Use of Slaves to Build and Capitol and White House 1791-1801: by Bob Arnebeck

| Part

One: Stumbling to a Slave Hire Policy Part Two: Slaves in Skilled Trades |

Part Five

The Use of Slaves as Servants in the City of Washington 1791-1801

The allegories in the painting above were prescient. The power in General Washington's hand runs from the plan of the city spread out on the table through his broad commanding shoulders to the coming generation, and a young hand dominates the globe. Across the table, grandmother and grand daughter cradle the plan as a black house servant looks on. The artist saw through the idea that the new capital would cement the union. Here are Spartan sensibilities showing the city as a nursery for conquerors. The slave stands behind the opulent and chaste pillars of domestic tranquility. Here, he is not a symbol of cheap labor or of any exploitable talent save faithful service. The capital of the so-called Great Experiment in Democracy was not itself to be an experiment in democracy. It would rather serve to showcase the elite of the upstart, soon to be all-conquering, nation. The city was ideally situated to become a training ground for African Americans; where they could have been taught building skills, the use of money, and the exercise of civic responsibility. Instead whites prized slaves as servants.

Of the six men who served as commissioners in charge of readying the public buildings for the reception of the federal government in 1800, only one was not a southern slave owner. William Thornton was raised in the West Indian island of Tortola, then was educated in Britain and became an American in Philadelphia. Soon after his appointment as commissioner, he settled in Georgetown and bought Joseph and Joe from a Georgetown gentleman who attested to their being "honest, sober and free from all bodily complaints." [June 17, 1795 Thornton diary, Library of Congress Manuscript Division]

The three great speculators in city property, all from the north, James Greenleaf, Robert Morris and John Nicholson promptly bought slave servants when they came to the city. Greenleaf bought a slave from Allen Bowie. (Folder 71, Cranch Papers, Cincinnati Historical Soc.,) Morris paid Adam King $350 for 7 years of service by a "mulatto man" named Nat. (Nat wisely ran away after Morris went to debtor's prison.) Nicholson had some repute as a friend of the black race and finessed the problem by hiring a mulatto family to serve him. (November 14, 1796, diary entry in his letterbook Historical Society of Pennsylvania.) He did not own them; he did not separate a family; and they were probably not that black.

Many of the men those speculators sent to oversee their operations in the city, all from the North or Europe, soon found they needed slave servants. The Yankee storekeeper Lewis Deblois hired a mulatto slave servant named Pembroke who judging from the notice seeking his return after he ran away had the makings of a good body servant -- mildly spoken, can shave and dress -- and stole some nice threads.

Thirty Dollars Reward

Ran Away from the subscriber on the 19th inst and indented servant named PEMBROKE (commonly called Harry), a light complexioned Negro the property of Rev. Walter D. Addison, about 5 feet 6 inches high, well made, between 20 and 22 years of age, fair face, pitted with the small pox in his forehead, his ears bored for ear-rings, and is marked on his arm, and is marked on his arm or thigh with a scar from a burn, (is also scar'd on his foot or instep by a cut) mildly spoken, can shave and dress; - had on when he went away a black felt hat, bound with ribbon and took with him a fine claret coloured color short cloth coat, a strip'd nankeen ditto, a light ------- surtout lined with green baize....

Undoubtedly the mores of neighboring Georgetown put pressure on gentlemen in the City of Washington to buy slaves, to the profit of the locals. On January 5, 1796, the merchant Samuel Davidson sold Negro Thomas to the newly appointed commissioner Gustavus Scott, for 112 Pounds 10 Shillings. Davidson bought the slave the week before from Hugh Cox of Charles County, Maryland, for 80 Pounds. Davidson had to buy clothing for the slave, at 2/19/5, and sundries at 3/0/2, and calculated his profit at 26/10/5 or about $70. (Davidson's Account book, Library of Congress Manuscript Division) I don't know if Thomas became a house servant for Scott, but he was not one of the slaves Scott hired out for work at the public buildings. They were named Bob and Kit.

An ad in a newspaper three months later showed how a good servant developed a resume. George Walker offered to sell two slaves, "Aaron an excellent coachman," and Ned whom, he added, he had bought from George Digges, who, most readers would have known, was one of the richest men in Prince George's county. (March 4, 1796 ad) Working from a Georgetown inn, Walker had been one of the first to speculate on city property in 1791. He bought land on the Anacostia River. L'Enfant assured him that area would be developed. Walker moved to the house on his property where he put brickmakers to work and, in 1792, warned "straggly white persons and negroes" away from his orchards (July 7, 1792, ad). That section of the city didn't prosper and Walker sold his land and, since he was moving to Philadelphia and perhaps back to his homeland Scotland, he sold his slave coachman. I don't know who bought Aaron and Ned.

