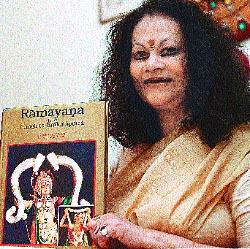

Indira Goswami, who writes under the pen-name Mamoni Raisom Goswami, is a writer in Assamese who has for long been

celebrated - and for all the right reasons. Professor in the Department of Modern Indian Languages and Literature in the University

of Delhi, she has produced long and short fiction of the highest quality, and a truly memorable autobiographical work. The available

English translations of her work do not perhaps reflect the glory of the original. But with Indira Goswami now winning the nation’s

highest literary honour for 2000 - the Jnanpith Award - her work will presumably begin reaching the wider audience that it richly

deserves.

Indira started writing early, as a school-going girl, though her intense and persistent

involvement with the craft began when her husband died in an accident in 1967, only 18

months after her marriage. The pen presumably became her sword to cut a path through

the enveloping gloom. From that day she has ceaselessly used her pen to overcome the

adversities, of which she had more than a fair share in the early part of her life.

Indira was born in 1942, in a traditional Vaishnavite family of Assam which owned a

satra (monastery) and the huge adjoining estate. The satradhikars (heads of the satras)

were held in high esteem by their tenants, who were also disciples. The adhikars were

supposed to be the moral and spiritual mentors of their people. But unbridled power and

excessive wealth brought degeneration in their wake, and from the late 18th century

onwards the moral and spiritual standards of the satras became questionable. Indira was

raised in one such satra, which gave her a vantage point from where to watch the human

drama that was unfolding in this unique social institution of Assam.

Indira has received many other literary prizes including the Sahitya Akademi award in 1982. Among her major novels are Nilkanthi

Broja (1976), Ahiron (1978), Mamore Dhara Tarowal (1980), and Tej Aru Dhulire Dhusarita Pristha (1994) - the last-named

being a novel written with reference to the Delhi riots that followed the assassination of Indira Gandhi in 1984.

Indira’s anthologies of short stories include Chinaki Marom (1962), Kaina (1966) and Hriday Ek Nadir Nam (1990). There is

also the autobiographical piece, Adha Lekha Dastabej (1988).

Indira’s "half-written" autobiography is available in Hindi and English translations. Like most of her writings, it was serialised in a

journal published from Guwahati. Its most striking feature is its utter frankness and courage - which few can match - in laying bare

intimate details of experience. The candour is especially remarkable for a woman publishing in Assamese, and that too in provincial

- rather than a cosmopolitan - cultural environment.

Indira writes in a manner which suggests that her direct experiences of social reality are woven closely into the narrative. This

gives her works a touch of authenticity, even though it carries its hazards for a woman writing in an Indian language. Whenever an

intimate experience is portrayed, there is a natural assumption on the part of the reader that it reflects the writer’s personal

experience - an inference which neglects the creative process that transforms lived experiences into literature.

Being a young and beautiful widow, Indira had to withstand much unwanted attention - the bitter story is narrated in her

autobiography. Her life in Vrindavan during early widowhood is also recorded with great poignancy. Indira had, after becoming a

widow, taken a school-teacher’s job in Goalpara in Assam. But she simply could not stay there, and decided to proceed to

Vrindavan to pursue her research on the Ramayana.

The novel Nilkanthi Broja very powerfully projects the lives of young widows abandoned in Vrindavan by their families. Indira is

probably the first Indian novelist to take up this theme and reveal the cruelty, violence and pathos that surround the lives of these

helpless women. Her Vrindavan experience helps shape the novel, which probably is, along with Daantal Hatir Une Khoa Howdah,

her finest achievement as a novelist.

These Vrindavan widows are mainly from Bengal, and their condition is so wretched that they often face physical abuse from the

pandas who function at the pilgrim town as a mafia. The widows are called "Radheshyami" as they earn their share of food from

temples by chanting "Radha-shyam" all day long in Lord Krishna’s honour. In spite of their pitiable economic condition, these

widows often choose to starve. Whatever meagre money they are able to collect through their mendicant wanderings is deposited

with the panda, to ensure that they are cremated after death. Experience has taught them that unless such an insurance is taken out,

their corpses could well become the food of jackals and dogs. The insurance they purchase is illusory, since the panda, more often

than not, simply pockets the money and disposes of the widow’s body in the Yamuna. Indira describes this sequence of actions in

man’s cruelty to his own species, with typical mastery.

