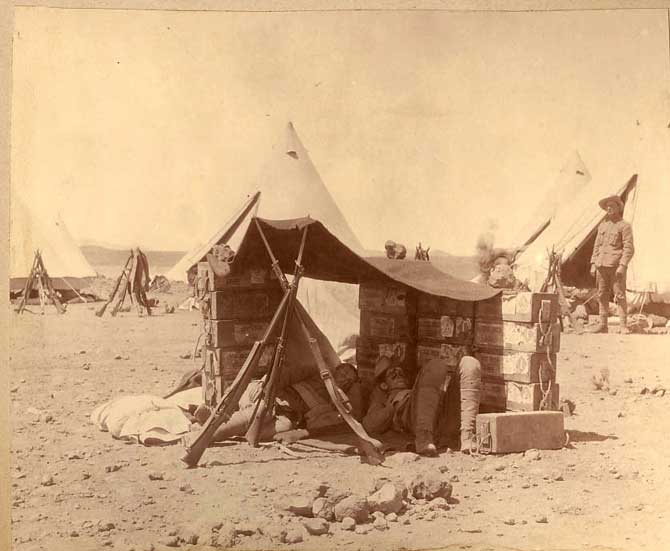

English soldiers resting in a shelter made for shade, probably near Britstown,

not far from Colesberg

Photo supplied by Alwyn P Smit

Celliers

shares how he wished on 10th February 1900 that life only constituted one big

peaceful commando family, provided by the government of the day! "Het

leven heeft ons zat gemaakt van het geld en zijne beslommeringen; en wat mij

betreft, ik zou den dag toejuichen die het mogelijk zou maken voor de Regeering

om het heele volk in een voortdurend, vredevol, Commando-familie leven te onderhouden".

Apart from being bored they also enjoyed playing games. Celliers records on

Monday 6 February 1900: "Wij reden in den namiddag naar den Generaal. Een

partij zijner manschappen waren bezig zich te vermaken met een karwats. Ieder

die dit in handen kon krijgen deelde slagen uit aan wie hij wilde, tot de karwats

hem door een ander ontrukt werd, en dan kwam hij zelf weer eens aan de beurt

om te ontvangen. De Generaal zelf deed lustig mee; hij deelde goed uit, doch

ontving ook behoorlijk zijn portie. Wij moesten lachen om den Commandant, die

met allerlei bokkessprongen zich achter de paarden zocht te bergen, terwijl

de Generaal hem met de karwats vervolgde".

The sport and fun which the Boers enjoyed, even between their leaders and men were completely opposite to the formal disciplinarian way the English operated. The Boer leader were previous friends and neighbours, this caused a lack of respect and break down of authority within the Boer ranks. This was a major drawback within the Boer force, lack of discipline and respect for authority. As understood from the Dutch paragraph above, within the Boers camp they were playing a game of hitting one another with a riding-whip. Some of the men were chasing their commander through the camp, trying to hit him with the riding-whip. This kind of fun and interaction would never have taken place, nor would have been allowed to take place, amongst the English soldiers. It is hard to imagine English soldiers chasing General French trying to hit him with a riding-whip.

Discipline among the British were far more strict. In his diary Celliers even mentions an instance where an English POW said that he wished that he had been caught earlier by the Boers, since life was much easier for him as a POW of the Boers than under his own strict and austere English commander.

English with

flags signaling from Hospital Hill to New Zealand Hill 7 February 1900

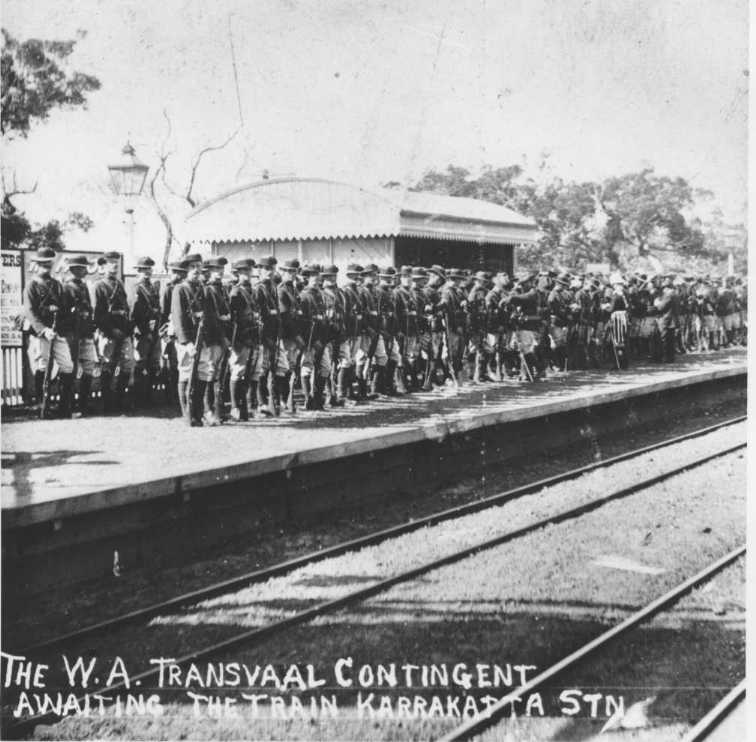

West Australian

Transvaal Contingent lining up on Karrakatta station, near Perth, 7th November

1899

http://www.briggs13.fsnet.co.uk/fw.htm

Australian

Hill / Stubb Hill

On 9th Febuary a small British force which had gone out reconnoiting to Potfontein