Thomas Law, who brought the fortune he made working for the East India Company to America, married Martha Washington's grand daughter, Eliza Custis (not in the painting above, that is her sister Eleanor), and invested in and developed lots in the city. His young wife was certainly accustomed to slave servants. Evidently Law had other ideas. Judging from a letter to him from Bishop John Carroll he wanted Irish help:

I have seen Healy to day, and agreed with him & his wife to set out wednesday for the city. I have told him generally that your intention is to employ him, as person of trust, to attend to the economy of your house, stables & c & to the workmen, & servants employed about them. I think that he has told me before, that he has acted as butler in some family; but I forgot to ask him today. His wife goes to serve you, as cook, & will, if required, attend likewise to the duties of housekeeper. I believe & hope, that they are a deserving couple, & will give satisfaction. He declined coming upon any terms, before you saw & had some experience of himself and wife. (John Carroll Correspondence, p 163, Dec 18, 1795)

I don't know if Healy was hired and, if so, how long he served the Laws. There is evidence that Law hired a black coachman owned by a Captain Stewart. The Laws separated in 1804. Law recognized and bequeathed money to two bastard sons in his 1832 will. Judging from their names, their mothers, Margaret Jones and Mary Robinson, were probably Irish servants.

The paucity of specific information about servants makes reading between the lines of the records we do have excusable. Before the federal government moved to the city in 1800, the city developed by fits and stops thanks to frequent failures of speculators, shop keepers, and tradesmen. Two anonymous ads placed 14 months may tell a story. A November 25, 1798, ad soliciting a servant read:

WANTED TO HIRE AN orderly, truly female servant, to do the house work in a small family ALSO an active girl or boy to run errands, makes fires, and attend to children. Enquire of the printer.

A January 19, 1798, ad tried to sell a servant:

To Be Sold for want of employment A mulatto woman, a compleat house servant, a person of humane character living in the City, George-town, or their vicinities, would be preferred by her as an owner, and to such a person she would be sold for less than her value, Enquire of the printer

Perhaps the printer of the struggling newspaper placed the ad for himself.

Contractors, carpenters and masons in the city also had slaves as servants. We learned about James Hoban's slave carpenters in Parts One and Two of this essay. He likely had slave servants too. In the July 16, 1796, his long time assistant Clotsworthy Stephenson offered a ten dollar reward for "a complete house servant" whom he had hired out:

Ten Dollars Reward Ran Away from the subscriber, on Saturday the 26th of June, a DARK MULATTO WOMAN named FANNY about 25 years of age, middle sized; she is a complete house servant. When she eloped from Captain C. Myers, where she was hired by the year, she had on a dark chintz dress, and a handkerchief on her head, used as a turban. I believe she has some scars on her neck, occasioned by a whipping some years ago. As she is remarkably artful, no doubt she will change her clothes and pass for a free woman, on a forged pass. She was seen on her way to Bladensburg, and Perhaps to Baltimore....CLOTSWORTHY STEPHENSON

In the summer of 1796 a mason named James Harrigan, perhaps one of the Irish masons who worked with Cornelius McDermott Roe, died and his personal property was sold at auction in Georgetown. Topping the list of possessions were

Two Valuable Negroes,

One a Girl about 16 years old - the other, a Boy about 9; both are accustomed to house work.

Likewise,

Some Wearing Apparel, Mason's Tools, & c.

Only the attributes of the slaves were specified. A mason's clothes and tools were nothing to be particular about. Another Irishman, James Dermot, rose from overseer of the slaves working for the surveyors to head surveyor, replacing Andrew Ellicott, who accused Dermot of moving stakes and changing documents to discredit him. Dermot in turn couldn't weather a storm of accusations that he was inaccurate. He then became what in the future would be called a real estate agent, save, that unlike the modern agent, Dermot sold slaves along with property. In 1800 he advertised that he had two houses to rent, several lots for sale and three Negro girls and a man for sale. (ad dated May 1, 1800). Likely the slaves were offered to provide the domestic help for those who rented those two houses.

Of course, Englishmen who came to the city also needed slave servants. In Part Two I quote the accusations of Irish carpenters that depicted the activities of Thomas Middleton's house slaves. In Part Four I quote the hotel keeper William Tunnicliffe's diary describing the activities of his house slaves.