These Vrindavan widows are mainly from Bengal, and their condition is so wretched that they often face physical abuse from the

pandas who function at the pilgrim town as a mafia. The widows are called "Radheshyami" as they earn their share of food from

temples by chanting "Radha-shyam" all day long in Lord Krishna’s honour. In spite of their pitiable economic condition, these

widows often choose to starve. Whatever meagre money they are able to collect through their mendicant wanderings is deposited

with the panda, to ensure that they are cremated after death. Experience has taught them that unless such an insurance is taken out,

their corpses could well become the food of jackals and dogs. The insurance they purchase is illusory, since the panda, more often

than not, simply pockets the money and disposes of the widow’s body in the Yamuna. Indira describes this sequence of actions in

man’s cruelty to his own species, with typical mastery.

Her 1988 novel Daantal Hatir Une Khoa Howdah (English version: The Saga of South Kamrup, or alternatively, The Moth-Eaten

Saddle of the Tusker, 1993) vividly brings out the superstitions, the abuse of power and the deadweight of oppression that widows

had to confront. A part of this novel has been made into a film. The film, Adahya (that which will not be burnt out) was awarded the

Silver Peacock award in the National Film Festival in 1998.

This is probably her best novel, and is considered one of the modern classics of Assamese literature. The locale of South Kamrup

district is exquisitely depicted with its magnificent variety of trees, flowers, creepers, jungles, rivers and mountains, and its

poverty-driven, opium-addicted people in the satra. The entire region comes vividly alive to the reader. Indira’s descriptive power

makes visible what even a local resident may not notice. Her colour metaphors, for example, are excitingly fresh. There is the

"mushroom-coloured" sky, and elsewhere a sky of "muga" silk, which refers to an Assamese handicraft speciality. The sun is

"yellow" now but bears resemblance to a "huge red pumpkin on the field" when it sets. The lips of Indira’s female protagonists

compare in shape and texture with "cut pieces of ripe papaya", and a woman’s skin has the texture of the "bok" flower, which is

found in eastern India and has no commonly-used English equivalent.

There are many possible ways of seeing the narrative of South Kamrup - as the story of widows, as a saga of the ryot-landowner

conflict, as a spectacle of the relationship between man and woman with all the attendant complications of caste and social

hierarchies. Indira powerfully exposes the hypocrisy of Brahmins, their greed and their lop-sided values, and the many

ambivalences of their attitudes towards the rich and the poor, the powerful and the weak.

Indira has also written many exquisite short stories. "The Offspring" (also translated as "The Sun") is one of the very special ones.

The protagonist in this story is Pitambar, a non-Brahmin and a rich merchant. His wife is chronically ill and his chances of ever

having a child by her are rapidly receding. An indigent though grasping priest kindles a hope in Pitambar that Damayanti, a poor but

beautiful Brahmin widow, could bear him a child. He then functions as a go-between frequently extracting pecuniary favour from the

wealthy merchant.

Acute poverty forces Damayanti to submit to Pitambar, following which she becomes pregnant. The priest arranges for their

marriage so that the child (it is assumed that the child will be male) is not born with the stigma of illegitimacy. Pitambar’s dreams ride

high as he awaits the birth of his son. His moment of reckoning comes on a stormy night when he receives the news that Damayanti

has undergone an abortion. It then unfolds that Damayanti had frequently in the past sold her body to maintain her family. But in

every case, she had undergone an abortion in order to retain her caste. The aborted foetus was invariably disposed of in the

bamboo grove of Damayanti’s backyard.

One night Damayanti hears a noise in her bamboo grove and discovers Pitambar digging up the earth to recover and touch the flesh

of the foetus - the scion of his lineage, a part of his own flesh and blood. There is no story in modern Indian literature which quite

describes a comparable yearning for a child to continue the family line. Indira captures this emotion with a dreadful intensity which

touches on the grotesque.

The varieties of violence, all avoidable, that humanity inflicts on itself, whether as group or individual, the pain and the misery they

create, the protection and love which they are either unwilling or unable to provide but which they desperately crave - these are

some of the themes that run through Indira Goswami’s oeuvre. Her graphic depiction of violence and her use of startlingly fresh

images are aspects that make her works unique not only in Assamese but in all of Indian literature. Her autobiography conveys a

sense of the pain, the restlessness and the suffering that she has undergone in various phases of her life. Writing was her way of

overcoming these. With indefatigable energy and incessant effort, she rose above the circumstances that moulded her, but never lost

her profound sense of identification with those who continued to suffer in the river of pain.