Grouping Menu

Page Menu

| Free Genealogy Resources Online | |

Jewish History

Jewish history is the

history

of the Jewish

people, faith (Judaism)

and culture. Since Jewish history encompasses four thousand years and

hundreds of different populations, any treatment can only be provided in

broad strokes. Additional information can be found in the main articles

listed below, and in the specific

country histories listed in this article. Ancient Jewish History (through 50 CE) Ancient Israelites

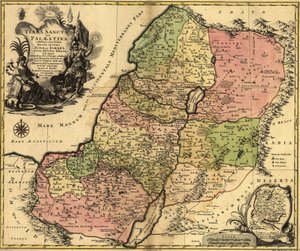

1759 map of the tribal allotments of Israel

For the first two periods the history of the Jews is mainly that of Fertile Crescent. It begins among those peoples which occupied the area lying between the Nile river on the one side and the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers on the other. Surrounded by ancient seats of culture in Egypt and Babylonia, by the deserts of Arabia, and by the highlands of Asia Minor, the land of Canaan (later known as Israel, then at various times Judah, Coele-Syria, Judea, Palestine, the Levant, and finally Israel again) was a meeting place of civilizations. The land was traversed by old-established trade routes and possessed important harbors on the Gulf of Akaba and on the Mediterranean coast, the latter exposing it to the influence of other cultures of the Fertile Crescent. Traditionally Jews around the world claim descendance mostly from the ancient Israelites (also known as Hebrews), who settled in the land of Israel. The Israelites traced their common lineage to the biblical patriarch Abraham through Isaac and Jacob. Jewish tradition holds that the Israelites were the descendants of Jacob's twelve sons (one of which was named Judah), who settled in Egypt. Their direct descendants respectively divided into twelve tribes, who were enslaved under the rule of an Egyptian pharaoh, often identified as Ramses II. In the Jewish faith, the emigration of the Israelites from Egypt to Canaan (the Exodus), led by the prophet Moses, marks the formation of the Israelites as a people. Jewish tradition has it that after forty years of wandering in the desert, the Israelites arrived to Canaan and conquered it under the command of Joshua, dividing the land among the twelve tribes. For a period of time, the united twelve tribes were led by a series of rulers known as Judges. After this period, a Israelite monarchy was established under Saul, and continued under King David and Solomon. King David conquered Jerusalem (first a Canaanite, then a Jebusite town) and made it his capital. After Solomon's reign the nation split into two kingdoms, Israel, consisting of ten of the tribes (in the north), and Judah, consisting of the tribes of Judah and Benjamin (in the south). Israel was conquered by the Assyrian ruler Shalmaneser V in the 8th century BCE. There is no commonly accepted historical record of those ten tribes, which are sometimes referred to as the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel. Exilic and Post-Exilic PeriodsThe kingdom of Judah was conquered by a Babylonian army in the early 6th century BCE. The Judahite elite was exiled to Babylon, but later at least a part of them returned to their homeland, led by prophets Ezra and Nehemiah, after the subsequent conquest of Babylonia by the Persians. Zoroastrianism was the state religion of the Persian Empire. The extent to which Zoroastrianism has been an influence in the development of Judaism is a subject of some debate among scholars (See Christianity and world religions#Possible relationship with Zoroastrianism through Judaism). Already at this point the extreme fragmentation among the Israelites was apparent, with the formation of political-religious factions, the most important of which would later be called Sadduccees and Pharisees. The Hasmonean KingdomAfter the Persians were defeated by Alexander the Great, his demise, and the division of Alexander's empire among his generals, the Seleucid Kingdom was formed. A deterioration of relations between hellenized Jews and religious Jews led the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes to impose decrees banning certain Jewish religious rites and traditions. Consequently, the orthodox Jews revolted under the leadership of the Hasmonean family, (also known as the Maccabees). This revolt eventually led to the formation of an independent Jewish kingdom, known as the Hasmonaean Dynasty, which lasted from 165 BCE to 63 BCE. The Hasmonean Dynasty eventually disintegrated as a result of civil war between the sons of Salome Alexandra, Hyrcanus II and Aristobulus II. The people, who did not want to be governed by a king but by theocratic clergy, made appeals in this spirit to the Roman authorities. A Roman campaign of conquest and annexation, led by Pompey, soon followed. Judea under Roman rule was at first an independent Jewish kingdom, but gradually the rule over Judea became less and less Jewish, until it became under the direct rule of Roman administration (and renamed the province of Judaea), which was often callous and brutal in its treatment of its Judean subjects. In 66 CE, Judeans began to revolt against the Roman rulers of Judea. The revolt was defeated by the Roman emperors Vespasian and Titus Flavius. The Romans destroyed much of the Temple in Jerusalem and, according to some accounts, stole artifacts from the temple, such as the Menorah. Judeans continued to live in their land in significant numbers, and were allowed to practice their religion, until the 2nd century when Julius Severus ravaged Judea while putting down the bar Kokhba revolt. After 135, Jews were not allowed to enter the city of Jerusalem, although this ban must have been at least partially lifted, since at the destruction of the rebuilt city by the Persians in the 7th century, Jews are said to have lived there.