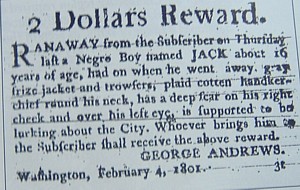

We can assume the Europeans bought slaves when they reached the city. George Andrews came down from Baltimore to plaster the inside walls of the White House. In February 1801 he advertised for the return of "a Negro Boy named Jack about 16 years of age." Was Jack an apprentice who help plaster the White House, or a house slave? Did Andrews bring him down from Baltimore, or buy him in Washington?

Collecting these early references to slave servants is to prelude the obvious. Slave servants might have to outnumber the whites in the biggest house in the city. Mrs. John Adams, the first woman to occupy the President's house, called it a "castle." Most called it the "palace." Oliver Wolcott, the Connecticut born Secretary of the Treasury, wrote to his wife that this palace "cannot be kept in tolerable order without a regiment of servants." When he moved into the palace in October, President Adams noticed that adequate provision had not been made for servants in the house. Back stairs, a "necessary" with three holes, and a "hall" for the servants were needed immediately.

As I noted in Part Three of this essay, Abigail Adams voiced her displeasure, to a correspondent in Massachusetts, at the use of slaves to remove dirt from the White House yard with a cart, so she didn't think of using slaves as servants. Yet given the widely held expectation that Jefferson would win the presidential election, that the President's house would likely become the domicile of slaves had to be obvious to everyone.

Of course, the rich southern planters who moved into the White House could bring slaves from home. How were others to meet the standards set by the President? While Mrs. Adams didn't have black servants, she seemed to have formed a good impressions of the black servants she soon saw in the city. She wrote back to a friend in Massachusetts, "the lower class of whites are a grade below the negroes in point of intelligence and ten below them in point of civility." I quote her letter extensively in Part Three of this essay. In that letter, which she wrote after being in the city a little over a week, she didn't describe any encounters with slave servants. My guess is that she encountered them at the house of her son John Quincy Adams's in-laws who lived in the city. Wolcott also drew a distinction between African Americans and poor whites: "most of the inhabitants [in the city] are low people, whose appearance indicates vice or intemperance, or negroes."

According to the census of 1800, there were 2,464 whites in the City of Washington, 623 slaves, and 123 "Free Negroes." In Georgetown and the rest of the city, i.e. north of Florida Avenue and across the Anacostia, there were counted 3,394 whites, 1,449 slaves and 277 free African Americans. These figures count people of all ages, but, as one of the ads noted above shows, a 9 year old slave could be made "accustomed to house work." By and large, I think that is what white people in Washington proceeded to do. Slaves were not trained to be skilled workers. Whites longed for African Americans, slave and free, to be good servants.

I do not have the evidence to prove this. My research centered on building the Capitol and White House. Work stopped on both buildings in 1801 even though both the Capitol and White House were unfinished. The chaotic state of the city obscured the transition from a premium put on slaves as common laborers to their being sought as house servants. The first Congress to sit in the city had a short term that would end, by law, on March 3, 1801. So few congressmen made efforts to establish themselves in the city. The House had to meet in a room above the Senate chamber. There was not much room to spare in either place. No offices were provided for congressmen; there was scarcely enough housing for congressmen; they shared bedrooms and messed around large tables. There was not much room for their personal servants. However, with each succeeding year the city afforded more facilities for these upper class men to claim their prerogatives.

The challenge is to trace the rise of the servant class in the city. Unfortunately, like a slave, a servant is known primarily, if not only, by his or her first name. From the census roles one can make a list of the names of some of the 400 free blacks who lived in the District of Columbia north of the Potomac. The list seems to show the African American struggle for identity:

Joseph Adams, Lydia Adams, Mary Adams, Agray, Grace Almonds, Amey, David Astin, John Bateman, Clement Boone, Jenny Broone, Charles Brown, Asrah Butler, Free Butler, Mechy Butler, Nathros Butler, Nelly Butler, Ralph Butler, Lucy Butter, Wm Caton, Free Caty, Mary Chubb, Nancy Coats, Henry Day, Bethany Demsy, Wm Dicks, Obed Diner, Wm Fields, Peggy Flannel, Free Nancy, Rich Freeman, Solomon Green, Nathan Gross, Peter Hackett, Rich Hall, Free Hannah, Letchy Hill, Stephen Hill, Josy Holland (7), Pheby Holly, Rubin Holy, Joseph Holmes, John Hutton, Sarh Mason, Paul Moon, Nelly, Cathrine Niginis, Robt Pade, Patrenias, George Pirate, Liverpool Pooley, Nancy Prout, Nancy Quanders, Free Rachel, Betsy Rawlings, John Rawlings, David Read, Jacob Riggs, Thomas Robertson, Hezekiah Rounds, Benj Rounds, Basil Russell, Scelin, Rachel Shorter, Fanny Smith, James Sprigg, Eliz. Taylor, Gusties Thomas, John Thompson, Tow Tony, Sally Turner, Peggy Veach. Benj Wheeler, Fran Williams, Yarrow, Cloe Young

