BANANACUE

REPUBLIC

Vol I, No. 5

Oct 06, 2004

![]()

by Daphne Cardillo

MASS PSYCHOLOGY/

HISTORY:

On Taking

Sides

THE revolt that took place 18 years ago still brings many people in awe as to why it happened the way it happened, especially those who maintain that political revolts must be tainted with blood -- at least marred by violence. The Enrile and Ramos camps were minimally manned though armed, but since they were separated by a sea of humanity from General Ver's men, no exchange of fires ensued. Our soldiers at last displayed heroism and fair play by not shooting -- with or without President Marcos' orders -- when civilian lives were at stake.

Looking back to that event, it may be a mistake to rationalize so unstructured, unplanned, and unorganized an uprising for worldwide acceptance. That the uprising happened without anyone masterminding it could be history's unraveling of a new phenomenon -- People Power. It could even be God's way of revealing that changes are not perpetrated by individuals but by the collective and that through history, it's the people who should be given credit as heroes and not those self-aggrandizing men who pose as political leaders.

However, there are a few things that can be explained in the EdSA Revolt of which I would like to consider. First is the number of participants that can be deduced through logic. Second is the level of awareness of the people that we can speculate. Third is the atmosphere that prevailed that can be understood in a cultural context.

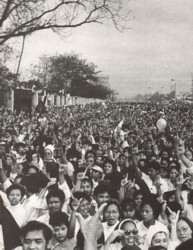

The millions of people that flocked to EdSA was not an unlikely number for a mass assembly at that point in time. In fact, if the country is not an archipelago, more people from the Visayas and Mindanao would have swarmed the streets. That greatest mass action our country ever had was national in character so it took on a national scope.

When Martial Law was lifted in 1981, Section 4 of the Bill of Rights was restored. People started organizing. Student leaders from greater Manila traveled to Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao delivering speeches and urging students in the colleges and universities to restore genuine student government and revive the student paper. But the assembly fever was not confined only among students. It spread along the wide section of the populace; from the political opposition, factory workers, urban poor, farm workers, artists, to the religious.

Suddenly, like a reflex action to Martial Law's repression, mass mobilization became sporadic though less organized and much localized, as they were carried out by interest groups. The succeeding two years saw in the national scene the mushrooming of cause-oriented groups and worker unions, but mass mobilization was still specialized though the participants were increasing in numbers. The gathering of opposition forces while ensuring pluralism followed only in the next two years right after Benigno Aquino Jr.'s assassination. Mass mobilization became multi-sectoral, ecumenical, cross-sectional and non-partisan. The businessmen in Makati even marched to the streets in what we call the "confetti revolution."

The People Power at EdSA was in effect a culmination of a gradual exercise in protest. Since the issue at stake was national in character--the result of the snap election of which Marcos again had won, the people who merely watched rallies and strikes eventually stood up to be counted. So the number rose.

Now for determining the level of awareness

of the participants in that EdSA Revolt, we would need a survey result.

But since no studies were ever made possible, we can only speculate on a

few probabilities. I suppose that about 50 percent of the crowd belonged

to interest groups. These people have a higher level of political

consciousness as a result of joining people's assemblies. Their awareness

of national issues are not limited to the information fed to them by the

press.

For the rest of the flock who stood up to be counted, they could carry with them a variety of individual reasons for joining the crowd. But looking at them as a collective they unconsciously took a side of the issue at hand, that is, they rejected the snap election results. Joining the ranks became a matter of survival.

When the people provided human barricades for Enrile, Ramos and company, they did not do it to save the military leaders. They did it to go against Marcos, to save themselves from his continued rule. For a long time, the Filipino people longed for a leader that would challenge Marcos, but when their only hope in the person of Benigno Aquino Jr was crushed after he was felled by an assassin's bullet, they broke into mass hysteria as evidenced by the protest actions that followed nationwide.

Now here comes Enrile and Ramos, two top Marcos men who represented the much dreaded military establishment openly defying the dictator. As in a flash of wisdom or stupidity, the people openly sided with them. Filipinos are generally bystanders but are natural gamblers and they would be willing to bet on the devil as long as they will be assured of winning. They would even settle for Cory after dismissing the rest of the politicians, as long as Marcos steps out.

We can therefore presume that the Filipino people, even though cowed by fear because of long years of domination, were collectively aware of their sad plight as to openly take power in their hands and topple the greatest ruler they have ever had.

Turning to the most unique characteristic of the EdSA Revolt is like looking ourselves in the mirror and painting the Filipinos at their best. The atmosphere that prevailed in that historical event speaks much of being a "Pinoy"--the hysteria and euphoria mixed with feelings of fear and uncertainty were rolled into an apparent display of heroism, fatalism, religiosity, and humor.

Filipinos avoid direct confrontation if they can help it, and all the characters in that February 1986 drama were trying to refrain from throwing the first stone that would spell commotion. The major players were even civil to each other negotiating a safe way out for the Marcoses.

On the part of the people, they tried to forestall any direct confrontation between the two opposing military forces. No wonder, simple acts of conciliation and mediation pervaded the air, like giving food to the soldiers, singing, praying, cheering, offering flowers, and the like. The atmosphere turned even more festive after the Marcoses fled, prompting Ramos to say "it was like Christmas and New Year and birthdays rolled into one."

In retrospect, the People Power revolt was the finest act of the ordinary citizen in expressing public opinion, for which neither the media nor the insurgents found no match. The people finally made evident their desire to say, No! Tama na! Sobra na! Palitan na!

It was a momentous beginning for taking

sides, and finally, for making a stand.

"We can

therefore presume that the Filipino people, even though cowed by fear

because of long years of domination, were collectively aware

of their sad plight as to openly take power in their hands and topple the

greatest ruler they have ever had."

celebrating the victory on EDSA

Catholic Gandhi-ism

Floral culture: the invention of a

new peace offering