narrowly escaped being cut off by De la Rey and Celliers, who pressed after

them to the Oorlog's Poort Spruit, taking a few prisoners and threatening a

further advance to the rear of Slingersfontein. As a result a company of Worcesters,

under Major FW Stubbs, occupied a hill (Stubbs Hill) on the left bank of the

Spruit. Next day Celliers attacked the hill. He was repulsed, but De

la Rey's real goal was to ascertain the strength of the English force and he

thus discovered that they were far weaker. He informed Pretoria, and also indicated

to them that he was going to launch a big attack. He decided to be cautious

at first and assess the situation further. On the 9th February Celliers's men

crossed the Oorlog's Poort Spruit. A group of Tasmanians, under Captain Cameron,

who had come from Jasfontein, were ambushed. They then dismounted behind

the nearest rocky outcrop and managed to hold off the Boers until the rest of

the men were under cover. Sergeant Edwards and two troopers escaped. The English

were driven with some loss from the hills near Vergelegen Farm, and

the Boers took control of these hills.

A party of about 27 West Australians under Major Moor, plus Inniskilling dragoons occupying a small hill were ambushed by Boers who came up the back of a long low ridge of higher ground opposite their position and got within 20 yards of the Australians. The West Australian Sergeant Hensman, badly wounded in both legs, called out: "They have broken both legs, for God's sake, some one come and help me - I am bleeding to death". Private Alexander Kruger (also spelt Krygger) (born in Ballarat, Victoria but moved to Western Australia) crept to him while under fire. He built a schans using stones around him, and placed bushes over his face to protect him from the sun. A certain Conway came to assist and he was shot dead. Kruger also used Hensman's rifle as a splint around both legs. That night they came with an ambulance crew and got the badly wounded Hensman. Hensman later died on 12th March in a Cape Town hospital. Kruger was recommended for a Victoria Cross, but it was not awarded. He contracted enteric fever and was sent back to Australia on 20th August 1900.

A schans used by the English during the Anglo-Boer War, probably learnt

from the Boers.

Note the soldiers on the left.

Photo supplied by Alwyn P Smit

In the meantime as the Australians were retreating, Atherley Gilham and Alfred Button were killed and four others were taken captive. VS Peers from Zeehan, Tasmania, his horse stopped by a wire fence, ran up the hill with two Boers in hot pursuit. Moments later Peers shot them both. He then went looking for the two Boer's horses. In so doing, he came across a third Boer, and both of them took a shot at one another at the very same time. The Boer hit the ground severely wounded and Peers himself received a grazing wound to the neck. Peers however, still managed to shoot a fourth Boer. He then had to take cover and by night was able to make his way back to the camp.

Moor (later killed at Palmietfontein on 18th July 1900) managed to hold the Boers off throughout the following day until help in the form of 2 guns of J Battery R.H.A arrived. This enabled Captain Moor to get his men safely back to camp at dusk. J Battery was said to have expended 514 shells that day. Since then the kopje was known as Australian Hill. On the English side two men died and five were wounded in this skirmish. The Boers lost about 12 men. Afterwards the 20 West Australians and their leader, Captain Hatherly George Moor, were praised by General Clements for their stand against 300-400 Boers near Slingersfontein.

The movements of De la Rey were directed towards the right side. On February 9th and 10th the mounted patrols, principally the Tasmanians, the Australians, and the Inniskillings, came in contact with the Boers, and some skirmishing ensued, with no heavy loss upon either side. A British patrol was surrounded and lost eleven prisoners, Tasmanians and Guides. On the 12th the Boer turning movement developed itself, and the "English" position to the right at Slingersfontein was strongly attacked.

The key of the British position at this point was a kopje held by three companies of the 2nd Worcester Regiment. Upon this the Boers made a fierce onslaught, but were as fiercely repelled. They came up in the dark between the set of moon and rise of sun, as they had done at the great assault on Ladysmith (Natal), and the first dim light saw them in the advanced sangars. In general the Boer commanders did not favour night attacks, but despite the fact they were still exceedingly fond of using darkness for taking up a good position and pushing onwards as soon as it was possible to see. This is what they also did upon this occasion, and the first intimation which the outposts had of their presence was the rush of feet and loom of figures in the cold misty light of dawn. The occupants of the sangars were killed to a man, and the assailants rushed onwards. As the sun topped the line of the veldt half the kopje was in their possession. Shouting and firing, they kept pressing onwards.