Of the 75 people named, six only have one name, and five are named Free, as in "Free Butler." Still, most of the names seem as respectable as the names of white people. Yet, white people in 1800 rarely mentioned the names of free blacks in their letters, and generally referred to all blacks with their first names. So it is difficult to identify servants in that list of 75.

Also obscuring the issue is that whites simply did not want to notice blacks, and did so only in passing and dismissively. Secretary of the Treasury Oliver Wolcott wrote a long letter to his wife on the Fourth of July 1800 describing the new capital city, and in it he gives a very sketchy look at where I think free Africans Americans began to live. Wolcott's Memoir of the Administration of John Adams can be read on Google Books. Below are jpeg images of the letter to his wife:

Wolcott's impression of the black community in Washington is not flattering:

Greenleaf's point presents the appearance of a considerable town that has been destroyed by some unusual calamity. There are fifty or sixty spacious houses, five or six of which are inhabited by negroes and vagrants, and a few more by decent looking people; but there are no fences, gardens, nor the least appearance of business.

In the primary documents about the city dating from 1792 to 1799, the word "Negro" is synonymous with slave. In 1800, with the influx of northerners there seemed to be no distinction between slaves and free blacks. I assume that the blacks living with the vagrants on Greenleaf's Point were free. (Wolcott wrote when workers were readying the public buildings for occupancy and preparing the grounds, including building a drainage ditch not far from the Treasury building beside the President's house. Mrs. Adams noticed the race of the workers clearing rubbish out of her yard, Treasury secretary Wolcott didn't.)

There were also areas where slaves lived. In that year, 1800, those who invested in the city expected streets to be opened and public squares to be cleared of temporary buildings. The plan of the new city was at last to eclipse the reality of the old plantation fields and woods. James Barry, a merchant from Baltimore, had been lured by Thomas Law to invest in the city. He wanted to build a store and make other improvements but was appalled that the mother of the original proprietor of the land, Daniel Carroll of Duddington, still lived illegally on public property surrounded by slaves and other dependents. Barry wrote to the commissioners:

by your letter of the 31 ult I was satisfied that the subject regarding the removal of old brick sheds habited by Mrs. Fenwick & citizens black and I suppose of colour, was to be taken up and discussed and decided yesterday.... Can it be expected situated as I am, surrd by shades of all colors, that I am to break ground by placing a building or improvements within 30 or 40 feet of the hovels & purloins of this class? (Commissioners' letters received)

Unfortunately, it is impossible to get any sense of what happened to these groups of slaves and free blacks. Notley Young, who in 1790 owned most of the land that became southwest Washington, owned 271 slaves in 1790 but only 70 in 1800. But while he was divesting himself of chattels, newcomers were acquiring them. John Templeman who came to the city from Boston owned 25 slaves in 1800, most probably employed in his shipping business.

It is very difficult to trace slaves from owner to owner. Whites often noted when they got black servants, but not where they come from, except in the ads they placed if the slave ran away. The young editor Samuel Harrison Smith was encouraged to move from Philadelphia to Washington by Thomas Jefferson and start a pro-Jefferson newspaper, the National Intelligencer. He came with his wife Margaret Bayard Smith who was a prolific letter writer, and in time, magazine writer and novelist. Both Samuel and Margaret were born in Pennsylvania. Within a few months of their arrival, they began to adjust to Southern way. Margaret wrote to her sister:

...I have changed my servants & instead of two white women, I have now an old black man & his wife to whom I pay the same wages as I did the women. Betsy is still with me, & I continue well pleased with her; she is active & intelligent; but she is proud and irritable. I always determined to have good servants, thinking that in most cases a mistress might make them what she pleased, & I am still of that opinion. I think I shall put my determination into effect. You see Mary I possess two of the most essential ingredients of domestic felicity, a good husband & faithful servants.... (Margaret Bayard Smith to Mary Ann Smith 12/22/00, Library of Congress Manuscript Division)

She doesn't really say who the old black man and his wife are, nor is she clear about their status. It is likely the "old black man & his wife" were free, but not necessarily because by 1800 it was not uncommon for slaves to hire themselves out by the month evidently having made their own arrangements with their masters.