The diaspora

Many of the Judaean Jews were sold into slavery while others became citizens of other parts of the Roman Empire. This is the traditional explanation to the diaspora. However, a majority of the Jews in Antiquity were most likely descendants of convertites in the cities of the Hellenistic-Roman world, especially in Alexandria and Asia Minor, and were only affected by the diaspora in its spiritual sense, as the sense of loss and homelessness which became a cornerstone of the Jewish creed, much supported by persecutions in various parts of the world. The policy of conversion, which spread the Jewish religion throughout the Hellenistic civilization, seems to have ended with the wars against the Romans and the following reconstruction of Jewish values for the post-Temple era. Of critical importance to the reshaping of Jewish tradition from the Temple-based religion it was to the traditions of the Diaspora was the development of the interpretations of the Torah found in the Mishnah and Talmud.

Jews in the Middle Ages (50 CE through 1700 CE)The experience of Jews varied from country to country and region to region. See the main articles Jews in the Middle Ages in Europe and the History of Jews in Arab lands.

EuropeJews settled throughout Europe, especially in the area of the former Roman Empire. There are records of Jewish communities in France (see History of the Jews in France) and Germany (see History of the Jews in Germany) from the 4th century, and substantial Jewish communities in Spain even earlier. By and large, Jews were heavily persecuted in Christian Europe. Since they were the only people allowed to loan money for interest (forbidden to Catholics by the church), some Jews became prominent moneylenders. Christian rulers gradually saw the advantage of having a class of men like the Jews who could supply capital for their use without being liable to excommunication, and the money trade of western Europe by this means fell into the hands of the Jews. However, in almost every instance where large amounts were acquired by Jews through banking transactions the property thus acquired fell either during their life or upon their death into the hands of the king. Jews thus became imperial "servi cameræ," the property of the King, who might present them and their possessions to princes or cities. Jews were frequently massacred and exiled from various European, countries. The persecution hit its first peak during the Crusades. In the First Crusade (1096) flourishing communities on the Rhine and the Danube were utterly destroyed; see German Crusade, 1096. In the Second Crusade (1147) the Jews in France were subject to frequent massacres. The Jews were also subjected to attacks by the Shepherds' Crusades of 1251 and 1320. The Crusades were followed by explusions, including in, 1290, the banishing of all English Jews; in 1396, 100,000 Jews were expelled from France; and, in 1421 thousands were expelled from Austria. Many of the expelled Jews fled to Poland. The worst of the expulsions occurred following the reconquest of Muslim Spain, which was followed by Spanish Inquisition in 1492, when the entire Spanish population of around 200,000 Sephardic Jews were expelled. This was followed by expulsions in 1493 in Sicily (37,000 Jews) and Portugal in 1496. The expelled Spanish Jews fled mainly to the Ottoman Empire, Holland, and North Africa, others migrating to Southern Europe and the Middle East. In the 16th century, almost no Jews lived in Western Europe. The relatively tolerant Poland had the largest Jewish population in Europe, but the calm situation for the Jews there ended when Polish and Lithuanian Jews were slaughtered in the hundreds of thousands by the Cossack Chmielnicki (1648) and by the Swedish wars (1655). Driven by these and other persecutions, Jews moved back to Western Europe in the 17th century. The last ban on Jews, that of England, was revoked in 1654, but periodic expulsions from individual cities still occurred, and Jews were often restricted from land ownership, or forced to live in ghettos.