But the Worcester men were steady old soldiers, and the battalion contained no less than four hundred and fifty marksmen in its ranks. Of these the companies upon the hill had their due proportion, and their fire was so accurate that the Boers found themselves unable to advance any further. Through the long day a desperate duel was maintained between the two lines of riflemen. Colonel Cuningham and Major Stubbs were killed while endeavouring to recover the ground which had been lost. http://www.hovawart.dogs.sk/sitemap/file0278.htm

Major Arthur Kennedy Stubbs of the 2nd Worcestershire Regt were killed in action

at Rensburg Siding 12th February 1900. He was only aged 32 at the time. Arthur

was the son of Major-General F.W. Stubbs (Royal Artillery), born December 1867

at Meerut, India. His memorial can be seen at Worcester Hill, Yardley Farm,

South Africa

Also Colonel Cuningham of the Worcesters also died at Worcester Hill, Yardley Farm.

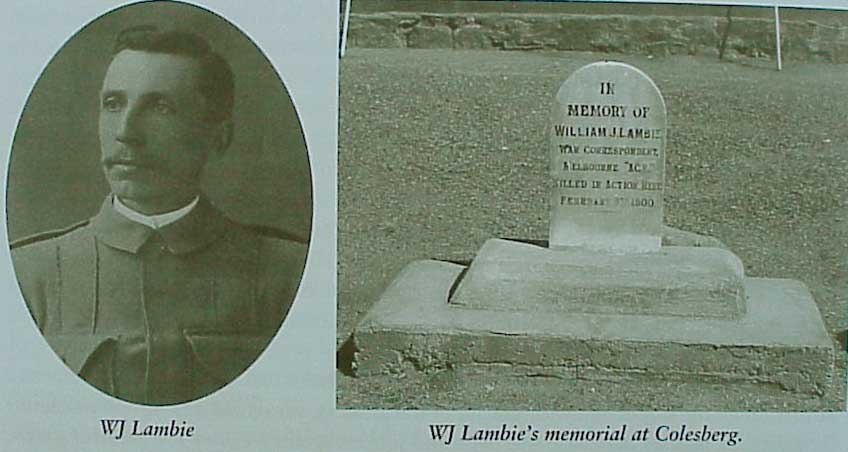

WJ Lambie war

correspondent for the Melbourne Age

shot at Rensburg 9 February 1900

Australian

Journalist shot

Mr Hales and Mr Lambie, two war correspondents, were riding behind the Australians

when on 9th February an Australian patrol made up of 30 Victorians and 18 Tasmanians

left Rensburg base. AG (Smiler) Hales, a Western Australian journalist with

the London Daily News, and William J Lambie the correspondent of Melbourne

Age, accompanied this patrol. The objective was to determine the strength

of the Boers south of Rensburg Siding. The group split in two with the Tasmanians

and journalist going ahead. They were ambushed, and surrounded by about 40 Boer

horsemen. They were told to surrender, but foolishly the journalist ignored

it and made a dash for the safety of the British lines. "All of them were

galloping in on us shooting as they rode and shouting to us to surrender, and

had we been wise men we should have thrown up our hands, for it was almost hopeless

to try and ride through the rain of lead that whistled around us", wrote

Hales. Lambie was hit in the head and died instantly. Hales was also knocked

off his horse by a bullet that grazed his temple. He was taken prisoner and

later released. (The Boers released thousands of English

during the war, due to the fact that they simply did not have the means to keep

them as POW. In short supply of fresh clothing, the Boers often took their khaki

uniforms and let them go in their underclothes).

When Hales came to, he found himself in a Boer camp. Later Hales reported, "They

looked rough but were exceedingly kind. They carried him under a shady tree

and carefully bounded his wounds". The next day FB Heritage under a white

flag approached the Boers seeking information about the missing journalists.

General de la Rey gave him Lambie's watch and other small items, including a

photo of his wife. Heritage took it to his commander Cyril Cameron. De la Rey

also offered captain Cameron safe conduct to the spot where Lambie were layed

buried. When Cameron and Major WT Reay (correspondent of Melbourne Herald) got

to the Boer lines, they were blindfolded by a young Boer and a big German. De

la Rey received them with courtesy and took them to the farm Jasfontein were

the grave was. Due to the kindness of the Boer family his grave has been kindly

taken care of over the years. Hales were taken by the Boers to the Volkshospitaal

in Bloemfontein.

http://users.netconnect.com.au/~ianmac/lambie.html).

He was buried on the farm of Hendrik Kotze.

Commander of the Tasmanian Mounted Infantry

Wounded and captured 24 February 1900 at Rietfontein

(1857 - 1941)