The Smiths soon bought a rural retreat near today's Catholic University and hired slaves to work there. When the master of one of the hired slaves died, the slave, Jessy, who struck the Smiths as "a fine, good natured, active young man," asked the Smiths to buy him. Mrs. Smith wrote that her husband "would not sacrifice his principles which were all adverse to slavery." (Such scruples did not prevent Smith from having an ad for a runaway slave in the first edition of the National Intelligencer offering a $40 reward for Nace, "aged Thirty years, about five feet high, light complexion, wears his hair queued, a well set truncky fellow," who his master, Zachariah Sothoron of Charles County, suspected was in the City of Washington.)

Another man bought Jessy but he twice ran away coming to the Smith farm. The Smiths decided to buy him with a promise to assuage their guilt. They would give him his freedom when he reached 35, if he behaved well. Jessy's new master feigned negotiations with the Smiths but when he got his hands on Jessy led him away in chains. In her diary Mrs. Smith recalled how she remonstrated with the villain. If Jessy was taken and could not escape he would kill himself just as two weeks before a slave being transported across the Potomac to jail had jumped off the boat while in chains and drowned himself. She recalled an old woman who had hung herself when her son was sold, then he escaped and threw himself into the Potomac. The slave's owner only smiled, then explained, "I mean to sell him directly to the Georgia negro-buyers and then he may blow his brains out and hang himself as soon as he pleases." And he dragged the slave away.

Twenty years later Smith wrote, A Winter in Washington, a novel about life in Washington during the Jefferson administration. The tragic stories of Jessy and other slaves were not in the novel. Instead the slaves in the novel are faceless servants. Designed to be a morality tale for young women, the heroine Mrs. Seymour regularly took her daughter to do charity work among the poor. They visited a miserable white woman, Jenny, who lived in a shack in the southwest section of the city with a black man. She had had a child out of wedlock and was banished by her family. The black man who had worked as a servant in a white family, earning $10 a month, took pity on her and married her. They had five mulatto children and he struggled to maintain her as a well as he could. Smith does represent the black man as caring and considerate, which only to highlighted the misery of the white woman who bitterly hated all whites. Even a good black man could not redeem her from a life of misery because she crossed the color line. Mrs. Seymour offers to at least help the children:

"But why do you not put them out to service?" "Put them out to service!" exclaimed Jenny, turning her head, and glaring her angry eyes on them; "put them out to service, indeed! do you suppose they are slaves?"

"They might better be slaves, than be kept at home to starve," said Mrs. Seymour.

"They had better be in their graves," muttered the woman.

"Fie, fie, Jenny, to the like o' that; but they shan't starve while this old arm can saw a stick of wood." (p 282)

Mrs. Seymour's daughter concludes:

There is something so disgusting, so revolting, in the idea of her having married a black man, that it totally destroyed every feeling of compassion; it is the first time in my life I ever heard of such a connexion. It is because Jenny is sensible of the irremediable disgrace and degradation of her situation, that she is so jealous and vindictive. Poor wretch! (p 284)

There is a growing literature on Margaret Bayard Smith and her writing, all of which I have not read, and there is a discussion of her attitude to race relations. But it seems clear that no matter her discomfort with slavery, she saw African Americans primarily as servants and was confident that white people could mold them: I always determined to have good servants, thinking that in most cases a mistress might make them what she pleased.

The wife of another prominent man gives us a better look at the servant problem in Washington. On July 31, 1800, Mrs. William Thornton wrote in her diary: (Records of the Columbia Historical Society, vol. 10)

Three young negro women came - I engaged one of them to come here on Monday - they came from Marlbro [Prince George's County, Maryland]- to hire here.

Evidently as a city grew, the formal process of slave hire changed. It was no longer a question of masters sending slaves to an unbuilt city where the commissioners arranged for them to be housed and fed, and for wages to be sent to the masters. Slaves went from door to door looking for work.

In 1800 Mrs. Thornton kept a daily diary in which she primarily recorded her extensive entertaining of the many people coming to the city, to inspect it early in the year, or to find accommodations as the federal government established itself in the city. Her diary is the only source I have come across that shows how whites tried to get slave servants.