Spain, North Africa, and the Middle EastDuring the Middle Ages, Jews were generally better treated by Islamic rulers than Christian ones. Despite second-class citizenship, Jews played prominent roles in Muslim courts, and experienced a "Golden Age" in the Moorish Spain about 900-1100, though the situation deteriorated after that time. History of Jewish communities indigenous to the Middle East and North Africa is described in the article Mizrahi Jew.

The European Enlightenment and Haskalah (1700-1800s)During the period of the European Renaissance and Enlightenment, significant changes were happening within the Jewish community. The Haskalah movement paralleled the wider Enlightenment, as Jews began in the 1700s to campaign for emancipation from restrictive laws and integration into the wider European society. Secular and scientific education was added to the traditional religious instruction received by students, and interest in a national Jewish identity, including a revival in the study of Jewish history and Hebrew, started to grow. Haskalah gave birth to the Reform and Conservative movements and planted the seeds of Zionism while at the same time encouraging cultural assimilation into the countries in which Jews resided. At around the same time another movement was born, one preaching almost the opposite of Haskalah, Hasidic Judaism. Hasidic Judiasm began in the 1700s by Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov, and quickly gained a following with its more exubarent, mystical approach to religion. These two movements, and the traditional orthodox approach to Judiasm from which they spring, formed the basis for the modern divisions within Jewish observance. At the same time, the outside world was changing, and debates began over the potential emancipation of the Jews (granting them equal rights). The first country to do so was France, during the Revolution in 1789. Even so, Jews were expected to integrate, not continue their traditions. This ambivalence is demonstrated in the famous speech of Clermont-Tonnerre before the National Assembly in 1789:

1800sThough persecution still existed, emanicipation spread throughout Europe in the 1800s. Napoleon invited Jews to leave the Jewish ghettos in Europe and seek refuge in the newly created tolerant political regimes that offered equality under Napoleonic Law (see Napoleon and the Jews). By 1871, with Germany’s emancipation of Jews, every European country except Russia had emancipated its Jews. Despite increasing integration of the Jews with secular society, a new form of anti-Semitism emerged, based on the ideas of race and nationhood rather than the religious hatred of the Middle Ages. This form of anti-Semitism held that Jews were a separate and inferior race from the Aryan people of Western Europe, and led to the emergence of political parties in France, Germany, and Austria-Hungary that campaigned on a platform of rolling back emancipation. This form of anti-Semitism emerged frequently in European culture, most famously in the Dreyfus Trial in France. These persecutions, along with state-sponsored pogroms in Russia in the late 1800s, led a number of Jews to believe that they would only be safe in their own nation. See Theodor Herzl and Zionism. At the same time, Jewish migration to the United States (see Jews in the United States) created a new community in large part freed of the restrictions of Europe. Over 2 million Jews arrived in the United States between 1890 and 1924, most from Russia and Eastern Europe.

1900sThough Jews became increasingly integrated in Europe, fighting for their home countries in World War I and playing important roles in culture and art during the 20s and 30s, racial anti-Semitism remained. It reached its most virulent form in the killing of approximately six million Jews during the Holocaust, almost completely obliterating the two-thousand year history of the Jews in Europe. In 1948, the Jewish state of Israel was founded, creating the first Jewish nation since the Roman destruction of Jerusalem. Subsequent wars between Israel and its Arab neighbors, and the flight in the face of persecution of almost all of the 900,000 Jews previously living in Arab countries. Today, the largest Jewish communities are in the United States and Israel, with major communities in France, Russia, England, and Canada.

|

Please visit our sponsors:

|