Mrs. Thornton was the wife of Commissioner William Thornton. The Thorntons lived with her mother, but had no children of their own. However, there were children in the house. Mrs. Thornton was never explicit about these domestic arrangements, but from the diary we can glean that they kept two children of a Dutch housekeeper who worked with them for three years and then married and moved in with a carpenter in the city. The children, William and Betsy, were "indented" to the Thorntons, i.e. indentured servants. They also bought a slave, Daniel, his wife, Lucy, and infant, Bet. The man, Daniel, worked at their farm outside the city. The wife staying in the city but was deemed an incompetent servant. The baby first stayed in the city with "its" mother, and then was sent out to the farm with "its" father. Mrs. Thornton never betrayed an emotional attachment with these people, indented or slaves, in her diary.

As her February 18 diary entry reveals, managing servants can be difficult:

Could not go to George Town as our Servant Woman went home on Saturday & is not returned, & the woman [Lucy] that came yesterday knows nothing... Mr. Wallace came for the years wages (36$) due for the mulatto woman Iris - which I paid.

But the diary makes clear that the Thorntons quite relied on their slave servant Joe, who had the same name as one of the two slaves they bought when they came to the city in 1795. He frequently traveled alone from the city house to the Thornton farm in the countryside, and seemed to manage the horses, both for the carriage, and on the stud farm. Thornton prided himself on being a horse breeder. For help on the farm, Thornton hired slaves. On January 16, Mrs. Thornton noted: "Hired a Negro Lad of him [Mr. Digges] named Nic @ L18 per annum beside cloathing." That was a traditional yearly hire, but he also hired slaves by the month, not always with good results. On August 30, Mrs. Thornton wrote: "Dr. T found that it was the hired Negroes that stole the cabbage -- they both went off."

There is no mention in the diary of Thornton seeking justice or retribution. Mrs. Thornton was laconic about alarming activities by slaves. She wrote on September 8:

Maj Gibbons gave us an account of the attempt to set Mrs. Johnson's house on fire & we heard that the Negro fellow who is suspected, slept in our house the night it happened (Sunday) while we were at the farm

This Mrs. Johnson may have been John Quincy Adams's mother-in-law, and if so, it becomes curious why Mrs. Adams, the First Lady, might have gotten a good impression of African Americans from them. I should add that I don't recall reading any letters or diary entries written at this time in Washington, that mention the slave rebellion in Richmond in the late summer of that year. I think this reflects the confusion of race relations in the city caused by the confused living arrangements in the city that was spread out into disparate communities over several thousand acres of land. The need for black servants was so acute that the white elite were loath to entertain any doubts as to their loyalty.

The Thorntons lived near the White House and commonly walked to that building and the Tayloe mansion below it. They owned the lot across from the mansion. (Thornton is credited with designing the building but I don't think he did. Only once in her diary that year as the building was rising did Mrs. Thornton mentioned that the builder William Lovering visited Thornton. All the diary entries mentioning John Tayloe pertain to horses nor houses.) To go to Georgetown, the Capitol, or Greenleaf's Point, they needed to go by carriage. That meant Joe had to take her and often her mother in a carriage. Messages were passed from family to family by servants. The servants were, of course, unnamed, often called "boy." On April 24, Mrs. Thornton wrote: "Heard from one of Mrs. Burnes's Negroes that she was not at home," which saved Mrs. Thornton some steps because Mrs. Burnes lived below the Tayloe house and was just outside her walking range.

While these house slaves were largely ignored and anonymous, whites knew who owned them, and knew, and sought to know, more about the slaves in the community. Throughout the year 1800 the Thorntons looked for slaves to buy: men, for the farm or to assist Joe who judging from the diary seemed just able to perform all the tasks the Thorntons assigned (finding runaway horses seemed the most time consuming,) and women as house servants. They seemed unlucky with the men. On May 12 the Thorntons went to Marlborough, the county seat of Prince George's County, Maryland, some 15 miles away. She wrote:

we wished to purchase a Negro boy was one of the reasons our taking this trip...went to two or three shops - found them badly supplied the best belonged to a free negro man. Dr T purchased a negoro man for 400 $

This complement of the free black store keeper is the only kind thing she said about African Americans in her diary. So they came to buy a boy, and wound up with a man slave. While Dr. Thornton didn't practice medicine, he had a medical degree from Edinburgh University, the premiere medical school in the English speaking world. He soon discovered a flaw in his purchase.

[May] 15th Dr T wrote to the Gentlemanen who had the direction of the Sale near Marlboro that he could not take the Man (who came yesterday) as he is not in health (having a rupture)

This diary entry is interesting in two other respects. The purchase on the 12th was not cash and carry. The slave did not arrive at the Thorntons' door until the 14th, evidently alone, because there was no one on hand to join the doctor as he inspected his new acquisition. A diary entry twelve days later is also interesting.

27 when we came home found John, the Man purchased at the Sale returned - he said his owners accused him of having informed respecting his disease, and that he was wandering & had no home. Dr T discharged him before Mr. Forrest & gave him a few lines mentioning the circumstance as they really were

No one wanted the slave! The diary doesn't say what happened to John, nor if Thornton lost any money on the deal. One assumes he purchased him with a note that he refused to honor. Rather than continue to feed a slave who was now notoriously known as unfit, the "owners" [note the plural] simply let him go.

In the midst of this, the Thorntons pressed to find a good slave, as her diary entry for May 21 indicates:

Just as we were going to dinner Col Sims of Bladensburg was passing by. Dr T asked him in to enquire about a Negro of his which he understood was for sale - he gave him a high Character but said he did not wish to sell him

Shopping for slaves did not merely involved checking ads in the newspaper, there were not that many, or going to slave auctions, not many of those either. One had to be on a look out. On October 18, Mrs. Thornton wrote that she "called to enquire of Mrs. Wm. King the character of a woman who is to be sold." At few weeks later, November 10, she wrote: "a boy came here to hire as a Waiter, he asked $9 pr Month." She didn't say if she hired him at what appears to be a high wage.

Mrs. Thornton's diary can give the impression that she was victimized by the caprices of slaves, but two letters written the same year by Samuel Davidson suggest that whites had not lost the knack of victimizing blacks. On October 16 Samuel Davidson wrote to Gen. John Swan in Baltimore: "I hinted to John, that if he served you faithfully for fifteen years, that you would give him his freedom; the poor fellow jumped at that idea, and made me every promise. I give you this hint for your government." Evidently Swan was not entirely pleased with John, because on November 8 Davidson advised him "that a little hickory oil, early and judiciously applied to him, will rectify that evil and render him a very valuable slave." (Davidson letterbook Library of Congress)

As I noted in Part One of this essay slave hire was traditionally arranged in December and January. This seemed to become a popular time for slave sales too. I find the juxtapositions in parts of the two diary entries below telling. On the same day news came of Jefferson's election, Thornton set off to buy one of Mrs. Burnes's slave. She was the widow of the proprietor who owned the land on which the White House was built. Then on another day, Thornton went beyond the Capitol, dropping off something there for Robert E. Lee's father, to look for slaves to buy. Meanwhile, back home, slaves for sale were brought to his door. Careful research convinced him not to buy:

[December] 12 Dr T sent Joe to town on business - A terrible stormy Day - Accounts received that Mr. Jefferson is chosen President - the Votes in S Carolina determined it. Dr T walked to Mrs Burns where there was to have been a sale of Negroes, but it was cancelled.... 15 Dr T went to the Capitol to take his letters to Genl Lee - thence to a sale of Negroes over the Eastern Branch.... A man came with a woman and child for sale... Mr. Forrest walked with us to a woman's of the name of Ray to enquire of the Character of the negro woman, as we retruned we met the man who had the selling of her, and told him we did not want her - Mrs. Ray did not speak well of her.

There is another interesting entry two days later. The indifatigable Joe was once again collecting what one of the Thornton's runaway horse left behind. He ran into a sharp mistress who looked out for the rights of her slave:

17 Joe out all the morning seeking the saddle & bridge - Found it, but the Woman wou'd not let him have it, 'till we sent a half a dollar for her negro man's taking, when if he had let it alone the mare wou'd have brought it with her.

The final entry in her diary mentioning slaves suggests how valuable it would have been to us if she had continued her diary in such detail, sketchy though it could be about race relations.

20 Bought a wooden tray of a Negro Man, who has purchesed his freedom by making them & bowls at his leisure time.

Here is a hope for a brighter future, save that despite buying his freedom, the man was still called a "Negro" which was synonomous with slave.

Meanwhile there was worked done on the Thornton's house, which they rented, and also on the neighboring lot. There was considerable building throughout the city. On August 24 a Mr. Brent called, perhaps the Robert Brent President Jefferson would soon appoint as the city's first mayor, with a list of current building: "Mr. Brent showed us a list of houses building at this time 68 of brick and numberless wooden ones." Unfortunately, Mrs. Thornton rarely revealed the race of the men doing all this work. John Templeman, who owned 25 slaves, owned the neighboring lot and had a cellar dug. Likely his slaves did the digging, but Mrs. Thornton only describes them as men. Hugh Densley who whitewashed the White House sent men to whitewash the Thorntons' rooms and they did a terrible job. She only calls the first crew and the second sent to redo the work "men." After a great storm flooded their rooms, she hired men to clean up but did not specify their race: "[August 9] sent and got four men to bail the water out of the kitchen."

In April the Thorntons sought help to prepare their gardens. In this case she was particular about race:

April 7 Hired an old Negro Man (little Joe's father) to work in the Garden &c for a month @ $6 April 8 hired an Irishman for a month @ $12 to plant Trees, ditch & work in the Garden

April 16 Got a Negro Man to dig the Holes [for the trees]

I don't think the imprecision about the race of the workers in the city means that they were all black. As noted in other parts of this essay, a large number of white workers came to the city at this time attracted by all the work to be done. It is possible that the crews doing the work included both white and black workers, and that Mrs. Thornton found it distasteful to particularize that. She certainly identified whites as Irishman, as in the case of the gardener above. Dr. Thornton who supervised construction of the public buildings disliked talking with common workmen. It is likely Mrs. Thornton took no pleasure in it. By not talking to them she could avoid identifying the men who whitewashed her rooms so poorly as Irishmen, which they probably were.

As so often happens when writing history, just when one digs into another seam of interesting material, time runs out. When I researched my book about preparing the city for the reception of the federal government I ended in the spring of 1801. So I am not qualified to carry on this discussion about the use of slaves as servants. Mrs. Thornton's diary points a researcher in one interesting direction. How did the prominent men and families coming to the city handle the servant problem?

William Thornton tried to arrange accommodations for Secretary of State John Marshall, even offering to allow him to sleep in the White House when he first came to the city in the summer of 1800. Marshall declined and stayed at Tunnicliffe's hotel. Thornton then offered to share his own house with Marshall. In her October 25 diary entry, Mrs. Thornton wrote: "Genl Marshal came while we were at breakfast to speak on the subject of his lodging with us but concluded to take a house, as he thought his family of servants wou'd make it disagreeable to us."

Evidently, it was not simply a case of every house having servants, but every man having servants. However, Mrs. Thornton's diary does reveal instances when servants were shared, or at least offered. When Mrs. Peters had trouble with her coachmen, Mrs. Thornton offered to send her Joe to serve them. As congressmen and other government officials came to the city in October for the opening of Congress, the Thorntons seemed be constantly entertaining visitors. Perhaps for that reason, on October 27, they sent the child of the slave Lucy out to the farm to be with its father. Perhaps they needed her undivided attention on their guests, not her child. On that same day one of their horses ran away which meant that their servant Joe had to go out and find it. Mrs. Thornton wrote in her diary: "I was obliged to borrow a servant (Jerry) Joe having gone again after the horses."

The Jerry she borrowed may have been Jeremiah Holland who, we know from the commissioners' records in the National Archives, was at that time the commissioners' servant. From the payrolls in the Archives we can just trace the career of this free African American from a laborer working with the surveyors, then as a laborer at the Capitol and then as the commissioners' servant. I am not sure how much he was paid as a servant for the commissioners, but presumably the same as any slave laborer, which was the case when he worked with the surveyors and at the Capitol. He was not allowed to better himself, despite being singled out in January 1795 as one laborer on the surveyors' crew who deserved more pay. His supervisor attached a note to the monthly payroll:

Pay Jerry the black man a rate of $8 per month for his last months services; he is justly entitled to the highest wages that is due to our hands - being promised it and the best hand in the department.

Jerry Holland did get some benefits from his ability. In winter months when fewer monthly hires were on the payroll because there was less work to be done, he was kept on the job. And being the commissioners' servant got him out of back breaking work altogether. And he may have been allowed to live in a house without other laborers. A note in the commissioners' records mentions a chimney was to be provided for Holland (April 2, 1800 Commissioners Proceedings). But there is no evidence that he was ever paid $96 a year, as he was promised in January 1795. No laborer, slave or free, was ever paid that much. And even though his skills were evident in 1795, he was evidently never trained for any skilled position. He always signed for his pay by marking an X. Perhaps if he had been taught to write, he could not only have been the commissioners' servant, but he could have assisted their clerk.

We do well to call attention to those slaves who did exhibit skills, but we cannot let our celebration of those skills obscure the fact that slaves were not encouraged to develop any skills beyond that of a servant, either attending the masons or attending the commissioners. It is perhaps unfortunate that we cannot credit African Americans with as large a role in building the Capitol and White House as we, both white and black, might wish. But at least we are not left with the question of what happened to the skilled slaves who we wish did contribute. The shortsighted racism of white Americans denied them their chance and this brief decade of opportunity for both races passed only to prove the continuity of that racism.

Bob Arnebeck